- Home

- Joint Tax Committee Estimate Shows That ...

Joint Tax Committee Estimate Shows That Tax Gimmick Being Designed To Evade Senate Budget Rules Would Increase Long-Term Deficits

Summary

House and Senate conferees negotiating an agreement on the tax reconciliation bill are widely reported to have decided to use a change in Roth IRAs to help “offset” the cost of capital gains and dividend tax cuts in years after 2010. If the tax reconciliation bill increases the deficit after 2010, it would violate a Senate rule that a reconciliation bill may not increase long-term deficits, and the bill would be subject to a 60-vote point of order on the Senate floor. The Roth IRA provision, in conjunction with other provisions, is supposed to address this problem.

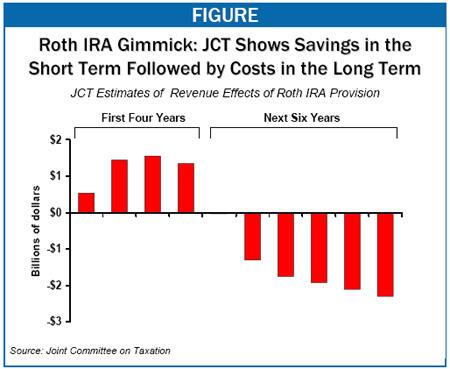

New estimates by the Joint Committee on Taxation show, however, that the Roth IRA proposal is a gimmick — while it would raise revenues in the first few years it was in effect, it would produce sizeable revenue losses in the years after that (see the Figure below and the Joint Tax Committee document below). The new Joint Tax Committee estimates confirm that the proposal represents a flagrant deception, under which conferees would seek to create an illusion they were notincreasing long-term deficits when in fact that would be precisely what they were doing.

Approach Would Add New Tax Cuts to "Pay For" Other Tax Cuts

The White House and Congressional leaders have insisted that the tax reconciliation bill must include a two-year extension of the capital gains and dividend tax cuts, which are slated to expire after 2008. This extension costs $51 billion according to the Joint Committee on Taxation, with $30 billion of that cost coming in 2011-2015, after the end of the five-year budget reconciliation period (which runs from 2006-2010). Under Senate rules, reconciliation bills that increase deficits in years after the reconciliation period (in this case, after 2010) are barred and trigger a Senate point of order that requires 60 votes to override. To include the capital gains and dividend tax cuts in reconciliation without triggering a Senate point of order, the conferees are widely reported to have agreed to use a two-step device.

-

First, they would use two tax cuts — one involving Roth IRAs and the other involving a tax break for small businesses — as a way to help “pay for” the costs of the capital gains and dividend tax cut in the years from 2011 to 2015. The two tax cuts in question both would change the timing of tax payments. While both of these tax breaks would lose revenue overall, they can be structured so that they raise revenue from 2011-2015, which are the only years after the end of the reconciliation period (2006-2010) for which the Joint Tax Committee will produce official cost estimates. (The Joint Committee does not produce revenue estimates for periods of more than ten years.)

-

The second step is that the conferees will seek to have the Senate Parliamentarian limit his assessment of whether the bill increases deficits after the end of the reconciliation period to the years from 2011-2015. This restricted view is necessary for the gimmick to work. Senate rules bar reconciliation bills from increasing deficits in any years outside the reconciliation budget period, not just in the first five years after the end of the period, and new estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation confirm that after raising revenue for a few years, the Roth IRA provision loses substantial amounts of revenue in subsequent years. There is simply no question but that the IRA provision will increase long-term deficits, with the result that the conference report will violate the Senate’s rule against reconciliation bills that increase long-term deficits. The negotiators will seek to hide this fact, however, by delaying the implementation of the Roth proposal so that all of the revenue gains will occur in the years through 2015, and the revenue losses will occur after that, with the result that the official ten-year cost estimate of the reconciliation bill will reflect none of the revenue losses.

To Work, Gimmick Requires Support of Senate Budget Committee Chair

Whether this audacious plan will succeed will largely depend on Senate Budget Committee Chairman Judd Gregg. Were the Senate Parliamentarian to acknowledge what analysts know to be true — that the Roth IRA proposal causes long-term revenue losses — the bill would have to be found to violate Senate rules and to need 60 votes to pass. The Parliamentarian traditionally defers, however, to the Senate Budget Committee Chairman for guidance on interpreting budget estimates, and Chairman Gregg’s comments indicate that he is favorably disposed toward this gimmick. He told reporters that if the official estimates show the Roth IRA proposal as “neutralizing” the cost of the capital gains and dividend extension after 2010, he would “have no problem adopting it.”[1] Senator Gregg’s statement stands in contrast to his expressions of alarm regarding long-term deficits and his calls for budget reforms to keep Congress from evading fiscal discipline in other parts of the budget (i.e. areas other than tax cuts), reflected most recently in an op-ed he wrote that appeared in the Wall Street Journal.[2]

A Senate rule imposed in the Congressional budget resolution for fiscal year 2006 — adopted in Senator Gregg’s first year as Chairman of the Budget Committee — restricts increases in entitlement spending in years beyond those covered by the budget resolution.[3] That rule calls for the Congressional Budget Office to prepare an estimate for each bill or conference report showing whether that legislation would increase entitlement spending by $5 billion in any of the four 10-year periods following 2015. Clearly, Chairman Gregg believed it was important to rely on estimates of the long-term effects of spending provisions in order to fairly enforce that Senate rule.

If Chairman Gregg takes the position that in this case he should rely only on the Joint Tax Committee’s 10-year estimate of the tax reconciliation bill and fails to acknowledge that the Roth IRA proposal would increase deficits after 2015 — despite the findings of the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Congressional Research Service, and various budget watchdog groups, which show there is no question this is the case[4] — and the Parliamentarian accepts his judgment, then conferees will have succeeded in pulling off a flagrant budget gimmick that causes the nation’s already grim fiscal outlook to grow still worse.

How the Roth IRA Gimmick Works

The proposal reportedly under consideration would remove the income limits from Roth IRAs, possibly for a temporary period. Under current law, individuals with income above $110,000 and couples with income above $160,000 cannot contribute to a Roth IRA. Further, individuals and couples cannot rollover — or convert — retirement savings they hold in a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA if their income is above $100,000. Lifting the income limits on Roth IRAs will spur a large number of high-income households to convert their traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs in order to take advantage of the Roth IRA tax breaks.

When a traditional IRA is converted to a Roth IRA, income taxes are paid on the funds that are converted. This tax payment is required because of the different structures of the two types of IRAs. Traditional IRAs are “front loaded,” with the main tax benefit occurring up-front. The income deposited in the IRA is deductible, and hence is exempt from tax.[5] These funds grow tax free in the account but are taxed when they are withdrawn in retirement. The Roth IRA tax breaks, by contrast, are “back-loaded.” No deduction is available for funds deposited in these accounts, so the deposits are made with after-tax income. The funds then accumulate free of tax in the account, and unlike with traditional IRAs, the funds are tax free when withdrawn in retirement. Accordingly, in converting a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, a person agrees to pay income taxes now on the amount in his or her traditional IRA, which has not yet been subject to tax, in exchange for being relieved from paying tax later on these funds (and the earnings on them) when he or she withdraws the funds in retirement. The conversion process is essentially a timing shift, with taxes being paid now instead of later.

To make conversions from traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs more attractive, the conferees on the tax reconciliation bill are expected to permit taxpayers who convert these funds to spread the amounts being converted over several years for tax purposes. This enables these individuals to spread the tax payments on the converted funds over several years. For some people, this also prevents the converted amounts from pushing them into higher tax brackets.

This provision is apparently being designed in the tax reconciliation conference report in such a way as to ensure that the taxes on the conversions would be paid primarily or entirely in the 2011-2015 period. The revenues collected in those years as a result of this timing shift would then be used to “offset” the costs in those years of the extension of the capital gains and dividend tax cuts.

Joint Tax Committee Estimate Shows Proposal Ultimately Loses Revenue

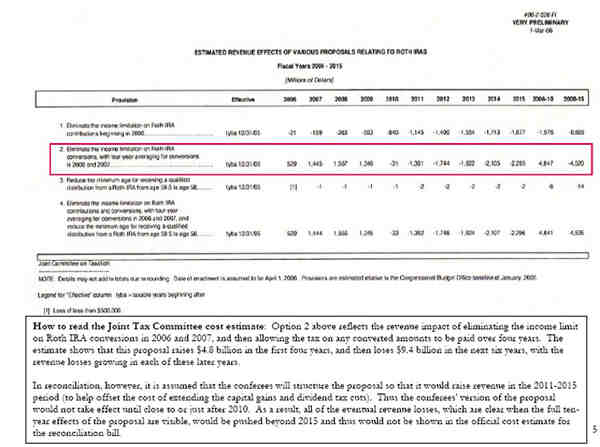

The Joint Committee on Taxation recently examined the proposal to lift the income limit on Roth IRA conversions, assuming that the change would be effective in 2006 and 2007, with the income tax payments spread over the following four years. The Joint Committee found this proposal would raise nearly $5 billion in the first four years it was in effect, as high-income taxpayers converted their traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs and made the associated tax payments. But the Joint Committee found that the proposal would then lose more than $9 billion over the subsequent six years, with the losses exceeding $2 billion a year by the end of the ten-year period.[6] (See option 2 of the attached Joint Tax Committee cost estimate.)

The conferees on the tax reconciliation bill are virtually certain to “time” the IRA provision so it does not take effect until close to or just after the end of the 2006-2010 period, with the tax payments on the amounts that are converted from traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs being spread over most or all of the 2011-2015 period. In other words, the increased revenues that the attached Joint Tax Committee estimate shows being collected in 2006-2009 would be collected in the 2011-2015 period instead. And the revenue losses that the Joint Committee estimate shows in the 2010- 2015 period would be pushed beyond 2015 — and thereby hidden; since Joint Tax Committee estimates do not extend beyond ten years, these costs would not be visible. Thus, there would be no official estimate showing the revenue losses that the Roth IRA provision ultimately would produce.

The Congressional Research Service, in an analysis prepared in late February, similarly found that there is no question but that the Roth IRA proposal ultimately loses revenue. CRS reported that “the [Roth IRA] rollover provision, from a budgetary standpoint, simply speeds up tax payments, causing revenue gains today and a loss, with interest, in the future” [7] (emphasis added). This is the case, CRS explained, regardless of whether the rollover provision is permanent or is slated to expire after a few years.

It also is important to recognize that the provision is more than simply a timing shift that can be used to accelerate into the 2011-2015 period revenues that would otherwise be collected in subsequent years. Over the long run, the proposal would result in a net reduction in tax revenues. This would occur because people would only elect to convert their traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs if doing so would be to their advantage because it would lower their tax bills; that is, they would elect to pay some taxes now if they expected that would reduce their tax bills by a larger amount in the future. The revenue losses would be even greater if, as expected, the $160,000 income limit on who can make contributions to Roth IRAs is lifted as well; such a change would represent a clear expansion of Roth IRAs and lose still more revenue over time.

Click to view a larger version of the table

Other Gimmicks Expected in Tax Reconciliation Bill

Another gimmick expected to be part of the final reconciliation package involves a tax break for small businesses. Both the House and Senate versions of the tax reconciliation bill include a two-year extension of a provision enacted in 2003 and now slated to expire at the end of 2007,which permits small businesses to write-off (or “expense”) up to $100,000 each year in equipment purchase costs. (This amount has been indexed to inflation since 2003, so it is set at $108,000in 2006.) In the absence of this provision, businesses would deduct the cost of equipment purchases over a number of years spanning the life of the equipment.

This provision, too, essentially represents a timing shift, since businesses would be permitted to deduct more upfront, and to deduct less later on, than under normal tax rules. As a result, the proposal contained in the House and Senate tax reconciliation bills would cost $7.3 billion in the first five years and save $7.0 billion over the subsequent five years.

In the conference agreement, this $7 billion in savings in the 2011-2015 period is expected to be used, along with the Roth IRA proposal, to help offset the cost in these years of extending the capital gains and dividend tax cuts. Moreover, the “savings” from this provision will be significantly greater than $7 billion in the 2011-2015 period, because the conferees reportedly are sweetening this provision by quadrupling the expensing limit to $400,000 a year, even though such an expansion was not included in either the House or Senate bills. This will increase the cost of the provision through 2010 — and increase the apparent savings after 2010.

The savings in 2011-2015 for which the conferees would get credit, however, would likely prove illusory. These savings would depend upon the provision actually expiring on schedule. Like many other “temporary” business tax cuts that routinely are extended when they are slated to expire, however, this provision likely would never die. And if the provision ultimately were extended, as it likely would be, the savings ostensibly being used to help offset the cost of the capital gains and dividend tax cuts in the 2011-2015 period would likely never materialize.

“Paying for” Some Tax Cuts with Other Tax Cuts

This provision, like the Roth IRA proposal, is a tax cut. In essence, conferees are planning to portray the tax reconciliation bill as being deficit-neutral after 2010 by using timing gimmicks that make it appear as though one set of tax cuts is “paying for” another set of tax cuts. The net effect of all of these cuts, of course, is to lose revenue.

Conferees also may be considering other gimmicks to appear to mitigate the deficit impact of the bill after 2010. For example, conferees may be considering gimmicks used to hit revenue targets for previous tax cut bills, such as manipulating the dates of various corporate tax payments. The unfortunate bottom line is that the forthcoming tax reconciliation conference agreement is likely to continue the tradition of the 2001 and 2003 tax-cut bills — of using timing gimmicks and other devices to make tax cuts appear to be less costly, and less damaging to the nation’s fiscal health, than is actually the case.

End Notes

[1] Kurt Ritterpusch and Jonathan Nicholson, “IRA Conversion Proposal Draws Attention As Means to Stave Off Tax Bill Point of Order,” Bureau of National Affairs Daily Tax Report, March 29, 2006.

[2] Judd Gregg, “The Safety Valve Has Become a Fire Hose,” Wall Street Journal, April 18, 2006.

[3] See James Horney, “New Enforcement Mechanism in Senate Budget Plan Would Favor Tax Breaks and Distort Policy Debates,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 22, 2005.

[4] See Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Committee for Economic Development, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, and the Concord Coalition “Joint Statement Opposing Potential Budget Gimmick,” March 28, 2006.

[5] Note that the deduction is not available to taxpayers above certain income levels who have pension coverage through their employers. These taxpayers can still contribute to traditional IRAs, but with after-tax funds, so the tax benefit they receive is only from the tax-free growth of these funds before they are withdrawn in retirement.

[6] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects of Various Proposals Relating to Roth IRAs,” March 1, 2006.

[7] Jane G. Gravelle, “Budgetary Effects of Alternative Individual Retirement Account (IRA) Policies,” Congressional Research Service memorandum, February 27, 2006.

More from the Authors