Expanding Health Savings Accounts Would Boost Tax Shelters, Not Access to Care

End Notes

[1] For example, H.R. 107 would no longer require an HSA to be paired with a high-deductible health plan and would increase the annual contribution limits: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/107. Another bill would allow gym memberships and fitness equipment to qualify as HSA expenses: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/786.

[2] U.S. Treasury Department, fiscal year 2024 tax expenditures estimates, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/tax-policy/tax-expenditures.

[3] IRS, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-22-24.pdf. Deductibles are an amount the enrollee must pay on their own before the plan begins covering most services.

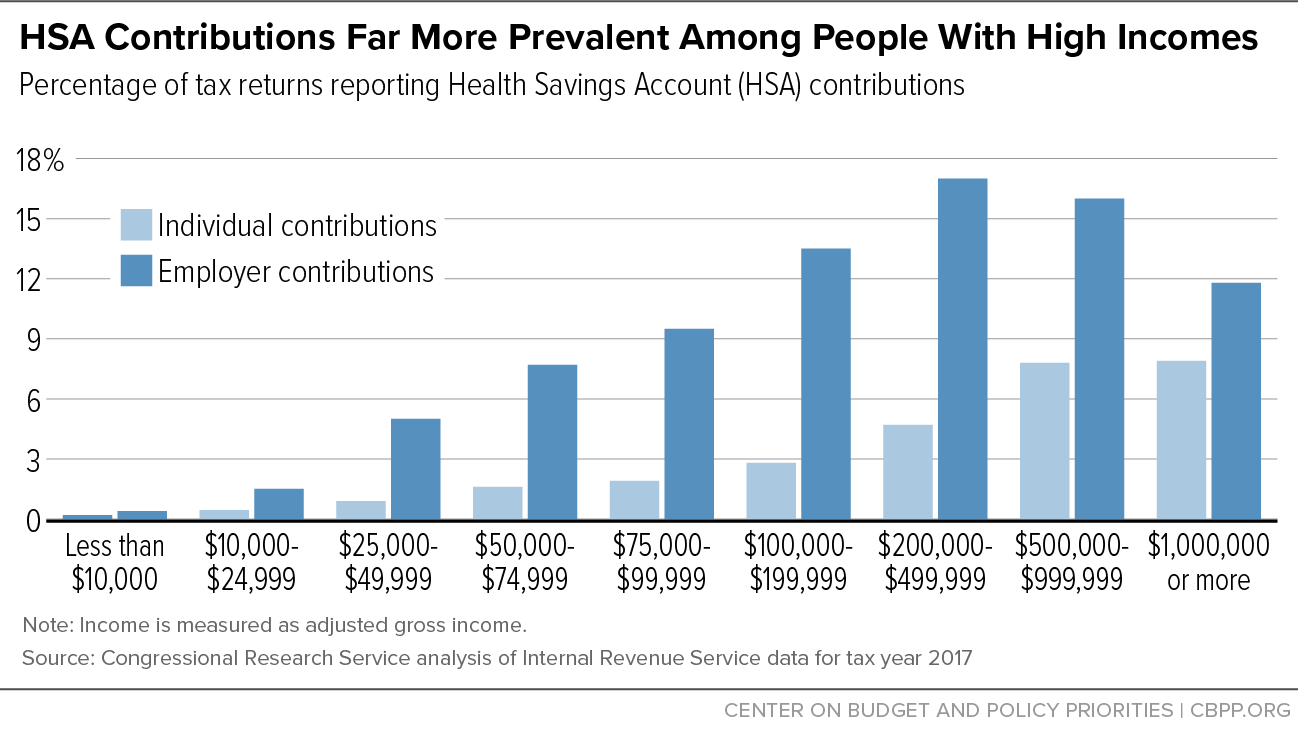

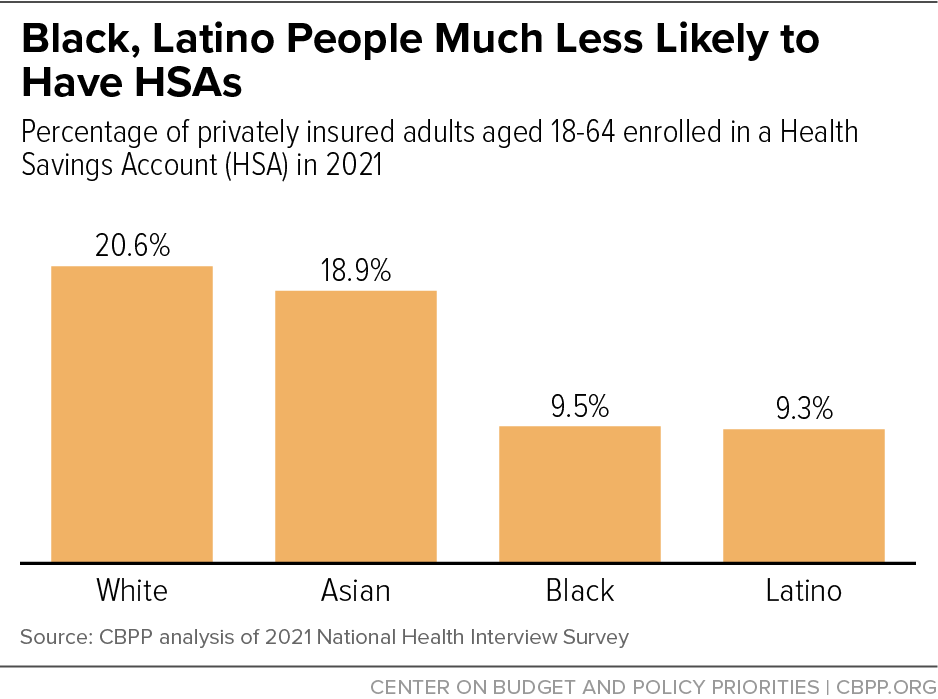

[4] CBPP analysis of 2021 National Health Interview Survey.

[5] Individual contributions to HSAs could include HSA-qualified plans that are employment-based or plans directly purchased on the individual market. Ryan Rosso, “Health Savings Accounts (HSAs),” Congressional Research Service, August 8, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45277.

[6] Ramsey Solutions, “How to Make the Most of Your HSA Investment,” December 15, 2022, https://www.ramseysolutions.com/insurance/hsa-investment.

[7] Devenir, “HSA Assets Hit $100 Billion Milestone,” March 23, 2022, https://www.devenir.com/hsa-assets-hit-100-billion-milestone.

[8] The contribution limit for 401(k) plans in 2023 is $22,500, and people aged 50 and older can contribute an additional $7,500 in catch-up contributions. Over 5.1 million people (roughly 3 percent of the workforce) maximized their elective retirement contributions in 2018. See https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/401k-limit-increases-to-22500-for-2023-ira-limit-rises-to-6500 and IRS W-2 Tabulations Table 2.G: https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-information-return-form-w2-statistics.

[9] Ryan Ermey, “This savings account offers a ‘triple tax benefit’ — but 88% of users are missing out,” CNBC, February 9, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/02/09/health-savings-accounts-how-to-save-for-retirement.html.

[10] IRS, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-22-24.pdf.

[11] HSAs cannot be used to pay for expenses incurred before the HSA was established.

[12] Maria Hoffman, Mark Klee, and Briana Sullivan, “New Data Reveal Inequality in Retirement Account Ownership,” U.S. Census Bureau, August 31, 2022, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/08/who-has-retirement-accounts.html; U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Income and Wealth Disparities Continue through Old Age,” August 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-587.pdf.

[13] Sara Collins, Lauren Haynes, and Relebohile Masitha, “The State of U.S. Health Insurance in 2022: Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey,” Commonwealth Fund, September 29, 2022, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/sep/state-us-health-insurance-2022-biennial-survey.

[14] Caroline Ratcliffe et al., “Perceived Financial Preparedness, Saving Habits, and Financial Security,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, September 2020, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_perceived-financial-preparedness-saving-habits-and-financial-security_2020-09.pdf.

[15] Collins, Haynes, and Masitha, op cit.

[16] CBPP analysis of 2021 American Community Survey.

[17] Median household income was about $71,000 in 2021. Jessica Semega and Melissa Kollar, “Income in the United States: 2021,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 13, 2022, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-276.html.

[18] IRS, “IRS provides tax inflation adjustments for tax year 2023,” October 18, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-provides-tax-inflation-adjustments-for-tax-year-2023.

[19] KFF, “2022 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” October 27, 2022, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2022-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

[20] Lorens Helmchen et al., “Health Savings Accounts: Growth Concentrated Among High-Income Households and Large Employers,” Health Affairs, September 2015, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/epdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0480.

[21] Neil Bhutta et al., “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 28, 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.html.

[22] See https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/. Similarly, in an earlier estimate, the Congressional Budget Office projected that permanently closing the Medicaid coverage gap by extending ACA marketplace subsidies would cost $180 billion from 2022 to 2031: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-12/57673-BBBA-GrahamSmith-Letter.pdf.

[23] Sarah Lueck, “Health Bills Headed for a Vote in the House Undermine Consumer Protections and Market Rules,” CBPP, June 20, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/health-bills-headed-for-a-vote-in-the-house-undermine-consumer-protections-and-market-rules.

[24] Description of H.R. 1843, The “Telehealth Expansion Act of 2023,” Joint Committee on Taxation, June 5, 2023, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2023/jcx-12-23/.