Infant Formula Shortage Highlights WIC’s Critical Role in Feeding Babies

End Notes

[1] In 2018, WIC accounted for an estimated 56 percent of infant formula consumption. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, “Infants in USDA’s WIC Program consumed an estimated 56 percent of U.S. infant formula in 2018,” May 23, 2022, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=103970.

[2] Steven Carlson and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for More Than Four Decades,” CBPP, updated January 27, 2021, www.cbpp.org/wicworks.

[3] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “About the WIC Program,” May 12, 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/state-agency.

[4] Ibid. While geographic state agencies serve the vast majority (97 percent in fiscal year 2021) of WIC participants, territories or tribal organizations can serve as state agencies operating the WIC program.

[5] Larger states or alliances are required to conduct separate competitive bids for milk-based and soy-based formula.

[6] 7 C.F.R. § 246.16a.

[7] U.S. Small Business Administration, “Types of contracts,” https://www.sba.gov/federal-contracting/contracting-guide/types-contracts.

[8] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, “The Infant Formula Market: Consequences of a Change in the WIC Contract Brand,” August 2011, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44900/6918_err124.pdf;

Mike Abito et al., “Demand Spillover and Inequality in the WIC Program,” presentation at 20th annual International Industrial Organization Conference, May 2022, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1fzBl3LYuqo6nw9QJulVboNFXQ6y56h6K/view; Christian A. Rojas and Hongli Wei, “Spillover Mechanisms in the WIC Infant Formula Rebate Program,” Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization, Vol. 17, No. 2, December 14, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1515/jafio-2018-0019; Yoon Y. Choi, Alexis Ludwig, and Tatiana Andreyeva, “Effects of United States WIC infant formula contracts on brand sales of infant formula and toddler milks,” Journal of Public Health Policy, Vol. 41, September 2020, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-020-00228-z.

[9] Nicole Kline, Kevin Meyers Mathieu, and Jeff Marr, “WIC Participant and Program Characteristics 2018 Food Packages and Costs,” Table ES.1, Insight Policy Research, Inc., November 2020, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICPC2018FoodPackage-1.pdf.

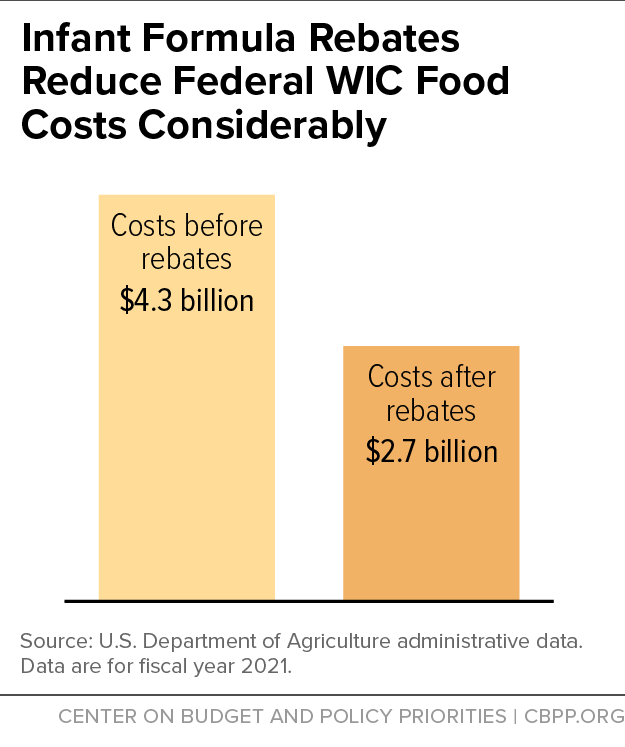

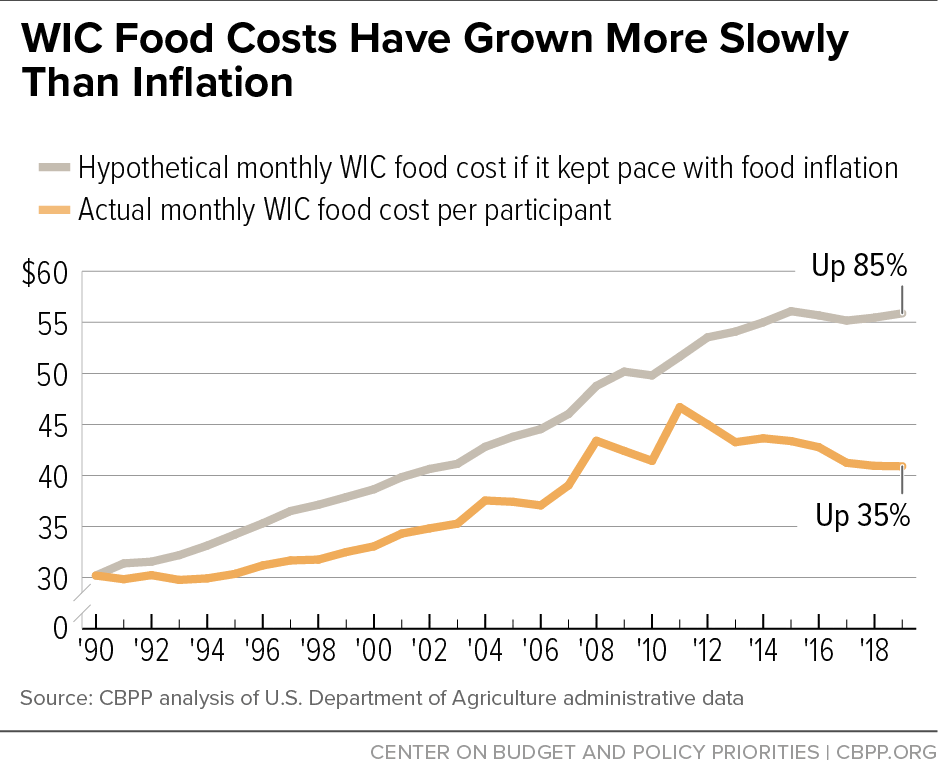

[10] The average monthly federal cost of WIC foods was $35.34 per participant in fiscal year 2021, but the average retail value of WIC foods was $56.68 per participant (excluding the increase to fruit and vegetable benefits funded through the American Rescue Plan). CBPP analysis of U.S.Department of Agriculture WIC administrative data available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program.

[11] WIC rules establish seven priority categories. In general, priority goes to persons with medically based nutrition risks over dietary-based nutrition risks, to pregnant and breastfeeding women and infants over children, and to children over postpartum women. See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(e)(4).

[12] For example, a 1990 study found that every $1 spent on the prenatal WIC program resulted in Medicaid savings of $1.77 to $3.13 for newborns and mothers in the first 60 days after birth. See “The Savings in Medicaid Costs for Newborns and Their Mothers from Prenatal Participation in the WIC Program, Volume 1,” Mathematica, October 1, 1990, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/SavVol1-Pt1.pdf. A more recent study found that spending an additional $1 on prenatal WIC in California would result in savings of $1.24 to $6.83 by reducing the risk of adverse birth outcomes. See Roch A. Nianogo, “Economic evaluation of California prenatal participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) to prevent preterm birth,” Preventive Medicine, Vol. 124, July 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0091743519301355?via%3Dihub.

[13] The enactment of the competitive bidding requirement and its aftermath is described in Steven Carlson, Robert Greenstein, and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC’s Competitive Bidding Process for Infant Formula Is Highly Cost-Effective,” CBPP, updated February 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wics-competitive-bidding-process-for-infant-formula-is-highly-cost.

[14] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, “Impact of the WIC Program on the Infant Formula Market,” January 2009, https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/catalog/32816.

[15] Ibid. Gerber is currently owned by Nestlé, but Mead Johnson also had an agreement to market Gerber-brand formula from 1989 to 1997.

[16] “Abbott retires Ross name, keeps proud tradition,” Columbus Dispatch, November 7, 2007, https://www.dispatch.com/story/business/2007/11/08/abbott-retires-ross-name-keeps/23419834007/.

[17] Pfizer, “Pfizer Completes Acquisition Of Wyeth,” Business Wire, October 14, 2009; Nestlé, “Wyeth nutrition acquisition,” https://www.nestle.com/investors/overview/mergers-and-acquisitions/wyeth-nutrition-acquisition.

[18] These and other provisions related to competitive bidding for infant formula are contained in 42 U.S.C. § 1786(h)(8)(A).

[19] The Improving Child Nutrition Integrity and Access Act (S. 3136) and Improving Child Nutrition and Education Act (H.R. 5003) were both reported out of committee in the 114th Congress but neither was considered on the floor. Both bills also included provisions requested by infant formula manufacturers regarding adjunctive eligibility for WIC. Medicaid, SNAP, and TANF monthly cash assistance payment recipients are “adjunctively eligible” for WIC, which means they are considered income-eligible and do not need to separately document their income to enroll in WIC. (See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7 (d)(2)(vi).) As the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion allowed states to extend eligibility to higher-income households, some infant formula manufacturers feared that families who would otherwise have paid full price for formula would instead receive it through WIC at the heavily discounted rate. Both bills included provisions allowing infant formula manufacturers to unilaterally terminate their WIC contract if a state increased its income eligibility limit in Medicaid in a manner that would substantially increase the number of infants served by WIC. See also Tennille Tracy, “Makers of Baby Formula Press Their Case on WIC Program,” Wall Street Journal, April 27, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/makers-of-baby-formula-press-their-case-on-wic-program-1430177799.

[20] The WIC Healthy Beginnings Act (S.3216/H.R. 7603).

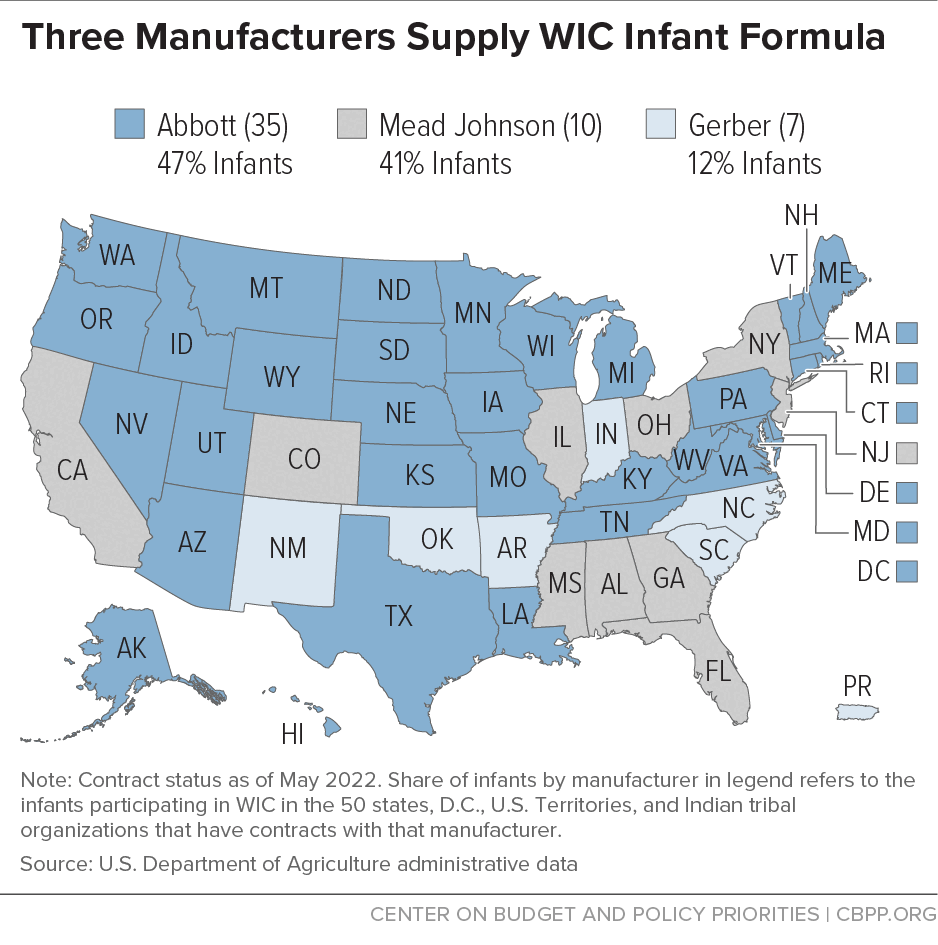

[21] In fiscal year 2012, Nestlé had contracts with 13 states with 28 percent of infants participating in WIC; Abbott had contracts with 22 states and the District of Columbia with 34 percent of infants participating in WIC; and Mead Johnson had contracts with 15 states with 38 percent of infants participating in WIC. As of May 2022, Nestlé (Gerber) had contracts with six states and Puerto Rico with 12 percent of infants participating in WIC; Abbott had contracts with 34 states and the District of Columbia with 47 percent of infants participating in WIC; and Mead Johnson had contracts with ten states with 41 percent of infants participating in WIC. (See Figure 5.) CBPP analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture and state administrative data.

[22] Food and Drug Administration, “FDA Investigation of Cronobacter Infections: Powdered Infant Formula,” February 2022, https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/fda-investigation-cronobacter-infections-powdered-infant-formula-february-2022; Michael Barbaro et al., “What Really Caused the Baby Formula Shortage,” New York Times, May 27, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/27/podcasts/the-daily/baby-formula-shortage-bacteria.html.

[23] A regularly updated summary of the federal response to the infant formula shortage is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/formula/.

[24] U.S. Department of Agriculture, “USDA Grants Additional WIC Flexibilities Amid Abbott Recall of Certain Powder Infant Formula,” February 23, 2022, https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2022/02/23/usda-grants-additional-wic-flexibilities-amid-abbott-recall-certain.

[25] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Infant Formula Safety: Infant Formula Recall & Supply,” 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/ofs/infant-formula-safety.

[26] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Letter to State Directors Regarding Infant Formula,” May 13, 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/state-director-letter-infant-formula.

[27] Links to all of these resources are available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/ofs/infant-formula-safety. The federal government’s main consumer-oriented website is https://www.hhs.gov/formula/index.html. Information for families that need specialty formula for medical reasons is available at https://naspghan.org/recent-news/naspghan-tools-for-hcps-affected-by-formula-recall/.

[28] See, for example, Stephanie Stamm, “Baby Formula Shortage Stuns States Including Tennessee, Kansas and Delaware,” Wall Street Journal, May 14, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/baby-formula-shortage-stuns-states-including-tennessee-kansas-and-delaware-11652526002.

[29] Abbott, “Abbott Restarts Production of Specialty Formulas at its Michigan Plant,” June 4, 2022, https://www.abbott.com/corpnewsroom/nutrition-health-and-wellness/abbott-update-on-powder-formula-recall.html.

[30] WIC can provide specialty formula for infants with special medical needs, sometimes referred to as “exempt” formula, but states do not receive rebates on these products from the manufacturers. State WIC agencies are also required to coordinate with the state’s Medicaid program and other potential medical payors regarding these specialty infant formulas and can only cover the cost of these formulas in situations where reimbursement is not provided by another entity. See 7 CFR § 246.10(e)(3)(vi).

[31] Food and Drug Administration, “FDA Investigation of Cronobacter Infections: Powdered Infant Formula (February 2022)”, February 2022, https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/fda-investigation-cronobacter-infections-powdered-infant-formula-february-2022.

[32] Abbott, “Abbott to Release Metabolic Nutrition Formula,” April 29, 2022; Abbott, “Abbott to Release Elecare® Amino Acid-Based Formulas to Help Meet Critical Patient Need,” May 24, 2022.

[33] The White House, “Biden Administration Approves First Operation Fly Formula Mission,” May 19, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/19/biden-administration-approves-first-operation-fly-formula-mission/.

[34] See U.S. Department of Agriculture, “USDA Offers Funding Flexibility to Help States, WIC Families Amid Infant Formula Shortages,” May 25, 2022, https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2022/05/25/usda-offers-funding-flexibility-help-states-wic-families-amid. For example, California allowed WIC participants to obtain brands, types, and container sizes of formula that they are not usually covered by WIC benefits. See California Department of Health, “100+ New Formula Options Added to the California WIC Authorized Product List,” June 2, 2022.

[35] Access to Baby Formula Act of 2022, 7791 H.R. § Text. (Pub. L. 117–129).

[36] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Additional WIC Flexibilities — Imported Infant Formula under FDA’s Infant Formula Enforcement Discretion,” June 2, 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/flexibilities-formula-enforcement-discretion.