- Home

- House Appropriations Bills Fall Far Shor...

House Appropriations Bills Fall Far Short of Meeting National Needs

House Republicans are proceeding with a plan for 2018 appropriations that combines massive increases in defense funding with further cuts to non-defense programs.

In particular, the House Appropriations Committee has approved 2018 funding measures that would increase regular appropriations for defense by a total of $70 billion above 2017 while cutting regular appropriations for non-defense programs by $8 billion below 2017. The House Budget Committee has also adopted a budget resolution that incorporates those increases and cuts. And this week the Republican leadership is bringing up for consideration by the full House a package containing some of those appropriations bills — including all of the $70 billion defense increase but only a small part of the non-defense funding cuts.

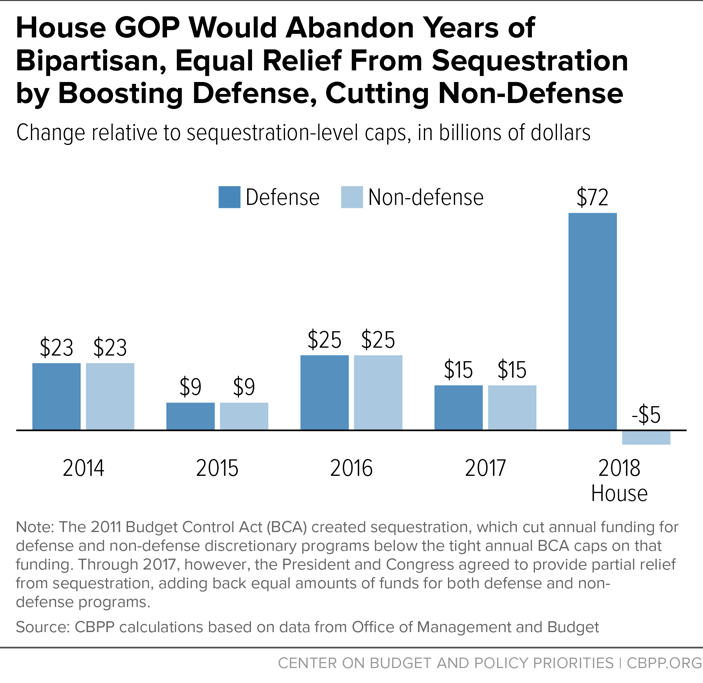

These House appropriations bills are a sharp break with recent practice.These House appropriations bills are a sharp break with recent practice. Since the Budget Control Act (BCA) was enacted in 2011, its caps on overall defense and non-defense funding — as further reduced by the process known as “sequestration” — have tightly constrained both categories. During that period, Congress and the President came together three times to enact legislation scaling back the sequestration cuts for one or two years at a time, with the most recent package covering 2016 and 2017. In each case, the measures provided equal relief for both defense and non-defense programs, recognizing that sequestration made it impossible to meet national needs in either category.

This year, however, the House appropriations bills greatly exceed what the BCA permits — but only on the defense side of the budget. In contrast, for the first time since the BCA was enacted, House appropriations would hold non-defense funding below the level set by the BCA caps and sequestration. The effect of the overall $8 billion cut would be magnified because of the need to provide increases in some non-defense areas, such as veterans’ medical care. Further, the new non-defense cuts would not be one-time events, but rather would follow seven previous years of austerity under the BCA. The proposed House appropriations level would be 17 percent below the comparable 2010 level after adjustment for inflation and 22 percent below 2010 if also adjusted for population growth.

This paper provides examples of the effects of holding non-defense appropriations to the levels House Republicans have proposed, drawn from the 2018 funding bills that the House Appropriations Committee has approved. These examples include:

- Elementary and secondary education. Support for local schools would continue to erode under the House bills, which would cut overall appropriations for elementary and secondary education assistance $2.3 billion below 2017[1] and bring the cumulative inflation-adjusted reduction since 2010 to 20 percent. This year’s proposed cuts include elimination of grants that aid in recruiting, training, supporting, and retaining high-quality teachers and grants for comprehensive family literacy programs.

- Water infrastructure. The House bills would further diminish aid to localities in meeting the cost of upgrading and replacing aging drinking water and wastewater treatment infrastructure. Proposed cuts include a $270 million reduction below 2017 in funding through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which would bring the cumulative reduction to 46 percent below the 2001 level on an inflation-adjusted basis. In addition, Agriculture Department programs geared to the specific needs of rural communities would be cut by $98 million or 17 percent below 2017.

- Job training and employment. Disinvestment in job training and employment programs would also continue. The three core formula grants to states and localities would be cut $86 million below 2017, bringing their inflation-adjusted funding 23 percent below 2010 and 43 percent below 2001, and grants to expand apprenticeship programs would be eliminated. The House bills also eliminate grants to states for operation of the Employment Service, a central component of the workforce system. The Employment Service helps match job seekers to jobs and provides career services in conjunction with, and often before, other related programs.

- Mental health. The Community Mental Health Services Block grant would be cut by one-quarter, from $563 million in 2017 to $421 million in 2018. This block grant helps support essential mental health treatment and related services for people without health insurance, as well as filling in gaps not covered by sources such as private coverage and Medicaid. It is an important element in addressing the opioid crisis, given the frequent link between substance use disorders and mental illness.

- Rental assistance. The House appropriations would defund about 140,000 housing assistance vouchers, as the modest funding increase they provide falls short of what’s needed to keep up with rising rental costs in the private market. Vouchers play a critical role in reducing homelessness, providing stable housing to low-wage working families, and helping seniors and people with disabilities afford homes that meet their needs, but this assistance currently reaches only about 1 in 4 eligible households.

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS budget would be cut by another $149 million below 2017, leaving it $2.9 billion or 21 percent below its 2010 level after adjustment for inflation. Funding pressure since 2010 has forced the agency to sharply reduce its workforce and delay long-overdue upgrades to information technology systems, harming customer service, compromising cybersecurity, and undermining efforts to combat tax avoidance and identity theft.

- Family planning. The “Title X” Family Planning program would be eliminated. This program, which began in 1970, makes grants to state and local health departments and non-profit organizations to provide voluntary family planning services to low-income people, along with related services such as pregnancy testing and counseling and screenings for cancer and sexually transmitted diseases.

- Child care. Appropriations for child care assistance, which helps low-income families afford safe child care while the parents are at work, would increase by just 0.1 percent ($4 million) as compared to 2017 — considerably less than needed to keep up with rising child care costs, let alone make the improvements in quality and safety mandated by bipartisan legislation enacted in 2014. This and related child care programs currently serve considerably fewer children than in 2006 and fewer than 1 in 6 of those eligible.

- Disease control and prevention. The House bills would cut appropriations for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by $198 million, including reductions in areas such as immunization, control of emerging infectious diseases, and tobacco use reduction. The cumulative reduction in CDC’s budget since 2010, adjusted for inflation, would be 12.5 percent.

- Decennial census. Preparations for the 2020 decennial census would be hampered by proposed funding that is well below what is needed two years before the census must be taken. At this point in the census cycle, appropriations are normally ramping up substantially, to address needs like conducting the dress rehearsal, developing a comprehensive advertising and outreach program, and opening temporary offices to help with the logistics of running the census. In the last decade, 2008 funding for the Census Bureau was 79 percent higher than two years earlier, but under the House bill 2018 funding would be only 10 percent above 2016.

- Renewable energy. Energy Department funding for renewable energy research, development, demonstration, and deployment would be cut by almost half, from $2.1 billion in 2017 to $1.1 billion in 2018.

- Repair of federal buildings. Funding for repair of federal buildings and courthouses would be cut from $676 million in 2017 to $180 million in 2018 and funding for construction would be eliminated in 2018, even though federal agencies make rental payments into a fund that is supposed to be used for those purposes and the backlog of needed repairs is estimated to total $1.2 billion.

In sum, the House is on a path toward producing appropriations legislation that falls short of meeting important national needs. A far better approach would be the one that has been used three previous times this decade: equal sequestration relief for both the defense and non-defense categories, thereby allowing more adequate appropriations on both sides of the budget.

The House Majority’s Basic Plan: Massive Defense Increases and More Non-Defense Cuts

The House Appropriations Committee has produced funding bills for 2018 that depart radically from the current caps and from the past practices in adjusting those caps. Defense funding in those bills totals $621.5 billion, which is $72 billion above the 2018 BCA cap and $70 billion above 2017. That level not only assumes elimination of all sequestration cuts in defense in 2018, but adds an additional $18.5 billion above the original pre-sequestration defense cap. In contrast, on the non-defense side the House bills assume no sequestration relief, but rather set funding $5 billion below the full sequestration level and almost $8 billion below 2017. (See Figure 1.)

The defense funding levels in the bills written by the House Appropriations Committee are merely hypothetical, however, unless agreement is reached on legislation to amend the BCA, since they violate the BCA cap on defense appropriations. Because of the enforcement mechanism written into the BCA, if those bills were enacted without the BCA having been amended, they would trigger large across-the-board cuts in defense funding to bring the total down to the cap level. Thus, negotiations are needed regarding realistic adjustments to the BCA caps that would allow funding sufficient to meet important needs on both the defense and non-defense sides of the budget.

Non-Defense Priorities in the House Bills

As noted, under the framework adopted by the House Appropriations and Budget committees non-defense appropriations for 2018 total almost $8 billion less than in 2017 — a cut $5 billion larger than the BCA requires, even with sequestration fully in place.

Within that decreased total, the House Appropriations Committee provided substantial increases for two of the 11 appropriations bills[2] that carry non-defense funding, a small increase for a third, and substantial cuts for the other eight. Table 1 shows the non-defense increases and cuts in each of the bills for 2018.

As might be expected, the largest funding boost comes in the veterans’ portion of the Military Construction and Veterans Affairs bill, which would receive an increase of $3.9 billion or 5.3 percent above 2017. Veterans’ programs are counted on the non-defense side of the budget and currently represent about one-seventh of the non-defense appropriations total. Essentially all of the increase is for veterans’ medical care, where rising funding needs reflect demographic factors, the needs of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and health care cost increases. There is widespread support for meeting veterans’ health needs, and it seems likely that whatever appropriations are eventually enacted for 2018 will include an increase similar to the House bill.

The second-largest increase proposed by the House Appropriations Committee is $1.9 billion (4.7 percent) for the Homeland Security appropriations bill. The committee directed all of that increase to the two main border security and immigration enforcement agencies:

- Customs and Border Protection (CBP) funding would rise by $1.6 billion (13 percent), to support constructing fences and other barriers along the southern border, hiring 500 additional Border Patrol agents, and acquiring additional aircraft, technology, and equipment; and

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would rise by $620 million (10 percent), for hiring an additional 1,000 agents and expanding detention capacity, among other uses.

These 2018 increases would come on top of substantial increases enacted for 2017, bringing the cumulative two-year increase between 2016 and 2018 (before adjustment for inflation) to 22 percent for CBP and 21 percent for ICE. The House bill would actually cut total 2018 funding for the rest of the Department of Homeland Security a bit below 2017, although within that overall decrease there are pluses for various items and minuses for others.

The House appropriators also provided an increase for the Legislative Branch bill, although the amounts involved are considerably smaller. Including an allowance for Senate-specific items (which, by tradition, are not included in the House bill), the increase is $50 million or 1.1 percent. Part of that increase is to provide additional security measures for House and Senate members in light of the recent shooting of Rep. Steve Scalise.

The House committee cut non-defense funding for each of the remaining eight bills. Table 1 shows the reduction for each compared to 2017. In dollar terms, these cuts total $13.7 billion — the result of a BCA cap that is $2.8 billion below 2017, combined with House Republicans’ decision to hold non-defense appropriations $5 billion below that cap, and the need to offset $5.9 billion in increases in the three bills listed above. These dollar amounts are not adjusted for inflation; adding an inflation adjustment would bring the total cut to roughly $23 billion.

| TABLE 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 Funding Bills as Approved by House Appropriations Committee Non-defense discretionary budget authority subject to BCA caps, dollars in billions |

||||

| FY 2017 enacted | FY 2018 House | FY 2018 compared to FY 2017 | ||

| Dollar | Percent | |||

| Military Construction & Veterans Affairs | 74.7 | 78.6 | 3.9 | 5.3% |

| Homeland Security | 40.5 | 42.5 | 1.9 | 4.7% |

| Legislative Branch | 4.4 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 1.1% |

| Transportation & Housing | 57.4 | 56.2 | -1.1 | -2.0% |

| Interior & Environment | 32.3 | 31.5 | -0.8 | -2.6% |

| Labor, Health and Human Services, & Education | 161.0 | 156.0 | -5.0 | -3.1% |

| State Dept. & Foreign Operations | 36.6 | 35.3 | -1.2 | -3.4% |

| Including Overseas Contingency Operations | 57.4 | 47.4 | -10.0 | -17.4% |

| Energy & Water | 17.8 | 17.1 | -0.7 | -4.0% |

| Financial Services & General Govt | 21.2 | 20.2 | -1.0 | -4.9% |

| Commerce, Justice & Science | 51.4 | 48.7 | -2.6 | -5.1% |

| Agriculture | 21.1 | 20.0 | -1.1 | -5.3% |

| Total | 518.5 | 510.7 | -7.8 | -1.5% |

| 3 bills with higher funding | 119.6 | 125.5 | 5.9 | 4.9% |

| 8 bills with lower funding | 398.9 | 385.2 | -13.7 | -3.4% |

| Addendum: caps (current law) | 518.5 | 515.8 | -2.8 | -0.5% |

Note: Figures may not add due to rounding. Legislative branch funding includes allowance for Senate items.

Source: CBPP based on Congressional Budget Office and House Appropriations Committee

In addition to these cuts, the House Appropriations Committee’s bills would also cut non-defense funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) from $20.8 billion in 2017 to $12.0 billion in 2018. This funding is intended to meet the diplomatic and international assistance cost of dealing with conflicts in the Middle East and other trouble spots, and is not subject to the BCA caps. All non-defense OCO funding is included in the State Department and Foreign Operations appropriations bill. Including OCO, the overall cut to that bill grows to $10.0 billion or 17.4 percent.[3]

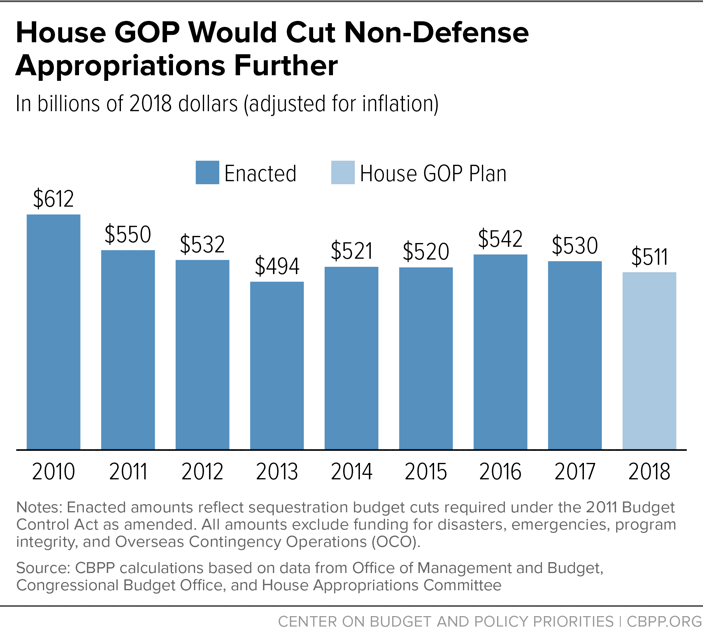

The cuts proposed for 2018 are particularly significant because they would follow seven previous years of tight constraints on non-defense appropriations. Those constraints have led to substantial funding reductions in many agencies and programs, and to erosion in many others as appropriations have failed to keep up with costs or needs. While there have been both ups and downs during this period, the cumulative effect has been considerable. Between 2010 and 2017, overall non-defense appropriations have decreased 13 percent after adjustment for inflation and 18 percent if also adjusted to reflect population growth. (See Figure 2.)

If the new round of cuts sought by the House majority is enacted, the cumulative reduction since 2010 would be 17 percent adjusted for inflation and 22 percent adjusted for both inflation and population.

Non-Defense Cuts and Shortfalls

Following are examples of the effects of these levels on important services and investments, drawn from the 2018 bills passed by the House Appropriations Committee at the reduced non-defense total favored by the House majority.[4] In some cases the effects involve substantial cuts below prior years’ levels. In other cases they simply involve funding that falls short of need. When making comparisons over periods longer than one year, these examples use inflation-adjusted dollars. While current inflation is relatively low it is still a significant factor — especially over multi-year periods — as rising costs for personnel, rent, equipment, and other necessary expenses gradually erode purchasing power.

These examples are illustrative rather than an attempt at a comprehensive list. They focus only on funding levels, and do not address the numerous problematic riders and legislative provisions also included in the bills.

Support for elementary and secondary education. The 2018 Labor-HHS-Education bill approved by the House Appropriations Committee would accelerate the erosion that has occurred over the past seven years in the modest but important support the federal government provides for local schools. The appropriations bill would cut overall funding for elementary and secondary education programs $2.3 billion (6 percent) below 2017, bringing the cumulative inflation-adjusted cut since 2010 to 20 percent.

Much of the House bill’s cut comes from eliminating grants to school districts to aid in recruiting, training, supporting, and retaining high-quality teachers — grants that received almost $2.1 billion in funding this year. In addition, the bill would eliminate funding for grants to improve literacy instruction ($190 million in 2017) and cut support for after-school programs in high-need schools. These and other elementary and secondary education programs were reauthorized just two years ago on a bipartisan basis in the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015.

About three-quarters of appropriations for elementary and secondary education go for two basic grant programs for local schools: “Title I” grants, which provide funding to more than half of all public schools for additional services and supports to help disadvantaged students succeed; and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) grants, which help cover the cost of special education services to meet the needs of more than 7 million children with disabilities. The House bill would provide a $200 million increase for IDEA — a bit short of what’s needed just to keep pace with inflation — but no increase at all for Title I.

Infrastructure for drinking water and wastewater treatment. The House appropriations bills would further diminish federal efforts to reduce water pollution and help ensure access to safe drinking water throughout the nation by assisting localities with capital needs for water treatment infrastructure. Needs for investment in this area are tremendous — to replace aging pipes, upgrade treatment systems, and correct problems such as wastewater and stormwater draining into the same sewers and overflowing in heavy rains. Capital investment required over the next 20 years totals $384 billion for drinking water systems and $271 billion for wastewater treatment, according to the EPA.[5]

The largest federal assistance comes in the EPA budget, primarily through contributions to state Clean Water and Drinking Water revolving loan funds. The House Interior and Environment appropriations bill would cut funding for the EPA water infrastructure programs $270 million below 2017,[6] continuing what generally has been a downward trend in federal water infrastructure funding over the past 15 or so years. On an inflation-adjusted basis, overall EPA water infrastructure appropriations under the 2018 House bill would be 28 percent below 2011 and 46 percent below 2001.

In addition, the Agriculture Department provides financial assistance for water infrastructure geared to the special needs of rural communities, which often have less financial and technical capacity and face higher costs because of smaller-scale operations. The House Agriculture appropriations bill would cut funding for this rural-focused assistance by $98 million (17 percent) compared to 2017, bringing inflation-adjusted funding 25 percent below 2008 (the year these programs became a separate account in the rural development budget).

Job training and employment services. Despite widespread recognition of the need to invest in job training programs to help workers gain the skills they need for good jobs in the current economy, the House Labor-Health and Human Services-Education appropriations bill would continue the trend of disinvestment in these programs. It would cut the three core formula grants that help states and localities provide employment services to adult, youth, and dislocated workers by $86 million compared to 2017. When combined with previous cuts and adjusted for inflation, the House bill would bring funding 23 percent below 2010 and 43 percent below 2001. These grants, reauthorized under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), offer a range of services including education, assessment, and skills training.

In addition, the bill would cut several non-formula grant programs, including elimination of grants to support expansion of apprenticeship programs (which received $95 million in 2017) and a $91 million (41 percent) cut to nationally administered funding that assists workers dislocated by events such as plant closings and natural disasters.

The House bill also would eliminate all Employment Service grants to states. These grants, which have existed since the 1930s and received $671 million in 2017, support a nationwide network that helps match job seekers to jobs through job postings and referrals, as well as provide related services such as case management, program evaluation, skills assessments, and career counseling. The Employment Service serves a critical role in the functioning of many states’ workforce system — it is required under the WIOA to serve as a front door at all comprehensive One-Stop centers, which let workers access career and employment services at a single location.[7]

Mental Health Block Grant. The House Labor-HHS-Education bill would cut the Community Mental Health Services block grant by more than one-quarter, from $563 million in 2017 to $421 million in 2018. This is a formula grant to states, which use the funds to assist local community mental health providers. The block grant is particularly important for services to people without health insurance, allowing providers to serve patients they know won’t be able to pay, and the funding cut would therefore be particularly harmful in the 19 states that have not expanded Medicaid. The block grant also pays for services not covered by private insurance or Medicaid, and fills important gaps like case management, outreach and engagement, and provider administrative costs.

Ironically, the House Appropriations Committee cut this basic safety net mental health program at the same time its leaders continue to express concern about the opioid use epidemic —thus ignoring the strong connection between mental health services and substance use treatment. In 2015, of the 19.6 million adults with a substance use disorder, 41 percent had mental illness of some type.[8] For people in that situation, their substance use can’t be treated in isolation from their mental health, making the mental health block grant an important element in addressing the opioid epidemic.

Rental aid for low-income households. While the House Appropriations Committee would provide a modest increase in funding for Housing Choice Vouchers — the largest program that provides rent aid to 2.2 million low-income households — it would defund the vouchers that 140,000 families are currently using.[9] Housing vouchers play a critical role in reducing homelessness, providing stable housing to low-wage working families, and helping seniors and people with disabilities afford homes that meet their needs. Cuts in housing vouchers would worsen homelessness and increase hardships for low-income households that are struggling to pay rent and make ends meet.

The cost of simply continuing the rental aid that families now receive grows every year, due mostly to rising rental costs in the private market. Constrained by the tight BCA limits, the modest funding increase included in the House Transportation and Housing bill would fall far short of what is likely to be needed to renew all vouchers next year. As a result, the bill would cut rental aid at a time when 3 out of 4 eligible low-income households already receive no help due to funding limitations, and nearly every community has long waiting lists for assistance.[10]

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Congress has cut the IRS budget sharply since 2010, and the House Appropriation Committee’s bill would reduce IRS funding by another $149 million. Adjusted for inflation, this would bring the IRS budget $2.9 billion below its 2010 level — a 21 percent cut.

The proposed cuts would be particularly damaging since they follow a multi-year squeeze on IRS resources. Funding pressure since 2010 has forced the agency to sharply reduce its workforce and delay long-overdue upgrades to information technology systems, harming customer service, compromising cybersecurity, and undermining efforts to combat tax avoidance and identity theft.[11]

Continued IRS cuts would further weaken the agency, embolden tax cheats, and harm honest taxpayers. Providing sufficient resources for enforcement is especially important this year, as Republicans aim to make fundamental changes to the tax system that would require significant IRS resources to implement.

Family planning. The House Labor-HHS-Education appropriations bill eliminates funding for the Family Planning program (often referred to as “Title X,” after the law that authorizes it). This program has existed since 1970, and received appropriations of $286 million in 2017.

The Title X Family Planning program makes grants to support voluntary family planning services, information and education, pregnancy testing and counseling, and related preventive health services such as screenings for cancer and sexually transmitted diseases. Of 91 primary grantees in 2015, 46 were state, local, or territorial health departments and the rest were private non-profit organizations of various types.[12] These grants supported a network of almost 4,000 sites that served more than 4 million people. Under the law, priority is given to clients from low-income families, with fees based on income and no charges to people with incomes below the poverty level. For many clients, Title X providers are their only ongoing source of health care and health education.

Child care. Appropriated funding for child care assistance would rise by just 0.1 percent ($4 million) under the 2018 Labor-HHS-Education bill approved by the House Appropriations Committee. That increase is considerably less than needed just to keep up with rising child care costs, let alone cover the additional costs of meeting strengthened health, safety, and quality standards mandated by bipartisan legislation enacted in 2014. The result would be fewer children served, at a time when that number has already been declining; the most recent data show 373,000 fewer children served in 2015 than 2006, which was the peak year for such assistance.[13]

Child care assistance is critically important to parents working at low-wage jobs, but fewer than 1 in 6 children eligible for child care assistance under federal law received help from this or related programs. Under the House bill, child care appropriations in 2018 would be a bit below their 2002 level, adjusted for inflation, even though the number of families in need of assistance has increased considerably since then.

Disease control and public health. The House Labor-HHS-Education appropriations bill would cut overall funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by $198 million (2.8 percent) below 2017.[14] CDC is the lead federal agency for detecting and controlling infectious diseases, responding to emerging crises like Zika, monitoring public health, and promoting efforts to prevent and alleviate chronic health problems such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. It does so, in part, by providing technical and financial assistance to state and local health departments that form the core of the national public health system.

The cut to CDC comes after a number of years of relatively stagnant funding for the agency — despite continuing concern about emerging infectious diseases and the need for more disease prevention efforts. On an inflation-adjusted basis, CDC funding in 2018 would be 12 percent lower than eight years earlier.

The 2018 House bill would make cuts to the CDC budget in areas such as immunization, control of emerging infectious diseases, tobacco use reduction, and environmental health. The bill would provide modest increases in a couple of areas involving public health preparedness. Even so, in 2018 the basic grants to states to help prepare for disease outbreaks and other public health emergencies would be 15 percent below the 2010 level in inflation-adjusted terms.

Decennial census. Budget constraints are hampering Census Bureau efforts to prepare for the 2020 decennial census — the full count of the U.S. population that the Constitution requires every ten years. These censuses are massive and complex undertakings that require extensive planning and preparation, including hiring and training hundreds of thousands of census takers, testing systems, developing address lists, acquiring the necessary equipment and technology, and opening local field offices to handle the logistics of the count.

At this point in the census cycle, appropriations are normally ramping up significantly. For example, at a comparable stage of preparation for the last census, 2008 funding for the Census Bureau was 79 percent higher than two years earlier, in 2006. Under the House Commerce-Justice-Science appropriations bill, however, 2018 Census Bureau funding would be only 10 percent above 2016. Inadequate funding has already caused the Census Bureau to cancel planned tests of 2020 Census methods. Without more adequate appropriations, as provided in previous cycles, census preparations will fall perilously behind schedule.

Renewable energy research and development. The House Appropriations Committee has assigned renewable energy research and development one of the largest cuts, as the Energy and Water appropriations bill would reduce funding for the Energy Department’s Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy account by almost $1 billion, from $2.1 billion in 2017 to $1.1 billion in 2018. By comparison, the lowest level previously appropriated for this account since it was established in its current form in 2008 was approximately $1.7 billion, in 2013.

This account supports research, development, demonstration, and deployment activities aimed at goals such as improving vehicle fuel efficiency and alternative fuel technologies, increasing generation of power from renewable sources, and reducing energy consumption in homes, buildings, and industry.[15] It also funds grants for weatherization of homes occupied by low-income families — a program the 2018 House bill would not cut.

Repair of federal buildings. The House Financial Services and General Government appropriations bill would reduce allowable funding for repair and alteration of federal buildings and courthouses from $676 million in 2017 to $180 million in 2018, eliminate funding for construction, and use the savings as an offset for other appropriations. These maneuvers involve the General Services Administration’s (GSA) Federal Buildings Fund, which collects market-based rents from agencies occupying buildings owned or leased by GSA. The rental income is supposed to be used, subject to appropriations, for construction and repairs, as well as operating costs and lease payments.

By sharply limiting the use of rental income for repairs and construction, the Appropriations Committee would produce an estimated $2.1 billion surplus in the Federal Buildings Fund in 2018 — a surplus that serves as an offset for other (unrelated) appropriations but increases the maintenance backlog. GSA reported deferred maintenance totaling $1.2 billion in 2016, representing work needing to be performed immediately to restore or maintain buildings in acceptable condition.[16] The GSA budget request for 2018 proposed $790 million for construction and $1.4 billion for repairs, making use of the full amount of rents collected.

End Notes

[1] In this paper, unless otherwise noted, comparisons of funding changes between 2017 and 2018 are not adjusted for inflation. Comparisons over longer periods do include inflation adjustments (unless noted).

[2] Those 11 include all the regular annual appropriations bills except the Defense bill. The Defense bill also includes a very small amount (about $130 million) of non-defense funding, but we haven’t included the bill in this analysis because it represents only about .03 percent of non-defense appropriations.

[3] The House bills also cut Defense OCO funding. The cut is $8 billion, but from a much larger base of $83 billion.

[4] Several of these examples involve agencies and programs discussed in a paper published by CBPP in May describing various areas where appropriations have been falling short of needs: David Reich and Chloe Cho, “Unmet Needs and the Squeeze on Appropriations,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 19, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/unmet-needs-and-the-squeeze-on-appropriations.

[5] Environmental Protection Agency, “Drinking Water Needs Survey and Assessment,” April 2013, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/epa816r13006.pdf; “Clean Watersheds Needs Survey 2012,” January 2016, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-

12/documents/cwns_2012_report_to_congress-508-opt.pdf.

[6] This includes a $250 million cut to the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, plus reductions to special purpose grants, and does not reflect funding provided in 2017 to help deal with the Flint, Michigan drinking water situation.

[7] For further details on the One-Stop delivery system, see: David H. Bradley, “The Workforce Investment Act and the One-Stop Delivery System,” Congressional Research Service, June 14, 2013, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41135.pdf.

[8] “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, September 2016, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf.

[9] Douglas Rice, “House Funding Bill Cuts 140,000 Housing Vouchers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 20, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-funding-bill-cuts-140000-housing-vouchers.

[10] Alicia Mazzara, “Housing Vouchers Work: Huge Demand, Insufficient Funding for Housing Vouchers Means Long Waits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 19, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/housing-vouchers-work-huge-demand-insufficient-funding-for-housing-vouchers-means-long-waits.

[11] For further details on the impact of IRS funding cuts, see Brandon DeBot, Emily Horton, and Chye-Ching Huang, “Trump Budget Continues Multi-Year Assault on IRS Funding Despite Mnuchin’s Call for More Resources,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated March 16, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/trump-budget-continues-multi-year-assault-on-irs-funding-despite-mnuchins.

[12] Information in this paragraph comes from the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Population Affairs, Title X Family Planning Annual Report, 2015 National Summary (August 2016), available at https://www.hhs.gov/opa/sites/default/files/title-x-fpar-2015.pdf.

[13] Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Child Care, “Child Care and Development Fund Statistics,”https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/ccdf-statistics. These figures also include assistance provided through related funding provided on the mandatory side of the budget.

[14] Figures given in this section for CDC funding include both regular appropriations and additional amounts provided through the Prevention and Public Health Fund, but not supplemental funding provided from time to time to deal with particular emergencies such as the Ebola and Zika epidemics.

[15] For more information on these programs, see https://energy.gov/eere/about-office-energy-efficiency-and-renewable-energy.

[16] General Services Administration, FY 2018 Congressional Justification (May 23, 2017), page FBF-3, https://www.gsa.gov/portal/getMediaData?mediaId=162214.

More from the Authors