Options to Reduce State Medicaid Costs: Prescription Drugs

As states facing substantial budget shortfalls due to the COVID-19 economic crisis consider cost-saving options in Medicaid, they should explore ways to reduce prescription drug spending rather than cut benefits or provider reimbursement rates, which could reduce access to care.

How Do State Medicaid Programs Pay for Prescription Drugs?

State spending on outpatient prescription drugs includes two components — payments to pharmacies for the medication and the rebates the state receives from the pharmaceutical manufacturer. Payments to pharmacies are based on factors including the acquisition cost for the drug and the amount of the pharmacy dispensing fee.

Nearly all states contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) to provide some or all covered benefits to some or all enrollees, and most of these states include management of outpatient prescription drugs in their managed care contracts. Some managed care contracts allow the plan to negotiate prices with prescription drug manufacturers and make decisions about when and how enrollees access medications. Other states carve prescription drugs out of their managed care contracts, operating the prescription drug benefit separately.

Some states also have contracts with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which are independent companies that can negotiate rebates, manage preferred drug lists, and administer the prescription drug benefit. Some managed care plans with contracts that include the outpatient prescription drug benefit also contract with PBMs to manage this benefit.

What Is the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program?

States that include prescription drug coverage in their Medicaid programs — which all states do — must cover all drugs approved by the Federal Drug Administration (with limited exceptions, defined in the Medicaid statute).

In return for states covering all prescription drugs, prescription drug manufacturers must provide them with substantial rebates, giving them a much lower price than typically offered to commercial health plans. These rebates allow states and the federal government to achieve savings of about 50 percent.

States are also free to negotiate better deals with drug manufacturers, including additional rebates on top of those guaranteed under federal law. And while states cannot exclude coverage for FDA-approved drugs, they can limit enrollees’ access to specialized, high-cost drugs to ensure their efficient use. For example, states can require prior authorization for specialized medications or require Medicaid beneficiaries to try a lower-cost drug within a class before getting a higher-cost one.

What Can States Do to Reduce Prescription Drug Costs?

Federal law gives states a range of options to reduce prescription drug costs while maintaining enrollees’ access to needed medication. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s state Medicaid pharmacy survey for state fiscal years 2019 and 2020 provides detailed information on how states are reducing prescription drug costs.

-

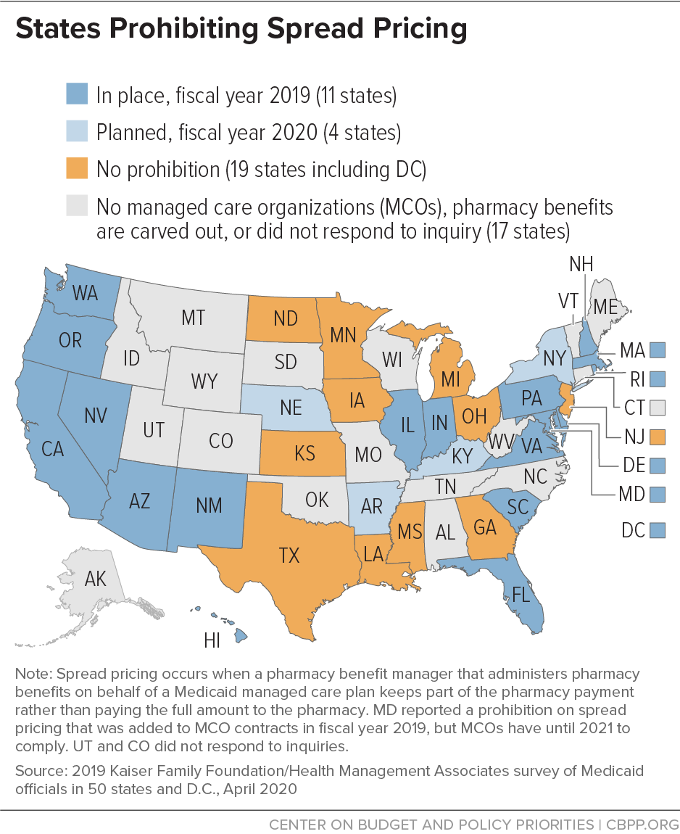

Prohibit spread pricing. Spread pricing occurs when a Medicaid managed care plan contracts with a PBM to administer pharmacy benefits and the PBM keeps a significant portion of the pharmacy payment rather than paying the full amount to the pharmacy. Compared with a fixed administrative fee, spread pricing allows PBMs’ payments and fees to be opaque, which makes it easier for the MCOs to build the increased price into their MCO rates, passing on the increased cost to state and federal governments in the future.

In May 2019, CMS released guidance encouraging states to prohibit spread pricing. As of July 1, 2019, only 11 states with MCO contracts reported that they had prohibited spread pricing, while an additional six states reported plans to do so, and 26 states reported plans to implement transparency or reporting requirements.

-

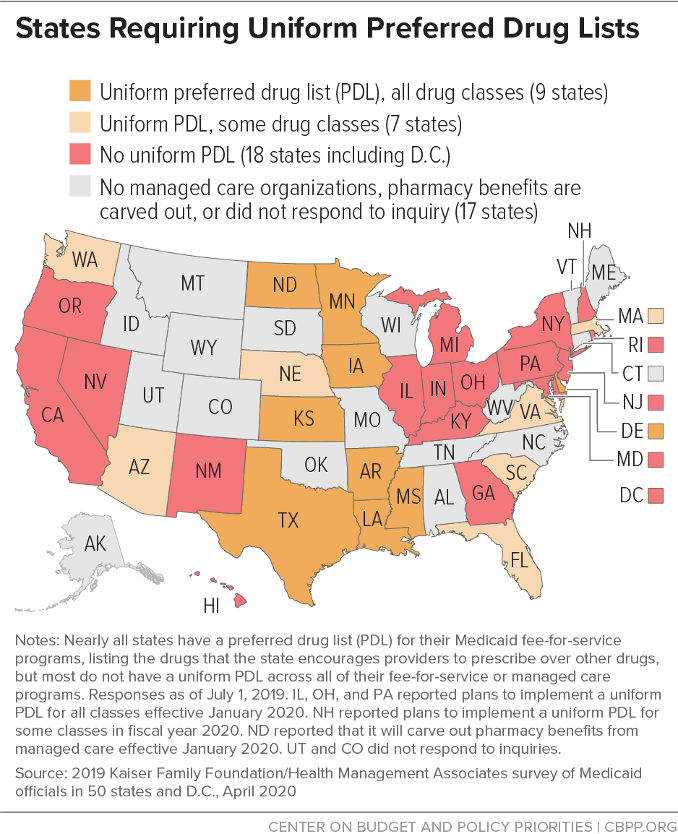

Require MCOs to adopt uniform PDLs. Nearly all states have a preferred drug list (PDL) in place for their fee-for-service programs. The PDL lists the drugs that the state encourages providers to prescribe over other drugs. PDLs allow states to encourage the use of lower-cost and higher-value prescription drugs, and the inclusion of a drug on the PDL provides leverage for states to negotiate deeper discounts from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Establishing a uniform PDL across fee-for-service and managed care can dramatically increase the number of prescriptions covered by the PDL, which in turn increases the state’s bargaining power with pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Sixteen states with MCOs reported having a uniform PDL for some or all drug classes, and eight states plan to establish or expand a uniform PDL in FY 2020.

- Require MCOs to adopt uniform generic substitution policies. Almost all states have policies that promote the use of generic drugs, such as requiring pharmacies to substitute a generic drug for a brand name drug when available. However, only about half of states that contract with MCOs reported that they consistently require the MCOs to align their generic substitution policies with the state’s fee-for-service requirements.

-

Alternative payment models. Some states have proposed new models of prescription drug payment with the goals of reducing costs, increasing value, and/or making prescription drug spending more predictable. For example, states are increasingly interested in prescription drug pricing models that pay more for drugs that are deemed effective in improving clinical outcomes. However, because pharmaceutical manufacturers have far more information about the effects of their products than states, states are at a disadvantage when negotiating contracts that rely on clinical effectiveness. More evaluation is therefore needed to determine whether these models achieve their goals.

Six states (Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Oklahoma) have outcomes-based pricing arrangements, where manufacturers’ supplemental rebate for certain prescription drugs varies based on patients’ clinical outcomes.

Two states (Louisiana and Washington) have subscription models for costly hepatitis C drugs, allowing them to pay a set amount to a manufacturer in return for supplying as much of the drug as Medicaid enrollees are prescribed. This arrangement in effect provides a supplemental rebate to the state that offsets the total cost of the drug after the state purchases a certain quantity.