Existing Medicaid Flexibility Has Broadened Reach of Home- and Community-Based Services

Testimony of Judith Solomon

Vice President, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Before the Health Subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am Judith Solomon, Vice President for Health Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, an independent, non-profit, nonpartisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s health work focuses on Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and Medicare. I have spent over 35 years working on Medicaid, beginning as a legal services attorney representing clients and in several positions focusing on Medicaid policy issues affecting children, seniors, and people with disabilities.

The three bills before you would make changes to various aspects of the Medicaid program, including the process for verifying citizenship, eligibility for people receiving certain lump-sum income including lottery winnings, and the eligibility of seniors who purchase annuities for their benefit of their spouses. As I understand it, an amount equal to the projected federal savings resulting from these bills would be transferred to the Medicaid Improvement Fund. Monies in the Fund would then be used to provide funding at a 90 percent federal match to a select group of states to reduce their waiting lists for home- and community-based services. The criteria for selecting the states would be based on the size of the state’s waiting list, how long people remain on the list, and the incomes of people on the waiting list, with preference given to states with lists including the lowest-income people. As I will explain later in my testimony, while we support the goal of decreasing HCBS waiting lists, there are better ways to help states make progress in this regard.

Medicaid HCBS Services: Background

Later in my testimony, I discuss our concerns regarding two of the bills, but I would like to start by providing some background information on how Medicaid provides home- and community-based services (HCBS) for millions of vulnerable individuals, and more specifically why some states have waiting lists for people applying to receive these services. I especially want to address the claim that the Medicaid expansion has resulted in longer waiting lists and kept vulnerable people from getting the services they need. As I will explain, while waiting lists are something we all would like to eliminate and avoid in the future, they are a direct result of state choices on the design of their Medicaid programs and the amount of resources states make available to provide HCBS. There is no evidence that states are choosing to expand Medicaid or keep their expansions at the expense of vulnerable people waiting for HCBS, and examining state choices on both expansion and HCBS waivers actually leads to a contrary conclusion.

HCBS waivers became available in 1981 to provide states with a way to provide long-term services and supports (LTSS) outside of institutions. Skilled nursing care and home health services are mandatory services in Medicaid, but because many individuals need additional services beyond home health to stay in their homes Medicaid was biased toward institutional care. Families often had to face the dilemma that the only way they could get their loved ones the care they needed was to put them in a nursing home. The choice was especially difficult for parents of children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities who needed significant supports to stay at home.

HCBS waivers gave states new ways to address the LTSS needs of their residents, including children, adults with disabilities, and seniors, leading to a dramatic shift in the program since 1981. Using HCBS waivers, states can make people eligible for Medicaid who were previously only financially eligible if they were in a nursing home or other institution. States can also create packages of services specifically designed to keep people in their homes, including home modifications, respite care for family caregivers, and enhanced home health services.

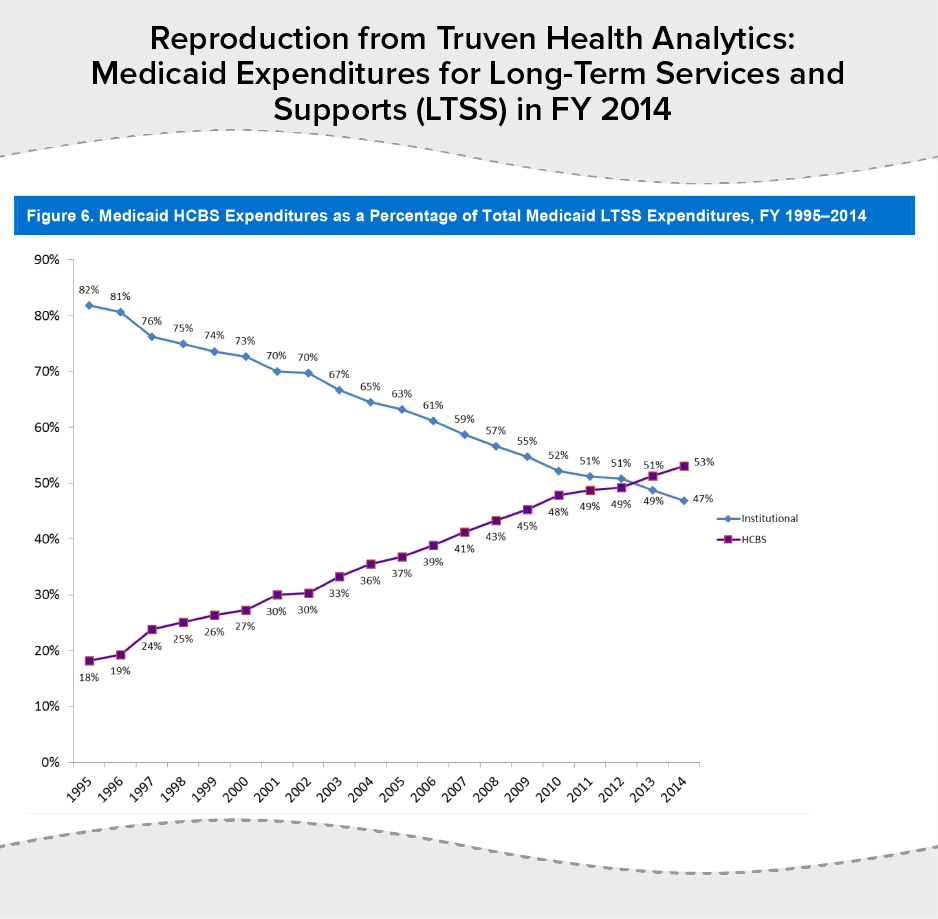

In 2013, for the first time, over half of LTSS expenditures were for HCBS rather than for institutional care. Progress has been dramatic, with the share of LTSS spending on HCBS climbing from 18 percent in 1995 to 53 percent in 2014.[1] (See Figure 1.)

HCBS Waivers Demonstrate Medicaid’s Existing Flexibility

HCBS waivers are responsible for much of the progress in moving care out of institutions into homes and the community, and they are the epitome of how Medicaid provides states with flexibility to design their own programs. States can target waivers to particular groups such as people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, seniors, people with HIV/AIDS, and people with traumatic brain injury, and create packages of services specifically designed to meet the needs of certain groups. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), there are currently more than 275 waiver programs active nationwide serving well over 1 million individuals.[2]

Part of the flexibility states have is to limit their HCBS waivers to a defined number of slots, and to create waiting lists once those slots are filled. States can also increase or decrease the number of slots by submitting amendments to CMS, and they can keep slots open if state funding isn’t sufficient to fill them. This flexibility is important for states, because waiver services can be costly, although on average waiver services are cheaper than care in a nursing home. In 2013, the total expenditures per person for all waiver types was $27,768, with waivers for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities the most expensive at $46,644 and waivers for people with HIV/AIDS the least expensive at $4,072 per person. [3]

Unlike nursing home care, which must be provided to all financially eligible beneficiaries who meet functional and medical criteria for skilled nursing care, states determine eligibility criteria for HCBS waivers and the services that are provided through the waivers. States can control their expenditures based on their fiscal and organizational capacity to support their initiatives and the budget decisions made by their legislatures. The availability of providers to provide the necessary services and supports can also influence state decisions on the number of available waiver slots.

Data on HCBS waivers show enormous state variation, which is evidence of the flexibility Medicaid provides. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured has tracked Medicaid HCBS programs over the last 15 years. The Commission’s most recent report looks at expenditures and participants in state programs in 2013, although it includes data on waiting lists through 2015.[4]

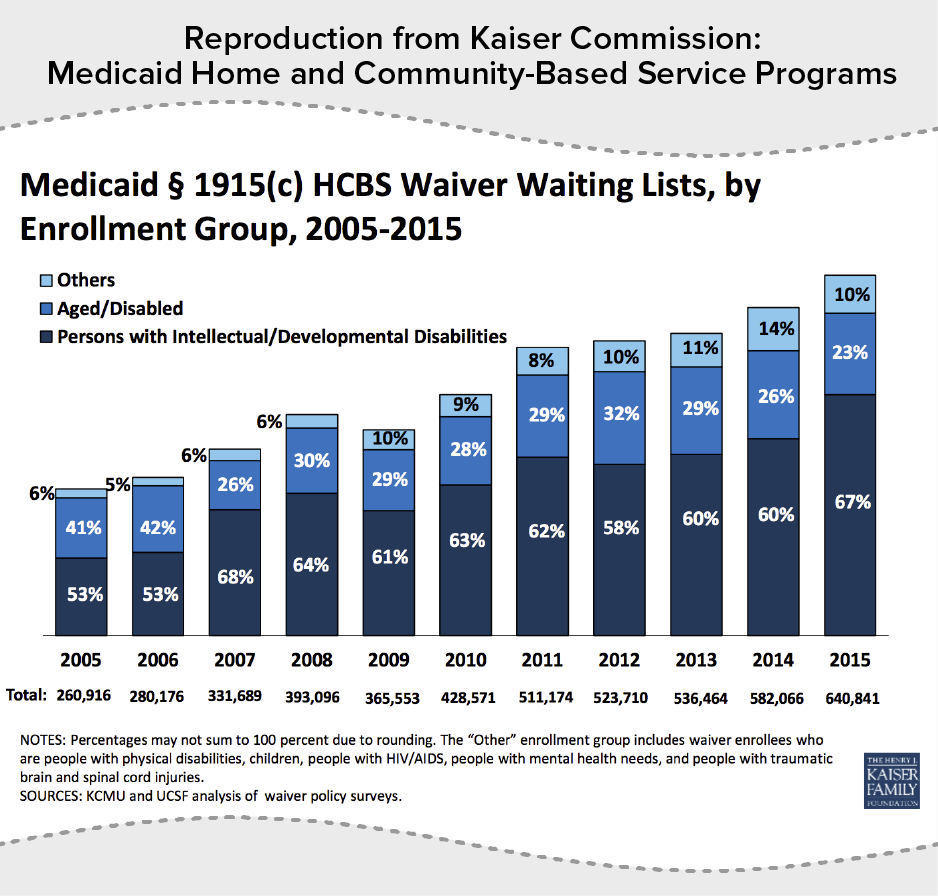

The number of people on waiting lists shows the growing demand for HCBS. Waiting lists have grown every year, increasing over the period from 2005 — well before the start of the Medicaid expansion — to 2015 by an average rate of 14 percent a year. (See Figure 2.)

There is significant variation across states, with 11 states and the District of Columbia having no waiting lists at all. Of these states without waiting lists, only two — Maine and Missouri —haven’t expanded Medicaid.[5] The two states with the longest waiting lists are Texas and Florida, which have not expanded Medicaid. In fact, Texas’ waiting list of over 204,000 individuals represents almost one-third of all people on waiting lists in 2015.[6] Moreover, the number of people in Texas enrolled in HCBS waivers has declined by 38 percent over the last ten years, and this decrease may be contributing to the size of its waiting list.

As noted, expenditures for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are the highest of all waiver types, and over two-thirds of people on waiting lists in 2015 were in this category. For example, only California had a waiting list for people with HIV/AIDS in 2015, amounting to just 65 people.

Another fact that is overlooked in discussions of waiting lists is that the vast majority of people on the lists — 93 percent for waivers for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and 100 percent for seniors — are enrolled in Medicaid and receiving all medically necessary services available from the state’s program other than waiver services. These individuals are Medicaid beneficiaries, and they are able to get home health services, personal care services if covered under the state’s plan, and of course prescription drugs and the full range of medical and specialty care Medicaid covers. This is not to say that they don’t have a need for the additional HCBS waiver services that should be addressed, but just to make it clear that the waiting list is to receive the additional package of waiver services, not for services covered by the Medicaid program.

ACA Added Options for States

It’s also important to note new options and incentives states received in the ACA, which are contributing to the shift from institutional care to care in the community. Similar to HCBS waivers, states have made their own decisions whether to take up these new options, some which provide grant funding to help states rebalance their programs away from institutional care.

The ACA made significant improvements to an option first added to the Medicaid statute in 2005 by allowing states to target services to particular populations and making other changes that help states address the needs of people with behavioral health conditions who aren’t eligible for HCBS waivers. Under this option, states can provide HCBS under their state plans rather than through a waiver, and 18 states have taken up this option. Unlike HCBS waivers, states must cover all those who meet the eligibility requirements defined in the state plan, which means that states can’t have waiting lists when they take up the HCBS option. Of the 18 states that have approved state plan amendments for HCBS services, 14 have also expanded Medicaid, again showing that state decisions on HCBS and expansion are independent and instead depend on state decisions regarding how they want to serve their residents.[7]

The ACA also provided grants to states to help them rebalance their programs through the Balancing Incentive Program, a continuation of the Money Follows the Person program, which helps people transition from institutional care to the community, and the Community First Option to provide attendant services and other supports through the state plan rather than through waivers.

Bills Before the Subcommittee Aren’t Best Way to Extend HCBS to More Individuals

There is broad support for the goal of decreasing state waiting lists for HCBS — and CBPP is highly supportive of this goal — but there are better ways to address the waiting lists than by taking savings from the three bills before you to provide enhanced federal matching funds to states with the longest waiting lists. It would be much fairer to all states to provide incentives to enhance the provision of HCBS, which could include metrics to measure state progress. For example, while Texas has by far the longest waiting list for HCBS, it did participate in several of the ACA-provided options, including the Balancing Incentive Program and the Community First Choice Option. Providing increased resources through these types of program is aligned with the overall structure of the Medicaid program to provide states with an array of choices to meet their needs. Moreover, it avoids having states forgo their own efforts to reduce their waiting lists in order to get a chance to get 90 percent match available to states with the longest waiting lists.

I would like to address two of the bills before you, starting with the “Verify Eligibility Coverage Act.” We have significant concerns regarding this bill, because we think it will leave many eligible U.S. citizens without coverage. People must be U.S. citizens or have an eligible immigration status in order to be eligible for Medicaid, and their citizenship or immigration status must be verified. When completing applications, U.S. citizens must attest that they are citizens. The vast majority of applicants provide their Social Security number, which is used along with other personal information to complete an electronic data match with Social Security Administration (SSA) records to verify U.S. citizenship. Citizenship of a vast majority of applicants is successfully verified through the data match, but there are cases where the match isn’t successful. When this happens, applicants have to send in documents to prove they are U.S. citizens. If applicants have satisfied all other eligibility requirements such as having income within the state’s eligibility limits, the applicant receives Medicaid during a defined time period that is referred to as a reasonable opportunity period. States get federal funding for Medicaid provided during the reasonable opportunity period.

The bill being considered today would end federal funding for Medicaid benefits provided during a reasonable opportunity period for applicants who have not had their U.S. citizenship verified. As noted, the vast majority of applicants attesting to U.S. citizenship have their citizenship verified through the electronic data match with SSA. Naturalized citizens and adult citizen applicants born abroad are the groups most likely unable to have their citizenship verified by SSA. This would include people who were born to members of the U.S. military serving abroad before 1972 when Social Security began including citizenship information in its records.

The savings from this bill would largely result from delays or denials of eligibility for eligible people, especially naturalized citizens. Under legislation enacted in 2006, states were required for several years to ask families to present proof of their citizenship and identity — generally by producing a birth certificate or passport — when they applied or renewed their Medicaid coverage. In the eight months after this requirement took effect, states reported large declines in Medicaid enrollment, particularly among low-income children. This requirement was subsequently modified to allow states to use Social Security Administration databases to confirm citizenship or eligible legal immigrant status in most cases and to provide a reasonable opportunity period to provide documents to those who couldn’t successfully verify their citizenship through the electronic match understanding that it takes time to provide documentation for the small group of people whose citizenship can’t be verified through Social Security.

I would also note that the language of the bill refers to “aliens,” who are individuals “declaring to be a citizen or national of the United States.” Legal immigrants applying for Medicaid must prove they have a status that qualifies them for the program. There are strict rules for verifying their status found in a separate part of the Social Security Act. So despite the reference to aliens, this bill would affect people who are citizens.

The second bill is “The Prioritizing the Most Vulnerable Over Lottery Winners Act of 2017.” The current version of this bill is a vast improvement from where it started in 2015. As we wrote in a paper then, the earlier version would have undermined the streamlined, coordinated eligibility approach that health reform established for Medicaid and marketplace subsidies and would have resulted in a number of low-income people who would otherwise be eligible, including people with disabilities, becoming uninsured.[8] The bill still raises concerns, however, as to its impact on the streamlined enrollment process and coordination with the marketplace. It will require new questions on the application and new tracking by states for what may be a limited return. Michigan’s current Medicaid expansion waiver allows the state to garnish state tax refunds and lottery winnings to recoup unpaid premiums and cost-sharing from participants in the program. In all of 2015 and through the third quarter of 2016, the state collected a total of $380.67 from just six lottery winners.[9] It is certainly possible that the payments to Michigan’s contractor to collect these amounts exceeded the amount collected.

Threats Posed by Changing Medicaid’s Structure

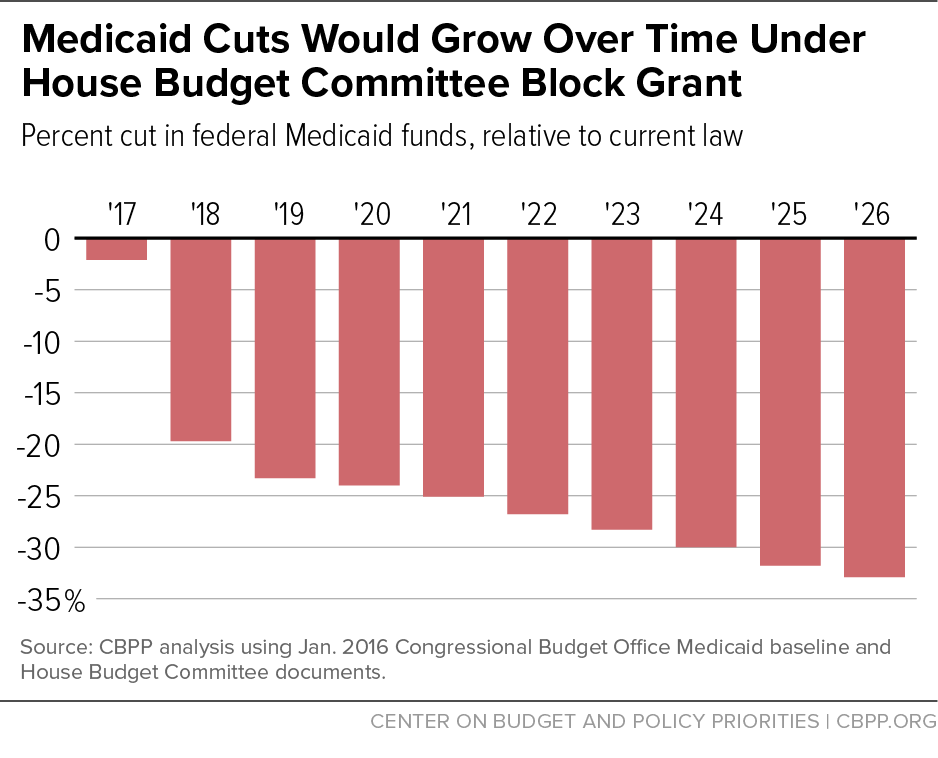

In closing, I would like to note the real threat other Medicaid proposals present to HCBS services in contrast to the Medicaid expansion, which is not responsible for waiting lists. While not before the Committee today, President-elect Trump, House Speaker Paul Ryan, and Health and Human Services Secretary nominee Tom Price support radically changing the Medicaid program’s basic structure by converting the program to a block grant or what is known as a “per capita cap” and reducing federal funding for the program over time. The most recent House budget plan (for fiscal year 2017), would have given states the choice of a block grant or per capita cap in order to achieve cuts in federal Medicaid funding of about $1 trillion over ten years and even more in the decades after that. These cuts would be in addition to repealing the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, which would withdraw roughly another $1.1 trillion in federal Medicaid funding for states over ten years. (See Figure 3.)

Cuts of this magnitude would likely lead to huge increases in HCBS waiting lists or elimination of HCBS waivers altogether in many states. As states consider how to deal with these cuts, it is unlikely that they would risk terminating coverage for people in nursing homes, who could suffer serious harm or even death should they lose their coverage. Moreover, states would not be able to make the upfront investments often needed to expand their capacity to provide HCBS.[10] With deep cuts in federal funds, it is far more likely that states would cut HCBS and other services for people in the community, reversing the admirable progress states have made since the inception of HCBS waivers in 1981 to allow families to keep their loved ones at home.

Policy Basics

Health

End Notes

[1] Truven Health Analytics, “Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2014,” April 15, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/ltss/downloads/ltss-expenditures-2014.pdf.

[2] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid & CHIP: Strengthening Coverage, Improving Health, January 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/downloads/accomplishments-report.pdf.

[3] Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Programs: 2013 Data Update,” October 2016, http://kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-programs-2013-data-update/.

[4] Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2016.

[5] The other states besides the District of Columbia without waiting lists are Delaware, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Michigan, North Dakota, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, and Washington.

[6] Table 14 of the 2013 data update.

[7] The four non-expansion states are Florida, Idaho, Mississippi, and Wisconsin, and the 14 expansion states are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, Ohio, and Oregon.

[8] January Angeles, “House Medicaid Bill Would Result in More Uninsured Low-Income Individuals and Families, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 9, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/house-medicaid-bill-would-result-in-more-uninsured-low-income-individuals-and.

[9] “Michigan Adult Coverage Demonstration Section 1115 Quarterly Report: Third Quarter 2016,” January 17, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/mi/Healthy-Michigan/mi-healthy-michigan-qtrly-rpt-jul-sep-2016.pdf.

[10] Judith Solomon, “Caps on Federal Medicaid Funding Would Give States Flexibility to Cut, Stymie Innovation,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 18, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/caps-on-federal-medicaid-funding-would-give-states-flexibility-to-cut-stymie

More from the Authors