BEYOND THE NUMBERS

House GOP Shouldn’t Again Shortchange Working Families With “2.0” Tax Plan’s Child Credit

If, as expected, House Republicans vote later this month on their “2.0” tax-cut plan despite its severe flaws, they should fix the glaring shortcomings in its Child Tax Credit (CTC) provision. But there has been no indication that House GOP leaders intend to do so.

Nor would improving the CTC provision do enough to address the overall plan’s flaws. As explained here, the 2.0 plan would double down on the 2017 tax law’s deficiencies — by delivering substantially more to high-income households than to those with low and moderate incomes, adding considerably to the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges, and expanding opportunities for wealthy filers to avoid taxes. Rather than adopting this legislation, policymakers should restructure the 2017 law to help address the decades-long stagnation of working-class wages, and to make progress in addressing the nation’s fiscal challenges rather than making them worse.

The 2.0 plan is expected to extend the 2017 law’s Child Tax Credit provision, which raised the credit’s maximum value from $1,000 to $2,000 per eligible child under age 17 but denied that full increase to 26 million children in low- and moderate-income working families. Instead of extending this provision as is, House Republicans should fix this basic flaw. One way that they could start is by adopting a proposal advanced by Republican Senators Marco Rubio and Mike Lee during the 2017 tax debate, which would at least provide a more adequate credit to the 26 million children whose families aren’t receiving the full credit increase.

Under the 2017 law’s CTC provisions:

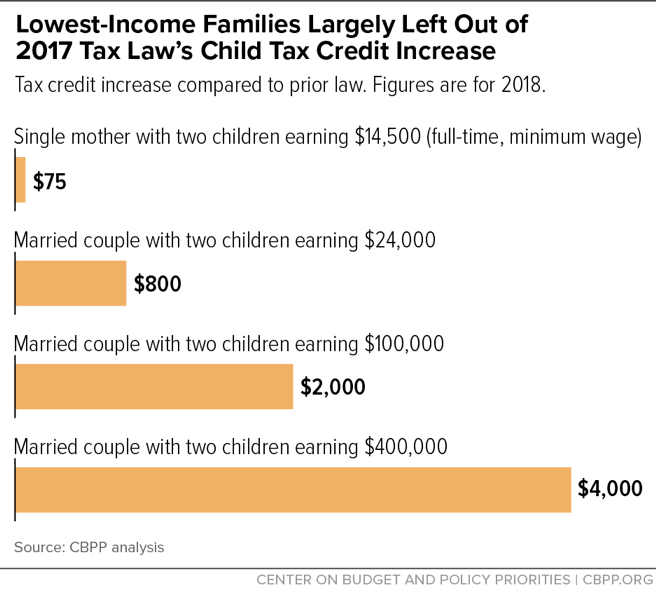

- Low-income working families that include 11 million children receive only a token CTC increase of $75 or less. Among those receiving this token amount are a single mother with two children who works full time at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour and makes roughly $14,500 a year as a home health aide helping senior citizens bathe, dress, eat, and shop for groceries. Under pre-2017 law, this mother’s CTC was limited to 15 percent of her earnings above $3,000 a year. The 2017 law lowered this threshold slightly to $2,500, giving the single mother an additional $75 (since her CTC now equals 15 percent of her earnings above $2,500, rather than 15 percent of her earnings above $3,000). The Rubio-Lee proposal, by contrast, would have eliminated this threshold so that all earnings qualified toward the credit, which would give this mother and her family an additional $450, rather than an additional $75.

- An additional 15 million children in modest-income working families also don’t receive the full CTC increase. Under the law before last year’s tax cut, the maximum CTC (which was then $1,000 per child) was the same for moderate- and middle-income families; if a moderate-income parent had enough earnings, he or she could receive the $1,000-per-child CTC just like a middle-class family could. But the 2017 law changed that, by capping the refundable CTC (the amount of the credit available to working families that don’t earn enough to owe much or any federal income tax). The law capped the refundable CTC at $1,400 per child; as a result, 15 million children in moderate-income working families are not receiving the full $1,000-per-child increase that the 2017 law has been touted as delivering.

Consider two married couples, in both of which one spouse earns money outside the home while the other does unpaid work in the home caring for two young children. In one couple, the earning spouse is a cook at a local diner making $24,000 a year. In the other couple, the earning spouse is a corporate lawyer making $400,000 a year. Under the 2017 law, the cook’s family gets a CTC increase of $800, or $400 per child, well below the law’s increase of $1,000 per child in the CTC. The lawyer’s family, meanwhile, gets a $4,000 larger CTC than under prior law: not only does it benefit in full from the increase of $1,000 per child in the maximum CTC, but the 2017 law also made it eligible for the CTC for the first time. That’s because the 2017 law more than tripled — from $110,000 to $400,000 — the income level at which the child credit begins to phase out for married couples with substantial incomes.

The Rubio-Lee proposal would have eliminated the cap that denies the full CTC increase to these millions of hard-working families. Doing so wouldn’t come close to fixing the overall problems with the 2.0 plan and would fall short of making the full set of CTC improvements needed for the poorest young children. But it would at least represent a first step toward addressing one of the underlying problems with the 2017 tax law, namely that it largely ignored the needs of low- and modest-income working families.

Working-class, non-college graduates of all races have faced four decades of wage stagnation, with low-wage workers being particularly hard hit, including millions of home health aides, cooks, child care providers, cashiers, office cleaners, landscapers, and others who work hard and on whom middle- and higher-income people depend every day. Like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the CTC is well designed to help offset this wage stagnation trend. Denying the full CTC increase to these parents and directing it to high earners instead is skewed, and seriously flawed, policy.

Furthermore, rigorous research shows that the added income that flows from policies like the CTC and EITC improves the health, educational outcomes, and future prospects of children in low-income families. That’s reason enough to provide a more adequate CTC to millions of these children.