The bipartisan budget agreement reached in July eliminated the threat of deep, damaging cuts under the 2011 Budget Control Act and opened the way for Congress to finalize fiscal year 2020 appropriations bills that invest in key domestic priorities.[1] One such priority should be the Housing Choice Voucher program, which helps 5 million people — most of whom are children, seniors, or people with disabilities — in more than 2 million households pay the rent and make ends meet.[2] A near-record 8.3 million renter households with very low incomes either pay more than half their income for rent or live in severely substandard housing, and only 1 in 4 eligible households receive rental assistance due to funding limitations. Yet the number of households using housing vouchers has declined over the past two years due to funding delays and shortfalls caused by policymakers’ battles over federal spending. The budget agreement creates an opportunity to reverse these harmful losses and help more renters afford decent, stable homes.

Congress should follow the path of the House-approved 2020 funding bill for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which provides $23.8 billion for vouchers, $1.2 billion (5.4 percent) over the 2019 level. Most of this increase is necessary to renew all of the 2.2 million vouchers that households are now using and prevent cuts in the number of assisted households. (Voucher funding must rise every year to account for rising rents and other factors.) The House bill also includes $80 million to provide approximately 8,500 new vouchers for homeless veterans and at-risk families and youth. In addition, it provides $25 million to expand a promising mobility initiative designed to help families that would like to move from their current neighborhoods due to concerns such as high crime or poorly performing schools and find housing in neighborhoods with higher-quality schools and other opportunities that improve their children’s long-term chances of success.

Other areas in the HUD funding bill also merit additional resources. For instance, the House bill boosts funding for public housing, homeless assistance grants, and the Family Self-Sufficiency program. Added investments in these areas would preserve badly needed public housing, help more individuals and families move from homelessness into stable homes, and support families’ efforts to work and increase their incomes.

Housing vouchers are highly effective at reducing housing instability and other hardships among low-income households struggling with high housing costs. They help seniors and people with disabilities live with dignity in the communities they choose and help families with children live near quality schools and other opportunities. A solid body of research finds that vouchers:

- Lift more than one-third of the households that use them out of poverty, freeing up resources that they may spend on food, medical care, and child care, as well as other goods and services that can enrich their children’s lives;[3]

- Sharply reduce homeless, overcrowding, food insecurity, and other hardships;[4] and

- Improve children’s chances of growing up to be productive adults. Children score higher on cognitive tests, for example, when their families live in housing they can afford.[5] In addition, when families that choose to are able to use housing vouchers to live in neighborhoods with more opportunities, their children are more likely to attend college and less likely to become single parents, and they earn more as young adults.[6]

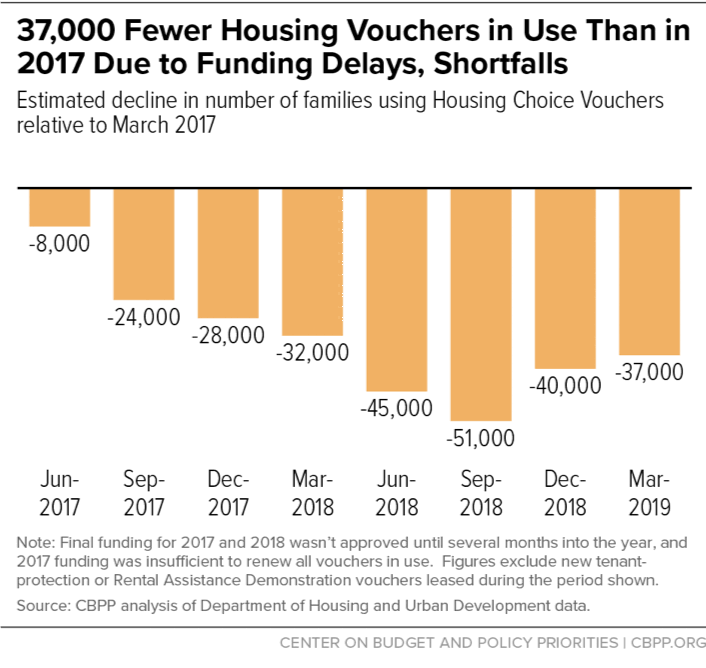

Despite its proven benefits, the voucher program now assists about 37,000 fewer households than in early 2017. This partly reflects policymakers’ failure to anticipate a jump in program costs in fiscal year 2017; agencies across the country received $565 million less that year than they needed to renew all vouchers that households were using.

Funding delays caused by recent battles over discretionary funding have also played a role. Policymakers delayed final funding decisions well beyond the October 1 start of the fiscal year in 2017, 2018, and 2019, when the final bills were not enacted until the following May, March, and February, respectively. When long delays such as these occur, housing agencies must often make difficult decisions about how many vouchers to renew amid rising rental costs and deep uncertainty about their final program budgets. Many react cautiously by reissuing fewer vouchers when families leave the program, thereby reducing the number of households assisted while they await policymakers’ final decisions. This reaction, while understandable, worsens the problem: serving fewer families in one year reduces those agencies’ funding eligibility in the next year because eligibility for most agencies is based on voucher usage and costs in the prior year.

The inadequate funding provided in 2017, coupled with the funding delays and housing agencies’ reaction to those delays, have created a downward spiral in the voucher program, as the number of households using vouchers fell sharply in 2017 and most of 2018. (See Figure 1.) Funding increases for 2018 and 2019 enabled agencies to reverse some of these losses, but as of March 2019, about 37,000 fewer families were using vouchers than two years earlier.

To fully reverse these losses over the coming year, policymakers must avoid delays in finalizing fiscal year 2020 appropriations and provide sufficient funding to fully renew all vouchers now in use, as well as to expand the program modestly to reach more families. Specifically, they should follow the House’s lead by providing at least $23.8 billion for vouchers. The House bill includes the following:[7]

-

$21.4 billion to renew the 2.2 million vouchers that families, seniors, and others are now using. This is a $1.1 billion (5.4 percent) increase over the 2019 level. The increase is necessary in part because per-voucher costs are rising more than 3 percent annually, roughly consistent with trends in the private rental markets where vouchers are used.[8] In addition, slightly more vouchers will likely require renewal in 2020 than in 2019, largely because thousands of new vouchers recently funded for homeless veterans and others must be renewed for the first time in 2020.[9]

The House bill would also authorize HUD to provide modest additional funding (beyond the amount required to renew all vouchers in use) to high-performing agencies that have been forced by funding shortfalls to cut the number of households they assist, thereby enabling them to reissue vouchers to seniors, families, and other vulnerable households on their waiting lists.

- $40 million for 4,000 new Family Unification Program (FUP) vouchers for families and youth. These vouchers would help prevent children from being placed into foster care or enable them to return from foster care to their families, in cases where families’ lack of adequate housing is the primary reason for the placement. The House bill sets aside $20 million of this total for timely assistance to young adults who have recently exited foster care and are at risk of homelessness.

- $40 million for approximately 4,500 new supportive housing vouchers for homeless veterans. Investments in Veterans Affairs-Supportive Housing (VASH) vouchers have played a critical role in reducing homelessness among veterans by nearly 50 percent since 2010.[10]

- $25 million to double the size of the Housing Voucher Mobility Demonstration, which Congress initiated in the 2019 funding law. This innovative research initiative seeks to identify the most effective ways to help families with rental vouchers find safe, affordable housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods, if they wish to do so.[11]

At a time when millions of low-income seniors, families, and others struggle to pay rent, it is essential that policymakers invest in proven strategies such as housing vouchers, as well as the other areas in the HUD funding bill mentioned above.