BEYOND THE NUMBERS

In the 21 years since welfare reform in 1996 created it, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program has failed in its two main purposes: to provide a safety net and to adequately support parents’ transition to work. TANF’s reach has shrunk, benefits to recipients have lost purchasing power, and states spend little to improve parents’ employability, as we illustrate in our updated chart book. Its performance shows why it’s not a model for improving other low-income programs.

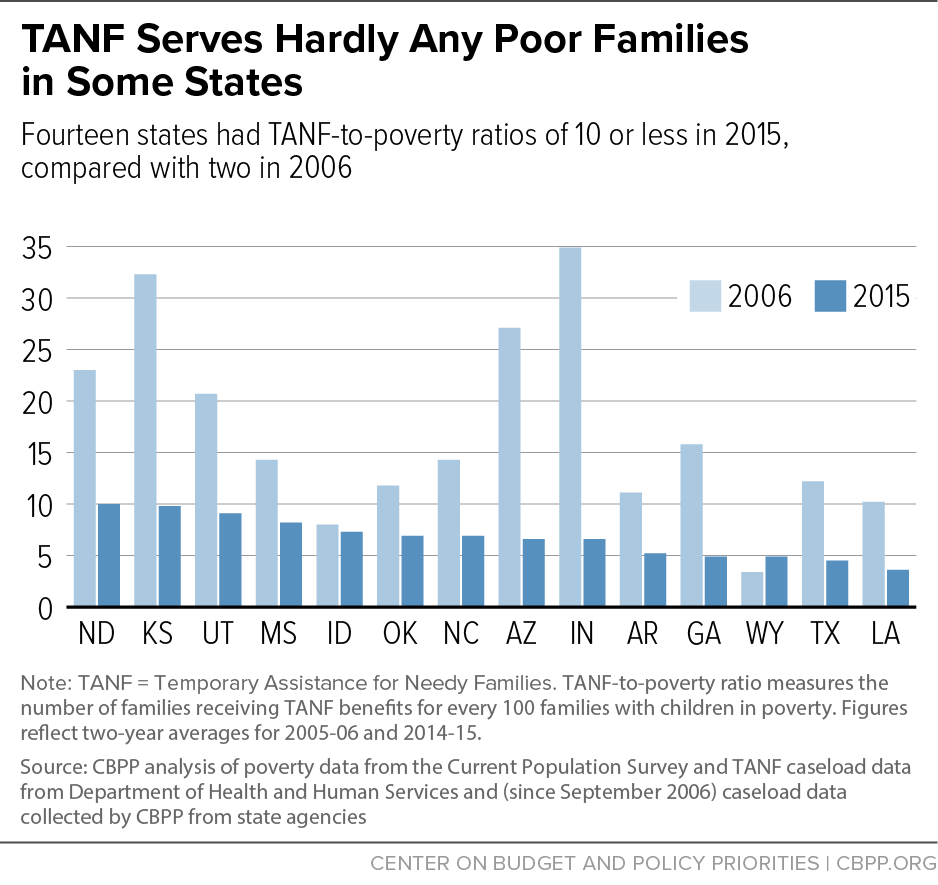

Under the last year of TANF’s predecessor, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, nationally, 68 families received assistance for every 100 families in poverty; that number has since fallen to just 23 families receiving assistance under TANF for every 100 families in poverty. Even more troubling has been the trend of states with such ratios (the TANF-to-poverty ratio) of 10 or less. In 2006, only two states, Idaho and Wyoming, had such low ratios. In 2015, 14 states did (see chart). The number of states in this category will continue to grow as TANF fails to adequately respond to need.

For those who do receive TANF assistance, the cash benefit has continued to erode in value. Since 1996, benefits have fallen by 20 percent or more in 35 states plus Washington, D.C., after adjusting for inflation. Sixteen states had the same nominal benefit levels in July 2017 as in 1996, meaning that benefits have fallen in inflation-adjusted terms by more than 35 percent. In five states (Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Oklahoma, and Washington), TANF benefits are below their nominal 1996 levels. After adjusting for inflation, benefits in Arizona and Hawaii are more than 40 percent below their 1996 levels.

This makes it hard for families who turn to TANF for assistance to meet their basic needs like affording decent housing. No state’s benefit covers the estimated cost of a modest two-bedroom apartment and utilities. TANF families without housing assistance have high rates of housing instability, which leads to doubling up with friends or relatives, living in substandard conditions, frequent moves, eviction, and/or homelessness.

Proponents of a flexible block grant believed that when families were required to work, fewer would need cash assistance and states would reinvest the savings into services that would help recipients find jobs and cover the costs of child care and work supports like transportation. That’s not what happened.

In TANF’s early years, states increased spending on work programs modestly, but they didn’t maintain those levels. States spent only 7 percent of their state and federal TANF funds on work activities in 2015, and 3 percent on work supports and supportive services like transportation.

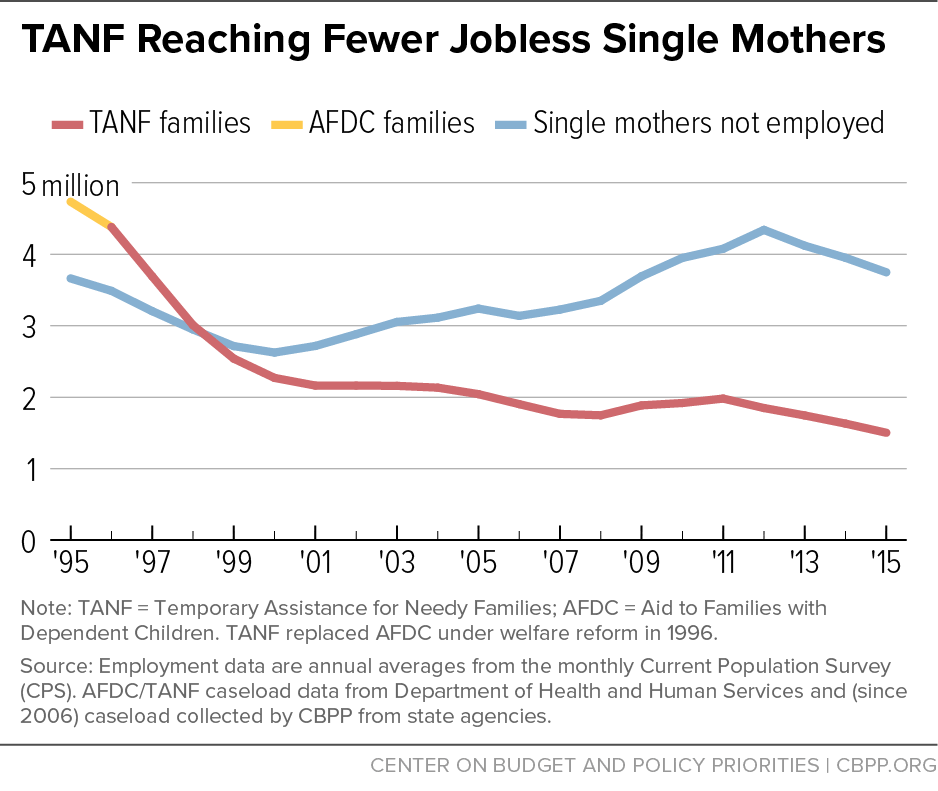

States invest little in helping parents find and keep jobs, but not because the need isn’t there. TANF is failing to reach not only families in poverty, but also single mothers who aren’t working. In 2015, the number of unemployed single mothers was about 2.5 times the number of families receiving TANF in an average month. This gap was substantial even before the Great Recession, but it widened substantially during and just after the recession (see second chart).

Policymakers who want to help low-income families and encourage work shouldn’t lift TANF up as a model for other programs. Instead, they should protect programs like SNAP and Medicaid, which provide critical supports for all working families and individuals who qualify.