BEYOND THE NUMBERS

"Tough-on-Crime" Bills in Louisiana and Kentucky Are Harmful, Costly Steps in the Wrong Direction; State Lawmakers Should Prioritize Policies That Will Actually Improve Public Safety

Lawmakers in both Kentucky and Louisiana have adopted antiquated "tough-on-crime" bills that will put more people behind bars and keep them there longer. These bills take an ineffective approach to crime that not only harms individuals and their families, but further expands bloated state corrections budgets. Lawmakers in both states and across the country should reject calls for more draconian criminal legal policies and instead look to invest in basic needs to help drive down crime and help everyone thrive.

The legislation that Louisiana and Kentucky lawmakers have enacted this year will lead to more incarceration and longer sentences:

- Lawmakers in Louisiana ultimately passed 20 bills in a ten-day special session in February. Among other things, these bills increased minimum sentences for carjacking, limited incarcerated people’s ability to reduce their sentences via good behavior, eliminated parole for most adults convicted of a crime, and will allow for 17-year-olds to be charged as adults for non-violent crimes.

- In Kentucky, lawmakers overrode the governor’s veto to pass HB 5, a sweeping bill that contains a range of policy changes including: expanding the definition of violent offenses, increasing penalties for a range of crimes, creating a “three strikes” law, legalizing the punishment of people experiencing homelessness simply because they can’t afford a place to live, and creating criminal penalties for parents of children involved in the youth justice system.

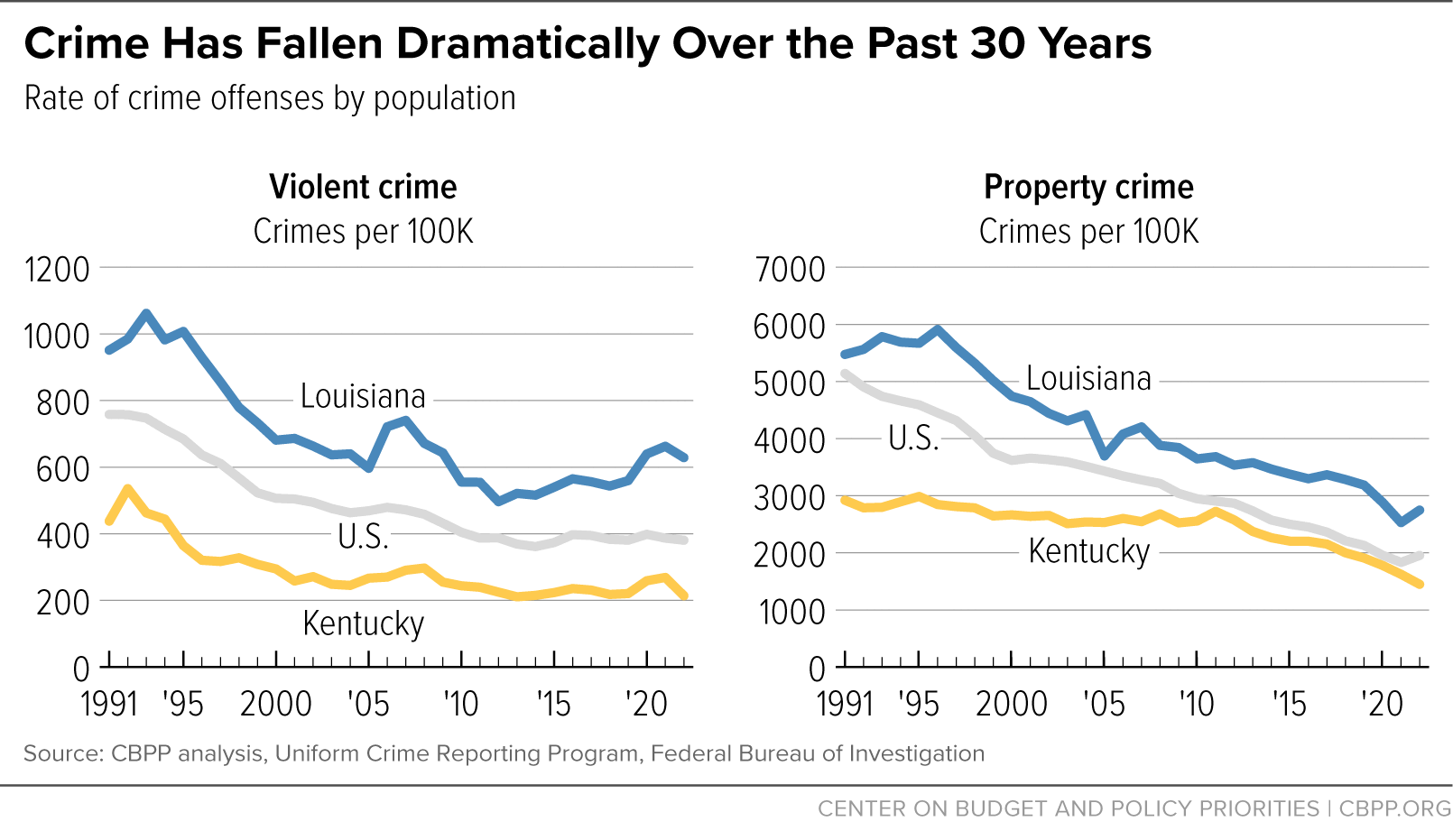

First, it’s important to challenge the underlying premise of these bills: rising crime. Reported crime — both violent and property — has been trending consistently downward for roughly three decades (see graphic). In 2020 and 2021, during the height of the pandemic, we did observe increases in certain types of crime — namely murder, aggravated assault, and car theft. These increases were relatively uniform across the country.

Louisiana and Kentucky have experienced similar trends. Between 1991 (the most recent peak of crime in the United States) and 2022, crime fell dramatically in both states. Louisiana experienced a 34 percent decline in violent crime and a 50 percent decline in property crime. Kentucky, which has typically had a crime rate well below the national average, saw a 50 percent reduction in both categories over the same time period. And while both states saw a jump in crime (particularly violent crime) in the first few years of the pandemic that mirrored national trends, rates remain historically low. In fact, preliminary data from the FBI show that nationally, crime declined nearly across the board in 2023— with the violent crime rate potentially falling to its lowest point in almost 60 years.

With these trends in mind, are “tough-on-crime” policies the solution to further drive down crime? No. Research emerging in recent decades has been clear that these policies have, at best, been marginally effective in reducing crime. It is the likelihood of being caught, not the severity of the penalty — especially when penalties are already harsh — that plays a larger role in a person’s decision to commit a crime. We also know that with incarceration rates remaining stubbornly high across the states, additional incarceration has even less of an effect on crime due to diminishing returns.

Ultimately, “tough-on-crime” policies can make life worse for many people. These policies can be deeply harmful to the individuals who are locked up, to their partners, and to children — disproportionately harming Black communities and other communities of color due to systemic biases in policing and unjust treatment in the criminal legal system. Instead, lawmakers should embrace alternatives that help improve safety while also improving outcomes for those at risk of becoming ensnared in the criminal legal system:

- For kids, there are a range of community-based alternatives with strong empirical evidence for reducing offenses by at-risk youth.

- Research has also indicated that expanding access to Medicaid, mental health services, and substance use disorder treatment programs can reduce both violent and property crime.

- Higher levels of educational attainment have been linked with reductions in violent crime, and increasing access to education and work programs for people who are incarcerated can lower the chance of recidivism.

- Increases in income and improved access to economic security programs can also help reduce property crime.

Finally, lawmakers must understand that the “tough-on-crime” approach is costly. In fiscal year 2022, state general fund spending on corrections was $55 billion nationwide. For most states, corrections spending is the fourth-largest general fund expenditure, behind K-12 schools, higher education spending, and Medicaid. In the same year, eight states spent at least 8 percent of their general fund dollars on prisons, and four states — Alaska, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Vermont — spent more general fund dollars on corrections than they did funding public colleges and universities. As more people are sent to prison and sentences lengthen, the number of people behind bars will increase — further pushing up costs and potentially crowding out spending on other important budget priorities.

Fiscal estimates on the bills in Louisiana and Kentucky back up these cost concerns. Fifteen of the 20 bills passed in Louisiana are estimated to increase state spending. Budget analysts were unable to calculate the full impact of these policy changes, but for the bills they were able to analyze, conservative estimates pegged the annual costs at a minimum of $30 million a year — with some forecasts going as high as $250 million annually. Kentucky’s HB 5 will also be expensive. Researchers estimated that just a few sections of the 78-page bill could cost the state $1 billion over the next decade.

As prison populations increase, and more capacity is built to house people who are incarcerated, costs will be very difficult to reduce in the long term. To see substantial savings, policymakers will need to reduce prison populations enough to close whole facilities and reduce staffing. Even in places where prison populations have fallen modestly, rising employee costs and the cost of health care have kept prison spending high.

The best course of action today is to avoid these costs altogether by refusing calls for misguided “tough-on-crime” policies and to prioritize proven alternatives that will improve public safety.