- Home

- Food Assistance

- State WIC Agencies Continue To Use Feder...

State WIC Agencies Continue to Use Federal Flexibility to Streamline Enrollment

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care and social services to pregnant and postpartum people with low income, infants, and children under age 5. Despite the well-documented benefits associated with WIC participation,[1] in recent years more than 40 percent of eligible people have not been enrolled, especially pregnant individuals and children aged 1 through 4.[2] To reach more eligible families with low income, state and local WIC agencies have adjusted their policies and practices to remove barriers to enrollment, efforts that were accelerated under COVID-19-related waivers of certain program rules.[3]

Understanding which policies states have implemented can help federal policymakers update those program rules — legislatively, when WIC is reauthorized, or administratively — and state program administrators identify opportunities to simplify WIC enrollment procedures after the COVID-related waivers expire.[4] WIC state agencies can use this compilation of selected state WIC certification policies gathered from state program administrators in July and August 2021 to identify policies they might wish to adopt and connect with states that have adopted them.[5]

More widespread adoption of policies that allow eligible individuals to receive benefits easily and promptly could increase WIC enrollment and improve health outcomes. Such policies include:

- determining income and/or residence eligibility in advance to reduce the duration of the certification appointment and decrease the number of documents that applicants must provide during the appointment;

- using presumptive eligibility to begin providing food benefits as soon as pregnant applicants are determined to be income eligible;

- allowing temporary 30-day certifications to give applicants more time to provide eligibility documents without delaying food benefits; and

- eliminating the requirement that households without any income provide a third-party statement, which can prevent or delay vulnerable families from accessing nutrition assistance during periods of prenatal, infant, and child development.

Assessing Your WIC Certification Practices

A toolkit to help WIC agencies modernize and streamline the certification process is available at www.cbpp.org/wiccertificationtoolkit. The toolkit includes descriptions of practices for facilitating WIC enrollment and simplifying eligibility determinations, along with examples from WIC state and local agencies and additional resources.

In This Report: Updated Certification Policies and Practices

Eligibility for WIC benefits is assessed when applicants first apply and periodically thereafter. The program serves certain categories of applicants — infants and children up to age 5, pregnant individuals, and postpartum individuals for up to one year. Additional WIC eligibility criteria include income, residence, and nutritional risk. Applicants are also required to provide identification. Eligible applicants are certified for up to one year. While WIC programs operate under certain federal eligibility rules and policies, state and local WIC agencies have considerable flexibility to determine how they certify new applicants and recertify participants. State WIC agencies set policies and procedures for certifying eligibility, and local agencies or clinics implement these within the context of their staffing patterns and facilities. As a result, WIC agencies employ a wide range of certification options and a variety of processes.

During 2016, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) collected information about selected certification policies and practices for a report published in January 2017.[6] Since then, many state and local WIC agencies have changed their certification processes. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic required agencies to adopt new ways of certifying and serving participants. Increased use of technology and experience with remote appointments has increased flexibility and simplified certification processes while inspiring creative ways of gathering information.

As a result, many promising practices are emerging. Practices such as online applications and electronic referrals from health care providers streamline WIC enrollment, which helps both participants and staff. Increased coordination with health care providers reduces the need for families to provide duplicative information and for WIC staff to collect measurements and bloodwork, which contributes to streamlining the certification process and enhancing continuity of care.

To document some of the changes, in July 2021 and again in July 2022 CBPP asked the 50 geographic WIC state agencies to update the information about certification policies and practices published in the previous report and to provide responses to questions about additional items. The District of Columbia was also asked to provide the information in 2022. While other U.S. Territories and tribal organizations serve as state agencies operating the WIC program, their policies are not included in this report because the geographic state agencies served the vast majority (97 percent) of WIC participants in fiscal year 2021.

The policies described in this report are allowed under the regular program rules, will remain available to states after the COVID-related waivers expire, and can be adopted by states by amending their state plan, revising their policy manual, or both. Nearly all states responded (47 of 50 in 2021 and 48 of 51 in 2022) and the information they provided is summarized in four sections, each with a table of policies and practices across the state agencies. The tables show the range of certification processes states have adopted and can be used as resources for federal stakeholders to understand their use and for state program administrators to connect with their peers to learn about different approaches.

Adjunctive Eligibility Simplifies Enrollment

To help ensure that low-income families with young children receive the full array of benefits and supports for which they are eligible, and to avoid duplicative administrative work, policymakers have streamlined enrollment across benefit programs through a policy known as adjunctive eligibility. Under federal law, applicants enrolled in Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)[7] meet WIC’s income requirement.[8]

This long-standing policy simplifies the eligibility determination for about 3 in 4 applicants.[9] While nearly all states accept an applicant’s paper documentation of Medicaid, SNAP, or TANF participation, such as an eligibility determination letter, most also use a variety of other options to check for an applicant’s participation. Some WIC agencies have access to online portals or data or automated phone systems set up by the other programs, while several have integrated a process to check for adjunctive eligibility into the WIC information system.

Several state WIC agencies accept documentation of enrollment in Medicaid, SNAP, or TANF to document both income and residence if that program checks residence within the state as part of its eligibility process. Enrollment in these programs is also used to document identification in some states, which maximizes the benefit of checking for adjunctive eligibility. Use of one source, whether through adjunctive eligibility or another form of documentation, to document multiple eligibility factors makes the process easier for both participants and staff.

Table 1 shows how state agencies direct local staff to check for adjunctive eligibility. It also includes state policies for using adjunctive eligibility documentation to document residence and/or identity in addition to income.

| TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjunctive Eligibility Documentation | ||||||

| How does the state agency direct local agencies/clinics to check adjunctive eligibility? | ||||||

| Approval notice from agency that administers Medicaid, SNAP, TANF, and/or other applicable program1 | Call to automated phone system to check Medicaid, SNAP, TANF, and/or other applicable program1 | Online access to Medicaid portal/data | Online access to SNAP and/or TANF program portal(s)/data | Interface built into WIC eligibility system that checks Medicaid, SNAP, and/or TANF eligibility |

Does the state allow documentation of adjunctive eligibility to document residence and/or identity in addition to income? Legend:

|

|

| Alabama | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | RES, ID2 |

| Alaska | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| Arizona | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Arkansas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| California | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | RES, ID |

| Colorado | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| Connecticut | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Delaware | No | No | No | No | Yes | RES, ID |

| District of Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Florida | Yes | -- | Yes | -- | -- | No |

| Georgia | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | RES |

| Hawai’I | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | In process | In process |

| Idaho | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Illinois | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | RES |

| Indiana | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Iowa | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Kansas | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Kentucky | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | In process | RES, ID |

| Louisiana | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| Maine | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Maryland | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | ID |

| Massachusetts | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Michigan | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | RES, ID |

| Minnesota | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| Mississippi | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Missouri | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | RES, ID |

| Montana | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| Nebraska | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | ID |

| Nevada | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| New Hampshire | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Res |

| New Jersey | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | ID |

| New Mexico | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | RES, ID |

| New York | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| North Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | RES, ID |

| North Dakota | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES |

| Ohio | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ID |

| Oklahoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Oregon | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| Rhode Island | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | RES, ID |

| South Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | RES, ID |

| South Dakota | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | RES, ID |

| Tennessee3 | -- | Yes | Yes | Yes | -- | -- |

| Texas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | In process | RES, ID |

| Vermont | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Virginia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | -- | RES, ID |

| Washington | Yes | Yes | No | Participant access | Yes (MED) | RES, ID |

| West Virginia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | RES, ID |

| Wisconsin | Yes | Yes | Yes | In process | No | RES |

| Wyoming | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

1 Under federal rules, state agencies may accept documentation of the applicant’s participation in state-administered programs that routinely require documentation of income, provided that those programs have income eligibility limits at or below WIC’s. State agencies include other applicable programs in their annual WIC state plan. See 7 C.F.R. §246.7(d)(2)(vi)(B).

2 Alabama WIC permits adjunctive eligibility documentation for up to two of three requirements (income, residence, identity).

3 Responses for Tennessee are from 2016. These states did not respond to a request to update their entries in 2022.

Source: Information gathered by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities from state policy documents and directly from state WIC staff in July and August 2022

States Have Broadened Options for Applicants to Document Eligibility

Federal rules allow WIC staff to accept documents that are shown in electronic form during in-person appointments or transmitted electronically. States vary with regard to whether they address electronic documents in their policy manuals or train staff to routinely ask for them. But in recent years, state agencies have been updating policies on allowable eligibility documents to include electronic options, such as scanned documents or photos of documents.

Prior to the pandemic, it was uncommon for WIC agencies to offer a mechanism to transmit documents electronically. But all states established such mechanisms as they transitioned to conducting certification appointments by telephone or video to protect participants and WIC staff after the onset of COVID-19. Now state policies allow for a range of methods for participants to rely on electronic documents before, during, or after certification appointments. Applicants (both individuals applying for the first time and those being recertified) can show documents on their telephones during in-person or video appointments, or they can send a photo or screenshot of a document via text message, email, or fax. Several state or local agencies have set up document uploading capability as part of an online application or within their WIC portals, while others offer standalone tools for uploading documents.

In a survey of more than 26,000 WIC participants conducted by 12 state agencies during March and April 2021, nearly 60 percent of participants reported emailing documents with personal information to WIC and 36 percent sent their documents using text messaging.[10] In the five state agencies that make a portal or online resource available to participants, nearly one-quarter of participants reported using that method to upload documents. When asked to rate their comfort (on a scale of 1 = uncomfortable to 4 = comfortable) with the methods they had used to share their personal information with WIC, most respondents (92.2 percent) were either comfortable or somewhat comfortable. Nonetheless, as state and local agencies determine which document transmission mechanisms to offer on an ongoing basis, it is important to use methods that protect the confidentiality of the information provided without sacrificing ease of use.[11]

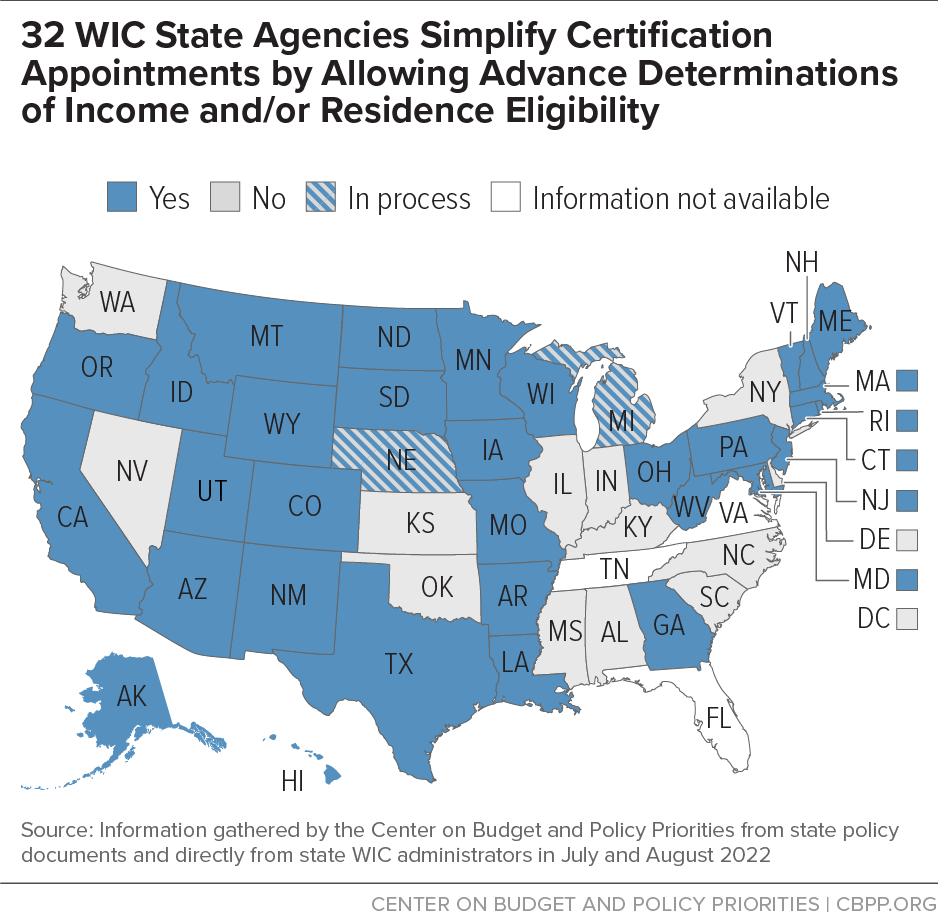

Some state agencies permit local staff to begin the eligibility process before the certification appointment by checking for adjunctive eligibility or viewing documents submitted by new applicants or individuals being recertified. The period before the appointment ranges from the same day to up to 30 days.[12] This practice reduces the duration of the appointment and can also decrease the number of documents that applicants must bring with them. Despite the benefits to both applicants and staff, at least 21 states have not yet adopted this practice but could implement it to simplify enrollment. (See Figure 1.)

By maximizing the use of electronic documents and adjunctive eligibility, agencies can reduce the number of applicants with incomplete documentation. When documentation is missing, however, most state agencies permit a temporary 30-day certification to give the applicant more time to provide eligibility documents without delaying food benefits. The applicant must provide appropriate documentation within 30 days to continue receiving benefits. Flexible, electronic options for submitting the information without having to return to the clinic are important to help ensure participants with temporary certifications become fully certified.

Some state and local agencies monitor the number of temporary certifications as well as the number of these that become full certifications. If many participants are certified for only 30 days, this may indicate a need for staff training on maximizing the use of electronic documents. For example, by training staff to view and receive documents electronically, Maricopa County, Arizona lowered the share of certifications that were temporary because clients had not provided all required documents from 26 percent to 2 percent.[13] A high rate of temporary certifications that do not become full certifications may warrant more follow-up assistance to ensure that eligible and interested families are able to submit the documentation necessary to continue receiving benefits.[14]

Table 2 compiles state policies on use of electronic documents as well as policies on checking eligibility prior to certification appointments and on temporary certifications.

| TABLE 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected State Policies on Electronic Eligibility Documentation, Checking Eligibility Prior to Certification Appointments, and Temporary Certifications | |||||||||||

|

Legend:

|

|||||||||||

| Does the state provide direction regarding whether a local agency/clinic may accept electronic documents? | If yes, what options for sharing electronic documents are included? | Does the state allow for determining income and/or residence eligibility in advance of the certification appointment? | If yes, how far in advance? | Does the state allow temporary certifications of up to 30 days for applicants who do not have income, identity, or residence documentation? | If yes, which documents can be missing? | ||||||

| Alabama | Yes | EML | No | No | |||||||

| Alaska | Yes | PHN, EML, TXT, FAX | Yes | NS | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Arizona | Yes | UPL, EML | Yes | NS | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Arkansas | Yes | PHN, EML, TXT, OTH | Yes | OTH | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| California | Yes | EML, PHN, VID, UPL, FAX | Yes | NS | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Colorado | Yes | FAX, EML | Yes | ≤1 week | Yes | INC, RES | |||||

| Connecticut | Yes | NS | Yes | SMD | Yes | INC, RES | |||||

| Delaware | Yes | EML, MIS | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| District of Columbia | No | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||||

| Florida | Yes | EML, FAX | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||||

| Georgia | Yes | PHN, EML, UPL | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Hawai’i | Yes | PHN, TXT, EML, FAX | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Idaho | Yes | PHN, UPL | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Illinois | Yes | PHN, VID, EML, TXT | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| Indiana | Yes | PHN, EML, FAX | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| Iowa | Yes | PHN, VID, TXT, EML, FAX, UPL | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES | |||||

| Kansas1 | Yes | PHN, EML, TXT, FAX | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| Kentucky | Yes | PHN, EML, FAX, OTH | No | Yes 2 | INC, RES, ID2 | ||||||

| Louisiana | Yes | PHN, EML, FAX, UPL | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Maine | Yes | PHN, VID, EML, TXT, FAX, UPL | Yes | ≤1 week | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Maryland | Yes | PHN, VID, TXT, EML, FAX, UPL | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Massachusetts | Yes | PHN, EML, TXT, FAX | Yes | ≤30 days | No | ||||||

| Michigan | Yes | PHN, VID, EML, TXT, FAX | In process | In process | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Minnesota | Yes | NS | Yes | ≤21 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Mississippi1 | No | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||||

| Missouri | Yes | EML, FAX, TXT, PHN, UPL | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Montana | Yes | NS | Yes | ≤1 week | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Nebraska | Yes | EML VID, TXT, UPL | In process | No | |||||||

| Nevada | Yes | EML, TXT | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| New Hampshire | Yes | EML, TXT, FAX | Yes | Same month as certification | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| New Jersey | Yes | EML, TXT, PHN, OTH | Yes | ≤30 days | No | ||||||

| New Mexico | Yes | EML, UPL, FAX | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| New York | Yes | PHN, TXT, EML, VID, FAX | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| North Carolina | Yes | EML, TXT, PHN | No | No | |||||||

| North Dakota | Yes | EML, PHN, TXT, FAX | Yes | Yes | INC, RES | ||||||

| Ohio | No | Yes | NS | No | |||||||

| Oklahoma | Yes | EML, TXT, PHN, FAX, UPL | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| Oregon | Yes | VID, EML, TXT, UPL | Yes | ≤5 business days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Pennsylvania | Yes | NS | Yes | ≤1 week | No | ||||||

| Rhode Island | Yes | EML, TXT, FAX | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| South Carolina | Yes | PHN, TXT, EML, FAX | No | Yes | INC | ||||||

| South Dakota | Yes | PHN, TXT, EML, FAX | Yes | ≤72 hours | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Tennessee1 | No | -- | No | ||||||||

| Texas | Yes | PHN, VID, EML, FAX, UPL | Yes | NS | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Utah | Yes | PHN, VID, EML, TXT | Yes | ≤1 week | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Vermont | Yes | EML, PHN, FAX | Yes | 1-2 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Virginia | No | -- | No | -- | |||||||

| Washington | Yes | VID, EML, TXT | No | Yes | INC, RES, ID | ||||||

| West Virginia | Yes | PHN, EML, TXT, FAX | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Wisconsin | Yes | PHN, VID, EML, TXT, FAX, UPL, OTH | Yes | ≤10 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

| Wyoming | Yes | EML, FAX | Yes | ≤30 days | Yes | INC, RES, ID | |||||

1 Responses for Tennessee are from 2016 and responses for Kansas and Mississippi are from 2021. These states did not respond to a request to update their entries in 2022.

2 In Kentucky, 30-day temporary certifications are permitted for hospital certifications only.

Source: Information gathered by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities from state policy documents and directly from state WIC staff in July and August 2022

States Can Adopt Other Policies to Streamline Certification

There are other ways state WIC agencies can adjust their policies and local WIC agencies can adjust their practices to make the certification process easier to navigate and less burdensome for both participants and staff. This section explains selected policies that could further those goals. States that wish to comprehensively assess their certification process to identify opportunities for modernization and streamlining can use CBPP’s toolkit, “Assessing Your WIC Certification Practices,” which offers approaches, examples, and resources.[15]

Exceptions to Attending Appointments in Person

Federal law permits state WIC agencies to exempt certain individuals from the requirement that applicants be physically present at certification appointments: infants or children receiving ongoing health care (after the initial certification); infants or children with working parents (after the initial certification and with a limit on how much time can elapse between in-person appointments); and newborn infants under 8 weeks old. For adults, exemptions from the physical presence requirement are limited to individuals with disabilities. Under waivers approved by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) during the pandemic, state agencies made remote appointments available to all applicants and participants to protect the health of families and WIC staff. Participants were offered telephone and video certification appointments and options for providing eligibility information without visiting a WIC office. In a survey of 26,000 participants across 12 states conducted during 2021, participants reported that the quality of services they received during the pandemic was the same (49.7 percent) or better (37.7 percent) than before the pandemic. Nearly half (45.4 percent) responded that they would prefer to continue remote WIC appointments when the pandemic ends.16 Once the waivers expire, offering telephone or video appointments for certification when a physical presence exemption applies, or for infant or child mid-certification health and nutrition assessments, can make it easier for parents and caretakers to schedule and keep appointments.

When infants or children are not present, it is important to collaborate with health care providers to obtain measurements and blood test results to inform the nutrition assessment. While most state agencies received COVID waivers for obtaining measurements and bloodwork, many state and local agencies coordinated with health care providers to get this information to inform nutrition assessments during certification appointments conducted by phone or video. WIC participants appreciated this change. In a multistate survey of WIC participants, 60 percent of the respondents selected using measurements and blood tests from doctors’ visits as an advantage of WIC services during the pandemic.[16] In clinics that have resumed offering in-person services, some agencies also allow “drop-in” visits for parents to bring the infant or child to the WIC site briefly for measurements and blood tests whenever it is convenient, before or after a certification appointment conducted remotely.

Expedited Enrollment for Pregnant Individuals

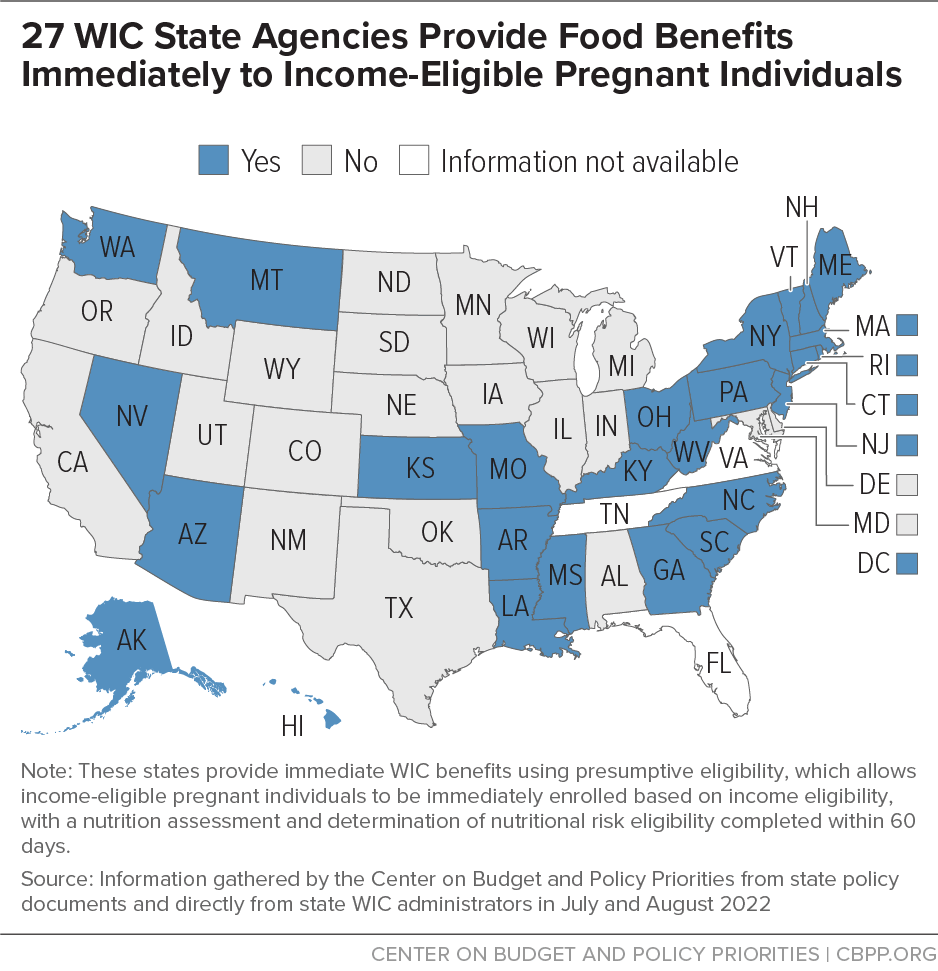

Federal WIC rules also allow for pregnant individuals who meet the income standards to be immediately enrolled as presumptively eligible based on income eligibility, with a nutrition assessment and determination of nutritional risk eligibility completed within 60 days. Some state WIC agencies use this option and include presumptive eligibility for prenatal applicants with nutrition assessment within 60 days or, in a few cases, 30 days.

As Figure 2 illustrates, about half the states (27) have adopted a two-step process that may make it easier to enroll pregnant individuals as soon as they contact WIC to apply. This approach can make it easier to deliver WIC’s food benefits to pregnant individuals earlier in pregnancy. For example, when a parent of a child participating in WIC shares that they are pregnant during an appointment for their child, they could be enrolled right away (assuming the family is already income-eligible) and begin to receive food benefits immediately. The nutrition assessment and risk determination could be scheduled one or two months later. For a prenatal applicant who does not have a child participating in WIC, a two-step process may be less overwhelming than a single appointment. The first contact could focus on collecting demographic information, confirming income eligibility, making referrals for prenatal care or other support, assigning a food package, and providing education on WIC foods and how to shop for them. The second contact could focus on a nutrition assessment, nutrition and breastfeeding education, and the participant’s questions about shopping or using WIC foods. If the second contact is scheduled after a prenatal health care appointment, measurements and blood test results may be available for use in the nutrition assessment.

By enrolling pregnant individuals and providing food assistance as soon as they are determined to be income eligible, WIC can reach them earlier in their pregnancy so they receive the maximum benefit from the program. Only about half (50.8 percent) of prenatal participants are enrolled in the first trimester of pregnancy.[17] Implementing presumptive eligibility might help increase this share.

More widespread adoption of this policy offers an opportunity to reach individuals with low income earlier in pregnancy, which may yield greater health and nutrition improvements.

Self-Declaration of Income

As permitted under federal law, nearly all state agencies allow applicants to self-declare their income when they are unable to provide documentation.[18] This flexibility accommodates vulnerable families, such as those who are experiencing homelessness or who have been affected by a natural disaster.

Families with no income are also likely to be experiencing substantial hardship. Under the federal rules, they are allowed to self-declare their income and state WIC agencies are not required to obtain a third-party statement verifying their income.[19] Instead, federal guidance suggests inquiring about their circumstances and how they obtain basic necessities such as food, shelter, medical care, and clothing in order to correctly apply program rules about household size and income, as well as providing important referrals for assistance.[20] As in other circumstances, WIC staff may require third-party verification if they determine it is necessary to confirm self-reported information, but third-party verification does not need to be obtained just because a household reports zero income.[21] Nonetheless, 12 state agencies require a third-party statement from all households that report not having income.

Having periods without any income is not unusual for poor households. In a typical month in 2019, 18 percent of households receiving SNAP benefits — over 3 million households — had zero gross income.[22] There are many situations in which a family can manage on a temporary basis without income. The family might be living in public or shared housing, getting food provisions at a food pantry, eating meals at a soup kitchen, or relying on other in-kind benefits.

Requiring such families to find an official or entity to document the absence of income creates a special burden for families who are likely to be extremely fragile or facing a crisis. As a result, such a requirement can prevent or delay vulnerable families from accessing nutrition assistance during periods of prenatal, infant, and child development when even short periods of food insecurity can have lasting consequences.[23] States can help deliver WIC’s essential foods promptly to families without income by utilizing the federal flexibility to eliminate the requirement to document lack of income.

Document Retention

State policies vary with regard to how local WIC staff are instructed to handle documents that are shared with them to demonstrate eligibility. For applicants who meet eligibility requirements, about half of state agencies do not have a document retention policy or they have a policy to return documents to applicants or discard them. State agency policies requiring documents to be retained most often specify income documents. With increased use of electronic documents, applicants will be providing fewer paper items and policies for handling documents with confidential information are likely to evolve. It will be increasingly important for state agencies to adopt clear policies for processes used to collect the documents and for storage or deletion after they are used to determine eligibility that balance protecting applicants’ privacy, reducing the duration of certification appointments, and using staff time efficiently.

Several state WIC agencies noted that they require copies of documents to be kept only for applicants found to be ineligible. This is likely a policy in other states since these documents are important for potential fair hearing requests.

Table 3 shows state agency policies related to income self-declaration, document retention, physical presence exemptions for infants and children, and presumptive eligibility for prenatal applicants.

| TABLE 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected State Policies on Income Self-Declaration, Retaining Eligibility Documents, Physical Presence Exemptions, and Prenatal Presumptive Eligibility | |||||||

| Does the state exempt infants/children of working parents from the physical presence at certification requirement? | Does the state allow for prenatal individuals to be certified as presumptively eligible for up to 60 days? | Does the state allow applicants to self-declare income (other than for temporary certifications)? | Does the state require a third-party statement for zero-income households? | Does the state provide direction about keeping copies of residence, identity, and/or income documents? |

If yes, what type of document is required?1 Legend:

|

||

| Alabama | No | No | Yes | No | No | ||

| Alaska | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | INC | |

| Arizona | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Arkansas | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | DIS | |

| California | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | ||

| Colorado | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Connecticut | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | DIS | |

| Delaware | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | INC | |

| District of Columbia | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Florida | No | -- | Yes | No | -- | -- | |

| Georgia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | INC, ETR | |

| Hawai’i | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | DIS | |

| Idaho | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | ||

| Illinois | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | OTH | |

| Indiana | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Iowa | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | OTH | |

| Kansas2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||

| Kentucky | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||

| Louisiana | No | Yes – for 30 days | Yes | Yes | Yes | DIS | |

| Maine | Yes | Yes – for 30 days | Yes | No | Yes | ELE | |

| Maryland | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | ETR | |

| Massachusetts | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ETR | |

| Michigan | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ELE | |

| Minnesota | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Mississippi2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | ETR | |

| Missouri | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||

| Montana | Yes | Yes – for 30 days | Yes | No | Yes | ELE | |

| Nebraska | No | No | No | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Nevada | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||

| New Hampshire | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||

| New Jersey | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | DIS | |

| New Mexico | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | ELE | |

| New York | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| North Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||

| North Dakota | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Ohio | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Oklahoma | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Oregon | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | ||

| Pennsylvania | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Rhode Island | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | -- | |

| South Carolina | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| South Dakota | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | INC, ELE | |

| Tennessee2 | No | -- | No | Yes | No | ||

| Texas | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | INC, ELE | |

| Utah | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Vermont | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Virginia | No | -- | Yes | Yes | Yes | INC, ELE | |

| Washington | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| West Virginia | No | Yes – for 30 days | Yes | No | No | ||

| Wisconsin | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

| Wyoming | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | DIS | |

1 Some state agencies require eligibility documents to be retained only when applicants are determined to be ineligible.

2 Responses for Tennessee are from 2016 and responses for Kansas and Mississippi are from 2021 These states did not respond to a request to update their entries in 2022.

Source: Information gathered by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities from state policy documents and directly from state WIC staff in July and August 2022

Nearly All States Have Shifted to Full-Year Certification Periods

Under federal law, state WIC agencies may establish certification periods of one year rather than six months for breastfeeding individuals, infants, and children aged 1 through 4. In 2016, all geographic state agencies reported they had adopted a full-year certification period for breastfeeding individuals and for infants enrolled prior to 6 months of age, and most reported having adopted it for children as well. As Table 4 shows, all states and the District of Columbia have a full-year certification for breastfeeding individuals and infants; only one state currently reports that it is not implementing this option for children.

| TABLE 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Year Certification Periods | |||

| Breastfeeding individuals | Infants under 6 months | Children (aged 1 through 4) | |

| Alabama | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Alaska | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Arizona | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Arkansas | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| California | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Colorado | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Connecticut | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Delaware | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| District of Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Florida | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Georgia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hawai’i | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Idaho | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Illinois | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Indiana | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Iowa | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kansas1 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kentucky | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Louisiana | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Maine | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Maryland | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Massachusetts | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Michigan | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Minnesota | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mississippi1 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Missouri | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Montana | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nebraska | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nevada | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New Hampshire | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New Jersey | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New Mexico | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| New York | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| North Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| North Dakota | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ohio | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Oklahoma | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Oregon | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rhode Island | Yes | Yes | No |

| South Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| South Dakota | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tennessee1 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Texas | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Utah | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vermont | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Virginia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Washington | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| West Virginia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wisconsin | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wyoming | Yes | Yes | Yes |

1 Responses for Tennessee are from 2016 and responses for Kansas and Mississippi are from 2021. These states did not respond to a request to update their entries in 2022.

Source: Information gathered by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities from state policy documents and directly from state WIC staff in July and August 2022

Conclusion

State and local WIC agencies have the flexibility under federal rules to adjust their policies and practices to remove barriers to enrollment, which can help them reach more eligible families with low income. The policies compiled here demonstrate that WIC administrators have made widespread use of these flexibilities. In addition, operations under COVID waivers have demonstrated how WIC can deliver important nutrition assistance and services in ways that are less burdensome to participants. As federal policymakers consider revisions to the law and rules that govern WIC, permanently adopting some of those temporary flexibilities that allow states to streamline and modernize the certification process could help more of the families with low income who are eligible for WIC get enrolled, especially earlier in pregnancy, and remain enrolled as infants become toddlers and preschoolers.

Even without federal changes, broader adoption of several of these policies — such as determining income and/or residence eligibility in advance of the certification appointment, allowing presumptive eligibility for prenatal individuals, allowing temporary 30-day certifications, and eliminating the requirement that zero-income households provide a third-party statement — could help states enroll more eligible families, putting children on a healthier course for life.

Modernizing and Streamlining WIC Eligibility Determination and Enrollment Processes

Other versions of this report

- Apr 1, 2022

End Notes

[1] For more information about the research evidence on WIC’s effectiveness, see Steven Carlson and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for More Than Four Decades,” CBPP, updated January 27, 2021, www.cbpp.org/wicworks; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Reviewing the Evidence for Maternal Health and WIC,” report to Congress, July 2021, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/reviewing-evidence-maternal-health-and-wic; and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, “Maternal and Childhood Outcomes Associated with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC),” research protocol, amended May 14, 2021, https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/outcomes-nutrition/protocol.

[2] Kelsey Gray et al., “National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2019 Final Report,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, February 2022, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICEligibles2019-Volume1.pdf.

[3] For example, participants are allowed to enroll or recertify without visiting a WIC clinic or providing measurements and bloodwork, and clinics are allowed to issue food benefits remotely. For a description of all the available waivers and which states adopted them, see the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “WIC COVID-19 Waivers,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/programs/fns-disaster-assistance/fns-responds-covid-19/wic-covid-19-waivers#:~:text=Remote%20Benefit%20Issuance%20%2D%20FNS%20is,and%20postpone%20certain%20medical%20tests.

[4] The COVID-related waivers will expire 90 days after the public health emergency ends. Dana Rasmussen, “WIC Policy Memorandum #2021-10: Updated Expiration Schedule for Existing FNS-Approved WIC COVID-19 Waivers,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, September 20, 2021, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/WPM-2021-10-Extending-FFCRA-WIC-Waivers.pdf.

[5] This report was prepared with support from Linnea Sallack, an independent consultant formerly with the Altarum Institute and the California WIC program.

[6] Zoë Neuberger, “Modernizing and Streamlining WIC Eligibility Determination and Enrollment Processes,” CBPP, January 6, 2017, www.cbpp.org/wicstreamlining.

[7] Recipients of TANF assistance are adjunctively income eligible for WIC, but recipients of other TANF-funded benefits or services are not. See 7 C.F.R. §246.7(d)(2)(vi)(A)(2).

[8] State agencies are also permitted to accept documentation of participation in other state-administered programs that routinely document income and that have income eligibility limits at or below WIC’s. See 7 C.F.R. §246.7(d)(2)(vi)(B).

[9] In 2020, about 77 percent of WIC applicants participated in Medicaid, SNAP, or TANF. See Nicole Kline et al., “WIC Participant and Program Characteristics 2020,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, February 2022, p. 46, Table 4.1, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICPC2020.pdf.

[10] Lorrene Ritchie et al., “Multi-State WIC Participant Satisfaction Survey: Learning from Program Adaptations During COVID,” National WIC Association, December 13, 2021, https://thewichub.org/multi-state-wic-participant-satisfaction-survey-learning-from-program-adaptations-during-covid/.

[11] For suggestions regarding protecting the privacy and confidentiality of data, see Privacy and Security Considerations in Hilary Dockray et al., “Launching New Digital Tools for WIC Participants—A Guide for WIC Agencies,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Social Interest Solutions, and National WIC Association, February 25, 2019, p. 42, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/launching-new-digital-tools-for-wic-participants#p3PrivacyAndSecurity.

[12] WIC agencies are required to certify applicants within 10 or 20 days of their application, depending on their nutrition risk. (See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(f)(2).) When checking adjunctive eligibility to recertify an existing participant, checking up to 30 days in advance of recertification would not violate those processing standards.

[13] Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Case Study: Maricopa County, Arizona,” CBPP, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/8-30-19fa-casestudies-maricopa-county.pdf.

[14] For example, after Colorado conducted training on an existing policy allowing for the use of electronic documents for certification, the share of temporary certifications made permanent with electronic documents rose from 43 percent to 65 percent. Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Case Study: Colorado,” CBPP, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/8-30-19fa-casestudies-colorado.pdf.

[15] CBPP, “Assessing Your WIC Certification Practices,” https://www.cbpp.org/wiccertificationtoolkit.

[16] Ritchie et al., op. cit.

[17] Kline et al., Table 3.1.

[18] Under federal rules, the WIC agency must require the applicant to sign a statement specifying why they cannot provide documentation of income. See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(d)(2)(v)(C).

[19] Unlike applicants who have income but no documentation of it, applicants with no income are not required to sign a statement specifying why they cannot provide documentation of income. See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(d)(2)(v)(C).

[20] See Debra Whitford, “WIC Policy Memorandum #2013-3 Income Eligibility Guidance,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, April 26, 2013, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/2013-3-IncomeEligibilityGuidance.pdf.

[21] See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(d)(2)(v)(D).

[22] Kathryn Cronquist, “Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2019,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, March 2021, Table 3.3, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/characteristics-snap-households-fy-2019.

[23] Zoë Neuberger, “Nutrition Provisions in New House Build Back Better Legislation Could Substantially Reduce Children’s Food Hardship,” CBPP, November 5, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/nutrition-provisions-in-new-house-build-back-better-legislation-could.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: