The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has extended health coverage to over 20 million people and has lowered the cost of coverage or care for millions more. But a frequent criticism of the law is that it has not done enough to make coverage affordable for middle-income individual market consumers. The solution to this problem is straightforward. Increasing or eliminating the income cap on the ACA’s premium tax credits would ensure that nearly all consumers have coverage options that cost less than 10 percent of their incomes. (A companion CBPP analysis discusses policies to make coverage more affordable for low- and moderate-income people, who still face the greatest affordability challenges and the highest uninsured rates.[1])

About 6 million people purchase individual market plans without premium tax credits, and another 4 to 5 million people with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies are uninsured. Discussions about how to help these consumers are often unduly focused on sticker price premiums. A common assumption is that premiums in the ACA individual market are exceptionally high relative to other health insurance markets, and that solving this problem requires structural change to the ACA.

In fact, as of 2017 — after insurers raised premiums to bring them in line with costs and achieve sustainable margins, but before Trump Administration actions that further increased premiums — ACA individual market premiums were roughly in line with premiums for employer plans with similar cost sharing (although individual market plans often had narrower networks). But in the individual market, middle-income consumers generally receive no tax subsidies and pay their entire premium out of their take-home pay. In contrast, middle-income people with employer coverage receive substantial tax subsidies and often have much of their premium paid by their employer.

Under the ACA, people with incomes below 400 percent of the federal poverty line (about $50,000 for a single person or $100,000 for a family of four) are eligible for premium tax credits that make up the difference between premiums and a set percentage of income (for example, 9.86 percent for people with incomes between 300 and 400 percent of the poverty line). But people with incomes above 400 percent of the poverty line are not eligible for financial help, regardless of how high their premiums are as a share of their incomes. Extending premium tax credits to people at higher income levels would make net premiums more affordable for middle-income consumers. It would do so by subsidizing their coverage by amounts that would be likely be similar to or less than the tax benefits that middle-income people with employer plans get, on average.

Expanding eligibility for premium tax credits is better for both consumers and the individual market as a whole than other commonly discussed approaches to making coverage more affordable for middle-income people.

- It is significantly more targeted than subsidizing premiums though a federal reinsurance program. A similar-cost reinsurance program would provide substantially less help to middle-income people, while subsidizing coverage for high-income people by thousands of dollars. It would also provide less help to older people and people in high-cost areas. And a reinsurance program would offer consumers, and the market as a whole, less protection against future adverse cost shocks.

- It would make coverage more affordable for both healthy and sick people with incomes above 400 percent of the poverty line, unlike the Administration’s preferred alternative of expanding access to plans exempt from ACA consumer protections. Expanding access to non-ACA plans reduces premiums for healthy people at the expense of higher premiums for people with pre-existing conditions and others who need comprehensive coverage. Meanwhile, because those plans often exclude critical services and impose annual limits on coverage, people purchasing them may face catastrophic costs if they get sick.

Eliminating the income cap on premium tax credits would reduce premiums for middle-income people already purchasing individual market coverage and would lead 1.7 million additional people to gain coverage, at a cost of about $10 billion per year, according to estimates by RAND Corporation researchers.[2] Rolling back the Administration’s expansion of non-ACA plans could help cover part of the cost, since that expansion will increase federal spending by billions of dollars over the coming decade (as explained below). Offsets could also include a range of Medicare payment reforms included in both the Trump and Obama budgets; creating a public option that would put downward pressure on ACA individual market prices, which would reduce federal costs for premium tax credits for those already eligible; and/or rolling back even a modest portion of the 2017 tax bill, which will cost nearly $2 trillion over 10 years.

Notably, the 2017 tax bill cut $314 billion over ten years from health programs by repealing the ACA’s individual mandate penalty, leading fewer people to sign up for subsidized coverage. Undoing tax cuts worth that amount could pay for both extending premium tax credits to people with higher incomes and improving tax credits for people with lower incomes.

Discussions about affordability challenges for middle-income individual market consumers often start from the assumption that premiums in the ACA individual market are far higher than in other health insurance markets due to severe adverse selection.[3] This impression was reinforced by large premium increases in 2017 (prior to Trump Administration actions weakening the ACA).

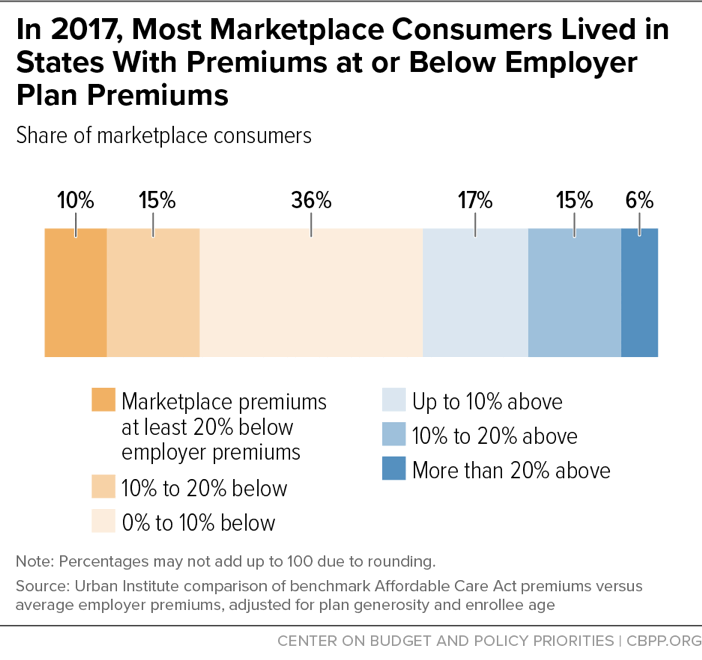

But in fact, as of 2017 — after these premium increases — ACA individual market premiums were roughly in line with premiums for employer coverage with similar out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, co-pays, and co-insurance), a reasonable proxy for the cost of providing private coverage to a broad cross-section of the population. For example, about 60 percent of ACA marketplace consumers lived in states where benchmark premiums for ACA coverage were below or equal to employer premiums, and another 17 percent lived in states where they were no more than 10 percent higher, according to an Urban Institute analysis.[4] (See Figure 1.) Individual market plans often have narrower networks than employer plans, which lowers prices, and so similar premiums indicate that the individual market risk pool was likely modestly weaker, on average.[5] But the data contradict claims that healthy people have largely exited the ACA marketplaces or that the structure of the ACA inherently leads to very high premiums.[6]

Meanwhile, the 2017 individual market premium increases brought premiums in line with costs, generating sustainable margins for individual market insurers.[7] That suggests that premiums would likely have stabilized at these levels (that is, grown with economy-wide medical trends, keeping pace with employer premiums) if not for subsequent policy actions undermining the ACA.[8]

After the ACA’s major individual market reforms took effect in 2014, per-person costs in the individual market quickly caught up with per-person costs in the large group and self-insured employer markets, data from a large medical claims database show. But after that, growth in per-person individual market costs largely tracked cost growth in the employer market.[9] As noted above, individual market premiums caught up with employer premiums a couple years later, in 2017, as insurers learned to price for a dramatically altered market (and after the ACA’s temporary reinsurance program phased out).

Since 2017, Administration and congressional actions (for example, the Administration’s cuts to outreach and advertising; its expansion of non-ACA plans, discussed below; and the repeal of the ACA’s individual mandate penalty) have weakened the ACA individual market risk pool and increased premiums relative to employer plans. Reversing these actions would reverse these increases. Proposals to introduce a public plan in the ACA marketplaces, with hospital and physician payment rates linked to Medicare payment rates, could reduce costs and premiums more significantly.[10] ACA individual market premiums are unlikely to fall far below premiums for comparable employer coverage, however, since both are driven by the same trends in health care utilization and provider prices. This limits how much policies can realistically reduce ACA individual market premiums, absent larger changes that reduce health care prices and costs systemwide.

Even when premiums are similar, individual market plans are generally less affordable for middle-income consumers than employer plans. Employees typically pay only a portion of premiums out of pocket, with their employers paying the rest.[11] In addition, middle-income families with employer coverage receive a tax subsidy averaging over $5,000, covering close to 40 percent of premiums.[12]

In contrast, the roughly 6 million individual market consumers with incomes too high to qualify for premium tax credits pay the full sticker price of their plans out of pocket.[13] The result is that some middle-income individual market consumers — especially those with incomes only modestly above 400 percent of the poverty line, those who are older, and those who live in high-cost areas — face premiums that exceed 15 or even 20 percent of their income.[14]

A straightforward solution to making coverage more affordable for middle-income consumers would be to make them eligible for the ACA’s premium tax credits. For people with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line, premium tax credits are calculated as the difference between sticker price premiums for the benchmark plan (the second-lowest-cost silver plan available in their area) and a set share of income — for example, 9.86 percent of income for people with incomes between 300 and 400 percent of the poverty line.[15] Premium tax credits cover the remaining cost of the plan.

If the cap on premium tax credits at 400 percent of the poverty line were eliminated, with no other changes, individual market consumers at all income levels would receive subsidies if their premiums exceeded 9.86 percent of income.[16] This structure has a number of desirable features.

- Middle-income people would receive the most help from the change, while premium tax credits would automatically phase out at higher income levels. For example, marketplace benchmark coverage costs an average of $18,352 for a family of four.[17] For a family with income of $101,000 (just above 400 percent of the poverty line), that amounts to 18.17 percent of income. If the income limit on premium tax credits were lifted, a family facing the national average premium would therefore receive a premium tax credit of $8,393 ($18,352 – 9.86%*$101,000). A family with income of $150,000 would receive a premium tax credit of $3,562, while a family with income of $187,000 or higher would not receive a tax credit, because the sticker price premium is less than 9.86 percent of their income.

- Older people would receive more help than younger people at the same income levels because younger people have lower sticker price premiums. (Younger people also tend to have lower incomes.) For example, marketplace benchmark coverage costs an average of $12,190 for a 60-year-old, compared to $6,486 for a 45-year-old, and $5,098 for a 30-year-old. A 60-year-old making $50,000 per year (just above 400 percent of the poverty line) and facing the national average premium would thus receive a premium tax credit of $7,260, compared to $1,556 for a 45-year-old and $168 for a 30-year-old.

- People in areas with high health care costs and high premiums would receive more financial help than people in lower-cost areas. For example, for a single 45-year-old adult, the annual benchmark premium is $10,790 in Cheyenne, Wyoming (which has among the highest premiums in the country) compared to $4,181 in Boston, Massachusetts (which has among the lowest). Such a consumer making $50,000 per year would qualify for a premium tax credit of $4,930 in Cheyenne but would not qualify for a premium tax credit in Boston.

-

Like other subsidized consumers, middle-income people could use their premium tax credits to buy plans that cost less than the benchmark, lowering their net premiums. The Trump Administration’s decision to stop paying cost-sharing reductions has led premiums for benchmark coverage to increase substantially relative to premiums for bronze (higher deductible) or gold (lower deductible) plan coverage. As a result, many consumers would be able to find bronze plans that cost considerably less than 9.86 percent of income, and gold plans that cost about that amount.

For example, the 2019 premium for the lowest-cost gold plan is less than or similar to the premium for the benchmark silver plan in 21 of 51 cities examined in a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis, meaning that families could purchase gold plans for about 9.86 percent of income (or less). Meanwhile, in 40 of 51 cities, the family of four earning $101,000 could purchase a bronze plan for less than 7 percent of income.[18]

- The average federal tax subsidy for individual market consumers would likely be similar to the average subsidy for people at the same income levels with employer coverage. Treasury data show that the average federal tax subsidy per person with employer coverage who has income between 400 and 600 percent of the poverty line is about $2,500 (about $5,000 per family). The average premium tax credit per person with marketplace coverage would almost certainly be similar to or less than that amount.[19]

Eliminating the cap on premium tax credits at 400 percent of the poverty line would also address other problems. Currently, people who expect to fall below 400 percent of the poverty line but are pushed just above it by unexpected income, such as a year-end bonus, must repay their entire premium tax credit. That means a small change in income can result in very large repayment obligations. If the income cap on premium tax credits were eliminated, a person’s premium tax credit would fall when their income rose, but he or she wouldn’t lose eligibility for premium tax credits altogether. Someone whose income unexpectedly increased by $1,000, for example, would usually owe no more than $98.60 back, rather than potentially thousands of dollars.[20]

Also important, eliminating the income cap on premium tax credits would help protect the individual market risk pool as a whole against future unexpected cost shocks. Suppose premiums unexpectedly rise by 10 percent, for example due to a future Trump Administration policy that causes healthier people to exit the market. Premium tax credits would expand as needed to ensure that all consumers still had plan options costing less than 9.86 percent of income. This automatic adjustment not only protects consumers; it also protects the risk pool by preventing additional healthy people from dropping coverage due to rising premiums. The availability of premium tax credits to people with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line already prevents premium increases from causing significant deterioration in the ACA risk pool, but extending tax credits to all income levels would make the market even more robust.[21]

Some have raised concerns about the impact of extending premium tax credits in markets with limited competition. As the textbox below explains, there are already checks in place to address this concern, and additional policies could be adopted.

A commonly discussed alternative approach to making coverage more affordable for middle-income people is a reinsurance program, which would reimburse insurers for some of the costs associated with high-cost enrollees.

Like eliminating the income cap on premium tax credits, establishing a federal reinsurance program, or providing federal funding for state reinsurance programs, would reduce premiums for consumers by investing additional federal dollars. Also like extending premium tax credits, reinsurance would provide help almost exclusively to people who aren’t currently eligible for subsidies.[22]

But as a way of directing help to these consumers, reinsurance has two significant disadvantages compared to extending tax credits.

First, the assistance it provides is significantly less targeted. Where extending premium tax credits would guarantee all consumers at least one coverage option that costs less than 10 percent of their incomes, a similar-cost, permanent federal reinsurance program would reduce premiums by about 25 percent across the board.[23] That means:

-

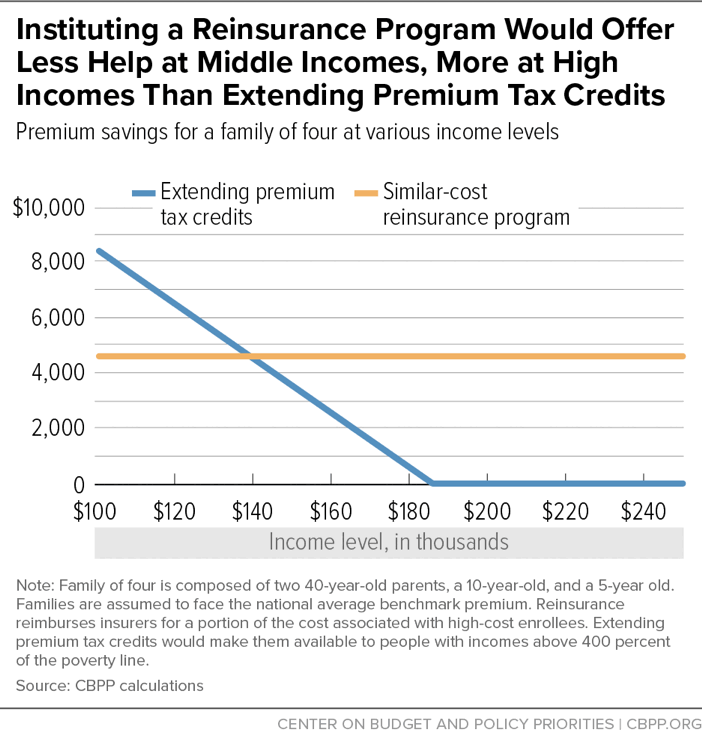

Reinsurance would skew toward higher-income people, providing less help to people just above 400 percent of the poverty line and more to those at much higher income levels. For example, premium tax credits would offer more help than reinsurance to the family of four described in the example above up to an income level of $140,000. A reinsurance program would provide a subsidy exceeding $4,000 even to families earning $200,000 or more. (See Figure 2.)

But middle-income families need more help affording coverage. In addition to facing higher premium burdens as a share of income, middle-income families are more likely to be uninsured than those at higher income levels. For example, the uninsured rate for people from 400 to 500 percent of the poverty line is 6.0 percent, compared to 3.2 percent for people above 500 percent of the poverty line.

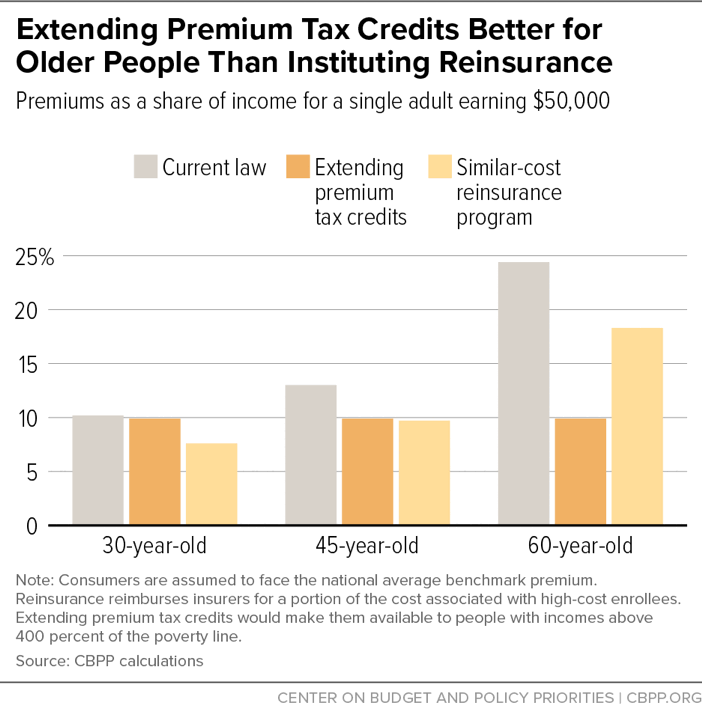

- Reinsurance would help older people less, and younger people with lower premiums more. As a result, typical middle-income older people would still face high premium burdens as a share of income. (See Figure 3.)

- Reinsurance would provide less help to people in high-cost areas. Where extending premium tax credits would guarantee consumers in all states plan options costing 9.86 percent of income or less, under a similar-cost reinsurance program, benchmark premiums for a family of four earning $101,000 would exceed 15 percent of income in 14 of the 51 cities examined in the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis.

The same dynamics carry through to lower-cost versions of both reinsurance and enhanced tax credits. For example, one congressional proposal would increase the income limit on premium tax credits, rather than eliminate it, and both that proposal and a recent proposal from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association would eliminate the income limit but require people at higher incomes to pay more than 10 percent of income toward benchmark premiums.[24] Compared to similar-cost reinsurance programs, these proposals would also target more resources toward middle-income people, older people, and people in high-cost areas.

Second, reinsurance offers consumers and the individual market as a whole less protection against future adverse cost shocks. Some reinsurance programs involve capped funding amounts, meaning the subsidy they provide would not grow at all in response to higher-than-expected health care costs. And even a reinsurance program that reimburses a fixed percentage of costs above some threshold would buffer only a portion of an unexpected cost shock. That means that premiums would still increase for consumers with incomes above 400 percent of the poverty line, and some disproportionately healthy consumers would drop coverage as a result, hurting the individual market risk pool. In contrast, as explained above, extending premium tax credits means that most consumers above 400 percent of the poverty line would be fully protected from adverse cost shocks, just as consumers with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line are today.

The Administration’s proposed solution to the affordability challenges facing middle-income consumers is to allow more of them to purchase non-ACA plans. Most significant, the Administration is permitting so-called “short-term, limited duration” plans, previously limited to three months, to instead be issued for up to one year and to be renewed. These plans can deny coverage or charge higher premiums based on health status, impose annual and lifetime limits on coverage, and exclude essential health benefits. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma has touted these plans as the Administration’s solution for people with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies, commenting, “This final rule [expanding short-term plans] opens the door to new, more affordable coverage options for millions of middle-class Americans who have been priced out of ACA plans.”[25]

Short-term plans do offer healthy people lower premiums. But they do so by denying coverage to sicker people and by excluding coverage for various benefits, such as maternity care and prescription drugs. (A Kaiser Family Foundation survey of short-term plans offered in 2018 found that none covered maternity care, fewer than a third covered prescription drugs, and fewer than half covered treatment for substance use disorders.[26]) As a result, these plans’ savings come at the expense of two groups. First, because these plans pull healthy people out of the ACA individual market, they raise premiums for people who remain in these markets, including middle-income people with pre-existing conditions. Second, initially healthy people who enroll in these plans but then experience illness or injury can find themselves exposed to catastrophic costs. Consumers are unlikely to fully understand these plans’ limitations and often will not appreciate their significance unless and until they get sick.[27]

Lower-income consumers are protected from the higher premiums resulting from the Administration’s expansion of short-term plans because, as explained above, premium tax credits increase automatically in response to premium increases. Because of these tax credit increases, the expansion of short-term plans will cost the federal government billions of dollars over ten years, according to the Administration’s own estimates.[28] By rolling back the short-term plans rule, policymakers could redirect these dollars to help pay for lifting the income limit on ACA subsidies. That would help middle-income people — those who are healthy and also those who are not — afford comprehensive coverage.

One concern about eliminating the income cap on premium tax credits is that doing so could raise (sticker price) premiums in markets with limited competition. The worry is that, if a larger share of consumers were eligible for premium tax credits that adjust based on changes in benchmark premiums, a monopoly insurer could increase the benchmark premium dramatically without losing significant enrollment.a

But several checks are in place to address this concern. Most important, an overpriced market will eventually attract competitors. Consistent with that, after many insurers set premiums above costs for 2018, new insurers entered many overpriced markets in 2019, increasing the average number of insurers from three to four in HealthCare.gov states.b In addition:

- Even if the income limit on premium tax credits were lifted, high-income consumers generally still wouldn’t qualify for subsidies because sticker price premiums would be less than 9.86 percent of their incomes.

- As a result of the ACA, individual market insurers are required to spend at least 80 cents of every dollar in premium revenue on medical costs (versus administrative costs and profits), or to rebate excess profits to consumers. This limits insurers’ incentives to exploit market power in setting premiums.

- Also under the ACA, state regulators review individual market premiums and are generally empowered to challenge premiums that are not in line with costs.

- Finally, if policymakers are still concerned about the risks associated with low-competition markets, they could pair eliminating the income limit on premium tax credits with the introduction of a public plan in the ACA marketplaces, either nationwide or as a backstop in markets with limited insurer and provider competition. As noted above, a public plan would also generate federal savings that could help pay for extending and improving premium tax credits.

Moreover, concerns about impacts on sticker price premiums are not a reason to prefer a reinsurance program to extending premium tax credits. Under a reinsurance program, insurers pay only a portion of the cost of certain high-cost claims — 20 percent or less under several state programs. By insulating insurers from a large fraction of the cost of expensive care, reinsurance can reduce their incentive to keep costs down, particularly by negotiating rates with hospitals and other providers. This could increase premiums across both low- and high-competition markets.

a Provided there are multiple insurers in a market, they have strong incentives to keep premiums low even if virtually all consumers receive premium tax credits. That’s because, while premium tax credits insulate consumers from across-the-board premium increases, they still pay the full difference between the benchmark premium and the plan they select (or pay less if they choose a plan cheaper than the benchmark). Thus, insurers will still gain or lose business based on how they price relative to their competitors.

b Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “2019 Health Plan Choice and Premiums in HealthCare.gov States,” Department of Health and Human Services, October 26, 2018, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/260041/2019LandscapeBrief.pdf.