- Home

- Federal Tax

- 2017 Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed

2017 Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed

The major tax legislation enacted in December 2017 will cost about $1.9 trillion over ten years and deliver windfall gains to wealthy households and profitable corporations, further widening the gap between those at the top of the income ladder and the rest of the nation.[1] By shrinking revenues, it will leave the nation less prepared to address the retirement of the baby-boom generation and other national needs that will require more revenue. Moreover, the complex, hastily drafted legislation will likely trigger a surge in tax gaming that could pose a risk to the integrity of the U.S. tax system.

Policymakers should set a new course and pursue tax reforms that avoid the regressivity of the 2017 tax law and accord more favorable treatment to working people with low or modest incomes, raise revenue to meet national needs, and improve economic efficiency and strengthen the integrity of the tax code.

The 2017 tax law suffers from three fundamental flaws:

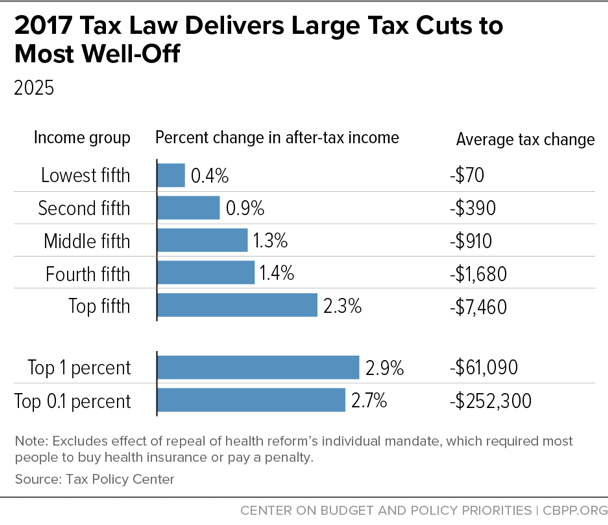

Ignores Stagnation of Working-Class Wages and Exacerbates Inequality

Income has shifted dramatically in recent decades, as wages have been close to stagnant for many working families while rising sharply at the top. As a recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis shows, the share of household income flowing to the bottom 60 percent fell by 4.4 percentage points between 1979 and 2014, while the share flowing to the top 1 percent rose by 5.7 percentage points.[2] Instead of pushing back against this trend, the 2017 tax law exacerbates it. In 2025, when the new law will be fully phased in and before many provisions in it are scheduled to expire, it will boost the after-tax incomes of households in the top 1 percent by 2.9 percent, roughly three times the 1.0 percent gain for households in the bottom 60 percent. The tax cuts that year will average $61,090 for the top 1 percent — and $252,300 for the top one-tenth of 1 percent (see graph).

The 2017 tax law’s heavy tilt to the top largely reflects several large provisions that primarily benefit the most well-off. Its core provision is a deep cut in the corporate tax rate, which will mostly benefit shareholders and highly compensated employees such as CEOs. The law also showers large tax benefits on heirs to multi-million-dollar estates, cuts the top income tax rate, weakens the Alternative Minimum Tax, and provides a special deduction for certain business owners who are disproportionately high income.

The economic circumstances of low- and moderate-income working families, in contrast, are largely an afterthought in the 2017 tax law. For example, in last-minute changes to the bill, negotiators agreed to a deeper cut in the top individual tax rate but rejected calls from Senators Marco Rubio and Mike Lee to deliver more than a token increase of $75 or less in the Child Tax Credit to 11 million children in low-income working families. And lawmakers who drafted the law apparently didn’t even consider strengthening the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which is well placed to boost working-family incomes.

The 2017 tax law will also harm many working families. For example, its repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate — the requirement that most people enroll in health insurance coverage or pay a penalty — is expected to add millions to the ranks of the uninsured and increase insurance premiums in the individual market.

Weakens Revenue When Nation Needs to Raise More Revenue

The new tax law will cost $1.9 trillion over ten years (2018-2027), according to CBO estimates. CBO also finds that the law will only modestly improve economic growth — enough to recoup only about one-quarter of these costs. These large revenue losses are irresponsible given the fiscal challenges the nation will face over the next several decades due to an aging population, health care costs that outpace economic growth, the return of interest rates to more normal levels, potential national security threats, and current and emerging domestic challenges (such as large infrastructure needs that cannot be deferred indefinitely).

Because of these pressures, CBPP and other analysts project that spending will need to rise as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Most of the growth will occur in a few programs — Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid — with widespread public support and where growth reflects demographic and health-care cost factors, not more generous coverage or benefits. These pressures will require revenue as a percentage of GDP to be higher than in the past to prevent an unsustainable rise in the nation’s debt ratio in coming decades. The 2017 tax law, however, pushes in the opposite direction.

Invites Tax Gaming and Risks Undermining Integrity of Tax Code

True tax reform simplifies the tax code and narrows the gaps between how different types of income are taxed so that individuals and businesses base their economic decisions on economics, not taxes. The 2017 tax law does the opposite, adding complexity to the tax code and introducing new, arbitrary distinctions between different kinds of income. The law “has turned us into a nation of tax shelter hunters,” the Tax Policy Center’s Howard Gleckman has observed:

- A prime example is the 2017 tax law’s 20 percent deduction for “pass-through” income, or income from businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships that business owners claim on their individual tax returns. The deduction effectively means that certain pass-through income will face a lower tax rate than wages and salaries, creating an incentive for high-income individuals to reclassify their salaries as pass-through income. While the tax law includes complex "guardrails" intended to prevent such abuse, they are poorly designed.

- The 2017 tax law also creates a powerful incentive for wealthy Americans to shelter large amounts of income in corporations by slashing the corporate rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, thereby opening up a wide gap between the top individual tax rate and the corporate rate.

- The 2017 tax law moves U.S. international tax rules to a “territorial” system, largely exempting corporations’ foreign profits from U.S. tax and thereby encouraging multinationals to shift profits and operations overseas. While the law includes a minimum tax aimed at limiting this incentive, it is seriously flawed. In fact, the minimum tax could actually add to incentives to shift both paper profits and real investments and operations overseas.

End Notes

[1] For further information, see Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 14, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-tax-law-is-fundamentally-flawed-and-will-require-basic-restructuring.

[2] The share of income going to the top 1 percent increased from 7.4 to 13.1 percent, while the share going to the bottom 60 percent fell from 36.3 to 31.9 percent. Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2014,” March 19, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53597. Income shares have been recalculated to exclude households with negative income.