Latest Version of Cassidy-Graham Still Has Damaging Cuts to Health Care Funding That Grow Dramatically in 2027

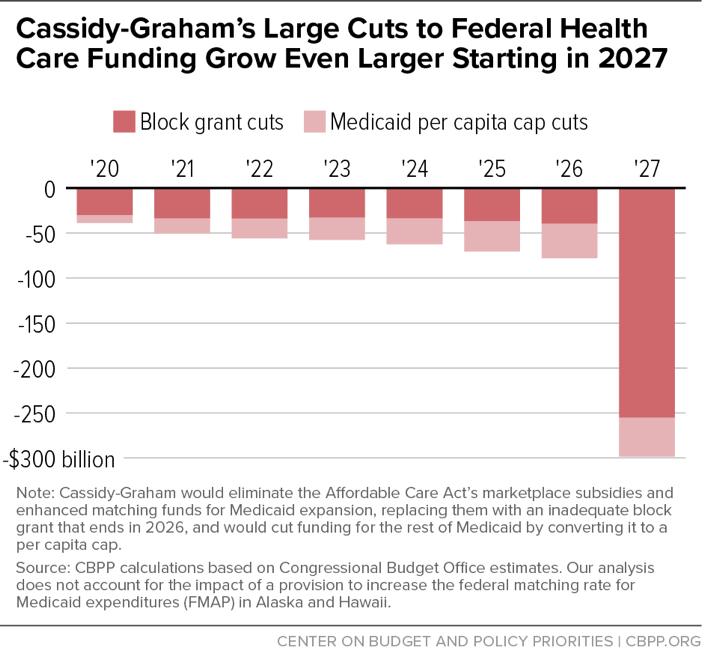

Like prior versions, the latest version of the bill from Senators Bill Cassidy and Lindsey Graham to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would cut federal funding for health coverage for the large majority of states over the next decade (see Table 1). And the cuts would grow dramatically in 2027, when the bill’s temporary block grant (which would replace the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies) would expire and its Medicaid per capita cap cuts would become increasingly severe. We estimate that in 2027 alone, the bill would cut federal health care funding by $298 billion relative to current law (see Figure 1), with the cuts affecting all states.

Starting in 2027, Cassidy-Graham would likely be even more damaging than a straight repeal-without-replace bill. In fact, starting in 2027, Cassidy-Graham would likely be even more damaging than a straight repeal-without-replace bill because it would add large cuts to the rest of Medicaid — on top of eliminating the Medicaid expansion — by imposing a per capita cap on the entire program. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has previously estimated that the repeal-without-replace approach would ultimately leave 32 million more people uninsured.[1] Cassidy-Graham would presumably result in even deeper coverage losses than that in the second decade as the cuts due to the Medicaid per capita cap continue to deepen.

The revised Cassidy-Graham legislation would:

- Eliminate the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and ACA’s marketplace subsidies in 2020 and replace them with an inadequate block grant. Under our estimates, the block grant would provide about $239 billion less between 2020 and 2026 than projected federal spending for the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies under current law, with the cut reaching $40 billion (16 percent) in 2026. The block grant would not adjust based on changes in states’ funding needs, and it could be spent on virtually any health care purpose, with no requirement to offer low- and moderate-income people coverage or financial assistance. And, as noted, the block grant would disappear altogether in 2027.

- Cap and cut federal Medicaid per-beneficiary funding for tens of millions of seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children starting in 2020. Instead of the existing federal-state financial partnership, under which the federal government pays a fixed percentage of a state’s Medicaid costs, Cassidy-Graham would cap federal Medicaid funding at a set amount per beneficiary, irrespective of states’ actual costs. The cap would grow more slowly each year than the projected growth in state per-beneficiary costs. Prior CBO estimates suggest that Cassidy-Graham would thus cut the rest of Medicaid (outside the expansion) by at least $170 billion between 2020 and 2026, with the cuts reaching at least $38 billion (8 percent) by 2026, relative to current law.[2] That would result in a combined cut to federal funding for health coverage of roughly $78 billion in 2026 (see Table 1).

These severe cuts would be even more draconian in 2027 (see Table 1). Federal funding for health coverage nationwide would be cut by roughly $298 billion in that year alone, relative to projected spending on the Medicaid expansion, marketplace subsidies, and the Medicaid program (outside of the expansion).

The enormous cut in 2027 reflects two factors. First, the block grant would disappear in 2027. The bill’s sponsors have claimed that the rules that govern the budget reconciliation process, which allows the bill to pass the Senate with only 50 votes, necessitated that the proposed block grant be temporary. In reality, however, nothing in those rules prevents the bill from permanently funding its block grant. Furthermore, the expiration of the temporary block grant would create a funding cliff that Congress likely couldn’t afford to fill. Even if there were significant political support for extending the inadequate block grant in the future, budget rules would very likely require offsets for the hundreds of billions of dollars in increased federal spending needed for each additional year.[3]

Second, the cuts from the Medicaid per capita cap would be growing much deeper because the bill would reduce the annual adjustment of the per capita cap to an even more inadequate level starting in 2025. This further cut would significantly enlarge the gap between per capita cap amounts and states’ actual Medicaid spending needs and drive severe Medicaid cuts in the second decade, as CBO has found with the Senate Republican leadership bill (the Better Care Reconciliation Act).[4]

Methods Note

We estimate each state’s federal funding block grant amount in 2026 under the parameters of the Cassidy-Graham block grant formula, and compare the result to an estimate of the state’s current-law federal funding for the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, marketplace subsidies, and/or the Basic Health Program (BHP).

To estimate states’ Cassidy-Graham block grant amounts in 2026, we first calculate each state’s base period federal spending by summing the most recent Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) spending data on the Medicaid expansion, marketplace subsidies, and BHP. We then inflate Medicaid expansion spending based on the CMS Office of the Actuary’s (OACT) estimate of spending growth through 2019, and we inflate marketplace subsidy and BHP spending based on OACT’s estimate of medical cost inflation. We also adjust base period spending for two low-population-density states with high per capita health expenditures: Alaska and North Dakota. We then use the most recent population data from the American Community Survey (ACS) to estimate for each state the number of individuals with family income between 50 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty line.

States’ block grant amounts from 2020 through 2026 are calculated based on the scheduled phase-in under the legislation, from amounts based on a state’s base period spending to amounts based on a state’s share of the national population between 50 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty line. We account also for the bill’s 25 percent limit on annual growth in a state’s block grant amount; for additional funds available to Louisiana and Montana, which expanded Medicaid to low-income adults after December 31, 2015; and for additional funds to Alaska and Hawaii, which have implemented Section 1332 waivers.

To estimate federal funding for the ACA’s major coverage expansions under current law, we start with CBO’s March 2016 projections of national-level spending on the Medicaid expansion, marketplace subsidies, and/or BHP in 2026. We adjust these projections to 2027 assuming growth between 2026 and 2027 equal to the growth in these estimates between 2025 and 2026. We apportion these amounts across the states based on CMS’ most recent state-level data on the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies.

Results of our analysis reflect two limitations. First, limited data availability requires that we apportion CBO’s national-level estimate of cost-sharing reduction payments to states based on states’ premium tax credit amounts rather than cost-sharing reduction amounts. Second, CBO’s projection of Medicaid expansion spending in 2026 assumes that additional states (beyond the current 31 states and the District of Columbia) take up the expansion, but CBO does not project which specific states would do so.

Figures in Table 1 reflect the combined impact of the elimination of the Cassidy-Graham block grant and the Cassidy-Graham Medicaid per capita cap. In its cost estimate for the Senate GOP leadership’s health bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), CBO estimates the federal Medicaid spending cut outside of the expansion due to the per capita cap. We interpolate, based on other CBO per capita cap estimates, to adjust the BCRA estimate to account for both Cassidy-Graham’s changes to the per capita cap annual adjustment rate (relative to the BCRA) and the plan’s exclusion of certain low-population-density states from the per capita cap. Again, we adjust this per capita cap cut projection to 2026 and 2027 assuming growth between 2025 and 2026, and between 2026 and 2027, equal to the 2024-to-2025 growth in this estimate. We apportion this national cut estimate in 2026 and 2027 to states based on the Kaiser Family Foundation’s state-specific estimates of the federal funding impact of the BCRA’s per capita cap.

We do not account for the Cassidy-Graham provision that restores disproportionate share hospital federal funding to states in which the block grant does not grow annually at the rate of medical cost inflation. Nor do we account for the provision that limits states’ ability to charge provider taxes to support Medicaid spending. The revised Cassidy-Graham legislation also increases the federal matching rate (FMAP) for Alaska and Hawaii. We are unable at this time to produce specific estimates of the combined impact of the legislation’s block grant and per capita cap provisions for these two states because of their interaction with the FMAP provision. Analysis of the impact of the block grant and per capita cap provisions separately suggest that federal funding reductions related to the block grant and per capita cap provisions would more than offset any federal funding increases related to the FMAP provisions as early as 2026 in Hawaii and as early as 2027 in Alaska.

| TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cassidy-Graham Block Grant and Medicaid Per Capita Cap Would Cut Federal Funding for All States by 2027 | ||||||

| State | Estimated federal funding change, in 2026 (in $millions) | Estimated federal funding change, in 2027 (in $millions) | ||||

| Alabama | 1,026 | -2,151 | ||||

| Alaska | * | * | ||||

| Arizona | - 1,732 | - 6,913 | ||||

| Arkansas | - 1,012 | - 3,912 | ||||

| California | - 23,063 | - 57,548 | ||||

| Colorado | - 771 | - 3,842 | ||||

| Connecticut | - 1,930 | - 4,054 | ||||

| Delaware | - 648 | - 1,277 | ||||

| District of Columbia | - 532 | - 867 | ||||

| Florida | - 3,528 | - 17,801 | ||||

| Georgia | 674 | -5,731 | ||||

| Hawaii | * | * | ||||

| Idaho | 39 | -987 | ||||

| Illinois | - 1,454 | - 9,264 | ||||

| Indiana | - 677 | - 4,850 | ||||

| Iowa | - 499 | - 2,334 | ||||

| Kansas | 493 | -912 | ||||

| Kentucky | - 2,511 | - 6,890 | ||||

| Louisiana | - 1,525 | - 7,277 | ||||

| Maine | - 191 | - 1,037 | ||||

| Maryland | - 1,827 | - 4,887 | ||||

| Massachusetts | - 4,592 | - 8,717 | ||||

| Michigan | - 2,761 | - 10,000 | ||||

| Minnesota | - 2,407 | - 5,718 | ||||

| Mississippi | 870 | -1,284 | ||||

| Missouri | 52 | -3,423 | ||||

| Montana | - 307 | - 1,346 | ||||

| Nebraska | 69 | -922 | ||||

| Nevada | - 583 | - 2,701 | ||||

| New Hampshire | - 355 | - 948 | ||||

| New Jersey | - 3,260 | - 8,548 | ||||

| New Mexico | - 1,140 | - 3,445 | ||||

| New York | - 17,196 | - 33,059 | ||||

| North Carolina | - 1,626 | - 8,709 | ||||

| North Dakota | - 205 | - 676 | ||||

| Ohio | - 2,372 | - 10,259 | ||||

| Oklahoma | 619 | -1,698 | ||||

| Oregon | - 2,911 | - 6,576 | ||||

| Pennsylvania | - 1,200 | - 8,264 | ||||

| Rhode Island | - 523 | - 1,300 | ||||

| South Carolina | 300 | -2,786 | ||||

| South Dakota | 89 | -313 | ||||

| Tennessee | 813 | -3,203 | ||||

| Texas | 4,683 | -11,947 | ||||

| Utah | 101 | -1,280 | ||||

| Vermont | - 505 | - 920 | ||||

| Virginia | -145 | -3,833 | ||||

| Washington | - 2,758 | - 7,541 | ||||

| West Virginia | - 513 | - 2,042 | ||||

| Wisconsin | -91 | -2,909 | ||||

| Wyoming | -124 | -386 | ||||

* The revised Cassidy-Graham legislation also increases the federal matching rate (FMAP) for Alaska and Hawaii. We are unable at this time to produce estimates of the combined impact of the legislation’s block grant and per capita cap provisions for these two states because of their interaction with the FMAP provision. Analysis of the impact of the block grant and per capita cap provisions separately suggest that federal funding reductions related to the block grant and per capita cap provisions would more than offset any federal funding increases related to the FMAP provision as early as 2026 in Hawaii and as early as 2027 in Alaska. Source: CBPP analysis, see methods notes for details.

Cassidy-Graham’s Waiver Authority Would Gut Protections for People with Pre-Existing Conditions

Policy Basics

Health

End Notes

[1] Edwin Park, “CBO: 32 Million People Would Lose Health Coverage Under ACA Repeal,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/cbo-32-million-people-would-lose-health-coverage-under-aca-repeal.

[2] See Jacob Leibenluft et al., “Like Other ACA Repeal Bills, Cassidy-Graham Plan Would Add Millions to Uninsured, Destabilize Individual Market,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised September 20, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/like-other-aca-repeal-bills-cassidy-graham-plan-would-add-millions-to-uninsured.

[3] David Kamin and Richard Kogan, “Cassidy-Graham’s Dramatic Funding Cliff Not Required by Budget Rules and Would Have Lasting, Negative Impact,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 20, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/cassidy-grahams-dramatic-funding-cliff-not-required-by-budget-rules-and-would-have.

[4] Congressional Budget Office, “Longer-Term Effects of the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 on Medicaid Spending,” June 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52859-medicaid.pdf. See also Edwin Park, “CBO: Senate Bills Cut Medicaid by More than One-Third by 2036,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 29, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/cbo-senate-bill-cuts-medicaid-by-more-than-one-third-by-2036.

More from the Authors