Kansas Provides Compelling Evidence of Failure of "Supply-Side" Tax Cuts

End Notes

[1] Scott Rothschild, “Task Force Working in Secret on Tax Proposal,” Lawrence Journal World, October 9, 2011.

[2] This claim has been thoroughly debunked. See, for example, Carl Davis, “Trickle-Down Dries Up,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 2017, https://itep.org/trickle-down-dries-up/. See also “ALEC’s Rich States, Poor States,” http://www.gradingstates.org/alecs-rich-states-poor-states/.

[3] “The Brownback Pro-Growth Plan: Making the State Income Tax Flatter, Fairer, and Simpler,” January 12, 2012, http://www.kslegislature.org/li_2012/b2011_12/committees/misc/ctte_s_assess_tax_1_20120112_01_other.pdf. The document included a table of “Data Compiled by Laffer Associates” comparing the recent economic performance of the non-income-tax states and the nine states with the highest top income tax rates.

[4] Pass-through income is taxable in the year in which it is earned even if it is not distributed to the owner. In other words, the income is “passed through” to the owner for tax purposes, but it may or may not be “passed through” in the form of cash.

[5] Brownback also proposed to double the standard deduction for heads of households to mitigate the increase in their tax liability resulting from his proposal to repeal the state earned income tax credit.

[6] Supplemental Note on Senate Substitute for House Bill 2117; http://kslegislature.org/li_2012/b2011_12/measures/documents/summary_hb_2117_2012.pdf. Governor Brownback signed House Bill 2117 into law on May 22, 2012.

[7] See the Fiscal Note on Senate Bill 78 as introduced, http://kslegislature.org/li_2014/b2013_14/measures/documents/fisc_note_sb78_00_0000.pdf.

[8] Supplemental Note on House Bill 2059; http://kslegislature.org/li_2014/b2013_14/measures/documents/summary_hb_2059_2013.pdf.

[9] Kansas Department of Revenue, Notice 15-06, https://www.ksrevenue.org/taxnotices/notice15-06.pdf; Notice 15-02, https://www.ksrevenue.org/taxnotices/notice15-02.pdf.

[10] “The Brownback Pro-Growth Plan.”

[11] This argument is not valid in the case of tax cuts for wage, salary, and passive investment income. Because states must balance their budgets, every dollar of such a tax cut must be offset by either reduced state spending (which takes a dollar of disposable income from a state employee, state contractor, or recipient of a state transfer payment) or an offsetting increase in another tax (which reduces the disposable income of the person paying it). The only exception to this is if the tax cut leads to dissaving by the state government, for example, the drawing down of state reserves or the delaying of a contribution to a state pension fund.

Putting more money into a business’s hands by cutting its taxes can lead it to make an in-state investment that it otherwise would not have made, assuming it lacks sufficient cash on hand to make the investment and cannot borrow the money.

[12] Arthur Laffer, Jonathan Small, and Wayne Winegarden, “Economics 101,” February 2012, published by the Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs.

[13] “A key part of the nine-state comparisons is that people and businesses move to states with pro-growth tax environments.” (“Economics 101,” p. 7.)

[14] Scott Rothschild, “Brownback Gets Heat for ‘Real Live Experiment’ Comment on Tax Cuts,” Lawrence Journal-World, June 19, 2012. Supply-side theory predicts positive impacts on state and national economic performance from cuts in a wide array of taxes, including corporate income and estate taxes.

[15] For an explanation of why cutting personal income taxes for businesses should not be expected to have significant supply-side effects in the real world, see: Michael Mazerov, “Cutting State Personal Income Taxes Won’t Help Small Businesses Create Jobs and May Harm State Economies,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 19, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2-19-13sfp.pdf.

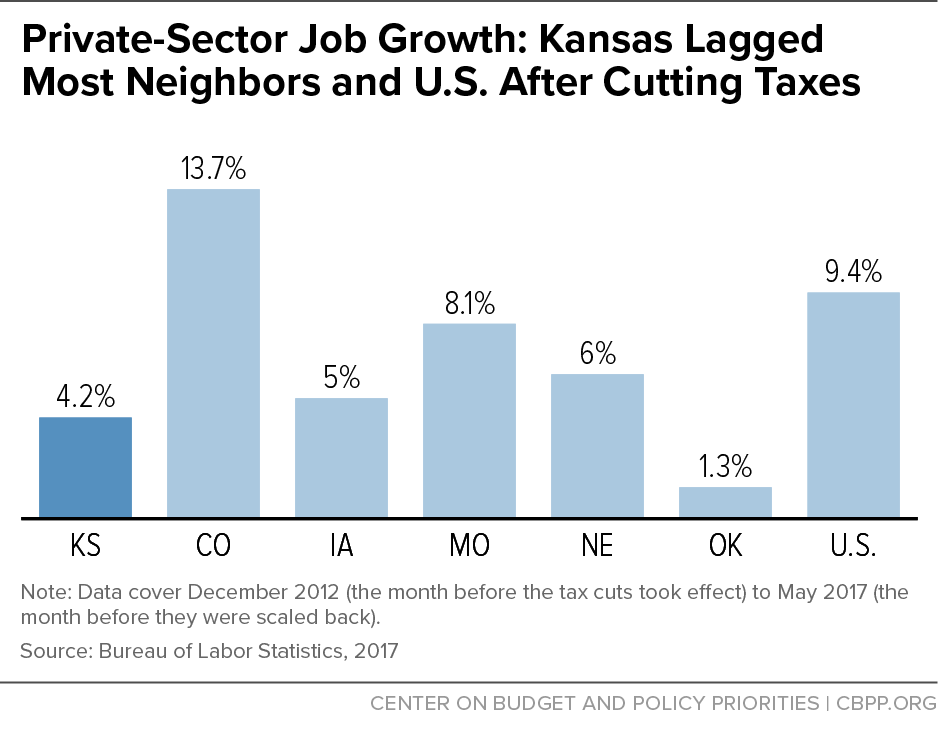

[16] The same is true if the comparison begins in April 2012, the month before the tax cut was enacted. It is worth noting that the only neighboring state that underperformed Kansas in job creation, Oklahoma, also cut its income tax rates during this period. None of Kansas’ other neighbors cut their income taxes significantly.

The Kansas Policy Institute (KPI), a conservative think tank that supported the Brownback tax cuts and opposed repealing them, argues for the use of a different job creation measure (which, unlike the Bureau of Labor Statistic data used in Figure 1, counts pass-through owners themselves as employees) and a different set of comparison states (based on a statistical analysis of which states’ employment bases are most similar to Kansas’). See Dr. William Boyes and Stephen Slivinski, “A Thousand Flowers Blooming: Understanding Job Growth and the Kansas Tax Reforms,” January 2017, https://kansaspolicy.org/job-growth-and-kansas-tax-reforms/. Without debating the merits of those arguments, making those substitutions does not result in an appreciably different picture. From 2012 to 2016, Kansas’ private-sector job growth rate using the alternative job creation measure was roughly three-fifths the rate of all 50 states taken together and below or equal to that of five of the eight recommended comparison states (Alabama, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, and Ohio) and only slightly better than a sixth, Nebraska.

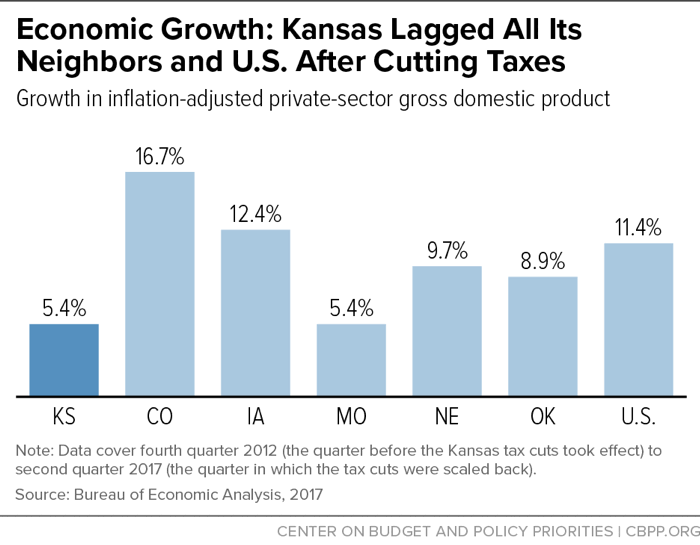

[17] Kansas’ economic growth was slightly slower than Missouri’s when measured to two decimal places. Kansas’ economic growth during this period was also slower than all of the five additional states that KPI argues should be compared to Kansas: Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Michigan, and Ohio.

[18] American Community Survey data extracted using American FactFinder.

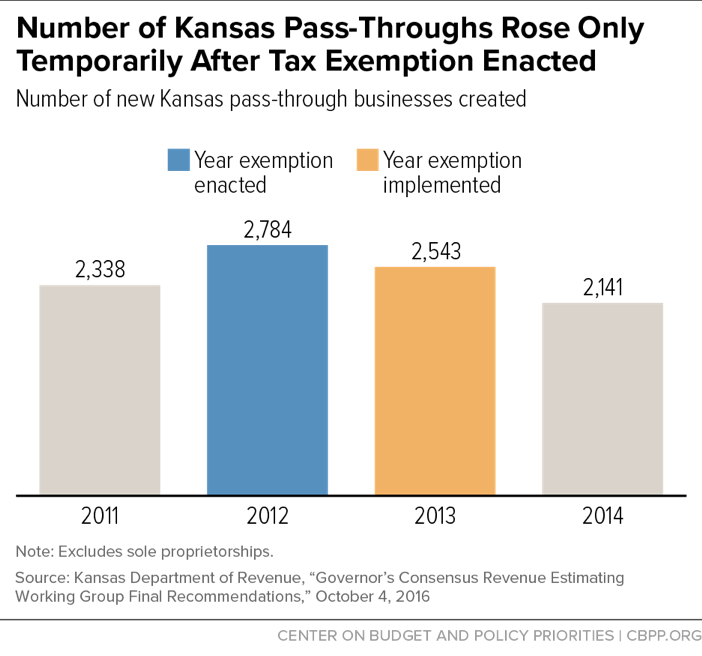

[19] “Governor’s Consensus Revenue Estimating Working Group Final Recommendations,” October 4, 2016, p. 9; http://budget.ks.gov/files/FY2017/cre_workgroup_report.pdf. Comparable data are not available from other states.

[20] Richard Prisinzano et al., “Methodology to Identify Small Businesses,” U.S. Dept. of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, Technical Paper 4 (Update), November 2016, p. 27.

[21] U.S. Census Bureau, County Business Patterns, 2015 data via American FactFinder.

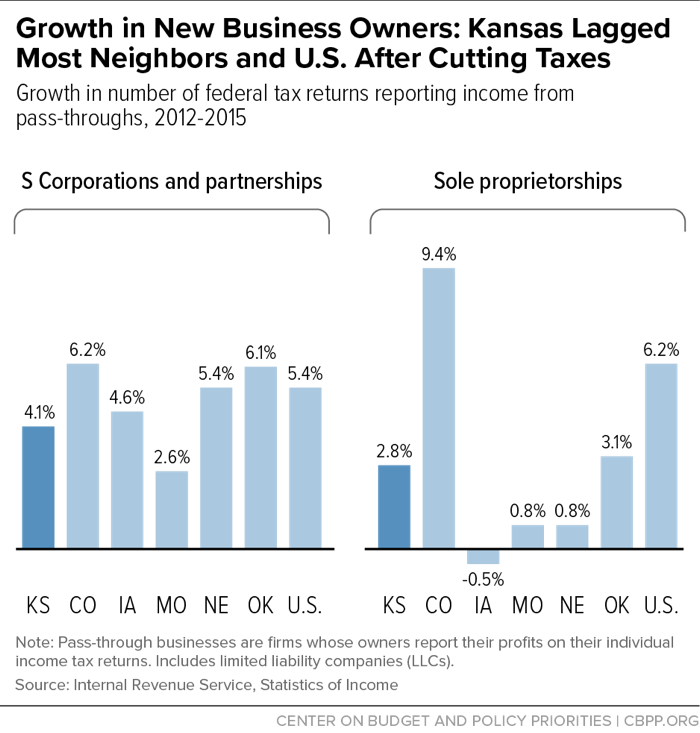

[22] “The reform had no measurable impact on the number of filers reporting income from S-corporations or partnerships.” Jason DeBacker et al., “The Impact of State Taxes on Pass-Through Businesses: Evidence from the 2012 Kansas Income Tax Reform,” September 2017, p. 20, https://papers.ssrn.com/soL3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2958353.

[23] Tracy M. Turner and Brandon Blagg, “The Short-term Effects of the Kansas Income Tax Cuts on Employment Growth,” Public Finance Review, 2017, p. 16, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1091142117699274.

[24] The “synthetic control methodology” used in the paper creates a comparison group of states by applying different weights to the various states’ recent economic performance as well as measures that should, theoretically, contribute to that performance (such as education levels). It should be acknowledged that the authors are critical of the types of neighboring states comparisons used in the other two studies summarized here.

[25] Dan S. Rickman and Hongbo Wang, “Two Tales of Two U.S. States: Regional Fiscal Austerity and Economic Performance,” March 19, 2017, pp. 15-16, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/79615/1/MPRA_paper_79615.pdf. (References in the quote were omitted.)

[26] Arthur Laffer and Stephen Moore, “Taxes Really Do Matter: Look at the States,” Laffer Center for Supply-Side Economics, September 2012, p. 17, http://www.laffercenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2012-09-TaxesDoMatterLookAtStates-LafferCenter-Laffer-Moore.pdf.

[27] Jonathan Curry, “Undeterred by ‘Kansas Experiment,’ Laffer Presses Tax Cuts,” State Tax Today, August 9, 2017.

[28] Arthur B. Laffer, Stephen Moore, and Jonathan Williams, Rich States, Poor States, 6th Edition, American Legislative Exchange Council, 2013, p. 3.

[29] Jonathan Williams and Ben Wilterdink, “Lessons from Kansas: A Behind the Scenes Look at America’s Most Discussed Tax Reform Effort,” American Legislative Exchange Council, February 2017.

[30] Interview with Nick Gillespie, Reason TV, April 22, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3tFqzeXI0g&.

[31] Russell Berman, “The Death of Kansas’ Conservative Experiment,” The Atlantic, June 7, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/06/kansass-conservative-tax-experiment-is-dead/529551/.

[32] Cato Institute, “Fiscal Policy Report Card on America’s Governors, 2012,” https://object.cato.org/pubs/wtpapers/GRC2012.pdf.

[33] Report Card, p. 24.

[34] Ryan Bourne, “The Real Lessons from the Kansas Experiment,” Cato, June 28, 2017, https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/real-lessons-kansas-experiment.

[35] Quoted in Berman, Note 31.

[36] Jeff Glendening, “Historic Tax Hike Won’t Fix Spending Problem,” Wichita Eagle, July 2, 2017, http://www.kansas.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/article159217439.html. In contrast, the Tax Foundation has acknowledged that Kansas’ “[s]pending growth has been slow, averaging about 0.5 percent in recent years . . . and just 0.3 percent per year since 2008.” Scott Drenkard and Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Testimony: Reexamining Kansas’ Pass-through Carve-Out,” January 19, 2017 (updated May 18, 2017 and June 30, 2017), https://taxfoundation.org/testimony-reexamining-kansas-pass-through-carve-out/.

[37] Kansas Legislative Research Department, “Kansas Fiscal Facts,” July 2017, p. 34, http://www.kslegresearch.org/KLRD-web/Publications/FiscalFacts/2017_fiscal_facts.pdf. (Change in full-time equivalent employment).

[38] Jonathan Shorman, “Brownback Asks Agencies to Show How They Will Deal with Five Percent Cuts,” Hutchinson News, August 11, 2016, http://www.hutchnews.com/7482195d-6874-5ead-914f-a6b64bfdeb5d.html. For examples of these mid-year budget cuts, see Bryan Lowry and Dion Lefler, “Brownback Moves Money from Highway Fund, Cuts Pension Spending to Deal with $279M Shortfall,” Wichita Eagle, December 9, 2014, http://www.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article4382802.html; Brad Cooper, “Gov. Sam Brownback Is Cutting Aid to Kansas Schools by $44.5 Million,” Kansas City Star, February 5, 2015, http://www.kansascity.com/news/politics-government/article9376751.html.

[39] CBPP calculations for Michael Mitchell, Michael Leachman, and Kathleen Masterson, “A Lost Decade in Higher Education Funding: State Cuts Have Driven Up Tuition and Reduced Quality,” August 22, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2017_higher_ed_8-22-17_final.pdf.

[40] A table the Department of Transportation prepared in January 2017 showed actual “extraordinary” transfers from the state highway fund to the General Fund or directly to state agencies between fiscal years 2013 and 2016 totaling $908 million (http://kslegislature.org/li/b2017_18/committees/ctte_h_apprprtns_1/documents/testimony/20170308_06.pdf). Transfers in 2017 have not been publicly reported, although at the time the table was prepared Governor Brownback was recommending an additional $398 million. See also Micheal Mahoney, “Kansas Budget Cuts to Put 25 Highway Projects on Hold,” KMBC TV, May 19, 2016, http://www.kmbc.com/news/kansas-budget-cuts-to-put-25-highway-projects-on-hold/39631246.

[41] State of Kansas, “Comparison Report,” August 2017, p. 18, http://budget.ks.gov/publications/FY2018/FY2018_Comparison_Report--8-4-2017.pdf. “Editorial: No More KPERS Delays,” Topeka Capital-Journal, September 17, 2016, http://cjonline.com/opinion/2016-09-17/editorial-no-more-kpers-delays.

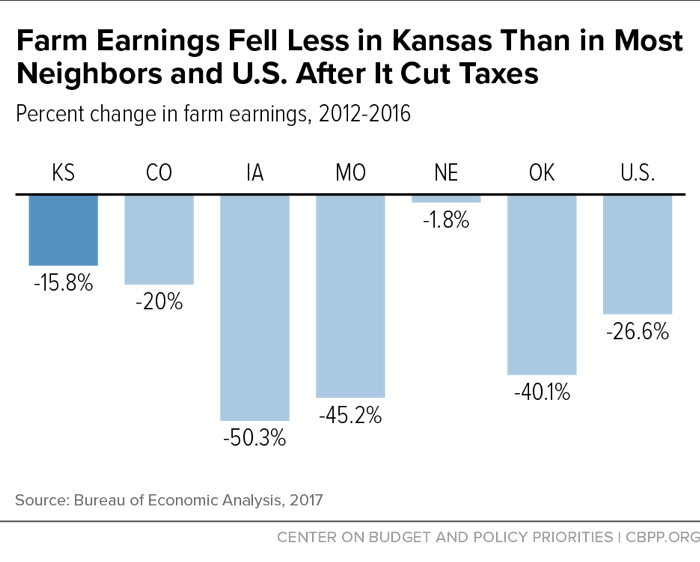

[42] Stephen Moore, “What’s the Matter with Kansas Republicans?” The Weekly Standard, May 22, 2017, http://www.weeklystandard.com/whats-the-matter-with-kansas-republicans/article/2008157. The Cato Institute has made a similar claim: “[T]he state is strongly affected by what goes on in the agricultural and energy industries. Given the weakness of commodity prices over this period, the state economy has struggled for reasons nothing to do with the tax cuts.” See Bourne, Note 34.

[43] Williams and Wilterdink, Note 29, p. 14.

[44] Bureau of Labor Statistics State and Local Area Employment database, https://www.bls.gov/sae/data.htm. State employment data at this level of industry disaggregation are not available on a seasonally adjusted basis.

[45] Economist Peter Fisher suggested separating Wichita-area employment from the rest of the state as an approach to isolating the effects of the downturn in aircraft manufacturing. See: Peter Fisher, “The Lessons of Kansas,” 2017, http://www.gradingstates.org/the-problem-with-tax-cutting-as-economic-policy/the-lessons-of-kansas/?print=pdf.

[46] University of Wisconsin economist Menzie Chin examined the impact of the aerospace industry on the output (“gross domestic product”) of the Kansas economy from 2010 through the first quarter of 2016. He found that the industry made a net positive contribution to Kansas output growth in most of the calendar quarters subsequent to the beginning of 2013, when the tax cuts took effect. See “Does the Aerospace Decline Explain the Kansas Collapse?” Econbrowser blog, August 12, 2016, http://econbrowser.com/archives/2016/08/does-the-aerospace-decline-explain-the-kansas-collapse.

[47] The fall from peak employment in the mining and logging sector, which occurred almost a year after the tax cuts took effect (December 2013), has been 4,100 persons.

[48] Other reasons include the regressive distributional impact that tax cuts justified on economic development grounds often have, and the fact that tax cuts likely impair a state’s ability to provide services that are critical to its long-run economic success, such as an educated and healthy work force and high-quality roads, bridges, and other infrastructure.

[49] For a discussion of the importance of entrepreneurship to state economic growth, see Michael Mazerov and Michael Leachman, “State Job Creation Strategies Often Off Base,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 3, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2-3-16sfp.pdf.

[50] The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Kansas’ aerospace manufacturing industry is poised for an upturn and that industry leaders are now quite concerned now about its ability to attract enough skilled workers in light of the large number who have left the state or will soon retire. See Shayndi Raice, “The ‘Air Capital of the World’ Has a Problem: Too Few Aviation Workers,” Wall Street Journal, August 2, 2017. Unfortunately, the cuts in higher education and national press coverage of the fiscal, economic, and political problems that the tax cuts have engendered have harmed the state’s ability to generate such workers internally and attract them from other states.

[51] Nicholas Johnson and Michael Mazerov, “Proposed Kansas Tax Break for ‘Pass-Through’ Profits Is Poorly Targeted and Will Not Create Jobs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised March 26, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/1-24-12sfp.pdf, pp. 5-6. The Tax Foundation raised similar concerns after the package was enacted: Mark Robyn, “Not in Kansas Anymore: Income Taxes on Pass-Through Businesses Eliminated,” Tax Foundation, May 29, 2012, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/ff302.pdf.

[52] The Kansas Policy Institute has explained why relatively few modestly compensated employees could be expected to take such a step: “For individuals, the choice comes down to whether they want to maintain traditional employment — with the advantages that come with being a full-time employee, such as the employer 401(k) matching contributions and group health insurance benefits — or transition to self-employment, even if it is an arrangement in which that employee simply becomes a ‘freelance’ contractor (i.e., Schedule C) while continuing to do the same full-time job. The loss of these benefits and various legal protections that come with being a traditional employee suggests that maintaining their status as a traditional employee is likely a better option than going through the accounting gymnastics involved in becoming a Schedule C worker just to avoid state income tax.” Page 5 of the source cited in Note 16.

[53] Associated Press, “KU Coach Bill Self, Other LLCs Avoid Taxes Under Kansas Law,” Topeka Capital-Journal, May 17, 2016 (updated November 2, 2016), http://cjonline.com/news-sports-catzone-hawkzone/2016-05-17/ku-coach-bill-self-other-llcs-avoid-taxes-under-kansas-law.

[54] Bryan Lowery, “More Business Owners Using Tax Exemption in Kansas than Expected,” Wichita Eagle, February 21, 2015, http://www.kansas.com/news/politics-government/article10802204.html.

[55] Of course, the Brownback administration itself cited the increase as providing evidence that the exemption had, in fact, stimulated the creation of new businesses. In the same Wichita Eagle article, Kansas Secretary of Revenue Nick Jordan said, “in tax year 2013 alone there were 8,666 new filers . . . the [191,000] estimate was based on data from 2009, [and] much of the difference is because of four years of growth in small businesses.” And, as recently as late July 2017, Arthur Laffer made the same claim: “[T]here was a huge increase in overall number of businesses as well, which is exactly why they did it.” “If that isn’t a supply-side response, I don’t know what is.” Quoted in Jonathan Curry, “Undeterred by ‘Kansas Experiment,’ Laffer Presses Tax Cuts,” State Tax Today, August 9, 2017.

[56] Dave Trabert, “IRS Data Refutes Kansas Tax Evasion Theories,” Kansas Policy Institute, May 17, 2017, https://kansaspolicy.org/irs-data-refutes-kansas-tax-evasion-theories/.

[57] The 2009 data for Kansas are available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/09in17ks.xls.

[58] Non-resident owners of pass-through businesses operating in Kansas might also benefit from the exemption, but they would not be picked up in the IRS data. The apparent discrepancy between the 2.0 percent growth in Kansas returns reporting passthrough income cited here and the growth rates shown in Figure 4 is explained by the fact that the former includes farm income returns and the latter does not. The number of Kansas farms declined between 2012 and 2015.

[59] See the source cited in Note 34.

[60] See the source cited in Note 23, pp. 16-17.

[61] The fact that Kansas outperformed three of its five neighbors in the growth of sole proprietorships between 2012 and 2015 (see Figure 4) may also reflect adoption of the second tax avoidance strategy described above — that is, people deciding to become independent contractors to their former employers.

[62] See Note 22.

[63] See the source cited in Note 19, p. 9.

[64] See the source cited in Note 19, pp. 10-11.

[65] See Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: Still a Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-21-13sfp.pdf.

[66] Leachman and Mazerov, preceding Note.