Policymakers have periodically raised concerns about the rising cost of Housing Choice Vouchers, the nation’s largest rental aid program, and its impact on the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) budget. While Congress has made deep funding cuts in recent years in some HUD programs that provide critical support for low-income households — such as the public housing, HOME, and housing for seniors and people with disabilities programs — they were due to rigid funding caps, not housing voucher program costs.[1]

The binding funding caps instituted by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) — lowered further through cuts known as sequestration — constrained funding for non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs, including most of HUD’s budget. With fewer NDD resources to allocate, Congress cut annual HUD program funding by 9 percent, or $4.2 billion, from 2010 to 2017, in inflation-adjusted terms.

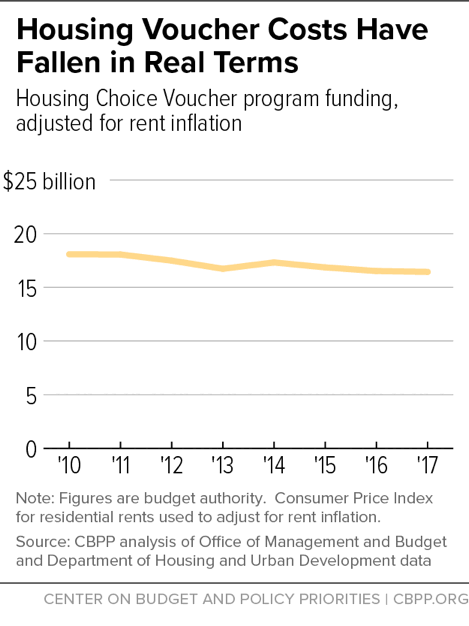

Within those overall reductions, Congress prioritized funding for the Housing Choice Voucher and other rental assistance programs, because of their importance in assisting struggling families, seniors, veterans, and people with disabilities to afford decent housing. The cost of the voucher program has grown, but by far less than one would expect for a program that helps low-income families afford housing in the private market. Private market rents rose 23 percent from 2010 to 2017, putting strong upward pressure on voucher subsidies, which must keep pace with market rents to make housing affordable for low-income families.[2] Yet total housing voucher program funding rose just 12 percent over the same period — or, put another way, voucher funding fell 9 percent after adjusting for rent inflation (see Figure 1).

Part of the rise in voucher program funding was due to policymakers, recognizing the program’s effectiveness, funding roughly 150,000 new vouchers for homeless veterans and other vulnerable households. These new vouchers are responsible for more than half of the program’s cost growth since 2010.

Vouchers’ funding increases have been critical to maintaining the program’s effectiveness and preventing cuts in the number of households receiving aid. At the same time, funding for other important HUD efforts has fallen short of need. Addressing these needs should not come at the cost of the voucher program, but by increasing overall funding for NDD programs, which include a broad set of core public services and investments, to better meet national needs.

The NDD cuts since 2010 would have been even larger if Congress had not enacted temporary measures to reduce (but not eliminate) the sequestration cuts that further lowered the caps. Those temporary measures have expired and Congress will consider in coming weeks whether to once again lessen the sequestration cuts for both defense and NDD programs. Such an agreement would help prevent further cuts in HUD housing and community development programs, as well as potentially free up additional rental assistance to help communities to make further progress in reducing homelessness and meeting other urgent housing needs.

Market Rents and Number of Families Using Vouchers Drive Program Costs

The Housing Choice Voucher program is the nation’s largest rental aid program, assisting 2.2 million working families, seniors, people with disabilities, and other low-income households, or 46 percent of all households that receive HUD-administered rental assistance.[3] Funded at $20.3 billion, housing vouchers made up 42 percent of the HUD program budget in 2017.[4]

Families use housing vouchers to rent available private market units in the communities of their choice. Typically, the household pays 30 percent of its income to cover the rent, and the voucher subsidy fills the gap between this payment and the rent, within reasonable limits that HUD and the local housing authority set.

A significant body of research finds that vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, overcrowding, and other hardships. They lift more than a million people out of poverty, and they give families an opportunity to move to safer neighborhoods with better access to quality schools and other household needs. These effects, in turn, are closely linked to educational, developmental, and health benefits that can improve children’s long-term prospects, enable frail seniors and people with disabilities to live in the community and avoid institutionalization, and reduce costs in other public programs.[5]

The program’s rent rules and reliance on the private housing stock are essential to its success. Vouchers reduce rents for low-income families to an affordable level — which is essential to reduce families’ risk of eviction and homelessness — and they do so at a lower cost to the government than other forms of housing assistance, research shows.[6] That’s partly because vouchers mainly help families rent existing housing, which generally costs less than building new housing developments. Vouchers also provide families with a wide range of housing options, enabling them to choose housing and communities that best meet their needs.

The voucher program is effective, however, only if private owners are willing to accept vouchers, and for that to happen, families, with the help of the voucher subsidy, must pay market rents. If voucher subsidies fail to keep pace with market rents, fewer landlords will accept vouchers, shrinking families’ housing options and making it difficult or even impossible for them to use vouchers. For the program to function effectively, voucher subsidies must keep pace with market rents over the long term. Program costs are thus driven in part by changes in those rents, as the renewal of voucher subsidies constitutes 90 percent of the voucher program budget.[7]

It is therefore reasonable to expect housing voucher program costs to rise and fall in accord with changes in market rents. In recent years, however, voucher program costs have risen much more slowly than market rents. From 2010 to 2017, market rents rose 23 percent, according to the consumer price index (CPI) for residential rents. Over the same period, housing voucher program funding rose from $18.1 billion to $20.2 billion, an increase of 12 percent.[8] Put another way, voucher funding fell 9 percent over this period, adjusted for rent inflation.[9] (See Figure 1.)

In addition, the program is assisting significantly more households in 2017 than it did in 2010, as policymakers funded some 150,000 new housing vouchers during this period. These include more than 50,000 new vouchers for homeless veterans under the HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH) program, and roughly 90,000 new “tenant protection” vouchers that HUD issues to replace public or other assisted housing that has been demolished or otherwise removed from service. These new vouchers are renewed annually, and such renewals have increased program costs by about 7 percent since 2010.[10]

The BCA’s tight spending caps have had a substantial cumulative impact over the past seven years. From 2010 to 2017, overall funding for NDD programs has fallen 13 percent after adjusting for inflation, a reduction that represents a loss of more than $70 billion in annual funding for child care aid, job training, wastewater treatment, elementary and secondary education, and many other areas of critical importance.[11]

The NDD cuts include sizeable cuts in HUD housing and community development programs. (See Figure 2.) To their credit, policymakers have provided additional funds in areas of the HUD budget — such as the housing voucher and Section 8 project-based rental assistance programs — where failing to do so would cause an immediate reduction in the number of low-income families, seniors, and others receiving the rent aid they need to afford a home. But other areas of the HUD budget have been hit hard.

For instance, annual funding for public housing, which provides affordable homes to more than 1 million low-income households, more than half of which are seniors or people with disabilities, has fallen $1.8 billion (22 percent) from 2010 to 2017. In 2010, public housing already had a $26 billion backlog of needed repairs, and the recent cuts have likely compelled agencies to defer additional work needed to maintain the quality of life for residents (such as replacing aging plumbing or heating systems) or protect them from serious safety hazards (such as fixing elevators, sprinklers, or security systems). When major renovations are deferred, developments could become uninhabitable, forcing agencies to demolish, board up, or sell the properties, eliminating needed affordable housing and squandering decades of federal and local investment.

In addition, the HOME block grant, which provides states and localities with flexible funds to support affordable housing development, has been cut $1.1 billion (53 percent); and the housing for seniors and people with disabilities programs have been cut $600 million (48 percent). Community Development Block Grant funding has also fallen $1.5 billion, or 33 percent.[12] If overall HUD funding had kept pace with general inflation from 2010 to 2017 — which would have made more than $4 billion available for HUD programs in 2017 — the vast majority of these cuts could have been avoided.

Additional resources are needed to sustain aid to the vulnerable households that are currently using housing vouchers, expand the availability of housing vouchers and other rental assistance to reduce homelessness, pay for the repairs needed to maintain public housing in safe and healthy condition, and reverse recent cuts in federal support for affordable housing development. To achieve these important goals, Congress must raise overall funding for NDD programs, as well as ensure that the additional resources are allocated to the most urgent priorities, including helping more low-income families to afford homes.