On May 31, the Social Security Board of Trustees issued its annual report on the program’s financial status.[1] Social Security does not face an immediate crisis, the trustees’ report shows, but it does face a funding shortfall two decades from now that the President and Congress should address reasonably soon so the program can fully meet its promises. Prompt action would permit changes that are gradual rather than sudden, and allow people to plan their work, savings, and retirement with greater certainty.

Several key points emerge from the new report:

- The trustees estimate that, in the absence of policy changes, the combined Social Security trust funds will be exhausted in 2033 — unchanged from last year’s report. That date fluctuates slightly in each trustees’ report depending on economic, demographic, and other variables; over the last two decades, it has ranged between 2029 and 2042, but the overall story has been consistent.

- After 2033, Social Security could pay three-fourths of scheduled benefits using its tax income if policymakers took no steps to shore up the program. (Those who fear that Social Security won’t be around at all when today’s young workers retire and that young workers will receive no benefits misunderstand the trustees’ projections.)

- The program’s shortfall is relatively modest, amounting to 1 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the next 75 years (and 1.6 percent of GDP in 2087, the 75th year). A mix of tax increases and benefit modifications — carefully crafted to shield recipients with limited means and to give ample notice to all participants — could put the program on a sound footing indefinitely. Social Security benefits are very modest. The average retiree or elderly widow receives just $15,000 a year from Social Security (and the average disabled worker even less); an unmarried elderly person, on average, has just $3,000 in annual income other than his or her Social Security. Accordingly, taxes should make up a large proportion of a solvency package.

- Policymakers will have to replenish the Disability Insurance trust fund by 2016. They should try to do so as part of a comprehensive solvency package, because the retirement and disability components of Social Security are closely woven together. Pending action on a balanced and well-designed solvency package, it is reasonable to reallocate taxes between the disability and retirement programs, as policymakers have often done in the past.

The trustees’ report focuses on the outlook for the next 75 years — a horizon that spans the lifetime of just about everybody now old enough to work. The trustees expect the program’s tax income to climb slightly from today’s levels, remaining near 13 percent of taxable payroll.[2] (Taxable payroll — the wages and self-employment income up to Social Security’s taxable maximum, currently $113,700 a year — represents slightly over one-third of GDP.) Meanwhile, the program’s costs are expected to climb to nearly 18 percent of taxable payroll — up from slightly under 14 percent today, largely due to the aging of the population. Interest earnings, long an important component of the trust funds’ income, will shrink after the mid-2020s and eventually disappear unless lawmakers take steps to restore solvency. Over the entire 75-year period, the trustees put the Social Security shortfall at 2.72 percent of taxable payroll; the shortfall is concentrated in the later decades of the projection. Expressed as a share of the nation’s economy, the 75-year shortfall is 1 percent of GDP.

Both of these widely cited figures — the shortfall as a share of taxable payroll and as a percentage of GDP — include a buffer that allows for a target trust fund balance in 2087 (the end of the 75-year period). Without that buffer — which is set at 100 percent of the next year’s estimated Social Security outlays — the shortfall would be 2.6 percent of taxable payroll or 0.9 percent of GDP.[3]

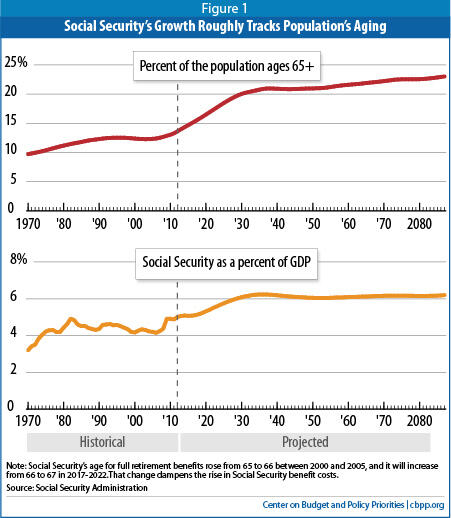

The program’s costs will grow steadily for the next 25 years and then stabilize. The trustees expect its cost to pass 17 percent of taxable payroll in the 2030s and barely grow thereafter. (As a percentage of GDP, outlays will rise from 5 percent today to 6.2 percent in the 2030s, and then remain close to that level.) While Social Security provides a safety net to people of all ages — to young children and their surviving parents who have lost a family breadwinner, to working-age adults who have suffered a serious disability, and to retired workers and elderly widows and widowers — about three-fourths of its benefits go to people age 65 or older. The share of the population that is 65 or older will climb steeply through 2035, from one in seven Americans today to slightly over one in five by the 2030s, and then inch up thereafter. The growth in Social Security’s cost as a percentage of GDP roughly mirrors that pattern.[4] (See Figure 1.) This reiterates that Social Security’s fundamental challenge is demographic, traceable to a rising number of beneficiaries rather than to escalating costs per beneficiary.

The size of the shortfall over the next 75 years is slightly larger than in the 2012 report (see Table 1). On balance, the entire slippage — which equals 0.05 percent of taxable payroll over 75 years — stems from the simple passage of another year; the 75-year valuation period now goes through 2087, rather than 2086, and thus adds one remote year with a significant deficit. The extension of most of the Bush-era tax cuts in the year-end “fiscal cliff” deal slightly worsened the Social Security outlook — by 0.15 percent of taxable payroll relative to “current law” as it stood before the deal, under which all of the Bush tax cuts were slated to expire — because it reduced the income taxes that more affluent beneficiaries pay on their Social Security benefits. (Those income tax revenues are credited to the trust funds). A variety of other factors, on balance, improved the outlook slightly.

At first blush, the projected deficit — 2.72 percent of taxable payroll — appears to be the largest projected in the last two decades (see Table 1). In the 1994-2012 reports, the 75-year deficit averaged a little over 2 percent of taxable payroll, and it has fluctuated within a fairly narrow range. Those figures are not, however, strictly comparable, because the period covered by the reports has shifted. The 1994 report, for example, spanned the period through 2068; this year’s report goes through 2087. Each one-year shift in that “valuation period” moves the 75-year balance further into the red by a small amount, so it is not entirely fair to compare today’s actuarial deficit with one estimated in the 1990s. Unlike the program’s deficit, the date of trust-fund exhaustion is not affected by the 75-year valuation period, and it has ranged between 2029 and 2042. In short, trustees’ reports over the last two decades have told a consistent story, although they have not yet spurred policymakers to action.

Table 1

Trustees’ Estimates Have Fluctuated But Tell a Consistent Story |

| |

Change in actuarial balance since previous report due to… |

|

|

| |

Legislation and regulations |

Valuation period |

All other |

Total change |

Actuarial balance |

Year of exhaustion |

| 1994 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.61 |

-0.66 |

-2.13 |

2029 |

| 1995 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

-2.17 |

2030 |

| 1996 |

0.03 |

-0.08 |

0.03 |

-0.02 |

-2.19 |

2029 |

| 1997 |

0.03 |

-0.08 |

0.02 |

-0.03 |

-2.23 |

2029 |

| 1998 |

0.00 |

-0.08 |

0.12 |

0.04 |

-2.19 |

2032 |

| 1999 |

0.00 |

-0.08 |

0.20 |

0.12 |

-2.07 |

2034 |

| 2000 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.24 |

0.17 |

-1.89 |

2037 |

| 2001 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.10 |

0.03 |

-1.86 |

2038 |

| 2002 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.06 |

-0.01 |

-1.87 |

2041 |

| 2003 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

-1.92 |

2042 |

| 2004 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.10 |

0.03 |

-1.89 |

2042 |

| 2005 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

-1.92 |

2041 |

| 2006 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

-0.03 |

-0.09 |

-2.02 |

2040 |

| 2007 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

0.13 |

0.06 |

-1.95 |

2041 |

| 2008 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

0.32 |

0.26 |

-1.70 |

2041 |

| 2009 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.25 |

-0.30 |

-2.00 |

2037 |

| 2010 |

0.14 |

-0.06 |

0.00 |

0.08 |

-1.92 |

2037 |

| 2011 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.25 |

-0.30 |

-2.22 |

2036 |

| 2012 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.39 |

-0.44 |

-2.67 |

2033 |

| 2013 |

-0.15 |

-0.06 |

0.16 |

-0.05 |

-2.72 |

2033 |

Note: “All other” changes include effects of economic, demographic, and disability assumptions and any changes in the actuaries’ methods and models.

Source: Annual trustees’ reports. All figures (except year of exhaustion) are expressed as a percentage of taxable payroll over 75 years. Details may not add to totals due to rounding. Data are for the combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance trust funds. |

Some commentators cite huge dollar figures that appear in the trustees’ report, such as the nearly $10 trillion shortfall through 2087 (or even the $23 trillion shortfall through eternity, a figure whose validity many experts question[5] ). Except over relatively short periods, however, it is not useful to express Social Security’s income, expenditures, or funding gap in dollar terms, which does not convey a sense of the economy’s ability to support the program. Expressing them in relation to taxable payroll or GDP, in contrast, puts them in proper perspective. Over the next 75 years, for example, taxable payroll — discounted to today’s dollars just as the $10 trillion shortfall figure is — will exceed $370 trillion, and GDP will be over $1,000 trillion. The shortfall over the next 75 years, as noted, equals about 2.6 percent of taxable payroll and 0.9 percent of GDP.[6]

The 2010 trustees’ report showed a small but significant improvement in Social Security’s finances due to the health reform law, which the actuaries expect will shift some employee compensation from (nontaxable) fringe benefits to (taxable) wages. That’s no longer new, but is worth noting. Repealing health reform would not only leave many millions of people uninsured and jettison various cost-saving measures in Medicare, but it would also harm the Social Security outlook.

The “fiscal cliff” deal — the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, enacted on January 2, 2013 — permanently extended most of the tax cuts originally passed in 2001 and 2003.[7] That will result in a loss of future income-tax revenue credited to the Social Security trust funds.

The partial payroll-tax holiday — a temporary reduction of 2 percentage points in the tax rate for employees and the self-employed — expired at the end of 2012. The holiday delivered a boost to workers’ paychecks — and to the economy — in 2011 and 2012, but lawmakers chose not to extend it or to replace it with better-targeted temporary tax relief for low-paid workers.[8] The holiday caused no harm to Social Security, because a transfer from the Treasury’s general fund to the trust funds (estimated to total slightly over $220 billion) fully offset the revenue loss, leaving the trust funds unaffected.[9]

Key Dates and What They Mean

2033 is the “headline date” in the new trustees’ report, because that is when the combined Social Security trust funds are expected to run out of Treasury bonds to cash in. At that point, if nothing else is done, benefits would have to be cut to match the program’s annual tax income. The program could then pay 77 percent of scheduled benefits, a figure that would slip to 72 percent by 2087. Contrary to popular misconception, benefits would not stop.

Although the exhaustion date attracts keen attention, the trustees caution that their projections are uncertain. For example, while 2033 is their best estimate of when the trust funds will be depleted, they judge there is an 80 percent probability that trust fund exhaustion will occur sometime between 2029 and 2039 — and a 95 percent chance that depletion will happen between 2028 and 2044. Slightly more sanguine estimates that the Congressional Budget Office issued last year suggest there is an 80 percent probability that the combined trust funds would be exhausted between 2029 and 2045.[10] In short, all reasonable estimates show a long-run problem that needs to be addressed but not an immediate crisis.

Two other, earlier dates also receive attention but have little significance for Social Security financing:

- 2010 marked the first year since 1983 in which the program’s total expenses (for benefits and administrative costs) exceeded its tax income (from payroll taxes and income taxes that higher-income beneficiaries pay on a portion of their Social Security benefits). That was long expected to happen in the mid-2010s as demographic pressures built; the economic downturn led it to occur several years sooner. The trust funds are nevertheless still growing, chiefly because of the interest income they receive on their Treasury bonds. In 2012, for example, Social Security’s interest income of $109 billion more than offset its so-called cash deficit of $55 billion, leading the trust funds to grow by $54 billion.[11]

- 2021 will be the first year in which the program’s expenses exceed its total income, including its interest income. At that point, the trust funds — after peaking at $2.9 trillion — will start to shrink as Social Security redeems its Treasury bonds to pay benefits.

Neither of these dates affects Social Security beneficiaries. From 1984 through 2009, Social Security collected more in taxes each year than it paid out in benefits, lent the excess revenue to the Treasury, and received Treasury bonds in return. Together with compound interest, that accounts for the $2.7 trillion in Treasury bonds that the trust funds hold today.

The drafters of the 1983 Social Security amendments purposely designed program financing in this manner to help pre-fund some of the costs of the baby boomers’ retirement. The interest income from the trust funds’ bonds, as well as the eventual proceeds from redeeming the bond principal, will enable Social Security to keep paying full benefits until 2033. Of course, policymakers should restore Social Security’s long-run solvency well before then. Social Security’s diminishing cash flow does affect the task of the Treasury, which manages the government’s overall financing needs. Nevertheless, the bonds have the full faith and credit of the United States government, and — as long as the solvency of the federal government itself is not called into question — Social Security will be able to redeem its bonds just as any private investor might do.[12]

The report reminds policymakers that they must act reasonably soon to replenish the Social Security disability fund. Most analyses of the trustees’ report — including this one — focus on the combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) trust funds, commonly known as the Social Security trust funds. In fact, these two trust funds are separate, and the DI trust fund faces exhaustion in 2016. (The much bigger OASI fund would last until 2035. Combined, the two funds would be depleted in 2033.)

DI’s insolvency is not a surprise or a crisis (see box, below). We strongly urge policymakers to address DI’s pending depletion in the context of action on overall Social Security solvency. Both DI and OASI face fairly similar long-run shortfalls; DI simply requires action sooner. And key features of Social Security — including the tax base, the benefit formula, and cost-of-living adjustments — are similar or identical for the two programs. In addition, most DI recipients are close to or past Social Security’s early-retirement age of 62. Tackling DI in isolation would leave policymakers with few — and unduly draconian — options and require them to ignore the strong interactions between Social Security’s disability and retirement components.

However, if policymakers are not able to agree in time on a sensible solvency package, they should reallocate revenues between Social Security’s retirement and disability funds — a traditional and historically noncontroversial action that has been taken numerous times in the past between the two trust funds, in either direction.[13]

Policymakers need to get Social Security reform right. Nearly every American participates in Social Security, first as a worker and eventually as a beneficiary. The program’s benefits are the foundation of income security in old age, though they are modest both in dollar terms (elderly retirees and widows receive an average Social Security benefit of $15,000 a year) and compared with benefits in other countries (Social Security benefits replace a smaller share of pre-retirement earnings than comparable programs in most other developed nations).[14] In fact, the median income of elderly married couples from all sources other than Social Security equaled just $23,000 in 2010; for non-married elderly people (including widows and widowers), median income from other sources was only $3,000.[15] Moreover, millions of beneficiaries have no income other than Social Security.[16]

Because Social Security benefits are so modest and make up the principal source of income for most recipients, policymakers should restore solvency through a mix of revenue increases and benefit changes, with increased revenues contributing at least half (and preferably a substantial majority) of the savings. Revenues could come from raising the maximum amount of wages subject to the payroll tax (which now encompasses only about 83 percent of covered earnings, well short of the 90 percent figure envisioned in the 1977 Social Security amendments); broadening the tax base by subjecting voluntary salary-reduction plans, such as cafeteria plans and health care Flexible Spending Accounts, to the payroll tax (as 401(k) plans and similar retirement accounts are); and raising the payroll tax rate modestly at some point in the future.

Future workers are expected to be more prosperous than today’s. Under the trustees’ assumptions, the average worker will be almost 50 percent better off — in real terms — in 2040 than in 2013, and twice as well off by 2070. It is appropriate to devote a small portion of those gains to the payroll tax, while still leaving future workers with much higher take-home pay. Social Security is a popular program, and poll respondents of all ages and incomes express a willingness to support it through higher taxes.[17]

Although Social Security faces no imminent crisis, policymakers should act sooner rather than later to restore its long-term solvency. As the Center’s President Robert Greenstein explained in a paper that he co-authored in 2010 with Charles Blahous, one of Social Security’s two current public trustees, the sooner policymakers act, the more fairly they can spread out the needed adjustments in revenue and benefit formulas, and the more confidently people can plan their work, savings, and retirement.[18]

Social Security changes need to be designed with great care. Treating Social Security as just one component of a big deficit-reduction package can lead policymakers to reach for “off-the-shelf” options. Historically, however, most major Social Security legislation has moved through Congress on its own and not as part of large deficit-reduction packages. That tradition has allowed greater attention to the program’s adequacy, equity, and relationship to other programs such as Medicare and the needs-tested Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, which is distinct from Social Security but interacts with it in important ways.

Policymakers need to design reforms judiciously so that Social Security continues to be the most effective and successful income-security program in the nation’s history.

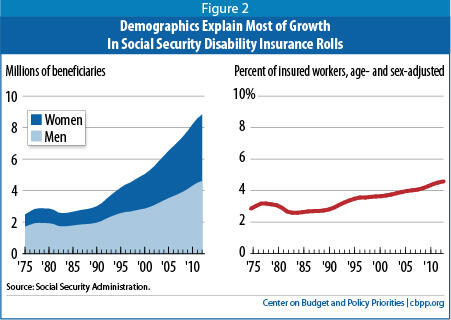

In December 2012, 8.8 million people received disabled-worker benefits from Social Security. (Payments also went to some of their family members: 160,000 spouses and 1.9 million children.) The number of disabled workers has doubled since 1995, while the working-age population — conventionally described as people age 20 through 64 — has increased by only about one-fifth. But that comparison is deceptive. Over that period:

- Baby boomers aged into their high-disability years. People are roughly twice as likely to be disabled at age 50 as at age 40 and twice as likely to be disabled at age 60 as at age 50. As the baby boomers (people born in 1946 through 1964) have grown older, the number of disability cases has risen.

- More women qualified for disability benefits. In general, workers with severe impairments can get disability benefits only if they have worked for at least one-fourth of their adult life and for five of the last ten years. Until the great influx of women into the workforce that occurred in the 1970s and 1980s, relatively few women met those tests; as recently as 1990, male disabled workers outnumbered women by nearly 2 to 1. Now that more women have worked long enough to qualify for disability benefits, the ratio has fallen to 1.1 to 1.

- Social Security’s full retirement age rose from 65 to 66. When disabled workers reach full retirement age, they begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits and cease receiving disability benefits. The increase in the retirement age has delayed that conversion for many workers. In December 2012, more than 450,000 people between 65 and 66 collected disability benefits; under the rules in place a decade ago, they would be receiving retirement benefits instead.

The Social Security actuaries express the number of people receiving disability benefits using an “age- and sex-adjusted disability prevalence rate” that controls for these factors. Over the 1995-2012 period, that rate rose from 3.5 percent of the working-age population to 4.6 percent. That’s certainly a significant increase, but not nearly as dramatic as some have painted (see Figure 2).

Not surprisingly, the rate has crept upward during periods of economic distress. Anecdotally and statistically, we know that many workers with physical or other health conditions turn to disability insurance when they can’t find jobs and exhaust their unemployment benefits.

When lawmakers last redirected some payroll tax revenue from OASI to DI in 1994, they expected that step to keep DI solvent until 2016. Despite fluctuations in the meantime, the current projection still anticipates depletion in 2016. DI’s depletion should not come as a surprise or be considered evidence that the program is out of control.