- Home

- Two Tax Cuts Primarily Benefiting Millio...

Two Tax Cuts Primarily Benefiting Millionaires Slated To Take Effect In January

Summary

Even before Hurricane Katrina, large deficits were projected far into the future, with the nation’s debt burden ultimately swelling to unsustainable levels. The relief and recovery from Hurricane Katrina is estimated to cost $100 billion to $200 billion, adding to the nation’s mounting debt. Debate has now begun about whether in the face of these costs and the grim long-term fiscal outlook, some belt-tightening and “shared sacrifice” are in order.

The budget reconciliation bills that Congress is slated to consider this fall will not help. Taken together, the two bills will increase deficits by more than $35 billion over five years. Under these bills, $35 billion in cuts in programs such as Medicaid and food stamps will be used not to reduce the deficit, but to offset a portion of the $70 billion that the reconciliation tax-cut bill will cost.

On September 16, President Bush said further budget cuts will be needed. The Administration presumably intends these cuts to come primarily in domestic programs. One obvious step, however, is being overlooked: Two tax cuts enacted in 2001 that are not yet in effect — and will only start taking effect on January 1 — could be reconsidered as a way of helping to defray some of the costs of Katrina relief and recovery. These two tax cuts will benefit only high-income households (primarily millionaires), will do little for the economy beyond further increasing the deficit, and were not even requested by President Bush in the first place. (They were added by Congress.)

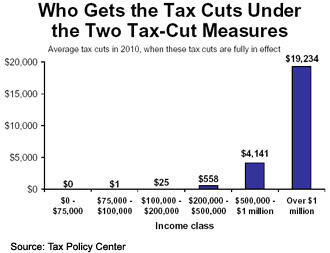

The highly respected Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center reports that households with incomes of more than $1 million a year — the richest 0.2 percent of the U.S. population — already are receiving tax cuts averaging $103,000 this year, before these two new tax cuts take effect. The Tax Policy Center finds that the two tax-cut measures in question will give these “millionaires” nearly another $20,000 a year in tax cuts, when the measures are phased in fully.

This raises the question of whether the nation should proceed with these tax cuts at a time when many Katrina survivors remain in difficult straits, when huge sums are being discussed for Katrina relief and recovery, and when cuts in domestic programs — including programs for the poor — are slated for Congressional consideration this fall as part of the reconciliation bills.

President Clinton on the Today Show, September 16, 2005

Matt Lauer: What sacrifices would you ask the American people to make to pay those [hurricane relief and Iraq war] bills?

President Clinton: I would repeal the tax cuts for upper-income people. I myself have gotten 4 tax cuts while young Americans have gone off to risk their lives in Iraq and Afghanistan, while we've had this massive natural disaster. We've run up this huge deficit. How are we covering this money? We are borrowing the money from China, Japan, Korea, Saudi Arabia to pay for the suffering of our people in the Gulf area, to pay for the Iraq War, and to cover my tax cuts — and we are expecting our children to pay the bill. We've made a decision to lower the living standards of our children and grandchildren and to soak other people around the world who don't have the money we do, by and large, to cover our self-indulgence.

The facts about these two tax cuts are as follows:

- Under the tax code as it operates today, these are limits on the value of the personal exemptions and itemized deductions that people at high income levels can take. The two tax cuts scheduled to start taking effect in January would phase out these limits and repeal them entirely by 2010. (See the box on page 6 for a further description of the two tax-cut measures.)

- President Bush did not ask for these tax cuts. Congress added them to the 2001 tax-cut bill, which was enacted at a time when policymakers assumed budget surpluses would surpass $5 trillion over the coming decade.

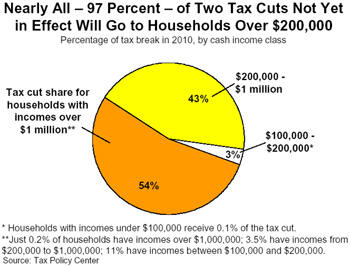

- According to the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, a majority of the tax cuts from these two tax-cut measures — 54 percent of these tax cuts, to be precise — will go to the 0.2 percent of households that have annual incomes of more than $1 million a year. These households will receive added tax cuts averaging nearly $20,000 a year from these two tax-cut measures, when the measures are fully in effect.

- Some 97 percent of the tax cuts from these two measures will go to the 3.7 percent of households that have incomes of over $200,000 a year.

- Virtually none of the tax cuts from these measures will go to families in the middle of the income spectrum.

- As noted, these tax cuts will phase in fully by 2010. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates they will reduce revenues by $9 billion in 2010, and by $16 billion in 2015. The ten-year cost of these provisions in the first ten years that they will be fully in effect (2010 through 2019[1]) will be $146 billion.[2] When the associated interest payments on the debt of $51 billion are added in, the cost rises to $197 billion over this ten-year period.

- These estimates understate the cost of the two tax cuts. These estimates are based on Joint Tax Committee estimates that do notassume continuation of relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax. The Joint Tax estimates instead assume that a swelling AMT will cancel out a portion of these tax-cut benefits, reducing their costs. Virtually all observers expect, however, that AMT relief will be extended. With AMT relief in place, these tax cuts will cost significantly more than the amounts cited here.

- Over time, the costs of these two tax cuts will exceed the costs of relief and recovery from Hurricane Katrina (assuming that the tax cuts are extended beyond 2010, as the President has proposed).

Will Today’s Policymakers Have the Courage of Ronald Reagan and the first President Bush?

When substantial budget deficits emerged in 1982, President Ronald Reagan agreed to undo a significant share of the tax cuts he had signed the previous year. In 1990, facing large deficits, President George H. W. Bush had the courage to change his position on taxes and to play a leadership role in developing a major bipartisan deficit-reduction package that both raised revenues and cut spending. Today, with deficits projected as far as the eye can see and additional costs now looming, the question is whether President George W. Bush and Congressional leaders are willing even to consider and discuss forgoing these two tax cuts, which were enacted at a time when large surpluses were thought to exist.

This question takes on particular poignancy because the two tax cuts in question are simply measures that repeal two revenue-raising provisions that the first President Bush negotiated and signed into law in 1990, to help address troubling budget deficits. Forgoing these two tax cuts would advance the cause of fiscal discipline. It also could serve as an alternative to some troubling budget cuts that could harm some of the nation’s poorest and most vulnerable citizens.

These issues are examined in more detail below.

| Distribution of the Two Tax Cuts, 2010 | |||

| Income Group | Share of Households | Share of the Tax Cuts | Average Tax Cut |

| $0-75 | 77.1% | 0.0% | $0 |

| 75-100 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 1 |

| 100-200 | 10.9 | 3.2 | 25 |

| 200-500 | 3.0 | 19.1 | 558 |

| 500-1,000 | 0.5 | 24.0 | 4,141 |

| More than $1 million | 0.2 | 53.5 | 19,234 |

| Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. | |||

The Two Tax Cuts that Have Not Yet Begun to Take Effect

One of the tax cuts slated to start taking effect in January repeals a provision of the current tax code that scales back the size of itemized deductions that high-income taxpayers may take. The other measure taking effect on January 1 repeals another provision of the tax code under which the personal exemption is phased out for households with high incomes. (See the box on page 6 for a fuller description of these measures.) These two provisions of current law will start to be phased out in 2006 and be eliminated entirely in 2010.

The Two Tax Cuts Are Regressive

The Tax Policy Center of the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution has analyzed these two tax-cut measures. The Tax Policy Center has found:

- Some 54 percent of the tax cuts from these two measures will go to households with incomes of more than $1 million a year, the top 0.2 percent of households.[3],[4] Another 43 percent of the tax-cut benefits will go to the 3.5 percent of households with incomes between $200,000 and $1 million. Thus, 97 percent of the tax cuts from these two provisions will go to the 3.7 percent of households with incomes over $200,000.

- That leaves only 3 percent of the tax-cut benefits for the 96 percent of U.S. households with incomes below $200,000. That 3 percent of the tax cuts will go almost entirely to households in the $100,000-$200,000 range. Essentially none of the benefits will flow to families with incomes under $100,000 (see table).

- High-income households already are receiving extremely large tax cuts without these two new tax-cut measures. According to the Tax Policy Center, households with incomes of more than $1 million are receiving tax cuts that average $103,000 this year, and will receive tax cuts averaging $108,000 in 2010, from the other income-tax cuts included in the 2001 and 2003 tax-cut laws. (The Tax Policy Center estimates that when the effects of repeal of the estate tax are taken into account, those in this very high income group will receive tax cuts averaging $133,000 in 2010 from tax cuts other than the two measures discussed here.) The Tax Policy Center’s analysis shows that adding in the two tax-cut provisions slated to start taking effect in 2006 will bring the total tax cut for people with incomes over $1 million to $152,000, on average, in 2010. (These figures are in 2010 dollars.)

The Role of the Two Presidents Bush

These two provisions of the tax code were adopted on a bipartisan basis in 1990, as part of the deficit-reduction package enacted that year, in no small part because of the leadership of the first President Bush. These measures were part of a large, balanced, and highly effective deficit-reduction package enacted that year that featured shared sacrifice. The package included both substantial program reductions and substantial tax increases. These two revenue-raising provisions were included in the package to direct more of the revenue increases to those who could most readily afford them.

In 2001, President George W. Bush did not propose elimination of these two revenue-raising provisions. Repeal of these provisions was added on Capitol Hill. Since then, the President has called for making these tax cuts permanent.

What Other Recent Republican Presidents Have Done

Faced with a need to address unanticipated deficits, other recent Republican Presidents have moderated their stances on taxes and opted for a more balanced approach. They have led even when some of their supporters staunchly opposed such a policy change. As noted, Ronald Reagan agreed to scale back his tax cuts in 1982 when the fiscal situation deteriorated. President George H.W. Bush altered his position on taxes in 1990 in the face of difficult fiscal realities. A question today is whether, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, President George W. Bush would be willing to consider the modest step of forgoing two tax cuts for the affluent that are not yet in effect, or whether he and Congressional leaders rule out any consideration of such a step. The early indications are not promising.

Tax Cuts Would Repeal Two Tax Provisions Enacted in 1990 Deficit-Reduction Effort

The two provisions in question were enacted as part of the 1990 deficit-reduction package and made permanent in the 1993 deficit-reduction package. Under the 2001 tax-cut law, both would be phased out starting in 2006 and repealed entirely in 2010.

The first provision phases out the personal exemption for those at high income levels; it is known as the “personal exemption phase-out,” or “PEP” for short. The tax code provides for a personal exemption that taxpayers can use to shield some income from taxation. The personal exemption is set at $3,200 in 2005. The personal exemption phase-out provision reduces a tax filer’s total personal exemption amount by two percent for each $2,500 by which the tax filer’s income exceeds $218,950 for married couples in 2005 (or exceeds $145,950 for individuals).

The second provision limits the value of itemized deductions for taxpayers with high incomes. (This is sometimes referred to as the “Pease” provision, after the late Rep. Don Pease, who originally designed it.) The tax code allows taxpayers to reduce their taxable income either by the standard deduction or by an amount equal to the sum of an array of itemized deductions. About two-thirds of taxpayers use the standard deduction, while one-third — typically those with higher incomes — itemize deductions. Under this provision, certain itemized deductions are reduced for high-income taxpayers; the value of these deductions is reduced by an amount equal to three percent of the amount by which a taxpayer’s income exceeds $145,950 in 2005. Thus, a taxpayer with income of $245,950 would reduce his or her itemized deductions by $3,000 ($100,000 x 3 percent). If such an individual were in the 33 percent bracket, the provision would cause the individual’s tax liability to be $990 higher ($3,000 x 33 percent) than if this provision did not exist.a

a Note: Itemized deductions affected by the limit cannot be reduced by more than 80 percent under this provision.

End Notes

[1] This assumes the tax cuts will be extended beyond 2010, as the President has proposed.

[2] This assumes that the cost in 2015, as estimated by the Joint Tax Committee, will grow at the same rate as the economy in years after 2015.

[3] In its analyses, the Tax Policy Center examines the effects of the tax cuts on different “tax units.” These “tax units” include individuals and married couples who file income tax returns, as well as those who do not file (primarily because their incomes are below the minimum threshold for filing). As shorthand, this report uses the term “households” instead of “tax units.”

[4] These TPC distribution estimates reflect the assumption that provisions expiring before 2010, such as the capital gains and dividend tax cuts and relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax, will be extended through 2010. Without this assumption, the degree to which these tax cuts are concentrated on those with the highest incomes would be even greater.

More from the Authors

Recent Work: