An examination of how the almost 79 million children under age 19 would fare under the House-passed health reform bill shows that the overwhelming majority likely would either see no change or be better off than under current law, with tens of millions better off.

Some have criticized the bill out of the belief that its phaseout of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at the end of 2013 would result in many millions of children being worse off than they are today. Some children could indeed be worse off under the House bill. These children would constitute a small fraction of the number of children who would gain under the bill, however, and would make up significantly fewer than 5 percent of the children in the country. [1]

In short, while there would be “winners” and “losers” — as is most often the case when a major part of government or the economy is restructured— children as a whole would be substantially better off. In particular:

- The Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2019, 36 million people who otherwise would be uninsured would gain coverage under the bill, a number that includes millions of children. For the first time in the nation’s history, all children legally residing in the United States would have a path to coverage.[2]

Despite the material in this analysis, we recommend that the Senate bill’s CHIP provisions be maintained in conference — along with as many of the House provisions as possible related to premium and cost-sharing subsidies for people purchasing coverage in the exchange, the rules governing the exchange and other insurance markets, Medicaid coverage and reimbursement rates, and the nature and applicability of the pediatric benefits package. The House provisions in these non-CHIP areas are stronger and more beneficial for children and families.

The Senate and House bills differ in a number of respects that would have significant impacts on children. The House bill would set the Medicaid income limit at 150 percent of the poverty line. The Senate bill would set this limit at 133 percent of the poverty line, which means that fewer children would move from separate state CHIP programs to Medicaid if CHIP did not continue. The Senate bill also has weaker benefit standards than the House bill for children’s coverage offered under employer-based plans, less adequate subsides for families that purchase coverage in the exchange, and weaker rules to ensure that the exchanges work well. It also does not merge the troubled individual insurance market into the health insurance exchange.

There is a strong argument that if the health insurance exchange were well designed in all key respects and Medicaid eligibility were expanded more broadly as under the House bill, children now in separate CHIP programs could successfully be transitioned to a combination of expanded Medicaid coverage, the exchange, and employer-coverage, as the House bill would do. But, as just noted, the Senate bill is significantly weaker in all of these areas, and most observers expect that the final legislation will generally be significantly closer to the Senate bill than to the House measure. Accordingly, for children to be best protected and served, the Senate bill’s CHIP provisions should be maintained in conference.

In short, the optimal outcome for children in the final legislation would appear to be a combination of the Senate CHIP provisions and as much of the House approach as can be secured on affordability, the rules for the exchange and other insurance markets, Medicaid, and the requirements related to the applicability of the pediatric benefits package to the exchange and employer-based coverage.

In addition, most of the children who do have coverage today would be as well off — or, for millions of children, better off — than they currently are.

- Over half of all children in the United States have employer-based coverage. (The number of children with employer coverage dwarfs the number covered through the Children’s Health Insurance Program.) In a major policy breakthrough, the House bill mandates that by 2018 all employer-based coverage in the United States must include an “essential benefits package” that includes dental, vision, hearing and mental health coverage for children, as well as well-baby and well-child care — and that may not charge any cost-sharing for preventive services or well-baby and well-child care.

- The 3.2 million children who have (often spotty) coverage through the individual insurance market also would gain, since beginning in 2013 they would now receive more comprehensive coverage that must include all of the same health services (noted above) that employer coverage would be required to carry. In addition, if their family income is below 400 percent of the poverty line, their families would receive premium subsidies, plus cost-sharing subsidies if their family income is below 350 percent of poverty.

- Another group of children that would gain consists of children in separate state CHIP programs who have incomes between 100 and 150 percent of the poverty line. These children would move from CHIP to Medicaid and would receive an expanded benefits package that includes Medicaid’s Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment benefit (EPSDT). Moreover, they no longer would face any premium charges and generally would face lower cost-sharing charges than they now face under CHIP.

- Children in state Medicaid expansion programs that are funded through CHIP would remain in Medicaid. Their coverage would be unchanged. The CHIP children whom the previous two bullets describe (those who have incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line and those who are enrolled in a CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion), all of whom would be as well or better off, constitute the majority of all CHIP children in the nation.

- The remaining children in CHIP, who represent only a minority (about 42 percent) of CHIP children, according to a new Urban Institute study — and who represent fewer than 5 percent of the children in the United States — would move either to coverage in the exchange or to employer coverage.[3] Assessing whether these children are better or worse off is complex, with the fairest conclusion being that some would be as well or better off and some would be worse off. CHIP children whose parents are uninsured today but would gain coverage under the bill would generally be better off, because their entire family would now be covered. Extensive research shows that children are more likely to receive needed health care (even if the children are insured) if their parents also have coverage. Extending affordable coverage to these parents should also ease pressure on family budgets, enabling parents to devote more resources to their children’s needs.

At the same time, children moving from CHIP to the exchange or employer coverage whose parents already have coverage could be worse off. They could receive a somewhat smaller benefit package and could pay somewhat more. The degree to which they would be worse off would be moderated under the House bill by the mandate of a strong benefit package for children in both the exchange and in employer coverage, and by the bill’s strong subsidies for premiums and cost-sharing charges for families that have incomes in the CHIP income range and purchase coverage in the exchange.

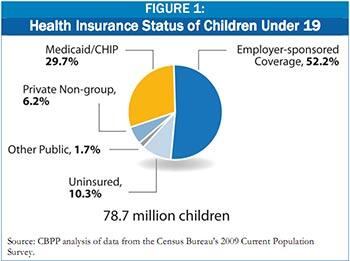

The chart below indicates how children were covered in 2008. It should be noted that over the course of a year, many children move between the coverage categories shown in the chart. A parent could lose or gain a job, leading a child to lose or gain employer coverage. Changes in income could qualify or disqualify a child for public coverage. Many children drop off of public coverage and become uninsured for procedural reasons such as not submitting sufficient paperwork by various deadlines. A study that examined the movement of children across categories of coverage found little variation in the distribution of public and private coverage from year to year, but a large amount of movement across the coverage categories. [4]

It also is important to note that the chart understates the percentage of children enrolled in Medicaid. Comparisons of data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) and data on Medicaid enrollment from the Centers on Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) show that the CPS undercounts the number of people actually enrolled in Medicaid.[5]

As Figure 1 shows, a little more than half of all children in the United States are covered through employer plans. These children would keep their employer coverage (absent any change in their parents’ job status or offer of employer coverage).

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the House bill would result in an overall increase of 6 million people with employer coverage by 2019 relative to current law. It is likely that both more adults and more children would have employer coverage under the House bill, because employers who offer coverage would be required to contribute to the cost of dependent coverage. They would pay a penalty if they did not do so.

Specifically, employers would be required to contribute at least 65 percent of the cost of dependent coverage. [6] Workers who have incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line and whose employers offer coverage would nevertheless be eligible for premium credits to help them buy coverage in the exchange instead, if the employee share of the cost of employer coverage for the family would exceed 12 percent of the family’s income.

In general, after five years, all employer plans would have to meet the same standards as plans offered in the exchange. These standards, which are impressive, include the following:

- Plans would be required to provide a package of essential benefits, including well-baby and well-child care, dental coverage, vision and hearing services, and equipment and supplies for children under 21 years of age, in addition to a comprehensive of list of services for both children and adults;

- There could be no cost-sharing for preventive services, including well-baby and well-child care;

- There could be no annual or life-time limits on benefits;

- Plans would have to meet new standards for the adequacy of provider networks to ensure access to covered services;

- Plans would have to give parents an option to cover their dependent children up to the age of 27.

About 3.2 million children currently get coverage in the individual insurance market. These children would be much better off under the House bill, for two main reasons:

- All families with incomes under 400 percent of the poverty line would be eligible for premium credits in the exchange to help them purchase coverage, as well as credits to lower their deductible and co-payment charges if they are below 350 percent of the poverty line. Low- and moderate-income families that purchase coverage in the individual market today generally do so without any assistance, regardless of their income.

- Once health reform is implemented, individual insurance could be offered only through the exchange. And unlike in the current individual market, where plans often have high deductibles and cost-sharing and commonly feature limited benefits,[7] all health plans available in the exchange would have to offer the essential benefit package the bill mandates and also would have to meet all of the standards just described for employer plans. Furthermore, insurers would no longer be allowed to exclude or limit coverage for pre-existing conditions or to charge more for covering people who have health problems.

In addition, coverage would be available in the exchange for a major group of children who are uninsured today — those whose family incomes are above the eligibility levels for CHIP but whose families do not have an offer of employer coverage. Many of these children’s parents cannot afford coverage now in the individual market, particularly those whose children have health problems and thus are charged more in the individual market in most states (if they are able to obtain an offer of coverage at all).

The House bill would extend Medicaid to children and adults with incomes up to 150 percent of the poverty line — $33,075 for a family of four in 2009. States whose Medicaid programs now cover children with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line, as well as states that use CHIP funds to expand Medicaid, would be required to maintain their higher Medicaid income limits. As a result, all children eligible for Medicaid today would be able to remain in Medicaid.[8]

States currently must cover children under age 6 in Medicaid if their family income is below 133 percent of the poverty line, and children aged 6 through 18 if their family income is below 100 percent of the poverty line. Raising the minimum income level to 150 percent of the poverty line for all children under 19 would raise Medicaid eligibility levels in more than half of the states. In all of these states, children with incomes between the state’s Medicaid income eligibility level and 150 percent of the poverty line currently are covered by CHIP. [9]

The Urban Institute estimates that 42 percent of all children enrolled in separate CHIP programs in 2007 would move to Medicaid because of this increase in the Medicaid income limits.[10] When these children are added to those in CHIP-funded Medicaid expansions who would remain in Medicaid, the Urban Institute estimates that 58 percent of children in CHIP would be eligible for Medicaid under the House bill. The remaining 42 percent of children in CHIP would move to either the exchange or employer coverage.

Children who move to Medicaid from separate CHIP programs would be better off. Medicaid does not charge premiums and generally has lower cost-sharing charges than CHIP. In addition, all children in Medicaid receive Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefits, which are more comprehensive than benefits provided by most separate CHIP programs.

A modest but not insignificant percentage of children — fewer than 5 percent of children legally residing in the United States — would move from separate CHIP programs to employer coverage or the new health insurance exchange.[11] Because of the House bill’s employer responsibility requirement, those children whose parents have an offer of coverage that meets the standards in the House bill would enroll in their parents’ employer plan. Families without an offer of employer coverage would be able to purchase coverage through the exchange, with families of children who now are eligible for CHIP being eligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies to help them afford coverage and health care services. Children who move from CHIP to the exchange would do so at the start of 2014, one year after the exchange starts operating, which should provide time for initial “bugs” in the exchange to be worked out.

The following are a few criticisms that have been raised about moving children from CHIP to the exchange that have no applicability to the House bill. Some of the confusion apparently stems from a misunderstanding of the specific provisions of the House bill.

- Won’t infants, children, and pregnant women now eligible for Medicaid who have gross incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line lose their Medicaid coverage? No. The House bill requires states to permanently maintain their current Medicaid eligibility levels for all of these groups. Every child who is eligible for Medicaid today would retain that eligibility under the House bill.

- Won’t legal immigrant children who move from CHIP to the exchange be subject to a five-year waiting period? Not only is this belief mistaken, but the rules for coverage of such children would actually be more favorable in the exchange than in CHIP. In CHIP, states have the option of imposing a five-year waiting period on these children. But waiting periods for legal immigrant children would not be allowed in the exchange.

- Won’t immigrants be prohibited from purchasing coverage in the exchange? No. Any immigrant lawfully residing in the United States would be allowed to purchase coverage in the exchange and, if the immigrant’s income was below 400 percent of the poverty line, to receive a subsidy to help cover the cost. (Undocumented immigrants also would be allowed to purchase coverage in the exchange, but they would be ineligible for a subsidy.)

- Won’t health insurance costs be raised for children in the exchange because they will be pooled with older adults? Premium costs for everyone under 400 percent of the poverty line would be limited to a specified percentage of their income and hence would not be affected by the pooling. The only children whose premium costs could be affected by the broad pooling in the exchange would be those who have incomes above 400 percent of the poverty line. There is no state in the country in which children with incomes that high are eligible for CHIP.

It is difficult to say what portion of these children would be better off and what portion would be worse off. On the one hand, the contributions that families would make toward employer coverage or an exchange plan would generally be greater than the premiums these families now pay for coverage in CHIP. On the other hand, these higher contributions would be for coverage for the entire family, and studies have shown significant benefits to children when all family members are covered.[12] Cost-sharing would also generally be higher under employer coverage and exchange plans. Low-income families would be eligible for separate cost-sharing subsidies in the exchange, and no cost-sharing would be charged for preventive services.[13]

This raises a difficult question of comparison. Is a family that pays, say, 2.5 percent of income to cover its children through CHIP better or worse off if the parents go from being uninsured to having coverage but the family now pays 6 percent of income for family coverage in the exchange and the benefit package is modestly less generous than the CHIP package? Our assessment would be that on the whole, such a family and children should be considered better off because of the big gain resulting from the parents no longer being uninsured. In any event, it would be dubious to classify the children in such a family as having suffered serious injury.

In addition, all exchange plans and eventually all employer plans would be required to cover well-baby and well-child care, dental, vision and hearing services, mental health and substance abuse treatment and many other services that children may need.

A final point is that unlike the current CHIP program, in which funding is capped and states may set enrollment ceilings and impose waiting lists, the new federal premium and cost-sharing credits would be available for all of those who qualify. Families and children would never face waiting lists. Nor would their coverage ever be dependent upon governors and state legislatures providing sufficient matching funds for the program.