- Home

- What To Look For As Congress Begins Work...

What to Look for as Congress Begins Work on 2017 Appropriations

As Congress begins work on 2017 appropriations, it faces tight constraints. Last year’s bipartisan budget agreement significantly raised the overall caps for defense and non-defense appropriations for 2016 but then froze the non-defense cap at that level for 2017. Increases for high-priority items will require offsetting cuts or savings elsewhere.Thus, any increases for high-priority items such as veterans’ medical care will require offsetting cuts or savings elsewhere.

Once the overall totals have been set, the next step is normally for the House and Senate Appropriations Committees to allocate the totals among the 12 subcommittees, each of which handles one of the regular appropriations bills. The Senate Appropriations Committee approved its allocations on April 14 based on the totals set by last year’s agreement and has begun sending appropriations bills to the full Senate for action. To implement the overall non-defense freeze, the Senate allocations provide a $3.4 billion (4.7 percent) increase for veterans’ programs, a few smaller increases, and net cuts of varying sizes for seven of the 11 non-defense bills.

The House Appropriations Committee, however, has skipped the allocation step entirely — at least for the time being — and has begun approving individual appropriations bills without making public its overall plan. This highly unusual action reportedly reflects disagreements among House Republicans over the total for non-defense appropriations, with some insisting on reductions below the level set by last year’s agreement. Appropriations Chairman Hal Rogers indicates that he is proceeding based on the total in the bipartisan budget agreement. But with funding levels being announced bill by bill and no overall plan disclosed, it is impossible to judge whether passage of the initial bills will leave insufficient funding for needs taken up later.

Another area of uncertainty is “overseas contingency operations” (OCO), a funding category originally designed to cover extra costs tied to operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other trouble spots. Policymakers in recent years have used some OCO funds (which fall outside the defense and non-defense caps) to help cover costs not strictly associated with overseas contingency operations, and the House Budget Committee-approved budget resolution calls for using considerably more of these funds to supplement the base defense budget. Doing that, however, would require either raising the OCO total above what was agreed to in the 2015 budget agreement or diverting funds from defense overseas contingency operations needs or from non-defense agencies that also receive OCO funding, such as the State Department.

Freeze for 2017 Follows Several Years of Austerity

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) capped total appropriations each year through 2021 for most defense and non-defense programs. Those caps were lowered through automatic cuts (or “sequestration”) set up by the BCA and triggered beginning in 2013 due to Congress’ failure to enact additional deficit reduction legislation. Since then, however, Congress has twice amended the BCA to provide sequestration relief in certain years by substituting other deficit reduction measures.

The most recent BCA amendments came in last October’s bipartisan agreement, enacted as the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, which raised the caps for both 2016 and 2017. It also provided for further supplementing regular appropriations with OCO funding.

The caps for 2017 set under last year’s agreement freeze non-defense[1] appropriations at the 2016 level of $518.5 billion. The agreement also calls for $14.9 billion in non-defense OCO funding, the same as in 2016. For defense programs, the caps allow a $3 billion increase, from $548.1 billion in 2016 to $551.1 billion in 2017.

The lack of an increase above 2016 in the non-defense cap sometimes creates confusion, because last year’s Bipartisan Budget Act is often described as providing increases of $15 billion each for non-defense and defense appropriations in 2017. Those increases, however, are relative not to 2016 but to what the caps would have been if sequestration had remained fully in place. The pattern of sequestration relief in the Bipartisan Budget Act produces a 2017 total that is almost identical to 2016: the amount of non-defense sequestration relief falls by $10 billion in 2017 but the underlying pre-sequestration cap rises by the same amount, producing a flat total (see Table 1).

| TABLE 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Defense Appropriations, in billions of dollars | ||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Change from 2016 to 2017 |

|

| Budget Control Act caps after sequestration (pre-BBA)* | 492.4 | 493.5 | 503.5 | +10 |

| Cap increase provided by BBA | - | 25.0 | 15.0 | -10 |

| Budget Control Act caps (post-BBA)* | 492.4 | 518.5 | 518.5 | 0 |

| Non-defense OCO* | 9.3 | 14.9 | 14.9 | 0 |

| Caps with OCO | 501.6 | 533.4 | 533.4 | 0 |

* BBA = Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015; OCO = Overseas Contingency Operations.

Note: Details may not add to totals due to rounding.

Source: CBPP analysis of Congressional Budget Office data.

Despite the frozen non-defense total, various needs and priorities will create pressures to increase items within that total, requiring offsetting savings elsewhere. Medical care and other services for veterans are a prime example, as rising health care costs, the needs of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and the aging of the overall veteran population combine to drive up appropriations needs. Both the House and Senate Appropriations Committees have already approved their versions of the 2017 bill funding the Department of Veterans Affairs, providing increases above 2016 for veterans’ programs of $2.1 billion and $3.4 billion, respectively.[2] Thus, to stay within the cap, all other non-defense programs will need to be cut by a total of $2.1 billion in the House and $3.4 billion in the Senate.

Other areas in which Congress may seek increases include rental housing assistance (where rising rents will require additional funding just to keep assisting the same number of people), medical research at the National Institutes of Health, and preparations for the 2020 decennial census. Fitting these and other needs into a flat overall total will be challenging.

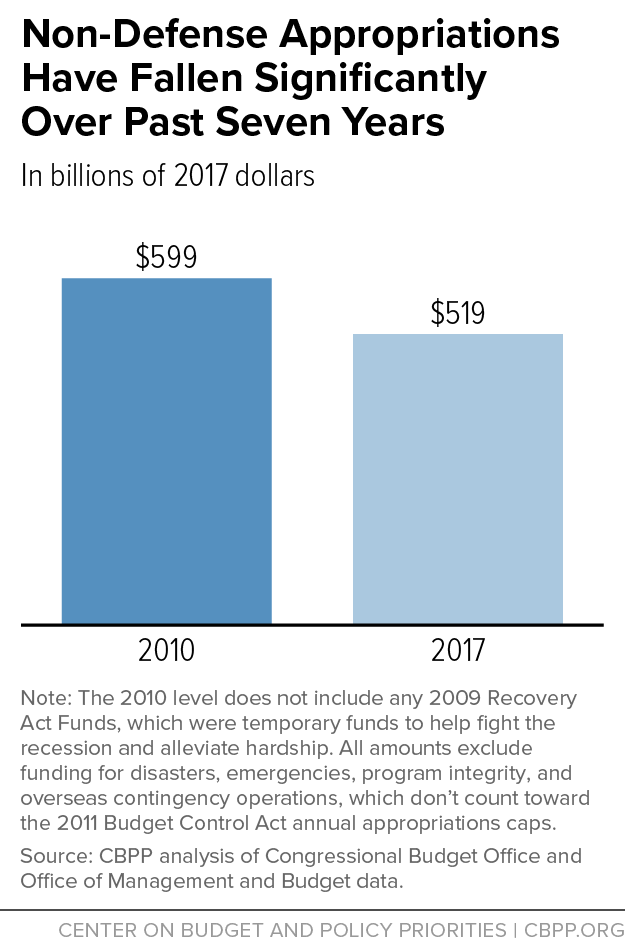

Moreover, the freeze in non-defense funding for 2017 follows several years of austerity produced by the BCA. Even with the sequestration relief in last year’s budget agreement, overall appropriations have fallen substantially over the past seven years. The non-defense cap for 2017 is 13.4 percent below the comparable funding enacted for 2010, after adjusting for inflation (see Figure 1). Even with non-defense OCO funding added, the inflation-adjusted cut over this period is still 11.5 percent.

The effects are even more dramatic when measuring spending relative to the size of the economy. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that non-defense appropriations will equal 3.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017 — just 0.1 percentage points above the lowest level on record in data going back to 1962. Under the current caps, this percentage will set a new record low in 2018 and continue falling thereafter, CBO projects.

Subcommittee Allocations Will Be Critical

Perhaps the single most important decision by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees each year is how to allocate funding among their 12 subcommittees, each of which handles one of the 12 regular annual appropriations bills. These allocations (known as the “302(b) allocations” after the relevant section of the Congressional Budget Act) determine each subcommittee’s total funding for the agencies and programs it handles. They guide the development of the appropriations bills and limit House and Senate amendments on appropriations legislation, since the Congressional Budget Act prohibits amendments that would cause a bill’s allocation to be exceeded.

Under the Congressional Budget Act, the total amount to be allocated among the annual appropriations bills is supposed to be determined through a congressional budget resolution passed by the House and Senate each year.[3] In years when action on the budget resolution has stalled, however, the House and Senate usually adopt other mechanisms to set appropriations totals. (In the House, these mechanisms are generally called “deeming” resolutions, because they deem some amount to be the agreed-on total.)

Last year’s Bipartisan Budget Act included a mechanism for using its totals as the starting point for Senate appropriations action this year. Accordingly, the Senate has allowed its appropriations committee to proceed with subcommittee allocations and begin work on 2017 appropriations bills.

The same mechanism does not apply in the House, however. Nor has the House been able to pass a “deeming” resolution, reportedly because of disagreements among Republicans about whether to set a lower appropriations total than agreed to in the Bipartisan Budget Act. Nevertheless, Chairman Rogers has indicated that the committee is developing appropriations bills based on the Bipartisan Budget Act totals.

Last year, when the bipartisan budget agreement allowed a significant overall funding increase, appropriators gave relatively low priority to the bills funding the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services (HHS), and Education and the Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development (HUD). [4] These two bills together provide more than four-fifths of appropriations for programs assisting households with low or modest incomes. If appropriators place a similarly low priority on these programs again this year, when there is no overall funding increase, some of these programs could face significant funding shortfalls.

Senate Has Allocated Cuts to Most Subcommittees

On April 14 the Senate Appropriations Committee approved its initial set of subcommittee allocations (see Table 2), which demonstrate the effects of the overall freeze on non-defense appropriations. As noted, they provide for a $3.4 billion (4.7 percent) increase for the Department of Veterans Affairs and related programs. The only other increase of significant size is $547 million (1.1 percent) for the Commerce-Justice-Science appropriations bill.

| TABLE 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Defense Allocations to Senate Appropriations Subcommittees, in billions of dollars | ||||

| FY 2016 Enacted | FY 2017 Senate Allocations | Change from 2016 to 2017 | ||

| Dollar | Percent | |||

| Agriculture, FDA* | 21.500 | 21.250 | -0.250 | -1.2% |

| Commerce, Justice, Science | 50.621 | 51.168 | +0.547 | +1.1% |

| Defense | 0.136 | 0.137 | +0.001 | +0.7% |

| Energy & Water | 18.325 | 17.514 | -0.811 | -4.4% |

| Financial Services & General Government | 23.441 | 22.360 | -1.081 | -4.6% |

| Homeland Security | 39.250 | 39.324 | +0.074 | +0.2% |

| Interior & Environment | 32.159 | 32.034 | -0.125 | -0.4% |

| Labor, HHS,** Education | 162.127 | 161.857 | -0.270 | -0.2% |

| Legislative Branch | 4.363 | 4.399 | +0.036 | +0.8% |

| Veterans Affairs | 71.698 | 75.100 | +3.402 | +4.7% |

| State, Foreign Operations | 37.780 | 37.189 | -0.591 | -1.6% |

| Transportation, HUD** | 57.091 | 56.199 | -0.892 | -1.6% |

| TOTAL | 518.491 | 518.531 | 0.040 | 0.0% |

* For comparability, FY 2016 amounts show funding for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in the Financial Services subcommittee, which is where it will be funded in the FY 2017 Senate bills.

** HHS stands for Health and Human Services; HUD for Housing and Urban Development. Source: Congressional Budget Office and Senate Appropriations Committee.

To offset these and two other smaller increases, the Senate allocations assign decreases to seven of the 11 non-defense appropriations bills. They include reductions in non-defense funding of $1.1 billion (4.6 percent) for Financial Services and General Government, $811 million (4.4 percent) for Energy and Water Development, $892 million (1.6 percent) for Transportation-HUD, $591 million (1.6 percent) for the State Department and Foreign Operations, and $270 million (0.2 percent) for Labor-HHS-Education.

For some of the bills, appropriators may be able to use rescissions or other offsetting savings to absorb part of the decreases, thereby reducing the cuts to program funding. For example, in the Transportation-HUD bill, increased receipts from federal mortgage insurance programs will likely cover more than half of the overall reduction specified in the Senate allocations.

House Has Put Off Announcing Allocations

In contrast to the Senate, the House Appropriations Committee has begun considering and approving 2017 appropriations bills without adopting or even making public a set of subcommittee allocations to guide that work.

So far, the full House Appropriations Committee has approved three appropriations bills and a subcommittee has approved a fourth, but with no indication of how these bills fit into the overall total. It is impossible to evaluate the funding levels for individual bills without seeing how they will affect the remaining bills. As Rep. Nita Lowey, the senior Democrat on the committee observed, “Without the full set of subcommittee allocations, it seems to me there’s no way to judge whether the first appropriations bills are allocated more or less than their fair share. We are missing vital information.”

Of the first three bills approved by the House Appropriations Committee, two provide increases in non-defense programs — $2.1 billion (2.9 percent) in the Veterans Affairs bill and $75 million (0.4 percent) in the Energy and Water Development bill — while the third, Agriculture, provides a $451 million (2.1 percent) decrease. The Legislative Branch bill approved in subcommittee also has a small net increase. Thus, the seven non-defense bills that the House committee has not yet addressed will need to produce an overall decrease.

Treatment of Overseas Contingency Operations Also Important

Last year’s Bipartisan Budget Act also specified levels of OCO appropriations for defense and non-defense purposes for 2016 and 2017. [5] How this funding will be used is another aspect of 2017 appropriations that bears watching.

The 2017 budget resolution approved by the House Budget Committee (but not yet taken up by the House) calls for further expanding the role of OCO funds in supplementing regular appropriations for the Department of Defense, specifically recommending that $23 billion of OCO appropriations be used for core defense purposes. In contrast, the President’s 2017 budget indicates that, at the funding levels set out in the Bipartisan Budget Act, only about $5 billion of OCO funds would be available for that purpose. Thus, implementing the House Budget Committee recommendation would require raising the OCO total, changing the division between defense and non-defense uses of OCO funds, or underfunding what the Defense Department says it needs for actual overseas contingency operations.[6]

The Senate Appropriations Committee has announced that it will stick to the OCO total and the division between defense and non-defense uses laid out in the Bipartisan Budget Act. The House Appropriations Committee has not stated a position on the matter. Action on the 2017 Defense appropriations bills may provide the first indication of whether the House or Senate majorities intend to go forward with a plan for expanding the use of OCO to supplement ongoing defense funding, and if so, whether they will accomplish this by reducing OCO funding for non-defense programs and thereby squeezing those programs further.

End Notes

[1] The “non-defense” budget category includes a wide range of programs, including law enforcement and courts, education, national parks, environmental protection, scientific research, and public health, to give just some examples. It also encompasses a number of items often thought of as related to defense and national security, including medical care and other services for veterans, most activities of the Department of Homeland Security, and the budget of the State Department and other foreign assistance programs.

[2] Most funding for veterans’ medical care is provided one year in advance. The figures given here include the advance appropriations for 2017 made in last year’s appropriations bill.

[3] Since enactment of the Budget Control Act in 2011, the overall caps set by that law also limit congressional appropriations action.

[4] David Reich and Douglas Rice, “2016 Appropriations Placed Low Priority on Low-Income Programs; Better Priorities Needed for 2017,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 27, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/2016-appropriations-placed-low-priority-on-low-income-programs-better. The Labor-HHS-Education and Transportation-HUD bills ranked eighth and ninth among the 11 non-defense bills in terms of percentage increases in 2016. Low-income programs overall received less than half the average increase for other non-defense funding.

[5] Non-defense OCO appropriations go to the State Department and related agencies for purposes such as embassy security, international peacekeeping, and economic and military assistance.

[6] David Reich, “House Budget Uses Gimmick for More Defense Funding,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 18, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-budget-uses-gimmick-for-more-defense-funding.

More from the Authors