Some policymakers are promoting another “repatriation tax holiday” to encourage multinational corporations to bring overseas profits back to the United States by offering them a temporary, very low tax rate on those profits. In particular, some have described a repatriation holiday as a “win-win” that would boost corporate investment and create jobs in the United States and also generate a tax windfall to help finance needed infrastructure spending. In reality, a repatriation tax holiday would accomplish neither goal and instead would worsen the nation’s fiscal and economic problems over time.

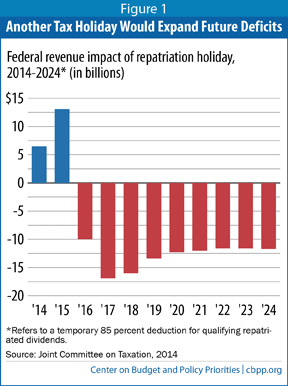

- A repatriation tax holiday would lose substantial federal revenue and swell budget deficits, so it couldn’t pay for highways, mass transit, or anything else. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) recently estimated that, while a second repatriation holiday (following the one enacted in 2004) would raise revenue for the first two years, it would cost $96 billion over ten years. Thus, rather than use the tax holiday to finance long-term infrastructure projects, the Treasury would have to borrow to pay for the tax holiday and then borrow again to pay for the infrastructure. (For more, see “Repatriation Holiday Costs Money So Can’t Offset Other Costs,” below.)

- The 2004 tax holiday did not produce the promised economic benefits, and a second one likely wouldn’t either. Firms largely used the profits that they repatriated during the 2004 holiday not to invest or create U.S. jobs but for the very purposes that Congress sought to prohibit, such as repurchasing their own stock and paying bigger dividends to shareholders. Moreover, many firms laid off large numbers of U.S. workers even as they reaped multi-billion-dollar benefits from the tax holiday and passed them on to shareholders. The top 15 repatriating corporations repatriated more than $150 billion during the holiday while cuttingtheir U.S. workforces by 21,000 between 2004 and 2007, a Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations report found.[2] (For more, see “2004 Tax Holiday Failed to Generate Promised Economic Benefits,” below.)

- A second tax holiday would increase incentives to shift income overseas. If the President and Congress enact a second tax holiday, corporate executives will likely conclude that more such tax holidays will come down the road, making these executives more inclined to shift income into tax havens (and hence less likely to invest in the United States). That’s why Congress, in enacting the 2004 tax holiday, explicitly warned that it should be a one-time-only event. (For more, see “Second Repatriation Holiday Would Be Even Costlier Mistake,” below.)

- A tax holiday would not likely boost domestic investment by freeing multinationals from cash restraints. Proponents of a new tax holiday argue that large multinationals are cash-constrained and would make significant, job-creating investments in the United States if they had access to their overseas earnings. The large stock repurchases that some multinationals made in recent years, however, (1) show that they already have easy access to large amounts of domestic cash and (2) suggest that multinationals would likely use additional cash from repatriation for more stock buy-backs, rather than new investments. Indeed, the ten companies with the largest stockpiles of foreign profits paid out more than $107 billion in cash to shareholders through share repurchases in 2013, suggesting that they are not cash-constrained. Moreover, seven of the ten companies with the largest stockpiles of foreign earnings in 2013 also ranked among the top ten U.S. companies by share repurchases. (For more, see “Evidence Contradicts Claim That Multinationals Are Cash-Constrained,” below.)

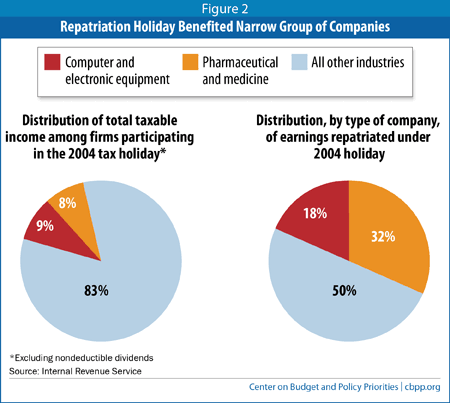

- Some of the biggest beneficiaries of a tax holiday would be firms that aggressively shifted income overseas. Technology and pharmaceutical companies have been particularly aggressive in shifting income abroad because they rely on intellectual property, which is relatively easy to shift to other countries to avoid taxes. Half of all repatriations from the 2004 tax holiday came from companies in these two industries. Large multinationals in the same industries would benefit disproportionately — and enormously — from a second tax holiday. (For more, see “Biggest Winners Would Include Firms That Have Aggressively Shifted Income Overseas,” below.)

- Policymakers can raise revenues by taxing offshore profits — and even dedicate the revenue to finance infrastructure projects — without enacting another repatriation holiday. President Obama and House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp both proposed to tax offshore earnings (and dedicate the resulting revenue to infrastructure investment). Their proposals, however, are measures to help transition the U.S. tax code to a reformed international tax system — not repatriation tax holidays. Chairman Camp would subject offshore tax-deferred profits to a compulsory tax as part of transitioning to a new international tax system, generating an estimated $170 billion of revenue over ten years that Camp would dedicate to the Highway Trust Fund.

Similarly, in his fiscal year 2015 budget, President Obama proposed to use temporary revenue from transitioning to a new corporate tax system to finance infrastructure investment. The President has made clear that his proposal is not a repatriation tax holiday, with his spokesperson saying: “The president does not support and has never supported a voluntary repatriation holiday because it would give large tax breaks to a very small number of companies that have most aggressively shifted profits, and in many cases, jobs, overseas.”[3] (For more, see “Transition Tax Offers Much Better Alternative,” below.)

U.S.-based corporations with foreign subsidiaries are taxed on their U.S. and foreign income. Generally, however, they pay no U.S. corporate tax on their foreign income until they “repatriate” it — that is, send it back to the U.S. parent corporation from abroad. This effectively allows such firms to defer payment of the U.S. corporate income tax on some of their overseas profits indefinitely.

This U.S. tax structure not only reduces federal revenues from what they would otherwise be, but it also gives U.S.-based multinationals a significant incentive to shift economic activity — and the reported profits on which they otherwise would have to pay U.S. tax — abroad.

In the 2004 American Jobs Creation Act (AJCA), Congress enacted a one-time “dividend repatriation tax holiday” that allowed firms to bring overseas profits back to the United States at a dramatically reduced tax rate during 2005 and 2006. Normally, corporations pay the difference between the U.S. corporate rate of 35 percent and the rate at which the foreign country taxes overseas profits earned in its jurisdiction. (To avoid double taxation, U.S. corporations get a tax credit for the taxes they have paid to foreign countries.)

The 2004 tax holiday allowed corporations to repatriate foreign-earned income at an effective tax rate of 5.25 percent; the average rate that they actually paid was even lower — just 3.7 percent — because they could use the foreign tax credits, cited above, to further reduce their tax.[4] During the holiday,large multinationals repatriated $362 billion in earnings, of which $312 billion qualified for the sharply reduced tax rate, according to the IRS.[5]

Proposals to provide another tax holiday have emerged periodically. A proposal from then-Rep. Brian Bilbray (R-CA) would have essentially cut the tax rate on repatriated earnings to zero.[6] Senator John McCain (R-AZ) recently proposed a repatriation holiday that would allow a tax rate of between 5.75 and 8.85 percent on repatriations.[7] Another proposal from Rep. John Delaney (D-MD) and Senators Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Roy Blunt (R-MO) would set the reduced holiday tax rate through a complicated auction mechanism that would generate many of the same problems of a more straightforward repatriation tax holiday (see Box 1). Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) and Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) have also suggested repatriation tax holidays to produce revenues for the Highway Trust Fund.[8] (See Box 2.)

Some policymakers propose to use the revenues from a repatriation tax holiday to “offset” the cost of preventing the Highway Trust Fund (which funds surface transportation) from becoming insolvent later this summer or to “finance” infrastructure spending some other way.[9] Politically, a repatriation holiday is a more appealing financing mechanism for lawmakers than, say, a proposal to address the shortfall in the Highway Trust Fund or otherwise finance infrastructure projects by raising the federal tax on gasoline. In reality, however, this “free lunch” approach doesn’t work — a repatriation tax holiday cannot truly “finance” anything because it loses revenue over the first decade and more revenue in decades after that, as the JCT’s cost estimate demonstrates.

Rep. John Delaney (D-MD) and Senators Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Roy Blunt (R-MO) have proposed legislation that would pair a repatriation tax holiday with an “infrastructure bank.”a While the proposal is complex, it would still generate the same fundamental problems that come with a repatriation tax holiday.

For starters, it would lose federal revenue. Multinationals would purchase bonds with a face value of $50 billion to capitalize an infrastructure bank. The bonds, however, would be worth much less than $50 billion because the bill requires that they return a very low 1 percent annual interest rate over a 50-year term. The Economic Policy Institute values them at $13 billion.b

Corporations would find it worthwhile to purchase the bonds at a loss because each bond purchased would allow them to repatriate a certain amount of foreign profit entirely free of tax. The exact amount of tax-free repatriation per bond would be determined by auction: companies would bid how much they would get to repatriate tax-free per dollar of infrastructure bonds purchased, with the lowest bids winning. Tax-free repatriations would be capped at $6 for each $1 of bond purchased.

Theoretically, a rudimentary estimate of the revenue loss from this channel could range between $70 billion to $105 billion (a 35 percent corporate tax rate forgone on tax-free repatriations of $200 billion to $300 billion).c The reality is, of course, far more complicated. Multinationals may not have brought back all of that money anyway in the next ten years and paid tax on it, reducing the potential revenue loss under repatriation. In addition, the proposal would encourage multinationals to shift more profits overseas in anticipation of more tax holidays in the future, thus making the potential long-term revenue loss greater.

Just like a straightforward repatriation tax holiday, the proposal would give the biggest rewards to the multinationals that have most aggressively shifted profits offshore — and, as just noted, encourage these and other companies to shift even more profits and investment overseas in coming years in anticipation of more tax holidays.

aH.R. 2084: “Partnership to Build America Act of 2013” and S. 1957: “Partnership to Build America Act of 2014.”

bThomas Hungerford, “How Not to Fund an Infrastructure Bank,” Economic Policy Institute, February 10, 2014, http://www.epi.org/publication/how-not-to-fund-an-infrastructure-bank/.

cIbid

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) has developed a revised version of a repatriation tax holiday that is paired with a provision to offset its costs so that on net it would raise $3 billion in revenue over ten years, according to press reports that quote his staff.a Senator Reid has not released this alternative or a Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) score of it. The limited details that have been reported suggest the proposal should be viewed with considerable skepticism.

Reports indicate there are two main reasons that this proposal could raise $3 billion in revenue over ten years, compared with the $96 billion cost, according to JCT, of repeating the 2004 repatriation tax holiday:b

- The proposal would set the holiday tax rate at 9.5 percent, which is higher than the 5.25 percent rate under the 2004 holiday. A repatriation holiday at a rate of 9.5 percent (a 73 percent discount on the usual 35 percent corporate rate) would certainly still carry a large cost, perhaps in the range of $50 billion over ten years.

- The proposal would couple the revenue-losing repatriation tax holiday with a provision that raises revenue — reportedly $3 billion more than the cost of the holiday over ten years. Only sparse details of this offset are available; some reports suggest that it would involve effectively limiting certain tax benefits related to borrowing by multinational corporations.

There are a series of concerns with this proposal.

First, the core of the proposal is still a costly repatriation tax holiday; the offset cited above is the sole component of the proposal that raises money. The repatriation tax holiday piece itself would still lose substantial revenue over ten years, and in later decades.

Second, because no JCT score of the proposal has been released, its long-term revenue impacts are unclear. Even if it raises $3 billion over ten years, it could add to deficits after the first decade. A repatriation tax holiday by itself would bleed revenues for decades to come, because it has the permanent effect of encouraging corporations to shift more profits and investment offshore. Unless the proposed offset fully offsets the cost of a repatriation holiday not only over the first decade but also in later decades, the overall proposal would add to deficits in those later decades.

For example, as with many other efforts to curb various tax-avoidance practices by multinationals, corporate lawyers and accountants may over time find ways around the offset, diluting the revenues it raises over time. In the absence of either the JCT score or details of the offset, it is difficult to know how robust it is and therefore how the package will affect long-run revenues.

Finally, if the $3 billion that the package raises over ten years were dedicated to the Highway Trust Fund, as some reports suggest it might be, it would keep that fund solvent for only a few months. Yet by allowing another repatriation tax holiday, the proposal would create expectations for future holidays and boost incentives for corporations to shift profits and investments overseas — a high price to pay for a plan that extends the Highway Trust Fund for a very short time.

Overall, the proposal should be viewed with skepticism. At its core, this alternative appears to simply pair a repatriation holiday with an offset. But offsets should not be used to pay for a costly tax cut for some of the largest multinationals that would reward and encourage aggressive tax avoidance in the future. Moreover, if policymakers enacted the reported offset on its own, rather than to cover the cost of a repatriation tax holiday, it could likely keep the Highway Trust Fund solvent for a few years rather than just a few months.

If and when a JCT score for the proposal becomes available, we will conduct and issue a fuller analysis of it.

a Brian Faler, “Harry Reid’s tax cut twofer roils Senate,” Politico, June 14, 2014, http://www.politico.com/story/2014/06/harry-reid-tax-cut-senate-107829.html#ixzz34jDr7nlu.

bIbid.

The JCT recently analyzed a repatriation holiday proposal (identical to the 2004 holiday) and found that while it would boost revenues over the first two years as companies rushed to repatriate the profits they held overseas to take advantage of the temporary very low tax rate, it would bleed revenues for years and decades after that (see Figure 1).

[10] Over the first decade, a repatriation holiday would cost

an estimated $96 billion. One reason why, the JCT explains, is that it would encourage companies to shift more profits and investments overseas in years to come in anticipation of more tax holidays, thus leaving those profits free from U.S. tax. In a more detailed analysis that JCT released of the same proposal in 2011, it noted that this was the biggest reason why another repatriation tax holiday would be so costly.

[11]

Large multinational corporations lobbying for the 2004 tax holiday claimed they would use the repatriated profits to expand operations in the United States, boosting capital spending, economic growth, and job creation. The 2004 act that authorized it stated that its goal was to “encourage the investment of foreign earnings within the United States for productive business investments and job creation.”[12]

These promises did not bear fruit. There is no evidence that the holiday had the promised beneficial effects, as researchers at academic institutions, the Congressional Research Service, the Treasury Department, and outside analysts all have found. To the contrary, there is strong evidence that firms used the repatriated earnings mainly to benefit corporate owners and shareholders and that the congressional restrictions on the use of repatriated earnings to ensure they were invested in the United States were ineffective.

To qualify for the 2004 tax holiday, corporations had to draft and follow a “dividend reinvestment plan” for reinvesting the repatriated cash in approved uses — including hiring and training U.S.-based workers, investing in U.S. infrastructure, conducting research and development, and providing marketing in the United States. The legislation, and subsequent IRS guidance, sought to bar firms from spending their repatriated earnings under the holiday on executive compensation, shareholder dividends, and stock buy-backs.

But, studies show, firms used these earnings not for productive new investments or jobs, but largely for the very purposes Congress had sought to prohibit such as paying out large amounts of cash to shareholders through share repurchases. The firms used the repatriated profits to pay for already budgeted expenses, thereby freeing up other money for stock buy-backs and other supposedly restricted activities. Legal restrictions on firms’ use of repatriated profits thus had little effect on how firms effectively spent the funds.

The repatriation holiday “did not increase domestic investment, employment, or [research and development],” according to a study by economists at the University of Illinois, Harvard University, and MIT.[13] Another study found that “firms enjoying disproportionately larger gains under the act were no more likely to spend repatriated funds on growth-generating activities than other firms.”[14] Even firms that lobbied for the tax holidaydid not use the funds as they had promised. “[R]epatriations in response to the holiday by firms that lobbied for the [repatriation tax holiday] did not significantly increase investment in the United States,” researchers found.[15]

Moreover, the top 15 repatriating corporations, which repatriated over $150 billion during the holiday, reduced their U.S. workforce by nearly 21,000 jobs between 2004 and 2007 even as they reaped large benefits from the tax holiday and passed them on to shareholders, a Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations report found.[16] Corporations that enjoyed the holiday but laid off American workers shortly thereafter included:

- Hewlett-Packard, which “announced a repatriation of $14.5 billion, layoffs of 14,500 workers, and stock buybacks of more than $4 billion for the first half of 2005 — about three times the size of its buybacks in the period a year earlier,” the New York Times reported;[17]

- Pfizer, which repatriated around $37 billion (the largest amount of any firm) shortly before eliminating approximately 10,000 American jobs and closing U.S. factories in 2005;[18]

- Ford Motor Company, which repatriated around $850 million under the holiday and then laid off more than 30,000 U.S. workers in 2005 and 2006;[19]

- Merck, which repatriated $15.9 billion and announced layoffs of 7,000 workers in 2005; and

- Honeywell International, which repatriated $2.7 billion and laid off 2,000 workers in 2005 and 2006.

These layoffs came at a time when the economy was growing significantly and adding jobs. As the Treasury Department noted, many of the largest beneficiaries of the tax holiday eliminated U.S. jobs in 2006 despite economy-wide job growth, using the repatriated funds (as noted above) to repurchase stock and pay dividends.[20]

Firms that shift income to foreign tax havens understand that they can defer U.S. corporate income tax as long as they leave their profits abroad, but they’ll have to pay tax if and when they repatriate the profits. Because they will likely have to repatriate some of the offshore profits at some point for business reasons, they are restrained at least to some extent from shifting investments merely to avoid taxes.

If, however, the President and Congress enact another tax holiday, rational corporate executives will very likely conclude that more tax holidays are coming down the road and will adjust their investment and tax strategies accordingly. They almost certainly will move more investment and jobs overseas and book more profits overseas and keep the profits there while they wait for another tax holiday, which would allow the bulk of these profits to face another sharply reduced tax rate when repatriated. This is precisely the reason why the recent JCT analysis of a repatriation tax holiday concluded:[21]

A second repatriation holiday may be interpreted by firms as a signal that such holidays will become a regular part of the tax system, thereby increasing the incentives to retain earnings overseas rather than repatriating those earnings and to locate more income and investment overseas.

In other words, the expectation of future tax holidays will make firms more inclined to shift income into tax havens and less likely to reinvest earnings in the United States — which is precisely the opposite of what repatriation promoters claim. As tax experts Lee Sheppard and Martin Sullivan have observed, “repatriation tax holidays have the effect of encouraging the very behaviors they were intended to reverse.”[22] That means less investment in the United States and, as explained above, lower tax revenues.

That occurred in the aftermath of the 2004 tax holiday. A study of U.S. multinationals that accounted for 79 percent of repatriations under the 2004 holiday found a “dramatic increase” after the holiday in the rate at which they increased their stockpile of foreign earnings.”[23] In each of the three years after the 2004 holiday, these companies added three times as much to the new profits they held overseas, on average, as they did in the each of the ten years before the holiday.[24]

Largely because a holiday would convince corporations to expect similar holidays in the future, Congress emphasized in 2004 that its repatriation holiday of that year should be a one-time-only tax break. “[T]his is a temporary economic stimulus measure,” the conference report accompanying the legislation stated, “and… there is no intent to make this measure permanent, or to ‘extend’ or enact it again in the future.”[25] Were Congress to break that promise and allow corporations to again repatriate accumulated foreign earnings at an extremely low rate, it would spur even more aggressive corporate use of overseas tax shelters. As Martin Sullivan has written, “Another repatriation holiday would remove the only significant restraint on them [U.S. multinational corporations] to move profits abroad. The dam would be broken.”[26]

Large multinationals claim they are cash-constrained and would make significant, job-creating investments in the United States if they had near-tax-free access to their foreign earnings. Their claim to be cash-constrained is dubious, however, given the large sums that many large multinationals are paying to buy back their own stock.

The ten companies with the largest stockpiles of foreign earnings in 2013 paid more than $107 billion in cash to shareholders that year through share repurchases, as Table 1 shows. Seven of them were among the ten companies with the largest share repurchases that year.

For example, Apple repatriated $755 million during the 2004 tax holiday and has lobbied for another one.[27] But, while the company has been stockpiling foreign profits (which totaled $132 billion at the end of Apple’s latest financial quarter), it instituted a plan in 2012 that will pay out $130 billion in cash to its shareholders through share repurchases and dividends by the end of 2015. As Apple’s chief financial officer put it, “We continue to generate cash in excess of our needs to operate the business, invest in our future, and maintain flexibility to take advantage of strategic opportunities” (emphasis added).[28] Rather than finance these payouts to shareholders by repatriating foreign profits and paying U.S. tax on them, Apple took advantage of what its executives called its access to “attractively priced capital” by issuing bonds: the company issued $17 billion of bonds in 2013 and plans to offer another $17 billion in 2014.

| 1. |

General Electric |

$110 |

$10 |

| 2. |

Microsoft Corp. |

$76 |

$6 |

| 3. |

Pfizer Inc. |

$69 |

$17 |

| 4. |

Merck & Co Inc. |

$57 |

$6 |

| 5. |

Apple Inc. |

$54 |

$27 |

| 6. |

International Business Machines |

$52 |

$14 |

| 7. |

Johnson & Johnson |

$51 |

$4 |

| 8. |

Cisco Systems |

$48 |

$8 |

| 9. |

Exxon Mobil Corp. |

$47 |

$16 |

| 10. |

Citigroup Inc. |

$44 |

* |

| |

|

|

|

| Total (These companies) |

$609 |

$107 |

| All companies |

$2,119 |

$478 |

| Top 10 companies’ share of total |

29% |

22% |

|

Highlight indicates company is in top ten |

Source of share buyback amounts: Microsoft’s 10-Q and 10-K filings, Johnson and Johnson’s 10-K filing, and FactSet for all other companies. Amounts are for calendar year 2013 or closest corresponding period available.

Source of offshore deferred earning amounts: Audit Analytics, using companies’ 10-K filings for their 2013 fiscal year.

*Citigroup planned to spend $6.4 billion on stock repurchases, but the Federal Reserve barred it from doing so due to insufficient improvement in the annual stress test of financial institutions. Source: Halah Tourylalai, “Stress Tests Round 2: Citi Fails Fed's Most Important Exam, 25 Banks Pass” March 26, 2014, Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/sites/halahtouryalai/2014/03/26/stress-tests-round-2-citi-fails-feds-most-important-exam-25-banks-pass/. |

Apple’s borrowing doesn’t reflect a shortage of cash on its part or support the view that it and other multinationals are cash-constrained. In fact, Apple’s borrowing proves just the opposite. Apple can borrow such large sums at extremely low rates because lenders know that, if it ever needs cash, it can bring back the huge sums that it has parked overseas. In part for that reason, Apple is no risky borrower for any potential lender. As Apple’s executives put it, they would “leverage [Apple’s] very strong balance sheet” to issue the bonds.

In addition, Apple executives have emphasized that they have had access to ample domestic cash to grow their business and make investments.[29] That strongly suggests that a new tax holiday would not generate a surge of Apple job-creating investments in the United States. More likely, Apple would use the repatriated cash to replace, at least in part, the firm’s reliance on bonds to finance payments to its shareholders.

Why are firms paying out cash to shareholders rather than investing their funds to create jobs? They are probably doing so because of inadequate demand for their goods and services and uncertainty about future increases in demand.[30] As the Washington Post reported last year,[31]

“Corporate profits are very high, but corporations are not expecting a huge burst of growth,” said Ben Inker, co-head of asset allocation at GMO, an investment-management firm. “Given that they’re not expecting a lot of growth, there isn’t a lot of reason to invest. So they’re finding ways of getting money back to shareholders.”

That’s one more reason why firms won’t likely use cash that’s repatriated under a tax holiday for substantial new investment.[32]

Finally, to the extent that firms are cash-constrained, the Congressional Research Service has found that the problem applies mainly to small firms. Yet small firms stand to benefit far less from a repatriation tax holiday — and to account for a far smaller share of the repatriated dollars under a holiday — than large multinational corporations.[33] Moreover, purely domestic corporations (i.e., those without foreign operations) would not benefit at all from another repatriation holiday.

Proponents of a repatriation tax holiday often argue that foreign profits are “trapped” offshore so a repatriation tax holiday is needed to put those profits to work in the U.S. economy.a However, as former Joint Tax Committee Chief of Staff Edward Kleinbardb and other analysts have explained, a large share of those profits are already being used directly or indirectly in the economy — and what is “trapped” is largely the U.S. taxes due on them.

Multinationals can defer paying U.S. tax on their foreign subsidiaries’ earnings by declaring them “permanently reinvested” offshore. But that’s an accounting illusion: companies can declare earnings “permanently reinvested” even if their subsidiaries park those earnings in U.S. banks, hold them in U.S. dollars, or invest them in U.S. Treasury bonds or U.S. corporate securities.

Multinationals do not routinely disclose how their subsidiaries invest their cash holdings. However:

- A 2010 survey of 27 large U.S. multinationals found that nearly half of their “overseas” tax-deferred corporate profits were invested in U.S. assets, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations found. These assets included U.S. dollars deposited in U.S. banks or invested in U.S. Treasury bonds or other U.S. government securities, securities and bonds issued by U.S. corporations, and U.S. mutual funds and stocks.c

- A 2013 Wall Street Journal report found that Google, Microsoft, and the data-storage firm EMC Corp. kept more than three-quarters of their foreign subsidiaries’ cash in U.S. dollars or U.S. dollar-denominated securities.d

The offshore money shows up in the economy in other ways as well. To be sure, the multinational itself cannot use money that its foreign subsidiaries have parked in U.S. dollars or assets to directly fund U.S. operations or for shareholder payouts unless it pays U.S. tax on it. But, because dollars are fungible, a firm can indirectly use those profits to fund U.S. activities.

For instance, companies that have large stashes of cash offshore are generally considered as low-risk borrowers, in part because they can always repatriate their offshore cash (and pay the deferred taxes) to meet their loan obligations. So even though companies designate these funds as “permanently reinvested” offshore, they can use them to borrow at cheaper rates and then use the borrowed funds to finance their U.S. activities, including share repurchases.

a See, for example, Kate Linebaugh, “Top U.S. Firms Are Cash-Rich Abroad, Cash-Poor at Home,” Wall Street Journal, Updated Dec. 4, 2012.

b Testimony of Professor Edward Kleinbard, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means hearing on “Tax Reform: Tax Havens, Base Erosion, and Profit-Shifting,” June 13, 2013, http://www.tcf.org/assets/downloads/2013-06-13-tax-reform-tax-havens-base-erosion-and-profit-shifting.pdf.

c “Offshore Funds Located Onshore,” United States Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Majority Staff Report Addendum, December 14, 2011, http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/report-addendum_-psi-majority-staff-report-offshore-funds-located-onshore. d Kate Linebaugh, “Firms Keep Stockpiles of 'Foreign' Cash in U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, January 22, 2013, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887323301104578255663224471212#printMode.

Many companies have so much of their cash overseas because they have arranged their finances to show a large share of their profits originating in low-tax countries. For instance, they transfer patents or other intellectual property (which is very difficult for tax authorities to value accurately) to foreign subsidiaries in those countries.[34] Technology and pharmaceutical companies have been particularly aggressive in shifting income abroad because they rely on intellectual property that they can shift relatively easily to other countries.

In fact, IRS data show that pharmaceutical and technology companies accounted for half of the repatriations that received the tax break under the 2004 holiday. There is no reason to believe that large pharmaceutical and technology companies, in particular, need a tax holiday — that they are somehow having more trouble obtaining cash than other multinationals or smaller firms. Nor is there any compelling reason why they deserve an additional, highly lucrative tax break from a new repatriation holiday.

Some tax reform proposals, such as those from President Obama and House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp, could require multinationals to pay U.S. taxes on their current stock of profits held overseas as part of a transition to a new U.S. corporate tax system.[35] Such a one-time tax is not the same as a repatriation tax holiday and, if designed correctly, could offer real benefits.

First, a transition tax would be compulsory. Multinationals would have to pay U.S. taxes on those foreign profits whether they repatriate them or not (though companies could pay that tax over a period of time). By contrast, under a repatriation tax holiday, companies could choose whether to repatriate their earnings and, to incentivize companies to do so, the tax rate would be set extremely low.

Second, a transition tax would be coupled with reforms that reduce or eliminate the incentive for companies to continue deferring their repatriation of foreign profits. By contrast, the 2004 repatriation tax holiday lacked such reforms, and it strongly encouraged firms to stockpile profits offshore in subsequent years in the hope of another tax holiday.

In enacting a transition tax, policymakers would need to make sure that the tax rate on that transition tax was close to the current U.S. tax rate; a much lower rate would confer a large windfall reward on multinationals that had aggressively shifted profits offshore. In addition, the new tax system as a whole would need to substantially shrink incentives for corporations to shift profits and investment offshore in the future.[36] A transition tax that met those requirements could represent sound policy that would raise tax revenue, rather than draining it.

Moreover, policymakers could use those transitional revenues for investments for one or several years, such as for infrastructure spending or debt reduction — rather than for permanent corporate rate cuts that increase deficits and debt for decades to come, long after the temporary revenue increase from a transition tax has ended.[37]