Rental assistance helps more than 340,000 veterans — the great majority of them poor or near poor — afford decent housing. It appears to have played a central role in the 33 percent reduction in veterans’ homelessness between 2010 and 2014, and it allows recipients to devote more of their limited resources to other basic needs, like food or medicine. But it reaches only a fraction of veterans in need; many veterans continue to experience homelessness or pay very high shares of their income for housing.

Policymakers can address veterans’ housing needs more adequately by not only protecting funding for rental assistance programs such as Housing Choice Vouchers and public housing but also expanding housing assistance for the most vulnerable low-income people. The latter could include providing funds for the National Housing Trust Fund through housing finance reform legislation and establishing a low-income renters’ tax credit as part of tax reform.

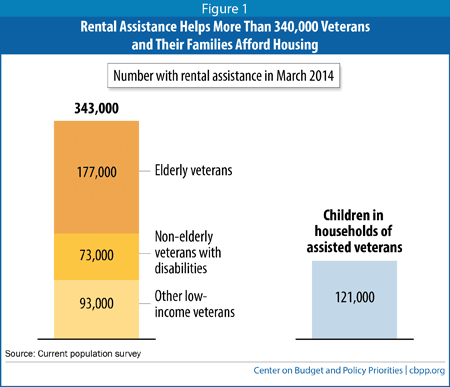

Rental assistance helped 343,000 veterans afford housing in March 2014, the most recent data available. (See Figure 1.) Some 52 percent were elderly and 21 percent were non-elderly veterans with disabilities. Some 121,000 children lived in assisted families that included a veteran.[1] Ten percent of veterans with rental assistance were female.

The HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing voucher program (HUD-VASH), a component of the Housing Choice Voucher program that primarily targets chronically homeless veterans with disabilities (in combination with case management and clinical services through VA medical centers), assists close to 50,000 veterans.

[2] The nearly 300,000 remaining assisted veterans were served through other federal, state, and local programs, which for the most part are “mainstream” programs not specifically targeted on veterans. Most of these veterans likely participated in the three main federal rental assistance programs: Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance, and public housing.

[3] Participants in these programs generally pay 30 percent of their income toward rent for a modest housing unit; rental assistance covers the rest.

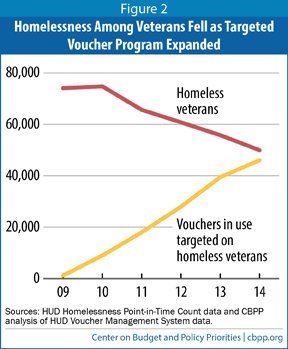

Rental assistance has been central to efforts to reduce homelessness among veterans, which have made considerable progress in recent years. Studies have found that rental assistance sharply reduces homelessness, which suggests that a significant share of the 343,000 assisted veterans may have been homeless without assistance.[4] Also, studies that looked specifically at the HUD-VASH program found that veterans with psychiatric or substance abuse disorders who received supportive housing vouchers spent less time homeless than similar veterans who received other forms of treatment but did not get these vouchers.[5]

Since 2008, Congress has funded steady increases in the number of HUD-VASH vouchers. As Figure 2 shows, the share of veterans who are homeless fell by 33 percent over roughly the same period. The departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Housing and Urban Development (HUD) implemented other homelessness initiatives during these years, and it is difficult to determine how much of the decline in homelessness among veterans stemmed from any particular factor. But the added rental assistance provided through the HUD-VASH program likely played a major role.

In addition to reducing homelessness, rental assistance eases hardship for veterans by freeing up resources for other basic needs (such as food or health care) and reducing housing instability and crowding, which can have long-term effects on education and health.

[6] Most assisted veterans are poor or near poor and would struggle to make ends meet without assistance. In March 2014, 34 percent of assisted veterans lived in households with incomes below the poverty line, which was $12,119 for a single person under age 65. Seventy-six percent of assisted veterans lived in households below 200 percent of the poverty line.

[7]In 2009, the Obama Administration set a goal of ending homelessness among veterans by 2015.[8] Despite progress in recent years, this goal remains far off. A HUD assessment on one night in January 2014 counted 49,900 homeless veterans: 17,900 sleeping in the street, in cars, or in other places not meant for human habitation, and 32,000 in emergency shelters, transitional housing, or similar arrangements.[9] Many more veterans experience homelessness over the course of a year than at any point in time. During 2012, the most recent year for which complete data are available, 138,000 veterans stayed in a shelter for at least one night.[10]

Moreover, many veterans who are not homeless nevertheless struggle to afford housing. In 2012, some 1.79 million low-income veterans lived in households that paid more than 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities, and 762,000 lived in households that paid more than 50 percent.[11] Government programs and the private sector widely regard housing as unaffordable if it costs more than 30 percent of a household’s income. Families that pay substantially more often must divert funds away from other basic needs. They also are at greater risk of having to move frequently, entering into stressful and insecure arrangements such as doubling up with friends and family or becoming homeless.

To address veterans’ unmet housing needs, policymakers will need to expand rental assistance. This should include continued expansion of the HUD-VASH program. But many needy veterans do not qualify for HUD-VASH (which is generally available only to veterans who served for at least 24 months and received particular types of military discharges) or do not require the supportive housing HUD-VASH provides. As a result, policymakers also need to adequately fund the mainstream rental assistance programs that help most assisted veterans.

Unfortunately, rental assistance funding is under considerable pressure. Cuts in 2013 voucher funding resulting from “sequestration” have compelled state and local agencies to serve fewer low-income families, and policymakers only partially restored these cuts in 2014. Recent cuts also have sharply reduced funding for maintaining and renovating public housing. This could expose low-income veterans in public housing to lack of heat, faulty elevators, or other uncomfortable or unsafe conditions. Over time, repeated deferral of needed maintenance could cause developments to deteriorate to the point where they are no longer habitable and must be demolished or sold, leaving fewer units available for veterans and other low-income people. Also, tight funding for the Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance program could discourage private owners of assisted units from renewing their subsidy contracts, shrinking the number of veterans assisted through that program.

Even if policymakers reverse recent rental assistance cuts and avoid new ones, the 2011 Budget Control Act’s long-term caps on overall domestic appropriations will continue to make it difficult to significantly expand existing rental assistance programs. Other measures will be needed to help address unmet needs among veterans.

One step would be to set aside some fees generated through reform of the housing finance system to fund the National Housing Trust Fund, which Congress authorized in 2008 to develop and rehabilitate housing affordable to the lowest-income families but which has never received funding. The Senate Banking Committee passed a housing finance reform bill in May 2014 that would provide substantial resources for the trust fund.

In addition, if tax reform legislation advances, Congress could use a portion of savings from reforming homeownership or other tax expenditures to create a new, state-administered renters’ tax credit to help some of the neediest families afford housing. If such a credit were capped at $5 billion annually and states allocated credits to veterans in proportion to their share of the eligible population, some 84,000 veterans would receive assistance.[12] If states targeted larger shares of their credits on veterans, they would be able to assist most veterans who struggle to afford housing today.

Rental assistance has played an essential role in recent years in reducing homelessness among veterans. But much remains to be done if the nation is to end homelessness among veterans and to reduce the number of veterans who pay high shares of their income for rent. Congress could advance those goals by continuing to expand the HUD-VASH program, reversing recent cuts in rental assistance, and taking measures such as funding the National Housing Trust Fund and establishing a new renters’ tax credit to assist veterans and other vulnerable low-income people.