BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The Wall Street Journal’s recent editorial attacking the federal Pell Grant program, which helps low-income students afford college, was rife with misleading and inaccurate statements. For example, the editorial (based on a paper from the conservative John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy) claims that 60 percent of college students receive Pell Grants — double the actual figure of about 30 percent. Below are some basic facts that the editorial ignores, distorts, or turns upside down.

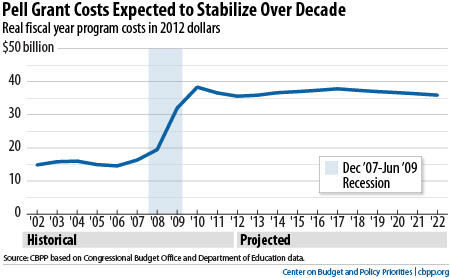

- Pell Grant costs are projected to stay flat over the next decade. Contrary to the editorial’s portrayal of Pell Grant spending as out of control, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projects almost no increase in program costs over the next decade, after adjusting for inflation (see graph).

Image

To be sure, Pell Grant costs rose substantially between 2008 and 2011. But that increase reflects modest eligibility expansions that Congress approved on a bipartisan basis to encourage more low-income students to get a college degree; increases in the maximum Pell Grant award that offset only a small part of the grant’s long-term decline in purchasing power; and the economic downturn, which has depressed family incomes and led more people — including people who have lost their jobs — to pursue college in order to improve their education and skills. - Pell Grants are targeted to needy students. Three-fourths of all Pell Grant recipients in 2010-11 had family income of $30,000 or less, according to the most recent data.

The editorial claims that the increase in Pell recipients has shifted the program away from serving the most disadvantaged students. But the biggest reason more students now qualify for Pells is that more students have financial need.

The editorial and the Pope Center paper also imply that better-off students can procure larger Pell Grants by attending costly institutions. That’s another egregious error: the program considers a student’s cost of attendance in determining Pell Grant eligibility only when that information shrinks the size of the grant for which the student can qualify — namely, when the cost is less than the maximum Pell Grant.

- Pell Grants help students attend and complete college. The Pope Center report argues that Pell Grants haven’t been effective in helping students who get into college actually get their degree. While gains in college graduation rates in recent decades have been relatively small for the poorest students, this is not the fault of Pell Grants. Students who qualify for Pell Grants are more likely than other students to face significant hurdles to completing college, such as single parenthood and lack of financial support from their own parents.

If you control for these risk factors, Pell Grant recipients who get their degrees do so faster than other students, a Department of Education study found.

- Pell Grants are not responsible for tuition increases. The evidence simply doesn’t support the editorial’s claim that “student aid raises tuition.” Education experts, including economists Sandy Baum and Bridget Terry Long, find no convincing evidence that Pell Grants raise tuition. The few research studies that show a link between financial aid and tuition increases only apply to private and for-profit institutions, which relatively few Pell Grant recipients attend. Indeed, public institutions — which educate over 60 percent of all Pell Grant recipients — are much more likely to increase tuition in response to reductions in state funding.

While the share of Pell Grant recipients at for-profit schools is on the rise, the Department of Education now requires these institutions to improve student outcomes if they wish to remain eligible for federal student aid — a policy to hold institutions accountable without punishing students.