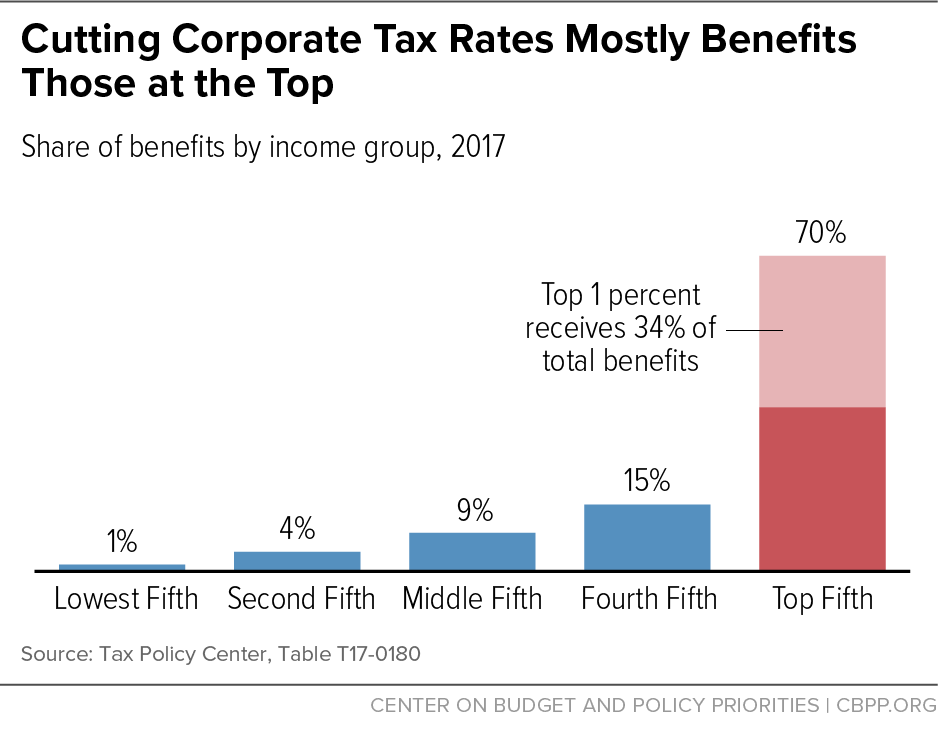

The tax framework that the Trump Administration and congressional Republican leaders announced on September 27 proposes cutting the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has repeatedly argued that the Administration’s “objective” for corporate tax cuts is boosting workers’ wages because “many, many economic studies show that more than 70 percent of the burden of corporate taxes are passed on to the workers.” This claim is misleading, however, and the assertion that most of the benefits would go to workers misses the mark. The evidence indicates that most of the benefits from a corporate rate cut would go to those at the top, with only a small share flowing to low- and moderate-income families. Mainstream estimates conclude that more than one-third of the benefit of corporate rate cuts flows to the top 1 percent of Americans, and 70 percent flows to the top fifth. Corporate rate cuts could even hurt most Americans since they must eventually be paid for with other tax increases or spending cuts.[1]

Mnuchin’s estimate that 70 percent of the corporate tax flows to workers is an outlier from the mainstream consensus and is used only by the Tax Foundation.[2] Most organizations assessing the empirical evidence conclude that the bulk of corporate rate cuts goes to the owners of corporate and other types of capital — not workers.

Congress’s official non-partisan scorekeepers, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), as well as the Tax Policy Center (TPC), Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis, and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy assess the research as showing only a quarter or less of corporate taxes fall on workers; thus, they’d receive a quarter or less of the benefit of corporate tax cuts.

The most prominent empirical estimate that might support Mnuchin’s claim is a series of papers by the American Enterprise Institute’s Kevin Hassett (now chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers) and Aparna Mathur concluding that a 1 percent increase in the corporate tax rate reduces wages by nearly 1 percent.[3] However, other researchers have viewed these results skeptically, and other recent empirical work suggests that at the very most, workers bear 40 percent of corporate taxes.

Mnuchin’s aides have also cited a study by Céline Azémar and Glenn Hubbard to assert that workers pay 60 percent of the corporate tax. Yet, as the Congressional Research Service’s Jane Gravelle points out, this figure largely reflects high union membership rates and would probably be negligible for the United States, given its low union membership rate.[4]

One reason why the 70 percent figure is implausible is that recent research suggests that at least 60 percent of the corporate tax falls on corporate investors because 60 percent of the tax applies to unusual corporate profits (such as from monopoly power) that benefit them alone. That leaves at most 40 percent of the tax that can be borne by workers.

Whatever share of a corporate rate cut eventually flows to workers would likely do so in proportion to their share of total wage and salary income. Labor income is concentrated among high earners such as highly paid executives, lawyers, and other professionals. For example, in 2015, about 48 percent of labor income went to the top 20 percent of the income distribution, and more than 10 percent of labor income went to the top 1 percent, TPC estimates. Thus, only a small benefit would ultimately flow to struggling workers who have been hurt most by slow wage growth in recent decades.

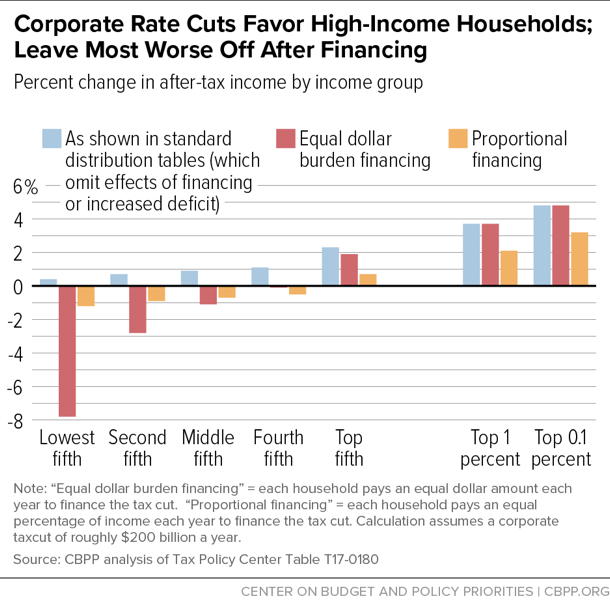

If corporate tax cuts aren’t offset by tax increases or spending cuts, the resulting increased deficits would reduce national saving, meaning less capital would be available for investment in the economy and interest rates would consequently rise. This would ultimately reverse any increase in investment caused by the rate cut, preventing productivity and workers’ wages from rising. For corporate tax cuts to produce sustained wage gains for workers, they must be offset with some combination of tax increases and spending cuts.

The offsets could reduce workers’ incomes by more than their increase in wages. Most workers would likely be worse off on net unless the corporate rate cuts were financed largely or entirely through tax increases on high-income households.

Under reasonable illustrative assumptions about how tax cuts could ultimately be financed, the bottom 80 percent of households would be worse off under the GOP’s corporate rate cut proposal, while the top 1 percent would still get large net tax cuts. (See chart.) If corporate rate cuts were offset — either immediately or in the future — primarily by cuts to programs serving low- and moderate-income people, then the net effects would be even more regressive.

Corporate rate cuts are costly: the GOP proposal to cut the top corporate rate to 20 percent would cost about $2 trillion over ten years, the Tax Policy Center estimates. The idea that this should be a top tax policy priority is based on a series of misleading claims. As other briefs in this series explain, despite claims to the contrary:[5]

- What U.S. corporations actually pay (after tax breaks and loopholes) is in line with other high-income countries.

- U.S. companies are posting record profits, and slashing the corporate rate would not be a good way to address inversions (corporations changing their residence on paper for tax purposes).

Instead of slashing the corporate tax rate, true corporate tax reform that addresses inefficient corporate tax breaks, loopholes, and the tilt of the tax code towards debt and foreign investment would be more likely to foster growth.