BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Married Couples With Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services Could Lose Critical Protections

Some seniors and people with disabilities receiving home- and community-based services (HCBS) again face the possibility of losing their Medicaid eligibility and having to enter nursing homes to get needed care, because a three-month extension of “spousal impoverishment” protections expires on March 31.

Before 1988, married couples often faced significant hardship when one spouse needed care in a nursing home and the other spouse remained at home. The spouse at home could be left without enough funds to meet her living expenses because a large share of the couple’s income and assets had to go towards the costs of nursing home care before Medicaid kicked in to help pay.

Spousal impoverishment protections that policymakers enacted in 1988 changed Medicaid eligibility for married couples to let the spouse at home keep a share of the couple’s income and assets to meet her needs when the state determines eligibility and when it decides how much the couple can pay toward nursing home care. States can also apply spousal impoverishment protections to some married couples when one or both spouses receive HCBS, but this state option only applies to one of the multiple pathways that states can use to provide Medicaid HCBS to seniors and people with disabilities.

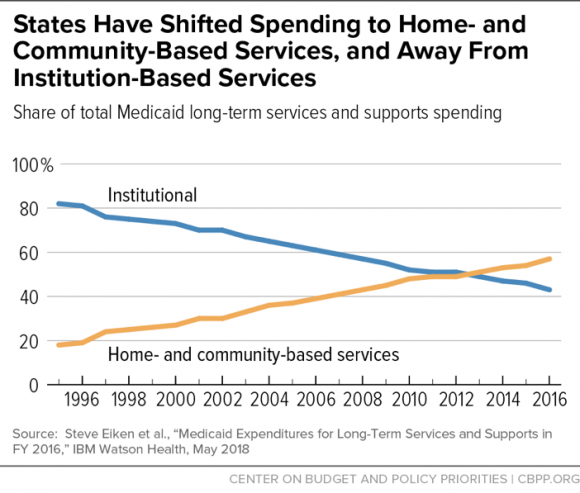

States have made dramatic progress in shifting the delivery of long-term services and supports (LTSS) out of institutions and into the community, addressing what had been an institutional bias in Medicaid. The share of Medicaid spending on LTSS spending for HCBS rose from 18 percent in 1995 to 57 percent in 2016 (see chart). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) supported the shift to HCBS by requiring states to extend spousal impoverishment protections to all married couples receiving HCBS, regardless of their eligibility pathway, for a five-year period that expired on December 31, 2018. The ACA also created new options for states to provide HCBS, which are covered by the spousal impoverishment protections.

The President and Congress extended the ACA requirement in January, through March 31, 2019. Without a further extension, some married couples could lose Medicaid eligibility because states would have to count their income and assets that were protected under the impoverishment rules, possibly making them ineligible for coverage. Most would still be eligible if they entered a nursing home; some would likely do that, but others might forgo needed care in order to stay in the community, putting their health and financial well-being at risk.

If the ACA provision expires, most states will continue applying the spousal impoverishment rules under the pre-ACA option, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey, but many seniors and people with disabilities receive HCBS under pathways not covered by the option. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has told states they could apply for a federal section 1115 waiver to extend spousal impoverishment rules to these beneficiaries, but it would likely take months for states to submit their applications and for CMS to approve them. In the meantime, many people would likely lose eligibility and suffer harm.

Policymakers should make spousal impoverishment protections permanent to avoid further disruption and confusion for beneficiaries and increased work for states. In early February, CMS released guidance informing states that they must hold off on redetermining eligibility for married couples receiving HCBS. But the guidance warned that if the protections expired at the end of March, states then would have to conduct redeterminations and recalculations of eligibility, as they were first instructed to do in November of 2018. Another short-term extension would repeat this cycle, creating uncertainty for beneficiaries and unnecessary work for state Medicaid agencies.