BEYOND THE NUMBERS

In today’s New York Times “Room for Debate,” Michael Boskin defends the proposal to slash North Carolina’s income tax and help pay for it with a bigger sales tax by trotting out the theoretical argument that a consumption tax (such as a sales tax) is always and everywhere better than an income tax for an economy. Let’s review the arguments why that’s not true in the real world of state tax policy.

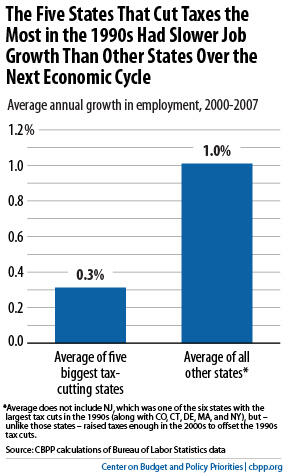

- Recent history shows that deep cuts in income taxes don’t fuel growth. The five states that enacted the deepest tax cuts during the boom years of the middle and late 1990s saw job growth over the next full economic cycle (2000-2007) of less than 0.3 percent per year, on average, compared to 1.0 percent for the other states (see chart). They also had slower income growth than the rest of the nation on average. Six out of eight recent academic studies of state income taxes confirm that differences in state income tax rates don’t affect economic growth.

- Replacing income tax revenues with an expanded sales tax would tilt state taxes against middle- and lower-income households. Cutting the income tax disproportionately benefits high-income families, since they generally face higher tax rates. Raising the sales tax hits low- and middle-income families the hardest, since they pay a bigger share of their incomes in sales tax than wealthier families do. This shift in the tax burden toward less-well-off families would worsen income inequality — and North Carolina has a wide gap between the rich and the rest.

- Cutting personal income taxes in favor of bigger sales taxes would weaken revenue without eliminating volatility. Both income and sales tax collections rise and fall with the economic cycle. But, taking both periods of growth and decline together, income taxes grow enough over time to fund normal expenditure growth and meet the evolving needs of residents and businesses. Sales taxes don’t.

Specifically, a 1 percent growth in total personal income generates more than 1 percent growth in income tax revenue because, in most states, people’s tax rate rises as their income rises. In contrast, sales taxes generally grow less than 1 percent for each 1 percent increase in income, largely because a growing share of purchases consists of services, which are largely untaxed.

Boskin’s right that volatility can be an issue, but there are much better ways to address it, as my colleague Liz McNichol has explained.

- The North Carolina proposal harms prospects for true tax reform. Boskin cites research suggesting that European-style consumption taxes are better for an economy than income taxes. But, that’s irrelevant, since North Carolina’s sales tax, like most other states’, is very different from a European-style consumption tax: it ignores huge swaths of consumption (such as most services) and taxes many business inputs (things that businesses buy to produce consumer goods), rather than focusing just on the consumer goods themselves.

As Boskin says, North Carolina ought to reform its sales tax, but current proposals fail to do so, and the state isn’t likely to come back for another bite at tax reform if the current tax proposals pass.

- The spending side of the equation matters. The tax proposals in North Carolina would result in much less money for education, health care, roads, and public safety, partly because the proposed income tax cut is so big. Cuts in those areas will harm the state’s economy, offsetting any potential economic benefit from income tax cuts.

The “Room for Debate” topic is, “Is North Carolina a model for state budgets?” For the above reasons plus the ones we’ve listed here, the answer is a resounding No.