BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Medicaid Is Key to Implementing Olmstead’s Community Integration Requirements for People With Disabilities

Nineteen years ago today, the Supreme Court found in Olmstead v. L.C. that states and localities must generally serve people with disabilities in the community rather than in institutions when community-based services can meet their needs. Over the last 19 years, the Olmstead decision has helped many people with disabilities live in their community rather than an institution, and Medicaid has played a key role in that. It’s the main funding source for home- and community-based services (HCBS), on which people with disabilities rely to live independently and safely in the community. Medicaid has grown better at supporting community-based services, and the President and Congress should build on that progress.

The Olmstead case was brought by Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson, two women with cognitive and mental health disabilities who were institutionalized in Georgia. They sued the state in 1996 for violating the Americans with Disabilities Act’s community integration mandate by not providing community-based services as their doctors recommended. That mandate requires that states and local governments “administer services, programs, and activities in the most integrated setting appropriate” to the needs of people with disabilities. Failing to do so in a community-based setting, the Court found, is “unjustified isolation,” and can be a form of unlawful discrimination.

Medicaid plays a key role in supporting the community integration that Olmstead requires:

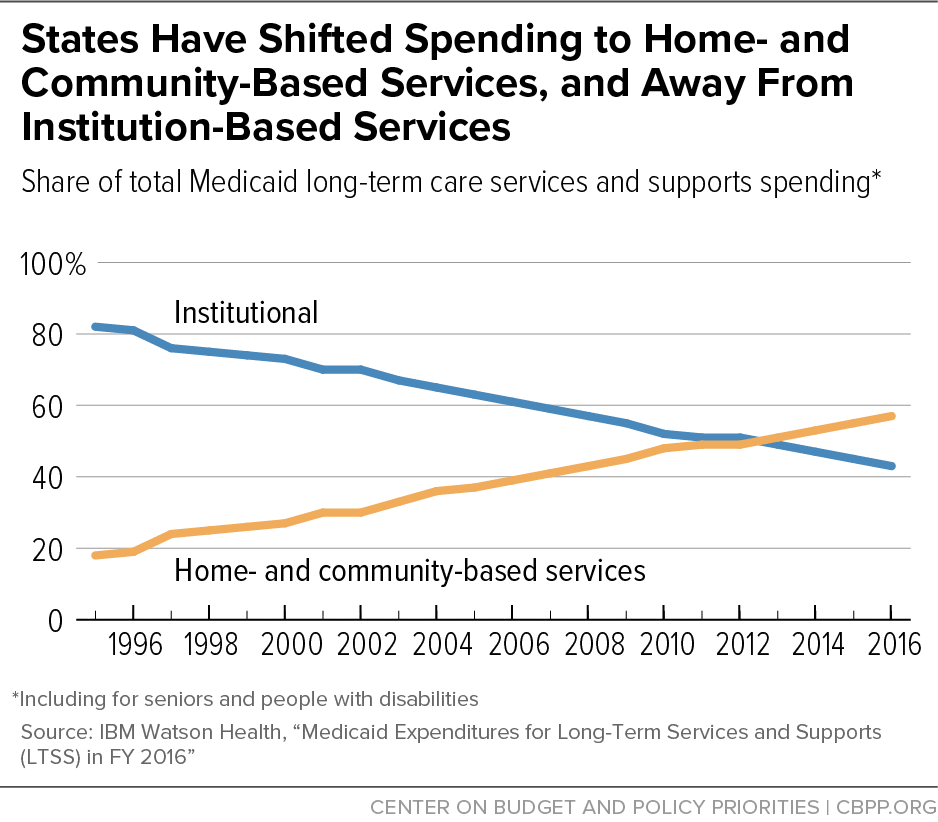

- Medicaid is the main funding source for long-term services and supports, which are increasingly home- and community-based. Medicaid long-term services and supports spending has increasingly shifted away from institutional services, such as nursing facility care, and toward HCBS, such as personal care and home health aides and services. Since 2013, Medicaid has spent more on HCBS than on institutional care, rising an average two percentage points per year (see graph). In fiscal year 2016, Medicaid spent $167 billion on long-term services and supports, with 57 percent of that total ($95 billion) for HCBS.

- Medicaid helps provide services in the most integrated community setting. In addition to home-based care, Medicaid-funded HCBS lets states offer an array of community-based mental health services and supportive employment services to various target populations. For example, states can support people with disabilities who are working by offering supported employment services, basic life and social skills training, and peer support and counseling. And the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded state options to provide HCBS to specific populations, such as individuals with mental illness.

Medicaid also promotes community integration for people experiencing homelessness. Specifically, Medicaid funds housing stability services to improve physical and behavioral health outcomes for people experiencing homelessness and at risk of institutionalization, or living unnecessarily in institutional care. People who have long histories of institutionalization or homelessness often need special supports — such as help finding safe, accessible, affordable housing, or community social services — to manage their health and living on their own. States, recently including Washington and Illinois, are increasingly adding these services to their Medicaid programs.

- Medicaid helps people with disabilities transition from institutions to the community. States can also receive enhanced Medicaid funding to expand HCBS and state efforts to transition people with disabilities from institutional to community-based settings. For example, the ACA established two new Medicaid authorities to further community integration. One gives states a higher Medicaid funding match for personal attendant services and lets them help beneficiaries cover the costs of transitioning to the community, such as by helping cover the first month’s rent and utilities or paying for bedding and basic kitchen supplies. The other authorized grants to states to make structural reforms in their long-term care systems, letting them serve more people in community-based settings.

Despite these many successes, the President and Congress can do more to ensure continued improvements in transitional care. For example, they should reauthorize the Money Follows the Person Demonstration project — which expired in September 30, 2016, and which helped over 75,000 Medicaid beneficiaries in 44 states transition back to their communities. Demonstration participants saved Medicare and Medicaid up to $978 million during their first year after transitioning to home- and community-based care.