BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Research: Changes in Safety Net in Recent Decades Heavily Favored Working Families, Weakened Supports for Out-of-Work Families

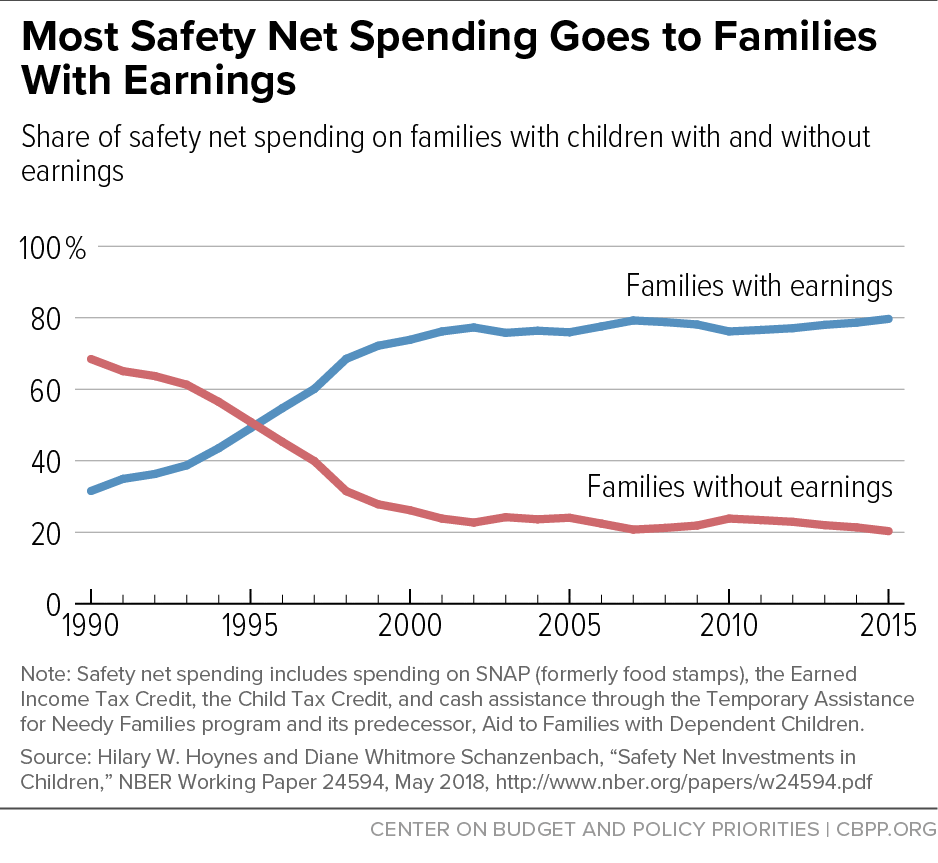

With the House set to consider extensive changes in SNAP (formerly food stamps) in the farm bill this week, leading researchers Hilary Hoynes and Diane Schanzenbach have found that over the past 25 years, the safety net has become far more targeted to working families and families with incomes somewhat above the poverty line, while supports for poor families that do not have earnings have declined (see chart for share of spending).

Hoynes and Schanzenbach’s findings provide a sharp contrast to rhetoric about the House farm bill’s SNAP proposals that implies that safety net programs are now overly generous to families in which the parent isn’t employed and don’t sufficiently emphasize work. The findings also suggest that taking SNAP away from needy families with children when their parents can’t work or participate in work programs could adversely affect the children for years to come.

Hoynes and Schanzenbach find that:

Virtually all of the increased spending on the safety net for children since 1990 has gone to families with earnings. In real terms, spending on families without earnings has fallen from $45 billion in 1990 to $33 billion in 2015. The share of total spending [on these safety net programs] going to families without earnings has fallen even more — from almost 70 percent of [such] spending in 1990 to 20 percent in 2015.

These figures are for total spending on SNAP, the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, and cash assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program and its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children. The same pattern holds if Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, and public housing are included, Hoynes and Schanzenbach note.

These trends also hold when accounting for the rise in the share of children with working parents; per-child spending rose substantially for children in families with earnings, while it fell somewhat for those without working parents.

On a related matter, the share of safety net spending going to families with incomes below the poverty line fell from about 87 percent of such spending in 1990 to 56 percent in 2015, while poverty didn’t fall nearly as much, the study found.

As key drivers of these trends, the authors cite both the expansion of tax credits for working families and the sharp decline in cash assistance, which was previously available to a substantially larger share of poor families and families without earnings. As our own research shows, in the mid-1990s, for every 100 poor families with children, 68 received cash assistance. Today, only 23 do.

These findings are particularly relevant to the current debate over SNAP. Unlike some other parts of the safety net, SNAP has become more effective at serving families with earnings while remaining effective at protecting children from severe poverty. As cash assistance has become far less available to very poor families with children, SNAP has partially filled the gap. SNAP has also become a much more effective work support, so when poor parents work in low-wage jobs, they can receive SNAP to supplement their low earnings.

Indeed, SNAP now reaches a substantially larger share of struggling working families than it used to. The share of eligible low-income individuals in working families that participate in SNAP has risen over the past 15 years from 43 percent of such families in 2002 to 72 percent in 2015.

Hoynes and Schanzenbach’s findings also suggest that harsh work requirements that would take SNAP away from needy families with children when their parents can’t work or participate in work programs could have adverse long-term effects on the children. The researchers point to important findings showing that disadvantaged young children who had access to SNAP (then called food stamps) when the program rolled out in the 1960s and 1970s were less likely to develop health conditions such as metabolic syndrome as they grew up, and were likelier to graduate from high school, than comparable poor children who didn’t have access to SNAP. Other recent research has found that SNAP reduces food insecurity (the lack of access to sufficient food due to the lack of resources), which can harm children’s development.

Hoynes and Schanzenbach’s study shows that SNAP is an important support for both low-income families that have employment and families that do not. Cutting food assistance for parents who can’t secure employment or can’t work would leave poor children with fewer resources and could have harmful, enduring impacts on them.