BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Two things largely lost in coverage of the latest inflation data undercut opposition to Build Back Better measures based on inflation concerns. First, contrary to perceptions that inflation is getting progressively worse month after month, the monthly increase in the consumer price index (CPI) slowed in the last part of 2021, and most analysts predict that inflation will moderate this year, though not necessarily early in the year. Second, while the pandemic has induced a shift toward purchases of goods rather than services, total consumer spending is roughly tracking its pre-pandemic trend, which counters assertions that aggregate spending is overly stimulated and we can’t afford further relief legislation — no matter its merits and design — out of concern that it will generate excessive consumer spending.

Let’s examine these points in turn.

The 7.0 percent increase in the CPI from December 2020 to December 2021 got the headlines last week, but the latest Labor Department data also show that the CPI rose 0.5 percent from November to December — much less than the 0.8 percent monthly increase in November and the 0.9 percent monthly increase in October. To be sure, this is only a short trend in a volatile measure. But it rebuts the notion that inflation is worsening month after month and supports the view of most analysts that inflation will come down this year — although there is considerable uncertainty about how much and how fast.

For example, projections from the individual Federal Reserve governors and Federal Reserve bank presidents for the change in the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index between the fourth quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter of 2022 ranged from 2 percent to 3.2 percent, with a median of 2.6 percent. (The PCE tends to grow a few tenths of a point slower than the CPI.)

One source of uncertainty is the trajectory of the pandemic itself. High levels of infections in the U.S. but also abroad can worsen supply problems if factories and delivery systems lose capacity because large numbers of staff are unable to work.

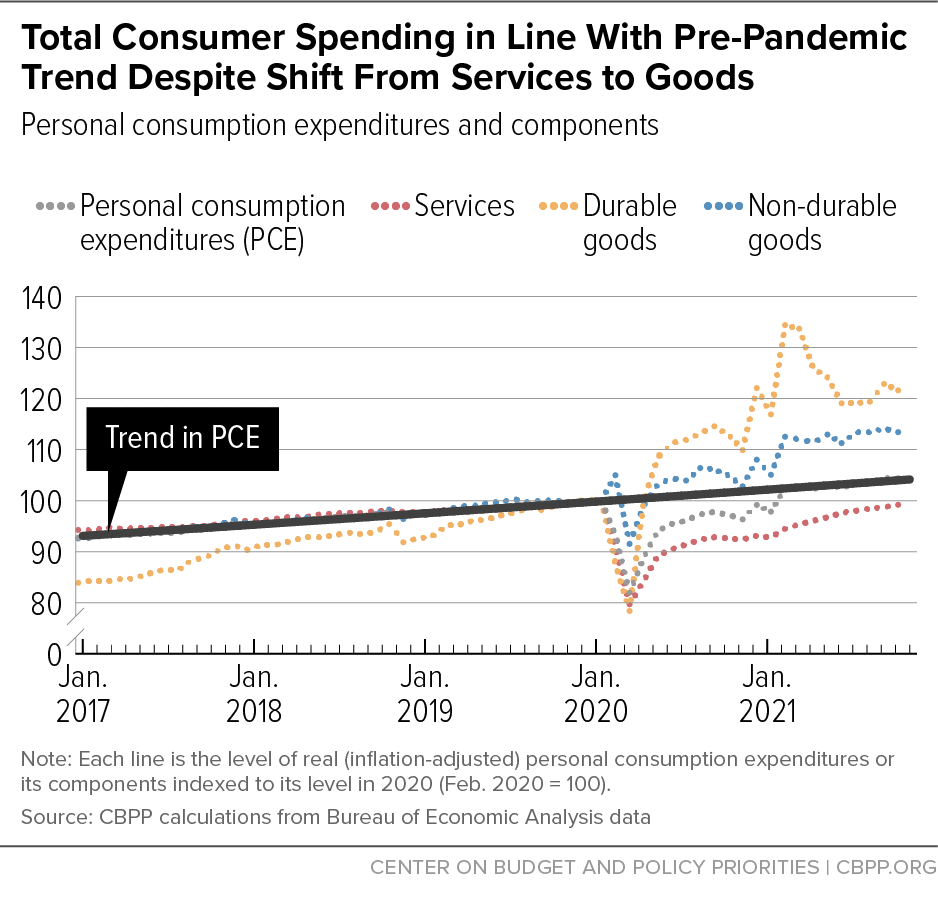

As for the cause of recent inflation, some assert that it’s entirely due to rapidly rising consumer expenditures fueled by the federal programs that relieved hardship in the pandemic and supported the economic recovery. Federal support for struggling families and unemployed workers did cushion the substantial decline in household income that otherwise would have occurred and supported spending that promoted a strong partial economic recovery in the second quarter of 2020. Relief bills enacted in December 2020 and March 2021 also boosted a flagging recovery and supported stronger growth. But total consumer spending, rather than surging above its pre-pandemic trend, has roughly tracked that trend lately, as the graphic shows.

The pandemic induced a dramatic shift in the components of consumer spending, away from services and toward goods. Goods purchases grew much more rapidly than services coming out of the recession in 2020 and surged again in the spring of 2021. Before the pandemic, goods accounted for about 35 percent of PCE but rose to 42 percent in March and April 2021, when inflation began increasing, and has remained about 40 percent since. Since April, rising goods prices have been responsible for over three-fifths of the increase in the CPI, up from less than half early in 2021.

The shift in consumption from services to goods, together with bottlenecks in the supply of goods, contributed greatly to large supply-and-demand imbalances, which have given rise to inflation. The pandemic economy has been like no other, with fluctuations in the demand and supply of goods, services, and labor. Focusing strictly on the demand created by government programs is too simplistic because it ignores the importance of supply constraints — often stemming from the impact of the health crisis itself, which resulted in, for example, reduced production of some key goods or an inability to ramp up production to meet demand — in creating shortages that lead to price increases.

Finally, unlike earlier stimulus and relief measures, which added substantially to near-term budget deficits and aggregate demand for goods and services, Build Back Better consists primarily of long-term investments paired with offsets that would raise revenue over time. While its Child Tax Credit expansion would increase consumer demand in 2022, the impact would be dwarfed by the negative fiscal drag from the expiration of earlier stimulus measures.

None of this is to deny that current inflation is high and will not come down as quickly as many expected when it first emerged last year. But the Federal Reserve is responsible for addressing unwanted inflation. It has clearly indicated its intention to fight inflation, and it has the tools to do so while remaining attentive to its dual mandate from Congress to promote both stable prices and maximum employment.

The President and Congress should get back to the negotiating table and agree on an economic package to help families meet everyday challenges and strengthen our economy.