BEYOND THE NUMBERS

High-Income People Who Received Large Net Tax Cuts in 2017 Law Don’t Need a New SALT Tax Cut

The House is poised to consider a new tax bill that would raise the cap on deductions for state and local taxes (SALT), giving another large tax cut to the same group of rich people who benefitted the most as a share of their incomes from the 2017 tax law. Over half of the benefits would go to those in the 95th to 99th percentiles for income — the biggest winners of the 2017 tax law — according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). This group doesn’t need another tax cut, and policymakers should reject the bill.

The House Republican bill would raise the SALT cap in 2023 from the current $10,000 to $20,000 for married couples with incomes under $500,000. While that ceiling would keep the tax cut from going to the top 1 percent of households, the bill would deliver another windfall to an already affluent group.

Both nationally and in affluent states, such as in the Northeast, the 2017 tax law delivered the largest average tax cut — measured as a percentage of their pre-tax income — to those in the 95th to 99th percentile, according to ITEP. Their tax cut from the 2017 law amounts to 3.5 percent of their pre-tax income, on average. No other less-affluent income group received a tax cut of more than 2 percent of their pre-tax income, while people in the top 1 percent received a 2.7 percent tax cut.

This SALT bill would double down on tax cuts for high-income households. Over half (57 percent) of the SALT tax cut would flow to those in the 95th to 99th percentile, people with incomes between $311,800 and $788,100, ITEP finds. In contrast, the bottom 80 percent of people would receive just a tiny share — 3 percent — of the tax cut. The Tax Foundation produced similar estimates, finding that over half (56 percent) of the overall tax cut would flow to people with incomes between $250,000 and $500,000, while those with incomes below $100,000 would receive only 1.3 percent of the benefits.

Policymakers and many tax filers affected by the cap on the SALT deduction may mistakenly assume that affected filers fared poorly under the 2017 law. But the SALT cap was only one component of a law with many interrelated and often offsetting provisions. Namely, two key provisions of the law gave this group of already high-income people large tax cuts, leading to large net tax cuts, even after taking account of the SALT cap.

First, the law lowered income tax rates across many of the seven tax brackets. Second, and more importantly, the law substantially scaled back the individual alternative minimum tax (AMT), which is a parallel tax system designed to ensure that higher-income people who take large deductions pay at least a minimum level of tax.

The AMT changes particularly favored the 95th to 99th percentile of households, effectively eliminating the AMT for them. The AMT changes affected households in the top 1 percent much less, in part because many of those households receive a large share of their incomes from capital gains and dividends, which face the same low tax rates under the AMT as in the underlying income tax. But for many households in the 95th to 99th percentile, the AMT tax cut plus the impact of the cuts in income tax rates were far larger than any impact of the SALT cap.

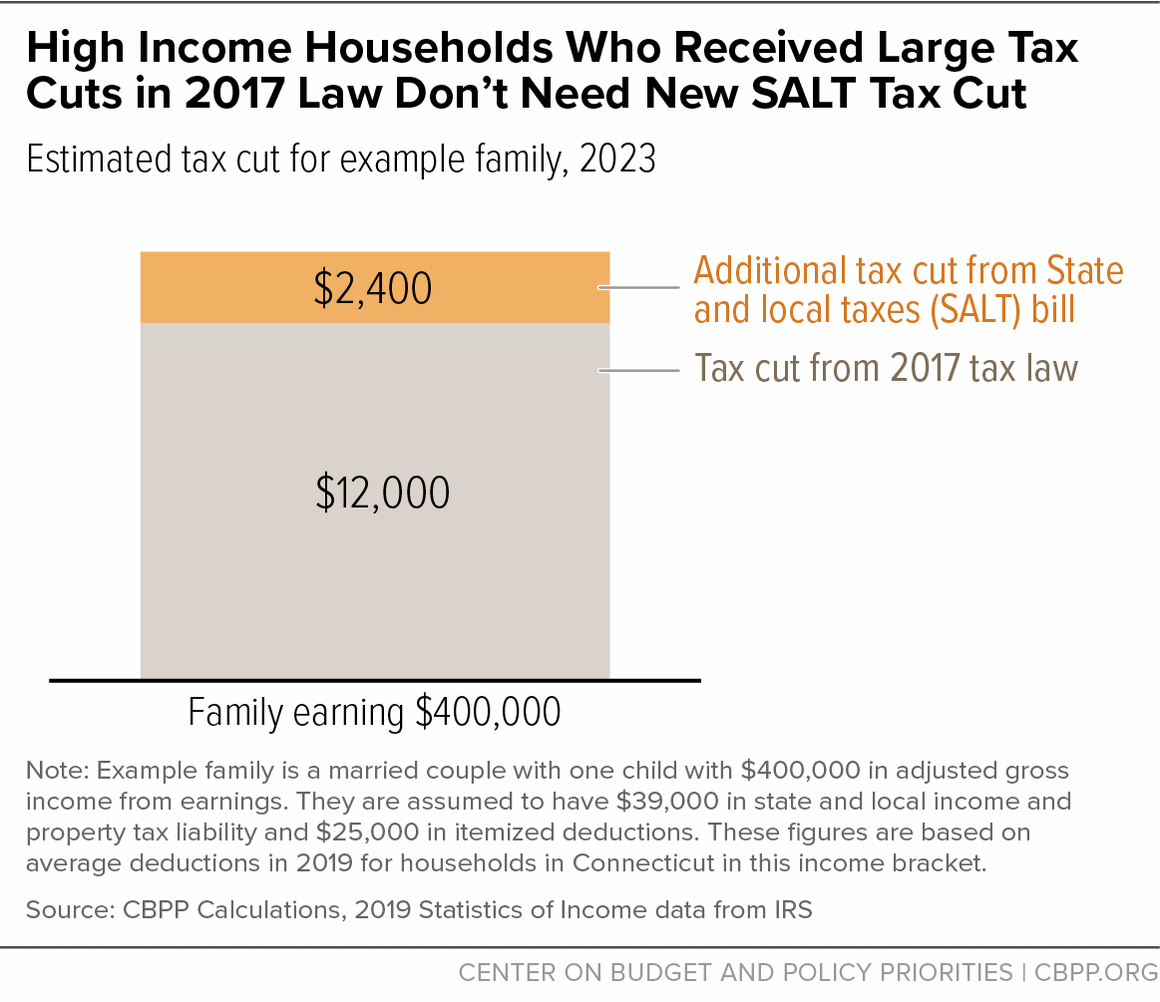

Let’s take an example, using figures based on IRS data:

Consider a married couple with one child, living in an affluent suburb of a northeastern state, with a household income of $400,000. They have fairly typical costs for their incomes and location, such as paying $27,000 in state and local income taxes, $12,000 in property taxes, and $17,000 in mortgage interest, and contributing $8,000 a year to charitable organizations. The 2017 law cuts their 2023 taxes, even after including the effect of the SALT cap, by roughly $12,000.

The new House Republican bill would give this family — whose incomes put them in the top 5 percent in the country — an additional tax cut of roughly $2,400, bringing their combined tax cut from the 2017 tax cuts and this bill to over $14,000.

The new House Republican SALT bill would cost $8 billion for the year it is in effect, ITEP estimates. The Tax Foundation similarly estimates that it would cost $11.7 billion. An estimate from the Joint Committee on Taxation — the congressional entity that evaluates the cost of tax legislation — hasn’t been released yet.

In stark contrast to the House-passed bipartisan bill expanding the Child Tax Credit along with business tax provisions, which is offset by ending a fraud-laden business tax credit, the SALT bill includes no offset. This is particularly glaring because policymakers could do so by closing a loophole that lets owners of pass-through businesses, including partnerships and S corporations, effectively bypass the SALT cap.

Since the 2017 law, many states have enacted laws allowing certain business owners — known as “pass-through” businesses — to convert their personal income taxes, which are subject to the SALT cap, into business taxes, which aren’t subject to it. This loophole costs around $20 billion per year, according to the Tax Policy Center, and primarily benefits high-income owners of pass-through businesses, like law firm partners and investment fund owners.

This bill should have been offset by closing this loophole, but regardless, there is no reason to give an additional tax cut to a group of well-off people who received the largest tax cuts (as a share of their income) from the 2017 tax law — a law that was skewed to the rich, cost significant federal revenue, and failed to deliver on its economic promises. Policymakers should reject this bill.