BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As the New York Times’ 20-year retrospective on welfare reform shows, states haven’t used their flexibility under the 1996 welfare law (which created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families block grant, or TANF) to prepare the poorest families for work or provide an adequate safety net when they can’t work.

Instead of investing more to connect families to work and developing innovative strategies for families with serious employment barriers, states have shifted billions of dollars of TANF funds to other uses while providing basic cash assistance to fewer and fewer needy families.

Ron Haskins, a key architect of the 1996 law as a senior Republican House staff member, told the Times, “I have to say that what has happened with welfare reform has caused me to reevaluate my confidence that the states will do the right thing.”

Our detailed 2015 examination of state TANF spending shows that:

-

States spend only about a quarter of their federal and state TANF dollars on child care and work activities combined. A key justification for block-granting TANF was to enable states to move funding from cash assistance to work-related activities and supports, such as child care subsidies. States raised spending in these areas in TANF’s early years but didn’t sustain those modest increases. All told, states used only 8 percent of their combined federal TANF funds and state “maintenance of effort” funds for work activities in 2014, and 16 percent of those combined funds on child care.

Some states spend even less. As the Times notes, for example, Arizona spends only 7 percent of its federal and state TANF funds on work activities and child care put together.

-

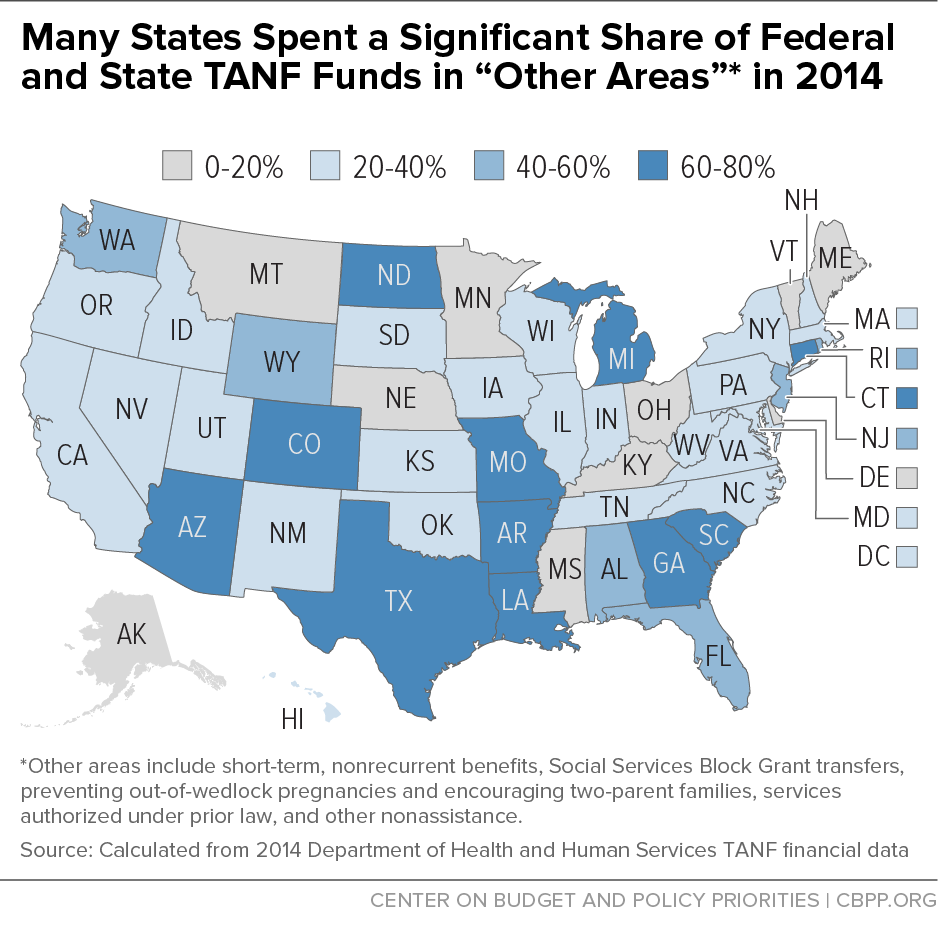

States spend a large and growing share of their TANF funds outside the core welfare reform areas of basic assistance, work activities, and work supports. Nationally, states spend 34 percent of their TANF dollars outside these three areas, mostly for child welfare; for 11 states, the figure is over 60 percent (see map).

In some cases, states have used TANF funds to expand programs or cover the growing costs of existing services. In other cases, they’ve used these funds to replace state funds, thereby freeing those state funds for purposes unrelated to providing a safety net or work opportunities for low-income families.

The Times also notes that states have dramatically scaled back TANF cash assistance and now help a much smaller share of poor families meet basic needs. Just 23 of every 100 poor families receive cash assistance, down from 68 of every 100 poor families when TANF was created. In a dozen states, fewer than ten in 100 poor families receive cash assistance.

Policymakers should keep states’ poor performance under TANF in mind when evaluating proposals to expand state control over other parts of the safety net.