BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Since the Trump Administration issued new rules last year expanding short-term health plans, which are exempt from the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) benefit standards and protections for people with pre-existing conditions, a dozen states have strengthened their own limits and consumer protections for short-term plans. Others should follow suit.

The new federal rules define short-term plans as those lasting less than a year, up from three months under the previous rules, and let insurers extend them for longer. That lets a market for skimpy plans operate alongside the market for comprehensive individual health insurance, exposing consumers to new risks and raising premiums for those seeking comprehensive coverage — especially middle-income consumers with pre-existing conditions.

Short-term plans don’t have to cover all of the ACA’s essential health benefits, and they often don’t cover such essential benefits as maternity and mental health care, substance use disorder treatment, and prescription drugs. They can also deny coverage or charge higher prices to people with pre-existing conditions, and they typically don’t cover medical services related to a pre-existing condition.

Short-term plans can offer healthier people lower premiums (because they include fewer benefits and cover less costly populations), so they lure healthy enrollees away from the individual and small-group markets, leaving a less healthy and thus costlier group behind. This dynamic, known as adverse selection, will likely raise premiums for traditional, more comprehensive health coverage and undermine ACA protections for people with pre-existing conditions. Meanwhile, healthy people who enroll in short-term plans may face gaps in coverage and catastrophic costs if they get sick and need care.

The rules took effect in early October, just before the November 1 start of the ACA’s open enrollment period, creating confusion for consumers because they had limited time to sign up for comprehensive 2019 ACA plans and were subjected to heavy marketing from companies selling short-term plans as an alternative.

A federal court upheld the Administration’s final rules in what’s expected to be an ongoing legal battle. Fortunately, states can set their own standards for short-term plans, and some have done so since the new federal rules came out.

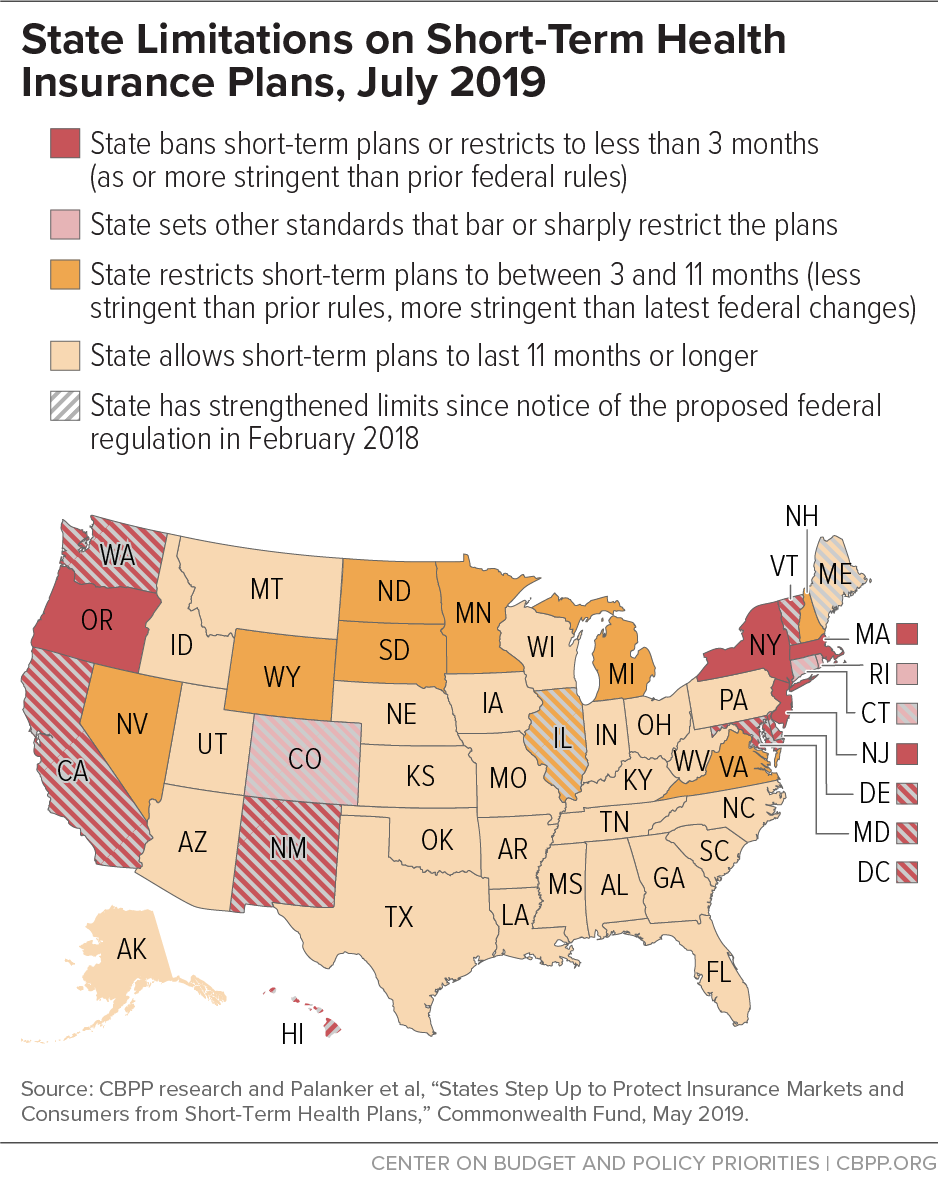

- California banned short-term plans, barring health insurers from issuing, selling, or renewing them within the state.

- Colorado, which already had limited short-term plans to six months, required them to be available to consumers regardless of their medical history, to limit their age-related premium differences so that the oldest adults pay no more than three times what younger adults pay, and to cover the ACA’s essential health benefits, among other changes.

- Connecticut barred short-term plans from excluding enrollees’ pre-existing conditions from coverage, a prohibition that previously applied only to short-term plans that lasted longer than six months. The state also requires short-term plans to cover the ACA’s essential health benefits.

- Delaware limited short-term plans to three months, with no extensions or renewals, and required them to spend at least 60 percent of consumers’ premium payments on medical care.

- The District of Columbia limited short-term plans to three months, restricted insurers from excluding coverage of pre-existing conditions, and barred insurers from selling the plans to someone who had a short-term plan within the prior nine months.

- Hawaii prohibited insurers from issuing a short-term plan to someone who was eligible for coverage through the ACA marketplace during an open or special enrollment period the prior year. It also limited short-term plans to less than 91 days and prohibited extensions or renewals.

- Illinois limited short-term plans to six months, restricted extensions and renewals, and required warning language for consumers.

- Maine required short-term plans to end no later than December 31 of the year when they’re issued, prohibited short-term plans from being marketed or sold in the state during the ACA’s annual open enrollment period, required brokers that sell them to check for and inform applicants when they may be eligible for ACA marketplace subsidies, and allowed the plans to be sold only in person.

- Maryland limited short-term plans to less than three months and prohibited extensions or renewals of short-term plans.

- New Mexico defined short-term plans as nonrenewable and lasting no more than three months.

- Vermont limited short-term plans to three months, prohibited renewals and extensions, and established minimum financial, marketing, and other standards for the plans.

- Washington State limited short-term plans to three months, with no renewals, and set requirements about the information insurers must give consumers about plan limitations.

Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York already had effectively prohibited short-term plans, and Rhode Island’s standards (including no pre-existing condition exclusions and a requirement to spend at least 80 percent of premiums collected on medical care) have blocked short-term plans in that state. Oregon already limited short-term plans to three months and restricted renewals. Several other states have protections that may mitigate the effects of the federal rule changes. (See map.)

Yet most states lack sufficient protections against potential adverse selection due to the federal rule change, as well as to Administration changes that promote association health plans and expand health reimbursement arrangements. Meanwhile, some states are moving in the wrong direction: Indiana, for example, rolled back the state’s six-month limit on short-term plans, as did Arizona.

Despite Administration efforts to undercut the ACA, states retain broad authority to protect consumers and create a level playing field for insurers in their individual and small-group markets — and insurers, patient groups, and consumer advocates have urged them to exercise it. States that haven’t yet acted should do so.