The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) and the Child Support program both improve the health and well-being of millions of low-income children every year — SNAP by providing vital nutrition and Child Support by ensuring children receive financial support from both parents, when possible. Overlap between the two programs is strong. Nearly one-fifth of all SNAP households with children, including those with parents living together, receive child support payments.[1]

The Child Support program serves the vast majority of eligible low-income families. But some children with a parent living outside the household do not receive support from their non-residential parent. Frequently, this is because non-custodial parents are poor — not because they are unwilling to provide support to their children. Some policymakers have suggested that the best way to improve participation in the Child Support program and drive more resources to low-income children is to take away SNAP benefits from parents who do not cooperate with the Child Support program. But taking away vital food assistance from low-income families that may have good reasons not to participate in the Child Support program or are unable to make child support payments is a dangerous policy and has proven unpopular among states.

States can already condition SNAP eligibility for parents living apart on their cooperation with child support and their ability to make timely payments on child support orders. Few states have implemented these policies because they are based on flawed presumptions about the ability of sanctions to change parental behavior; there’s no evidence that they generate significantly more child support payments to custodial households; they put the food security of vulnerable people at risk, including children; implementation is very expensive and administratively complex; and non-punitive policies may be more effective at connecting more low-income individuals to child support services without risking compromising health and well-being.

Because of these concerns, the American Public Human Services Association (APHSA) and the National Child Support Enforcement Association (NCSEA), which represent state human services and child support administrators across the political spectrum, opposed a federal mandate that the House of Representatives passed as part of its version of the 2018 farm bill that would require all states to implement cooperation requirements in SNAP.[2] In order to avoid compromising state funds and leaving families more vulnerable for little proven payoff, state policymakers contemplating a cooperation mandate would benefit from considering the many arguments against the policy and the significant downside risks.

This paper provides an overview of the Child Support program, the state options to sanction SNAP participants who do not cooperate with child support, and a discussion of the risks to SNAP participants of such an approach.

More than 1 in 4 children in the United States has a parent living outside their household.[3] Despite separate living arrangements, both parents often can and do contribute to the financial support of their children. Financial support from parents outside the home (non-custodial parents) is particularly important when children live in homes with incomes near or below the poverty line. Of children with a parent living outside their home, 37 percent live in poverty.[4] In these cases, income from a non-custodial parent, when available, can be key to easing financial instability and ensuring that children’s basic needs are met.

One way parents or other guardians can establish shared financial responsibility for a child is to formalize the arrangement through child support services. The Child Support program is a partnership among federal, state, tribal, and local governments that assists parents who live apart to establish binding child support orders that define the scope of the parents’ financial responsibility for their children. Child support orders mandate regular, ongoing payments for the benefit of the child. Payments are typically paid by a non-custodial parent (a parent who does not have physical or legal custody of a child) to a custodial parent (who has primary custody of the child) to support the child’s needs. Unlike other public programs that improve children’s well-being, the Child Support program does not transfer public funds to families but rather enforces the private transfer of income from parents who do not live with their children to the household where the children live, with the aim of enhancing children’s financial security and strengthening the ties between children and non-residential parents.

A typical child support case includes several steps:

- Locating the non-custodial parent, when necessary, using information provided by the parent opening the case;

- Determining parentage (if the couple was not married when the child was born), so that both parents have a legally established relationship with the child;

- Establishing an order, which determines how much the non-custodial parent will pay and what the payment structure will be;

- Enforcing an order by collecting support from non-custodial parents who have lapsed payments, which can include garnishing an indebted parent’s wages;

- Distributing child support; and

- Reviewing child support orders and modifying them when appropriate.

Much like SNAP — which helps feed 17 million low-income children each month[5] — the Child Support program has a wide reach. Over 60 percent of custodial families participate in the Child Support program. The Child Support program serves about 15 million, or 1 in 5, children each year, making it one of the country’s largest income-support programs targeting children.[6] Two-thirds of children under age 18 eligible for child support services participated in the program.[7] Evidence confirms that the Child Support program increases economic stability in custodial households.[8] Research shows that, by establishing enforceable orders, the Child Support program increases the consistency and amount of monetary support that non-custodial parents provide to their children.[9] In fiscal year 2018, child support collections accounted for over $27 billion in direct financial support for households with children.[10]

Child support income is particularly important for low-income households. For custodial families living below the poverty line, it constitutes a substantial share of overall income. According to the most recent Census data, child support payments account for nearly 58 percent of the mean personal income of poor custodial parents who receive full child support payments (meaning the total amount ordered) and 28 percent for poor custodial parents receiving partial payments.[11] For some custodial households, the Child Support program provides a pathway out of poverty. In 2018, child support income lifted nearly 800,000 people, including about 429,000 children, out of poverty.[12]

Furthermore, child support can improve children’s and parents’ overall well-being. Participation in the Child Support program is associated with better educational outcomes for children, reduced likelihood of child maltreatment, increased involvement of non-custodial parents with their children, and higher rates of employment and better-quality jobs among single, custodial mothers.[13]

Child support caseloads have declined from 17.2 million in 1999 to 14.5 million cases in 2016,[14] while program performance and efficiency have climbed to historic highs. The decline in child support participation is in large part due to the parallel contraction of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. TANF requires that custodial households open child support cases and cooperate with the Child Support program in order to receive benefits. As the TANF caseload has shrunk, so has the number of families mandated to receive child support services, which has resulted in an overall decline in Child Support program caseloads.

Participation of custodial households that have never received TANF has risen substantially, however, increasing by about 19 percent between 2003 and 2017.[15] This indicates that changes in the Child Support program over that period have attracted more voluntary cases — those in which parents are not compelled, but rather elect to take advantage of child support services. Despite declining caseloads, the Child Support program serves the vast majority of low-income children who have a non-residential parent. Census data show that in 2015, 82 percent of program-eligible children under age 18 in families with incomes below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) participated. [16]

In tandem with these caseload trends, the Child Support program has enhanced both program effectiveness and efficiency. Though there are fewer open cases in the child support system, the share of open cases with established payment orders has climbed, increasing from 59 percent in 1999 to 87 percent in 2017.[17] Over the same time period, the amount of financial support provided by non-custodial parents to their children has increased, with collections rising by nearly 22 percent in real dollars.[18] And the Child Support program has become more cost-effective, collecting $5.15 for every $1 spent in 2017, versus $3.94 in 1999.[19]

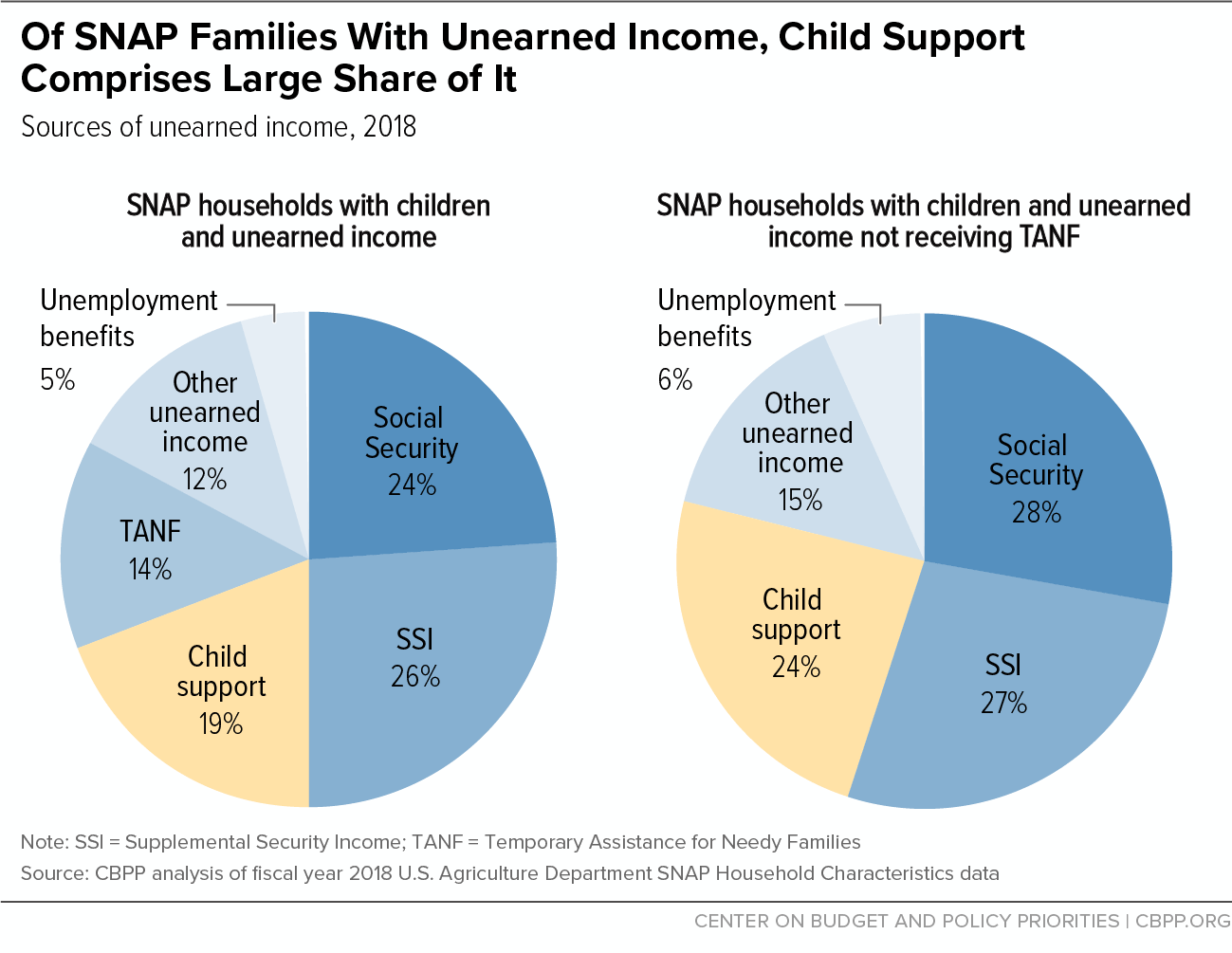

It’s important to understand the already strong overlap between SNAP and formal child support. Nearly one-fifth of all SNAP households with children (including those with parents living together) receive child support payments. The average family on SNAP with child support income receives about $344 per month from a parent not living in the household.[20] For SNAP households with children that have unearned income, child support income makes up about 19 percent of unearned income. Child support payments account for an even larger share in households that do not receive TANF benefits, making up nearly a quarter of unearned income. (See Figure 1.)

Despite the strong overlap between SNAP and the formal Child Support program, many non-custodial parents are providing informal support to their children when they can. They may co-parent and provide for their children consistently and co-equally with the custodial parent outside of a formally ordered agreement. Their support may also be limited by their economic circumstances and take the form of buying needed supplies such as diapers and clothes as well as caring for their children when possible. Similarly, grandparents may be caring for their grandchildren informally when parents are unavailable, perhaps because the parents have jobs or schedules that prevent caring for their children or because they have serious physical or mental health conditions or are participating in substance abuse treatment. These informal arrangements may be working for the families or may be the only circumstances under which caretakers such as grandparents can assume responsibility for the children.

Furthermore, SNAP already includes a strong incentive to encourage low-income non-custodial parents to establish a child support order and make child support payments, which may be one reason few states have adopted a punitive mandate. States can either deduct child support payments from the payor household’s gross income when calculating their household’s SNAP benefits, resulting in a higher benefit level, or can exclude the payments from the payor household’s gross income altogether, which could help a household with child support obligations right around the income cutoff qualify for SNAP. The deduction or exclusion of child support payments increases the SNAP benefits that the payor household can receive, recognizing that resources paid to support a child living in another household are not available to buy food for the non-custodial parent’s household. In 2018, households that claimed the child support deduction received an additional $19.2 million per month than if they’d not claimed the deduction.

These policies acknowledge and reward non-custodial parents who can make their payments by ensuring that SNAP provides more resources to them than to those who fail to meet their obligations. They also create an incentive for low-income non-custodial parents who already provide informal financial support to establish a child support order, so their payments can be appropriately counted to enhance their food assistance.

While most low-income custodial households receive child support services, some do not. And some custodial households that do have child support orders receive incomplete payments or no payments at all from non-custodial parents. These gaps, combined with the downward trend in the child support caseloads, have spurred a public debate about policies that could further improve the program’s reach to low-income families and bolster support payments to vulnerable households. Some argue that the way to accomplish these objectives is to mandate that SNAP applicants cooperate with child support in order to be eligible for food benefits.

In fact, the 1996 welfare law gave states the option to impose such requirements in SNAP, but few currently do. The law includes three options for child support-related SNAP disqualifications, and states may choose to implement any or all.[21] In each case, if the Child Support agency or the SNAP agency determines the parent or caregiver subject to the requirement is out of compliance, they lose SNAP benefits (rather than the entire household).

Disqualifying custodial parents for failure to cooperate. For households with an absent parent, a state may disqualify a custodial parent or other individual with parental responsibility from receiving SNAP benefits if they fail to cooperate with the Child Support program and are unable to demonstrate good cause for failure to cooperate. For individuals subject to the requirement, cooperation includes opening a case against the absent parent and working with the child support agency to determine parentage (if necessary) and establish, modify, or enforce a support order.[22]

TANF and Medicaid mandate that custodial parents cooperate with the Child Support program in order to receive benefits. A SNAP applicant who meets the requirement for TANF or Medicaid is considered to be cooperating for the purposes of SNAP.

Disqualifying non-custodial parents for refusal to cooperate. States can choose to disqualify non-custodial parents from SNAP if they are determined to be refusing to cooperate with the Child Support agency in establishing parentage (if necessary) and/or providing child support. [23]

Disqualifying parents with child support arrears. States have the option to disqualify any individual who has outstanding debt on court-ordered child support payments unless a court has permitted the individual to delay payment or has ordered a payment plan with which the individual is complying.[24]

All of these state options have proven unpopular. According to the Department of Agriculture, only eight states currently implement any of the child support-related disqualifications.[25]

Case for Mandatory Cooperation Is Built on Flawed Presumptions

Proponents believe that child support-related disqualifications in SNAP will compel parents to change their behavior. But this assertion is based on a series of flawed presumptions and a failure to assess the factors that drive non-participation in the Child Support program.

-

Mandatory cooperation may disrupt existing family arrangements. A mandatory cooperation requirement fails to recognize, and may even disrupt, informal child support arrangements. Custodial parents without formal child support arrangements may be different from those with cases. Some custodial parents may decide that the formal child support system does not provide the flexibility that non-custodial parents with unstable, low-wage employment need. Parents may instead work out a child support arrangement that responds to the various pressures facing the parents, such as seasonal employment, family emergencies, or unexpected expenses.

Custodial parents who choose not to pursue a child support case may, for example, be more likely to be completely disconnected from the other parent, may not understand the child support system, or may be frightened to initiate an enforcement action against the other parent. For instance, some survivors of domestic violence decide that seeking child support would threaten their or their children’s safety. Research from Texas found that more than 4 in 10 mothers who do not receive formal or informal child support are survivors of emotional or physical abuse.[26]

Taking away vital food support before understanding these parents’ barriers to participation and assessing non-punitive solutions is premature and introduces enormous risk for low-income families. Instead, the Child Support program could engage these parents and address their particular circumstances. For example, if a custodial parent is hesitant to pursue child support because they are worried it will inflame the relationship with the other parent, their anxieties may be alleviated if they are able to engage with the Child Support agency to better understand the implications of opening a case for both parents. Such engagement would let them voice their concerns, ask questions, and understand their rights and protections without fearing their food assistance would be revoked. Similarly, informal and successful custody arrangements by grandparents could be threatened if parents are angered by a grandparent involving the Child Support program when they tried to add the grandchild to their SNAP case. Custodial parents who are working with non-custodial parents to strengthen informal parenting and support arrangements may find those relationships disrupted if the Child Support program intervenes.

- Non-custodial parents who do not participate in child support or do not make complete payments may face real barriers. A cooperation requirement presumes that non-custodial parents who are not engaged with the Child Support program or are behind on their payments are willfully delinquent. In fact, they may be more likely to face economic struggles that prevent them from complying with an order. Some non-custodial parents face an impossible trade-off between paying child support and slipping deeper into poverty. About a quarter of non-custodial parents live in poverty, and in 2018, 300,000 individuals fell below the poverty line as a result of paying child support obligations.[27] For these individuals, mandating cooperation would not alter their ability to pay. Moreover, non-custodial parents who are unable to pay child support may be more likely to avoid engagement with the Child Support agency for fear of enforcement actions that could result in greater hardship, including incarceration. As with custodial parents, denying low-income non-custodial parents food assistance before identifying and addressing their barriers could result in significant harm.

- The costs associated with mandatory cooperation could dwarf the benefits. Proponents of a cooperation mandate presume that increased child support payments will outweigh the costs associated with implementing such policies, including establishing orders and pursuing collections. But if the underlying assumptions about a punishing policy’s ability to compel behavior change among parents is wrong, this would not bear out.

- States need to explore non-punitive approaches to Child Support services. Advocates for mandatory cooperation presuppose that child support is a program that eligible parents actively avoid, and that only a sanction can compel their participation. In fact, voluntary child support cases have increased over the last 15 years, suggesting that increasing numbers of families recognize the value of the Child Support program’s services.[28] Targeted promotion and marketing of child support services to non-participants could boost engagement among low-income families, without threatening food. Over the past decade, the Health and Human Services Department’s Office of Child Support Enforcement (OCSE) has been funding demonstration projects and studies that test a wide range of innovative approaches, including digital marketing, behavioral interventions, supportive employment services, and other alternatives to traditional, more punitive approaches.[29]

Understanding the implications of child support cooperation requirements in SNAP requires challenging these presumptions, assessing the current linkages between the Child Support program and SNAP, and analyzing the potential harm to vulnerable families, including children.

Child Support is a critical anti-poverty program, and efforts to expand and improve it are laudable. But taking away vital food assistance from low-income families that do not participate or are unable to make child support payments is a dangerous policy that threatens children’s as well as custodial and non-custodial parents’ well-being.

Although states have had the option to tie SNAP eligibility to child support cooperation for over 20 years, almost nothing is known about its effectiveness. An issue brief commissioned by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Planning and Evaluation summarized this by saying, “While there is heightened interest among state and federal policy makers to expand the mandate for child support cooperation requirements, the impact of the cooperation requirements on program operations and staff workload, program participation, child support receipt, and families’ economic well-being remains largely unknown.”[30]

The risks associated with mandatory cooperation are highly asymmetric. There is no evidence that the policy generates significantly more child support payments to custodial households without substantially threatening children’s food security. In fact, some organizations that work closely with clients in states that implement a cooperation requirement in SNAP or other safety net programs have flagged that these mandates have threatened needy families’ access to vital resources.[31] And implementation of a cooperation mandate carries high costs and complexity, which can lead to less efficient child support administration and bureaucratic errors that result in SNAP participants incorrectly having their benefits cut.

Given the lack of evidence about the policy’s costs and effectiveness in states that have implemented it and the administrative burden associated with the policy, APHSA and NCSEA —which respectively, represent state human services and child support administrators across the political spectrum — both opposed a national mandate when House Republicans included it in their version of the 2018 farm bill.[32]

When parents lose food assistance for non-cooperation, both parents and children stand to get hurt. If a custodial parent is subject to a mandate and fails to cooperate, sanctioning their SNAP benefits reduces the family’s overall food budget and puts children at increased risk of food insecurity and inadequate nutrition. Given that custodial families are more likely to be people of color, who already face higher rates of food insecurity, enforcing child support cooperation requirements in SNAP will disproportionately hurt children of color and increase racial inequities.

In 2014, Utah commissioned a study on the impact of such a requirement. The study projected a cooperation mandate would take a significant number of adults off food assistance but few would end up receiving additional funds from child support payments, a dynamic that would leave households with fewer resources and the children in them more vulnerable.[33] Restricting children’s access to sufficient food has short- and long-term impacts. Research indicates that additional food assistance to a household reduces children’s food insecurity and improves the nutritional value of their diets.[34] Consistent access to adequate nutrition in childhood is also associated with important longer-term outcomes, including greater educational achievement and better health.[35]

As described above, custodial parents who choose not to engage with the child support agency often have a good reason. Some already receive support from the other parent and some do not want to risk undermining the relationship with the other parent to pursue support if they know that parent cannot provide more. Others have suffered abuse and fear that engagement with the Child Support agency will put them at risk. In fact, survivors of domestic violence may qualify for a good cause exemption from a cooperation mandate — but they may not know to pursue one. And SNAP eligibility workers often lack the training to screen for domestic violence and are not qualified to make appropriate determinations about whether it is safe for someone to engage child support officials. Taking away SNAP from parents who decide that it isn’t in their family’s best interest to pursue child support will leave them with less help affording food.

Moreover, a custodial parent who has reason to fear for their safety or that of their children, faced with a cooperation requirement, may be too scared to apply for benefits at all, which means the household would forgo SNAP assistance entirely. Many people apply for SNAP online or through a written application without assistance. Sometimes information on the SNAP application about the cooperation requirement and related exemptions is not clear or is scant. In such cases, a custodial parent may be hesitant to submit a SNAP application if they believe their information will be automatically handed over to the Child Support agency or if they are unsure if SNAP would exempt them from the requirement.

A cooperation mandate on custodians also puts food assistance at risk for low-income households in which a grandparent, or other relative caregiver, has taken on parental responsibilities. More than 2.5 million grandparents are raising their grandchildren.[36] Many are doing so informally, without official custody or foster care arrangements. A requirement for custodians to pursue child support would mandate that these grandparents seek payments from parents in order to be eligible for SNAP benefits. Some grandparents might forgo SNAP if they had concerns about the state pursuing the parents for child support. For example, a grandparent might not want to implicate a parent struggling with drug addiction or mental health issues in a child support enforcement action. Also, in cases involving prior abuse by a parent, the grandparent might fear for their own safety or the child’s if they sought child support. And if a grandparent did seek child support, the parent might reclaim custody of the child — which might not be in the child’s best interest — rather than pay support.

Similarly, taking away SNAP benefits from a non-custodial parent who is struggling to meet their own basic needs for non-cooperation with the Child Support program can hurt both the parent and their children. It makes them even less capable of providing financial support to their children, no matter how much they may want to meet their obligations, and serves to perpetuate instability. Moreover, even when non-custodial parents cannot pay the full amount of their orders, many provide partial payments or in-kind support (e.g. meals, child care, or diapers). Taking away their food assistance because they are deemed not to be cooperating or because they are behind on their payments will restrain their ability to provide any support, ultimately threatening their children’s well-being. Furthermore, some non-custodial parents live in households with other minor children. When their benefits are cut, they have fewer resources to feed the children with whom they reside. For those bad actors who have sufficient resources to provide regular payments but refuse to do so, states have more direct enforcement levers than restricting food, including garnishment of wages or seizure of assets.

Though important to address, the gap in eligible, low-income families unserved by child support is relatively modest. Census data show that 72 percent of custodial families with incomes below 200 percent of FPL and nearly 80 percent of custodial families below 100 percent of FPL are already engaged with the Child Support agency to pursue payments they are due.[37] When Utah assessed the costs and benefits of implementing mandatory cooperation, the state similarly found that nearly 70 percent of custodial parents receiving SNAP already had an open child support case.[38]

Further, some custodial parents without child support orders receive support from non-custodial parents through other formal arrangements. For example, many families that do not have child support orders may have private, court-ordered agreements (such as divorce agreements) to share financial responsibility for their children. A cooperation mandate would make parents without an open child support case ineligible for SNAP even if they have another formal arrangement in place. Forcing them to open new child support cases would unnecessarily burden parents and caseworkers and waste taxpayer resources.

Still other custodial parents without formal child support cases receive support from non-custodial parents through informal arrangements. Studies have found that low-income, non-custodial parents provide significant support for their children through informal means, which includes providing cash directly to the custodial parent or in-kind contributions (such as clothing, school supplies, or food) outside of the child support system.[39] Low-income families may prefer informal support arrangements for a variety of reasons, including a desire to avoid government involvement in private affairs or to encourage involvement of the non-custodial parent in child rearing (because informal and in-kind support more likely involve the non-custodial parent visiting the custodial parent and seeing the child).

Even if cooperation requirements increased the number of open child support cases for those not currently participating, it likely would not substantially increase the resources available to children, since low-income, non-custodial parents often face significant financial hardship and can make only limited payments, if any. Lack of regular, reliable income or accrued debt can make it hard for many poor non-custodial parents to pay child support regularly. Low-income, non-custodial parents have limited resources. Studies have found that, among low-income families, increasing formal child support payments through enforcement may reduce informal and in-kind contributions, leaving children and custodial parents no better off in terms of overall resources.[40]

Since mandatory cooperation does nothing to improve their economic stability, non-custodial parents in this situation may be reluctant to engage with the Child Support agency. Many custodial parents who do not seek formal child support orders opt out because they believe the non-custodial parent could not afford to pay or already provide what they can.[41] Job instability may make it difficult for non-custodial parents to consistently meet formal child support obligations and custodial parents may prefer informal support arrangements which allow non-custodial parents to support their children when they are able to do so. In these cases, mandatory cooperation would make neither the custodial nor the non-custodial parent better able to support their child.

Similarly, taking benefits from struggling non-custodial parents with existing orders who owe arrears will make them worse off without improving their ability to meet their obligations. Research indicates that the vast majority of parents who are unable to pay and fall behind on their child support payments have unstable employment and low earnings.[42] It is common practice in state and county jurisdictions to impute or assume full-time minimum-wage earnings when determining low-income, non-custodial parents’ child support obligations, even if they are unemployed, work part time, or have unstable work.[43] This sets child support orders unrealistically high relative to the actual earnings of low-income parents and leads to the accumulation of child support debt. Evidence suggests that about 70 percent of child support debt is held by those with incomes of $10,000 a year or less.[44]

Costly, Administratively Burdensome, and Likely to Degrade Child Support Program Efficiency

Mandating that custodial and non-custodial parents cooperate with the Child Support program is administratively complex and carries significant costs for the government, and by extension, taxpayers. Since the late 1990s, the Child Support program has made considerable progress across the country in collecting more from non-custodial parents, both overall and per dollar spent to run the program.[45] Cooperation requirements threaten that progress and can cost more than they yield for low-income children.

They require expensive investments in systems change, considerable enhancements in information sharing between state SNAP workers and Child Support staff, and appropriate and timely notification of SNAP applicants and participants. Furthermore, such mandates result in many new cases that require additional Child Support staff and drain resources from existing cases, yet yield little or no additional child support payments. The study Utah commissioned to explore mandatory cooperation found that implementation would cost between $3.2 million and $3.6 million for systems changes and new Child Support staff, without a significant boost in collections.[46] When the Congressional Budget Office estimated the cost of implementing the policy nationally, it similarly projected that associated administrative costs borne by the federal and state governments would far exceed new child support payments.[47]

Moreover, non-voluntary cases often require more Child Support program resources. For example, if a custodial parent is obligated to open a new case under the requirement and isn’t in contact with the non-custodial parent, the Child Support agency may have to spend considerable time and money tracking down the non-custodial parent and establishing parentage before beginning the process to put a child support order in place. And, as discussed, custodial parents often don’t pursue child support when they know the non-custodial parent can afford to pay little — so even if Child Support tracks down the non-custodial parent, establishes parentage, and puts an order in place, the payoff may be very low.

Finally, cooperation requirements necessitate careful coordination and communication between the Child Support program and SNAP agencies to determine, on a regular basis, if parents subject to the policy are in compliance. This involves complex administrative challenges that can result in individuals who have met their obligations being denied food assistance because of bureaucratic errors.

It’s important to reach more low-income families that could benefit from child support and to increase payments to eligible custodial households. But putting families’ food at risk and threatening children’s well-being through mandatory cooperation policies that aren’t likely to result in more financial support for children is not the right approach. In recent years, the Child Support program has moved toward a family-centered approach that aims to work with both parents, address families’ specific needs, and mitigate barriers to payment, in part, by distinguishing between non-custodial parents who are unwilling to pay versus those who are unable to.[48] A blunt, punitive instrument like the SNAP disqualifications some are proposing runs counter to this approach and prematurely disregards other options.

Instead, policymakers and program administrators need to assess the reasons parents do not or cannot engage with the Child Support program and design solutions that lower the barriers to facilitate their participation and drive higher collections. The solutions may require policy or programmatic changes within the Child Support program itself, rather than punitive policies in SNAP. Some approaches the Child Support program can explore include deeper assessment of non-participation, enhanced marketing efforts, streamlined referrals between SNAP and Child Support, and expanded supportive services and referrals.

- Assessment of non-participation. The national-level data and accounts from front-line staff and client-facing organizations give us a good sense of why some parents, both custodial and non-custodial, choose not to engage with the Child Support program. Before designing policies to increase participation and child support payments, state and local SNAP and Child Support agencies need to conduct a thorough analysis of cross-program participation and the barriers preventing parents in their jurisdiction from participating. Non-participating families may require different types of recruitment and engagement.

-

Enhanced marketing efforts and streamlined referrals. Targeted promotion of child support services to non-participants and streamlining the referral process between SNAP and Child Support could boost engagement among low-income families, without threatening food access. Custodial parents may be more likely to engage with the Child Support program if they better understand the implications for themselves, the other parent, and their children. For example, a custodial parent concerned about the other parent’s ability to pay may be willing to open a case if they believe an order amount will be determined based on the non-custodial parent’s ability to contribute financially and won’t create undue hardship. A non-custodial parent, on the other hand, could be persuaded to cooperate if they understand the value of formalizing financial payments to create a legal record of their ongoing support for their child.

With funding from OCSE, states are testing a range of approaches to increase awareness and interest in the program among non-participating families, including targeted digital advertising through social media, live chats between agencies and potential participants, online applications, and outreach campaigns to targeted audiences (such as Spanish-speaking populations and families in rural areas). States could test strategies to strengthen the referral process from SNAP to child support services — Child Support staff could be co-located with SNAP eligibility workers so that they can handle questions about the Child Support program, explain its benefits, and even open a case if the family is interested. Or SNAP staff could be trained to speak with SNAP participants about the Child Support program and refer them directly to Child Support staff.

-

Expanded supportive services. When non-custodial parents struggle to meet their own basic needs, it is important to increase their financial stability so they can support themselves and their children. As discussed, policies that take away fundamental support — like a sanction of their SNAP benefits — will only further destabilize them. Traditional child support enforcement methods rely on punitive sanctions to address noncompliance, including suspending driver’s licenses or passports, seizing assets, and incarceration. With support from OCSE and in partnership with other agencies, state child support enforcement agencies have been experimenting with alternative approaches that focus on supportive, family-oriented methods.

States have been testing enhanced and expedited review of child support orders, modifying a parent’s child support order if the payment structure is infeasible given their financial circumstances, and offering debt-reduction planning or tying reduction of arrears to successful participation in a parenting program. Rather than punishing non-custodial parents struggling to make regular payments, some states offer supportive programs that address barriers to employment. These programs offer a range of services, including case management, employment services, coaching and mentoring, parenting classes, domestic violence services, mediators to help arrange parenting time, and subsidies for transportation and work equipment.

In lieu of adopting policies that punish parents for shying away from the Child Support program, states need to better understand the barriers parents face and the changes Child Support can make to address them. Policymakers and program administrators can most effectively improve low-income children’s circumstances by designing policies that respond to families’ needs.

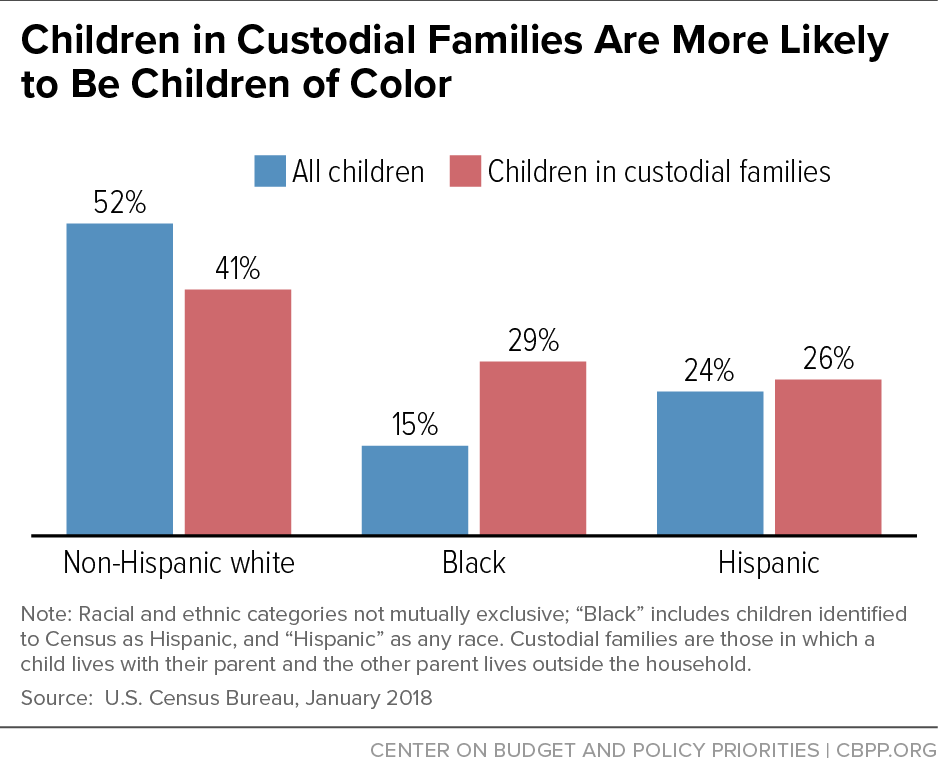

Custodial families and their children are demographically diverse and do not fit in a particular type. More than 1 in 4 U.S. children (under the age of 21) has a parent living outside their household.[49] Children living in custodial families are racially and ethnically diverse but are disproportionately likely to be children of color: 41 percent of children in custodial families are non-Hispanic white, 29 percent are Black, and 26 percent are Hispanic, compared to 52 percent, 15 percent, and 24 percent, respectively, of all U.S. children.[50] (See Appendix Figure 1.)

While most custodial families are headed by mothers, an increasing proportion are headed by fathers. In 2016, fathers headed 20 percent of custodial families, up from 16 percent in 1994.[51] The average age of custodial parents was 38 years and a majority (55 percent) of them had only one child eligible for child support services.[52] Nearly half (46 percent) of custodial parents have a high school degree or less. About 7 in 10 custodial parents who were supposed to receive child support in 2015 received some payments, while 6 in 10 custodial parents received some type of non-cash support from the non-custodial parent.[53]

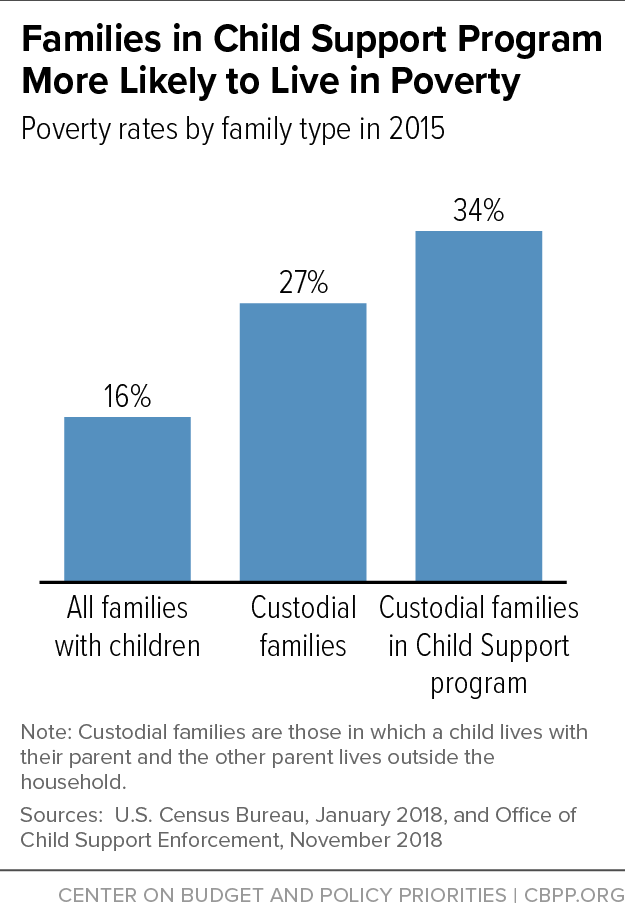

Custodial families have relatively low incomes and are more likely to live in poverty. While 16 percent of families with children under 18 lived in poverty in 2015, about 27 percent of custodial families were poor.[54] Custodial families participating in the Child Support program are even more likely to be low-income, with a poverty rate of 34 percent.[55] (See Appendix Figure 2.) Custodial parents participating in the Child Support program were less likely to have education beyond a high school degree (49 percent) than those not participating in the program (63 percent). Custodial parents in the Child Support program were also less likely to have a year-round full-time job (44 percent) than those not participating in the program (69 percent). [56]