BEYOND THE NUMBERS

With Republican presidential candidates gathering Saturday to discuss poverty and opportunity in Columbia, South Carolina, three points (highlighted in CBPP’s chart book on the safety net) are worth keeping in mind:

-

Because of a stronger safety net, poverty has fallen significantly since the War on Poverty was launched. The poverty rate appears similar today to its late-1960s level only if it’s measured without considering the effects of tax credits and many government benefits. That, however, would be a seriously misleading comparison, as it would entirely omit the effects of the main changes made in government assistance over this period, such as the creation of a national Food Stamp Program (now called SNAP), the introduction of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the like. Those benefits boost families’ income and purchasing power, and once they are taken into account, the poverty rate is found to have fallen substantially.

Our new analysis, which takes the landmark research on these matters conducted by a Columbia University research team and updates it through 2014, shows that under a more comprehensive measure of poverty (known as the anchored Supplemental Poverty Measure) that counts these benefits and makes other adjustments to the poverty measure that many analysts favor, the poverty rate fell from 26 percent in 1967 to 16 percent in 2014. Our analysis also finds that the effectiveness of the safety net grew nearly ten-fold over this period; in 1967, safety-net assistance lifted out of poverty 4 percent of those who would otherwise be poor, while in 2014, it lifted out 42 percent of those who would otherwise be poor.

-

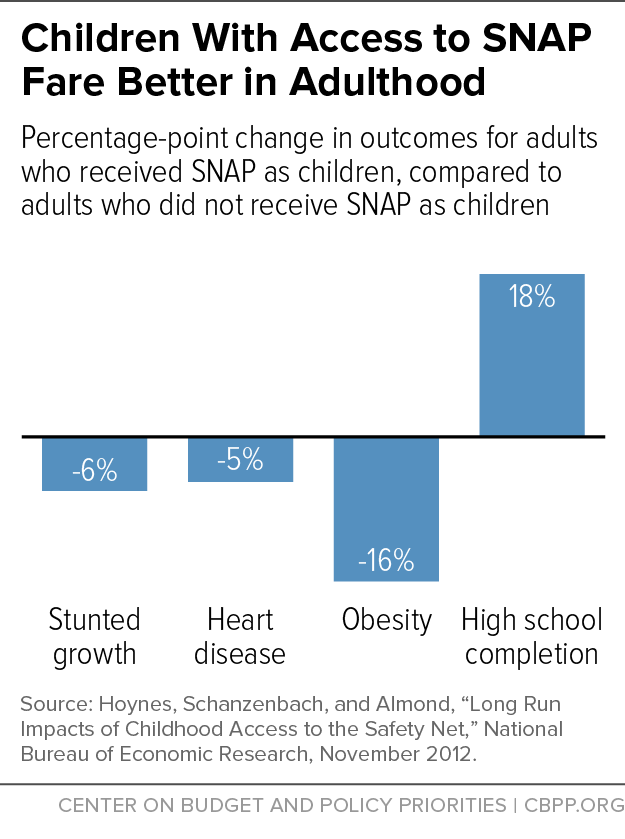

A growing body of research also finds that anti-poverty programs can produce long-term gains for children, thereby promoting opportunity and mobility. For example, after the Food Stamp Program was rolled out in stages across the country in the 1960s and 1970s, children from less-educated families who spent their early years in counties where food stamps were available were an impressive 18 percentage points more likely to finish high school than peers without access to food stamps. Children with access to food stamps also had significantly lower rates of stunted growth, obesity, and heart disease as adults, among other gains (see graph).

In addition, studies link the EITC to an increased likelihood of children being born at a healthy birth weight, having higher reading and math test scores in school, being more likely to go on to college, and having higher earnings in adulthood.

Well-designed rental assistance is another example. Pathbreaking research released last spring found that low-income young children whose families were living in public housing and used rental vouchers to move to low-poverty neighborhoods fared better in various respects — such as earning 31 percent more by age 26 — than similar children whose families were not assigned vouchers under the demonstration project. The findings underscore the importance of housing vouchers for helping low-income children — particularly low-income African American and Hispanic children, who are more likely than other children to live in neighborhoods of extreme poverty — to grow up in better neighborhoods and improve their long-term chances of success.

-

Nevertheless, the United States does less to combat poverty than most other wealthy nations, a key factor contributing to a higher poverty rate here. Many other wealthy nations have poverty rates similar to (or even higher than) the United States before factoring in the safety net but lower poverty rates (sometimes much lower) after counting it. That’s because nearly all of them do more to fight poverty: their programs are more generous, more accessible, and broader in scope than those in the United States.