When families are able to meet basic needs such as food, housing, and medical care, parents and other caregivers[2] experience less stress, which allows them to provide the critical support that children need to grow into healthy, productive adults. This is a key finding from our analysis of data from the RAPID-EC survey, which we conducted during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic to assess the well-being of families with children under age 5. This finding is consistent with findings from a growing body of scientific research on the impact of adversity on children’s long-term outcomes.

Families with young children have been particularly affected by the pandemic, as parents/caregivers have been forced to figure out ways to meet their families’ most basic needs despite job insecurity, income loss, acute concerns about health and safety, and widespread closures of schools, child care centers, and many other services and resources typically available to support young children and their families. As bad as the situation has been, it would have been far worse without government assistance. Between 2019 and 2020 child poverty actually fell by 2.6 percentage points (using the Supplemental Poverty Measure); without government assistance, it would have risen by 2.8 percentage points.

The hardship caused by the pandemic has been deep and widespread, but for many families — especially Black and Latinx families, who have long had unequal opportunities due to racial discrimination, and families caring for a child with a disability, who face unique challenges due to their child’s special needs — hardship did not begin with the pandemic and will not end with it. To improve child well-being over the long run, we need to recognize the interconnectedness of many of the issues that families with children face and design federal and state policies that help them address those issues. We need to make sure families can meet their basic needs while we simultaneously fix our broken child care system so that more parents can return to the labor market. We also need to make sure that child care providers and parents/caregivers have access to adequate mental health services to address the trauma they have experienced during the pandemic. And we need to address structural inequities to provide greater income and stability for Black and Latinx mothers. Young children are incredibly resilient and their brains are excellent at adapting to change. Our task is to create the conditions that will allow them to thrive as we come out of the pandemic.

The RAPID-EC project is a national survey of early childhood family well-being designed to gather ongoing, high-frequency data about the experiences of families with young children during the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. This report discusses the following key findings from the RAPID-EC survey data collected during the first year of the pandemic:

- Material hardship (i.e., the inability to afford basic needs) has been widespread among households with young children since the pandemic began. This is especially true for households that have historically experienced inequities based on race/ethnicity, family structure (i.e., single-parent households), or other factors (e.g., households in which a child has a disability).

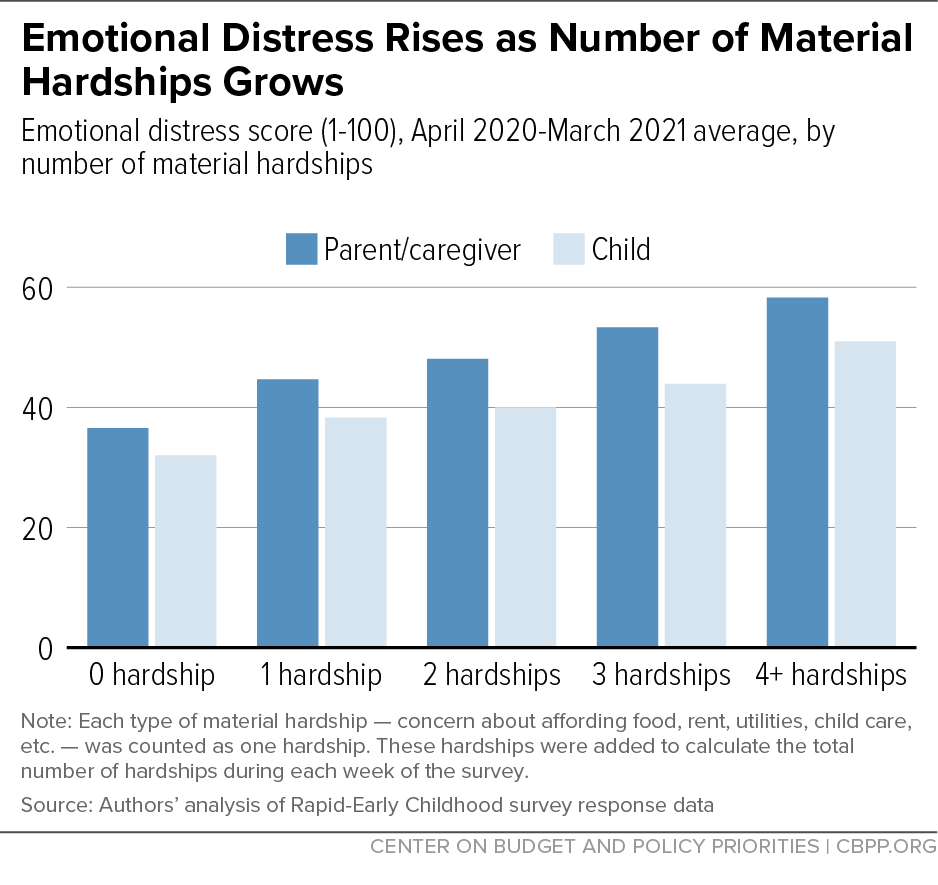

- Emotional distress among both parents/caregivers and their children is higher in families facing more material hardship. When caregivers can’t meet their family’s basic needs, their emotional distress increases. This leaves them less able to protect their children from the consequences of adversity in the household, and their children’s emotional distress also increases. Parents and children experiencing four or more hardships reported 60 percent greater distress (based on a composite score developed using data from the survey) than parents and children experiencing no hardships.

- Hardship goes down and the emotional well-being of both caregivers and their children improves when families are given resources to meet their basic needs. Financial support and emotional support give parents and caregivers more resources to protect their children from high levels of stress. The survey data show that financial relief from the government allowed families with young children to immediately afford basic essentials and pay their bills, which reduced the emotional burden of ongoing financial challenges associated with the pandemic.

The RAPID-EC survey is an ongoing survey of U.S. families with children aged 5 or younger. This report includes data from one year of RAPID-EC survey data collected online, at weekly intervals (54 surveys total), from 5,336 parents and other caregivers between April 6, 2020, and March 20, 2021. Participants included a nationally representative sample of households from all 50 states. Parents and caregivers were diverse in term of race/ethnicity (7 percent were non-Latinx Black, almost 13 percent were Latinx) and income (28 percent were at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty line based on their self-reported 2019 income).

Material hardship was evaluated weekly by asking families to indicate whether they were having difficulty paying for basic needs in one or more of the following categories: food, housing (mortgage or rent), utilities, child care, medical care, social support, emotional support, and “other.” Emotional distress was measured in parents/caregivers as a composite score based on self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness (on a 1–100 scale), and in children as a composite score based on parent/caregiver-reported fearfulness/anxiety and fussiness/defiance (also on a 1–100 scale).

The RAPID-EC website (https://www.uorapidresponse.com/) includes frequent updates and weekly reports of new data.

Decades of scientific research show that experiences in the early years of a child’s life affect brain development and biology. Childhood is a time of rapid growth and change in many neurobiological and psychological systems, as the body and brain learn to respond effectively to the surrounding environment. The body’s adaptation to transitory stress or occasional threats to safety is a helpful and necessary part of development; however, the body’s response to prolonged, severe stress can have lifelong negative consequences.

When adversity during early life is frequent, prolonged, or particularly acute, it can create “toxic stress,” which means the stress may permanently affect the developing brain and related biological systems.[3] When children face significant threats to their health and well-being on an ongoing basis, their brains and bodies may adapt to mitigate or avoid these threats. For example, they may develop hypervigilant sensory processing and heightened physical responses to help them recognize and defend against potentially threatening situations; or conversely, they may become desensitized and less responsive to the environment. The longer these threats continue, the more significant these biological changes may become.

The changes in the brain and body that result from toxic stress can be adaptive in the short term (e.g., by facilitating the body’s “fight or flight” response to imminent danger). However, the accumulation of heightened physiological and emotional responsiveness has significant negative effects over time. Specifically, these biological changes increase long-term risk for emotional and mental health disorders, learning difficulties, and lifelong health problems such as obesity and heart disease.[4] Moreover, the body’s adaptive responses to stress and adversity in early childhood are thought to contribute to nearly half (45 percent) of childhood mental health disorders and nearly one-third (30 percent) of mental health disorders in adulthood.[5]

Fortunately, science has long shown that nurturing relationships with parents and other significant adults in children’s’ lives can prevent toxic stress from occurring in the face of childhood adversity. Indeed, caring family relationships represent one of the most stable and consistent contributors to childhood resilience.[6] However, parents’ and other caregivers’ ability to mitigate toxic stress can be compromised when they themselves are under excessive stress. Many parents and other caregivers of young children have faced significant financial and emotional stress since long before the pandemic began, and even moderate stress that is not “toxic” (i.e., does not permanently change biological systems) may negatively affect children’s learning and emotional development. (A related CBPP paper discusses the significant struggles that U.S. families were already facing prior to the pandemic.)[7]

The pandemic has exacerbated these problems, causing significant stress for families through both direct financial challenges (e.g., job loss and inability to work) and related difficulties that can aggravate these challenges (e.g., lack of quality child care, limited access to school-based food and services, and less support from family and friends due to sheltering in place).[8] These pandemic-related hardships have had cumulative effects on mental health, with worse health outcomes observed in families experiencing more hardships.[9]

Helping families meet their basic needs can meaningfully reduce household adversity and improve both parents’/caregivers’ and children’s well-being. Reducing families’ financial difficulties leaves parents and other caregivers less stressed themselves and better able to protect their children from the stresses of the pandemic. Financial relief provides more resources for parents to meet their children’s basic physical needs and may result in increased emotional resources to provide a nurturing, secure home environment.

Using data from the ongoing RAPID-EC survey, we observe how daily hardship and emotional distress have increased in families with young children since the pandemic began. We also show how mitigation of hardship improves outcomes for both parents and children. (See box, “Introduction to the RAPID-EC Survey,” for details on the survey and a link to emerging data.)

Pandemic Increased Adversity, Reduced Parents’ Ability to Ameliorate It

Data from the RAPID-EC survey provides evidence that adversity resulting from the pandemic has affected many parents’ ability to buffer the negative impacts of the crisis on their children. Using these survey data, we assessed the impact of the pandemic on families’ experiences of financial difficulties and related emotional challenges through weekly measurement of material hardship (by asking parents and other caregivers whether they were having difficulty paying for basic needs like food, rent/mortgage, utilities, child care, etc.) and emotional distress (a composite score that captures depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness for parents and other caregivers and a composite score that captures fearfulness/anxiety and fussiness/defiance for children).

Every week during the first year of the pandemic, at least 1 in 4 households with young children were experiencing material hardship (difficulty paying for basic needs). At many times during the fall and winter of 2020, more than 1 in 3 were. These high rates of unmet basic needs are particularly concerning given the extent to which economic hardship negatively affects parents’ well-being and responsive caregiving, which in turn harms children’s mental and physical health. (While these data do not capture the substantial share of parents experiencing material hardship prior to the pandemic, the majority of parents in our survey responded that their situations worsened after the pandemic began.)

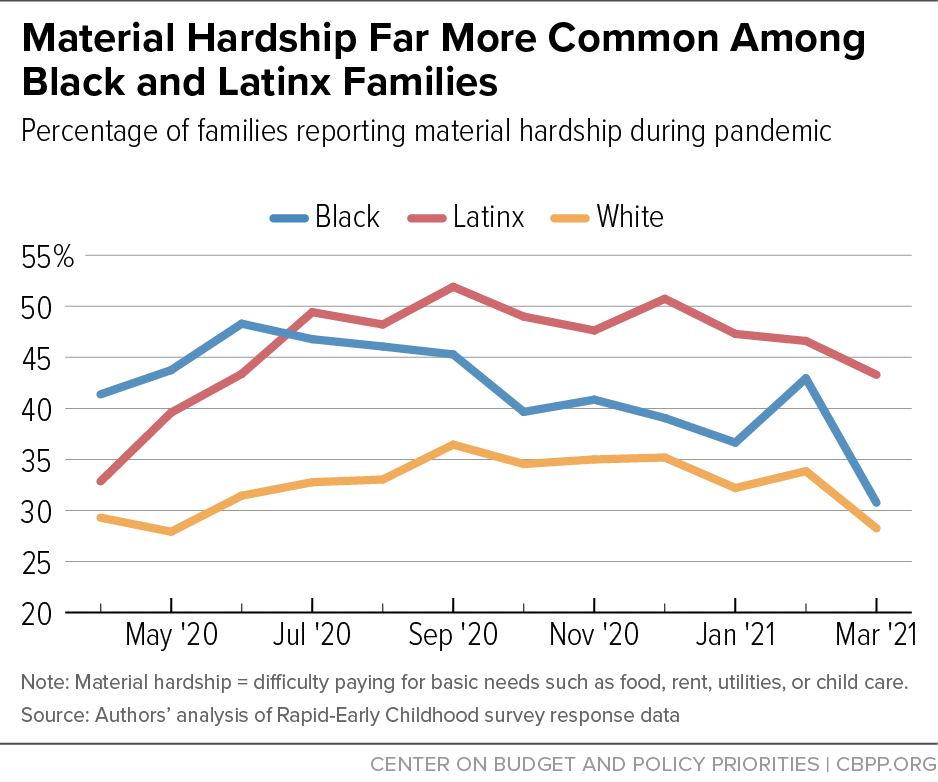

For Black and Latinx households, the first year of the pandemic was especially challenging. Black and Latinx families experienced significantly higher rates of material hardship than white families, with parents and other caregivers reporting difficulty paying for basic needs at rates nearly twice that of white households during many weeks of the survey. (See Figure 1.) These findings cannot be attributed to income level alone — even among middle- and upper-income families (those with incomes over 150 percent of the federal poverty line), a larger share of Black and Latinx households had difficulty paying for basic needs compared with white families at the same income levels.[10] The data are consistent with long-standing structural inequities based on race and ethnicity, which were well documented prior to the pandemic,[11] and which left Black and Latinx households with fewer assets to fall back on when their incomes fell, on average.

Due to racial income and wealth gaps, families of color were at a significant disadvantage when facing the financial challenges of the pandemic. Recent media reports also indicate that the pandemic has disproportionately affected people of color in almost every area of daily life. Black and Latinx parents/caregivers have lost jobs during the pandemic at a higher rate[12] than white parents/caregivers, and children in Black and Latinx households have experienced lower-quality distance learning and are more likely not to be in school.[13] Black and Latinx people are also becoming sick and dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than white people.[14] Overall, the pandemic appears to be exacerbating long-standing structural inequities based on race and ethnicity. In addition, since exposure to racism is itself a toxic stressor in children,[15] the combination of racism and related inequities in material hardship can have a compound negative impact on families of color.[16]

Emotional Distress Among Parents/Caregivers and Children Rises With Material Hardship

The widespread material hardship experienced by families of young children is particularly concerning because of a link in the RAPID-EC data between material hardship and emotional distress among parents/caregivers and their children. Higher levels of material hardship were associated with higher levels of emotional distress among parents and other caregivers, which were then associated with higher levels of emotional distress among children. (See Figure 2.) Notably, the timing of these findings supports a negative chain reaction in which material hardship in any given week was associated with increased caregiver distress in subsequent weeks, and this caregiver distress was, in turn, associated with increased child distress in the weeks that followed. It is also worth noting that emotional distress was high among all families, including those who did not report any hardships.

These data suggest that financial difficulties resulting from the pandemic have left parents worse off in terms of their own emotional well-being and of their ability to buffer their children from the many stressors — both financial and emotional — that families are facing as the pandemic continues. These data are consistent with other reports showing that family levels of anxiety and depression have fluctuated in time with pandemic-related material hardship, particularly in households with children.[17] Because the pandemic is leaving so many parents without the resources typically available to them to buffer their children from stress (e.g., meeting basic needs, providing a safe space with nurturing caregiving), they are less able to protect their children from the long-term negative consequences of pandemic-related hardships.

Similar to Black and Latinx households, RAPID-EC families in which a young child has special needs experienced material hardship at a higher rate (51 percent) than other households (38 percent) during the first year of the pandemic. Rates of emotional distress among both parents/caregivers and children in these families were also consistently higher during this time.

Health care disparities were also evident: 50 percent of special-needs children missed a well-baby or well-child visit during the pandemic, compared to 39 percent of other children, and children with special needs were significantly more likely to miss routine vaccinations. This is especially concerning for these families, given that these early preventative visits help ensure consistent monitoring of developmental progress and appropriate referrals for early intervention services.

Even prior to the pandemic, families who have a child with special needs experienced clear economic and social disparities.a During the last year and a half, these families have faced additional challenges: limited access to services (particularly those requiring in-person participation), lack of reliable child care (particularly with staff trained in caregiving for special-needs children), and income loss (which can be especially harmful given the higher expenses associated with caring for a child with special needs). Given the size of this subgroup (approximately 8 percent of all U.S. children under age 5 have a disability as defined in federal law),b challenges specific to this subgroup warrant greater attention as the pandemic continues and eventually wanes.

As the country continues to move toward a post-pandemic future and educational settings and other child services reopen, it will be essential to address the urgent needs of these families. Many have had very limited (or no) support or services since early 2020, which has left their special-needs children at an even greater disadvantage than before the pandemic. Parents/caregivers of children with special needs will also need extra support themselves to address the extreme, chronic stress that they have experienced during the last year and a half. Finally, an enhanced focus on early detection will be needed to identify children whose special needs might have been missed due to lack of in-person time with teachers, health care workers, and other care providers who would typically provide a first line of defense in identifying children in need of extra services.

a KidsData, “Children with Special Care Needs,” Population Reference Bureau, https://www.kidsdata.org/topic#cat=12,15.

b Merle McPherson et al., “A New Definition of Children with Special Health Care Needs,” Pediatrics, Vol. 102, No. 1, July 1998, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.102.1.137.

Increases in material hardship negatively affect parents’/caregivers’ and children’s well-being, but this cascade can be stopped and reversed when families with young children have the support they need. Survey data indicate that both emotional and financial support can interrupt the negative effects of material hardship.

Emotional support: Families who reported receiving higher levels of emotional support during the pandemic also reported higher levels of emotional well-being. These parents/caregivers and their children maintained lower levels of emotional distress even during weeks when material hardship was higher.

Financial support: Over 80 percent of families with young children received pandemic-related cash assistance (Economic Impact Payments or unemployment benefits) to help them meet their basic needs during the early months of 2021. While families with young children reported high rates of material hardship during the winter of 2020, hardship significantly decreased following arrival of the Economic Impact Payments in early 2021 (see Figure 1); and this decline was followed by reduced emotional distress in parents/caregivers and their children in subsequent weeks (not shown). Data also show that the majority of families who received pandemic-related cash assistance (62 percent who received Economic Impact Payments and 72 percent who received pandemic unemployment benefits), including high-income families, spent it on basic needs;[18] and 86 percent of families used Economic Impact Payments to pay overdue or unpaid bills.[19] Financial relief from the government allowed families with young children to immediately afford basic essentials and pay their bills, which reduced the emotional burden of ongoing financial challenges associated with the pandemic.

A recent analysis of data from the Census Bureau further substantiates the efficacy of the government’s pandemic relief measures.[20] In households with children (who received the largest stimulus benefits), food insufficiency dropped by 42 percent from January to April 2021, and rates of acute anxiety and depression dropped by 20 percent. When families are able to meet their basic needs, the emotional well-being of the entire household improves.

The devastating impacts of the last year and half on families with young children will continue to linger as society grapples with safe returns to in-person work and school, emerging coronavirus variants, and waning vaccine immunity over time. The effects of even a short period of toxic stress on young children are clear,[21] and immediate aid for families will help parents and other caregivers emerge from the ongoing financial hardships left in the pandemic’s wake and protect their young children from the long-term physical and emotional consequences that follow periods of acute stress.

In the RAPID-EC survey, we see that government relief measures work. Parents and other caregivers of young children, who have been experiencing considerable hardship and emotional distress since the pandemic began, spent their stimulus and unemployment money primarily on basic needs for their families. With the government’s help, families were able to address some of their most immediate financial challenges and protect their young children from the toxic stress that comes with ongoing hardship.

We need to take what we learned during the pandemic to reduce hardship and continue to help families meet their basic needs over the long term. Policies currently being considered by Congress would go a long way toward reducing adversity and providing the resources that parents need to provide a protective environment for their children. Making the Child Tax Credit available to all families would meaningfully reduce child poverty and would make the biggest difference for Black and Latinx families, who have been experiencing the greatest hardship during the pandemic and have historically had substantially higher rates of poverty due to structural inequities. Providing additional benefits to families to help them cover the costs of food would reduce hunger — one of the most prevalent hardships faced by families struggling to make ends meet. Housing assistance would reduce the high levels of disruptions, stress, and hardship that families face when they can’t pay the rent or don’t have a stable place to live. Finally, rebuilding our child care system is a necessity; without it parents will not be able to go back to work.