BEYOND THE NUMBERS

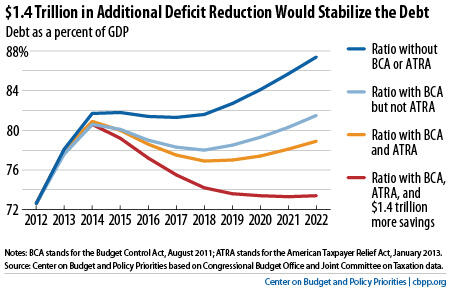

CBPP estimates that $1.4 trillion in additional deficit savings — on top of those in the 2011 Budget Control Act, the recent “fiscal cliff” tax deal, and other legislation — would stabilize the public debt as a share of the economy over the next decade (see graph), though this would not be enough to address our longer-term budget problem.

Some groups, while agreeing with our $1.4 trillion estimate, argue that more deficit reduction over the next decade is essential. We disagree for several reasons, and two in particular.

First, the single biggest cause of the nation’s long-term budget problems is the fact that per-capita health care costs are growing faster than the economy and are expected to continue doing so. Right now, solutions to slow health care costs without reducing health care quality or impeding access to needed care remain elusive.

Under health reform, demonstration projects and other experiments to find ways to do so are now starting. By later in the decade, we should know much more about what works and what doesn’t. An additional $1.4 trillion in deficit reduction would buy time to find answers to these important questions. Taking major new steps to reduce health spending now, before we have the necessary knowledge and experience, could compromise health care quality or harm large numbers of sick or otherwise vulnerable individuals — and might not even control costs effectively.

Second, some analysts argue that stabilizing the public debt at 73 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) — by enacting another $1.4 trillion in deficit reduction — would be insufficient, and that we should aim to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. But no economic evidence supports any specific debt-to-GDP target.

The International Monetary Fund adopted a target of 60 percent of GDP some years ago, but IMF staff have made clear that the 60 percent criterion is an arbitrary one. And, even if such a target were the best one before the Great Recession drove up debt levels, it wouldn’t necessarily be appropriate over the next ten years, given the severity of the downturn and the economy’s continued weakness.

While it will not permanently solve our fiscal problems, stabilizing the debt during this decade would represent an important accomplishment, ensuring that the debt doesn’t grow faster than the economy and risk eventual economic problems. Another $1.4 trillion in deficit reduction, in combination with the measures already enacted, would make the overall deficit-reduction package as large as the 1990 deficit agreement as a share of the economy and larger than that of 1993 — the two big budget deals that played an important role in converting the large deficits of the early 1990s to four years of budget surpluses that began in 1998.