BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As Tax Day Approaches, These Charts Show Why the New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed

With Americans focusing on taxes as the April 17 deadline approaches, these charts show why the tax law enacted in December needs wholesale restructuring: it will increase inequality, reduce revenues at a time when the nation needs to increase them, and invite rampant tax avoidance. As our major new report details, the new law:

1. Ignores the stagnation of working-class wages and exacerbates inequality.

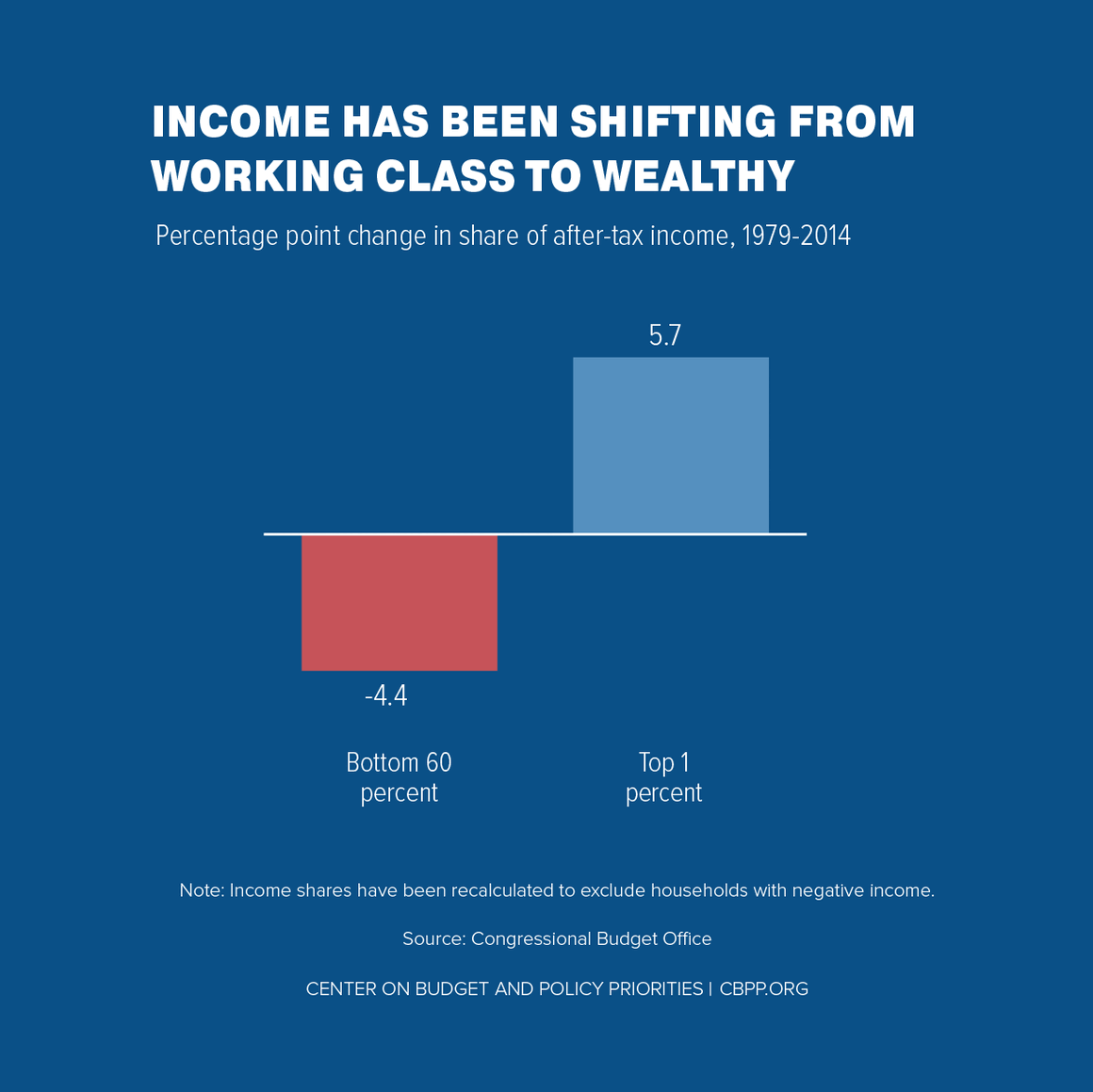

Income has shifted from the bottom and middle to the top in recent decades, as wages have been close to stagnant for working families while rising dramatically for those at the top. The share of income flowing to the bottom 60 percent of households fell by 4.4 percentage points between 1979 and 2013, while the share flowing to the top 1 percent rose by 5.7 percentage points (see chart 1).

The economic environment has been particularly challenging for working-class households, defined here as those with working-age adults in which no one has a college degree. The after-tax income of a typical working-class family of three would be about $9,600 higher ($58,300 instead of $48,700) if its income had grown at the same rate since 1979 as a typical household with a college degree.

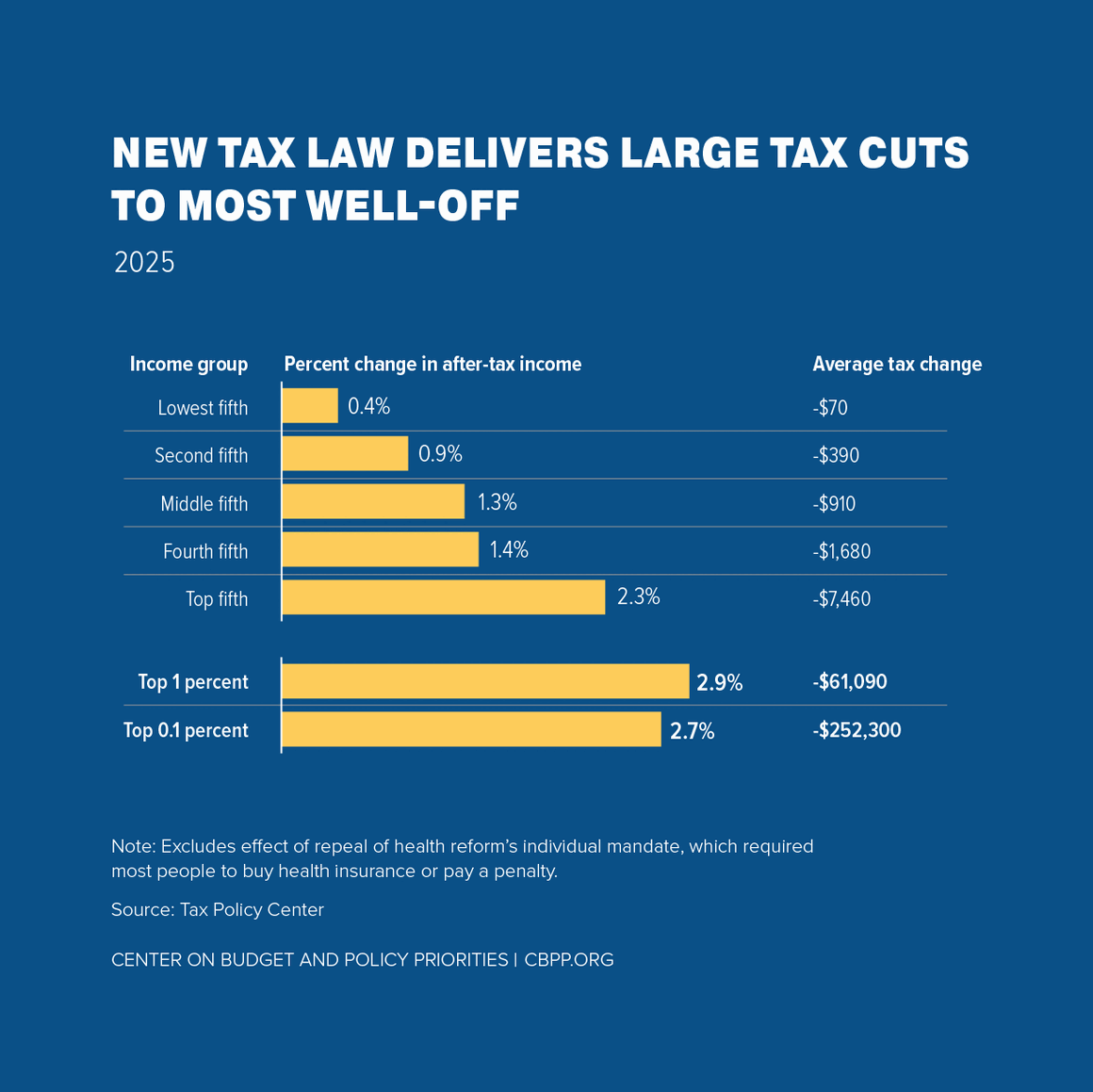

Instead of pushing against this trend, the new tax law exacerbates it. In 2025 the top 1 percent of households will receive tax cuts averaging $61,100, and the top 0.1 percent will receive windfalls averaging $252,300. In stark contrast, the bottom 60 percent of households — those making under $91,700 — will receive about $400, on average. Measured as a share of income, the tax cuts will be roughly three times bigger for the top 1 percent of households than for the bottom 60 percent, according to the Tax Policy Center (TPC). (See chart 2.)

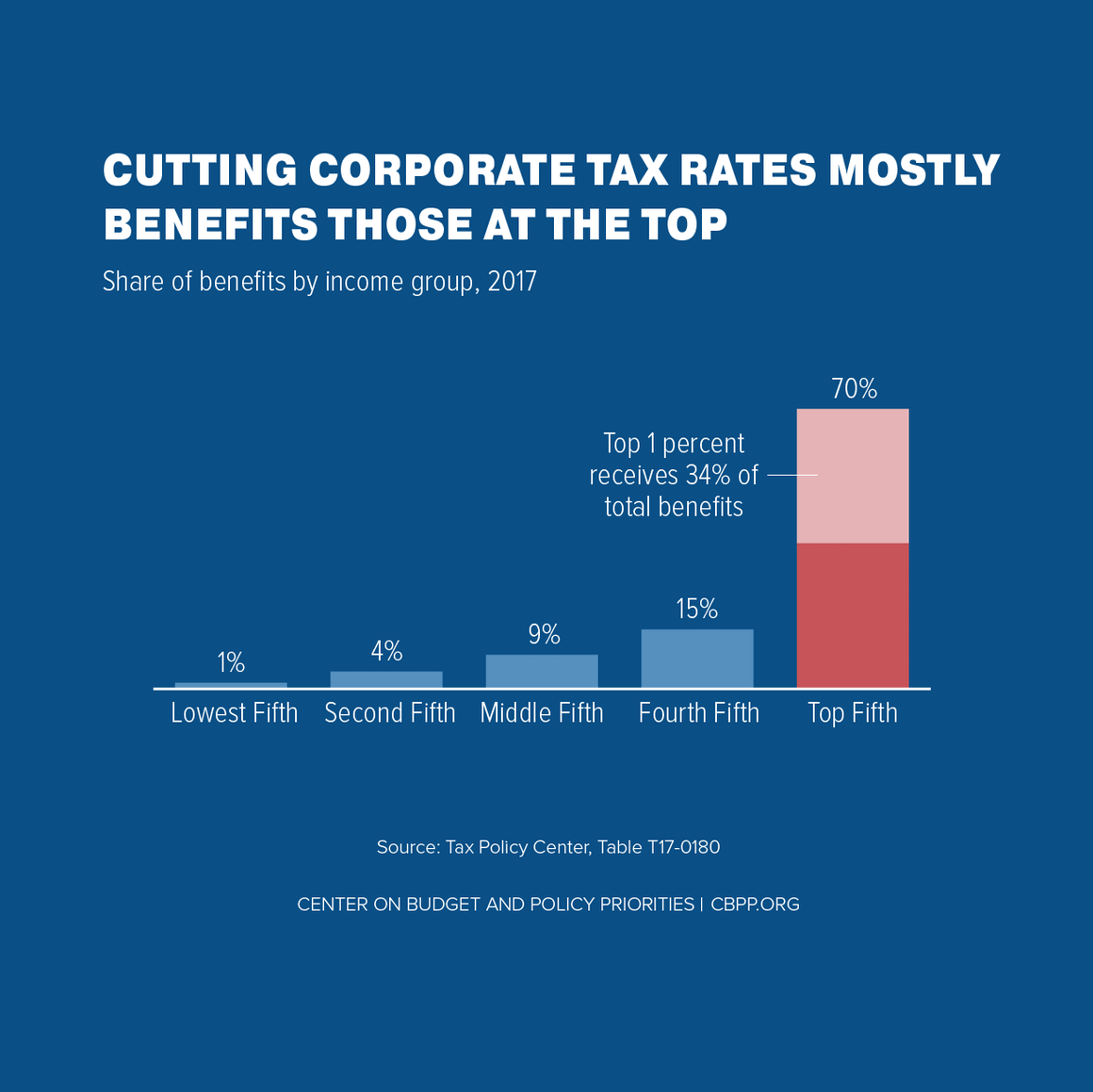

The centerpiece of the new tax law, a cut in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, contributes to the law’s upward tilt, as it largely benefits corporate shareholders. TPC estimates that 34 percent of the benefits from cutting corporate tax rates ultimately flow to the top 1 percent of households. (See chart 3.)

Other key parts of the new law also are heavily tilted to the wealthy, such as the new 20 percent deduction for “pass-through” income — the income that owners of partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships report on their individual tax returns — (see below) and the doubling of the estate tax exemption, which enables the wealthiest households to pass on $22 million in assets per couple tax-free to their heirs.

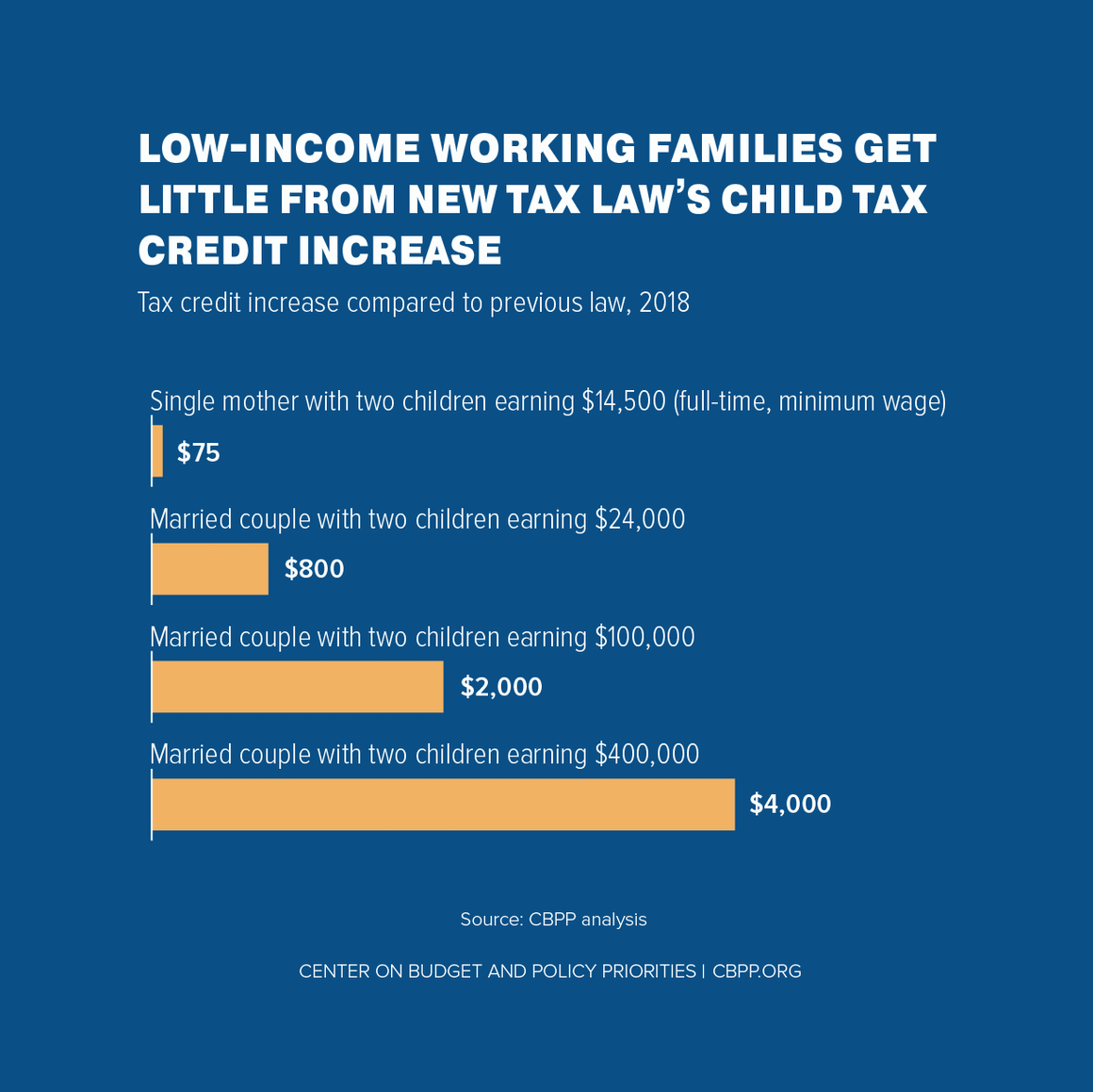

Working-class families are largely an afterthought in the new law. In making last-minute changes to the bill, lawmakers lowered its top individual tax rate but rejected the effort by Senators Marco Rubio and Mike Lee to provide more than a token increase in the Child Tax Credit (CTC) for children in low-income working families. (See chart 4.) While Rubio and Lee secured a more adequate CTC increase for moderate-income families, 10 million children under age 17 in low-income working families will receive no CTC increase or a token increase of $75 or less. Another 14 million children will get a CTC increase of more than $75 but less than the full $1,000-per-child increase that families with higher incomes will receive.

2. Weakens revenues at a time when the nation will need to raise more revenue.

The new tax law will cost $1.5 trillion over the next decade, the Joint Tax Committee (JCT) estimates. These large revenue losses are irresponsible given the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges.

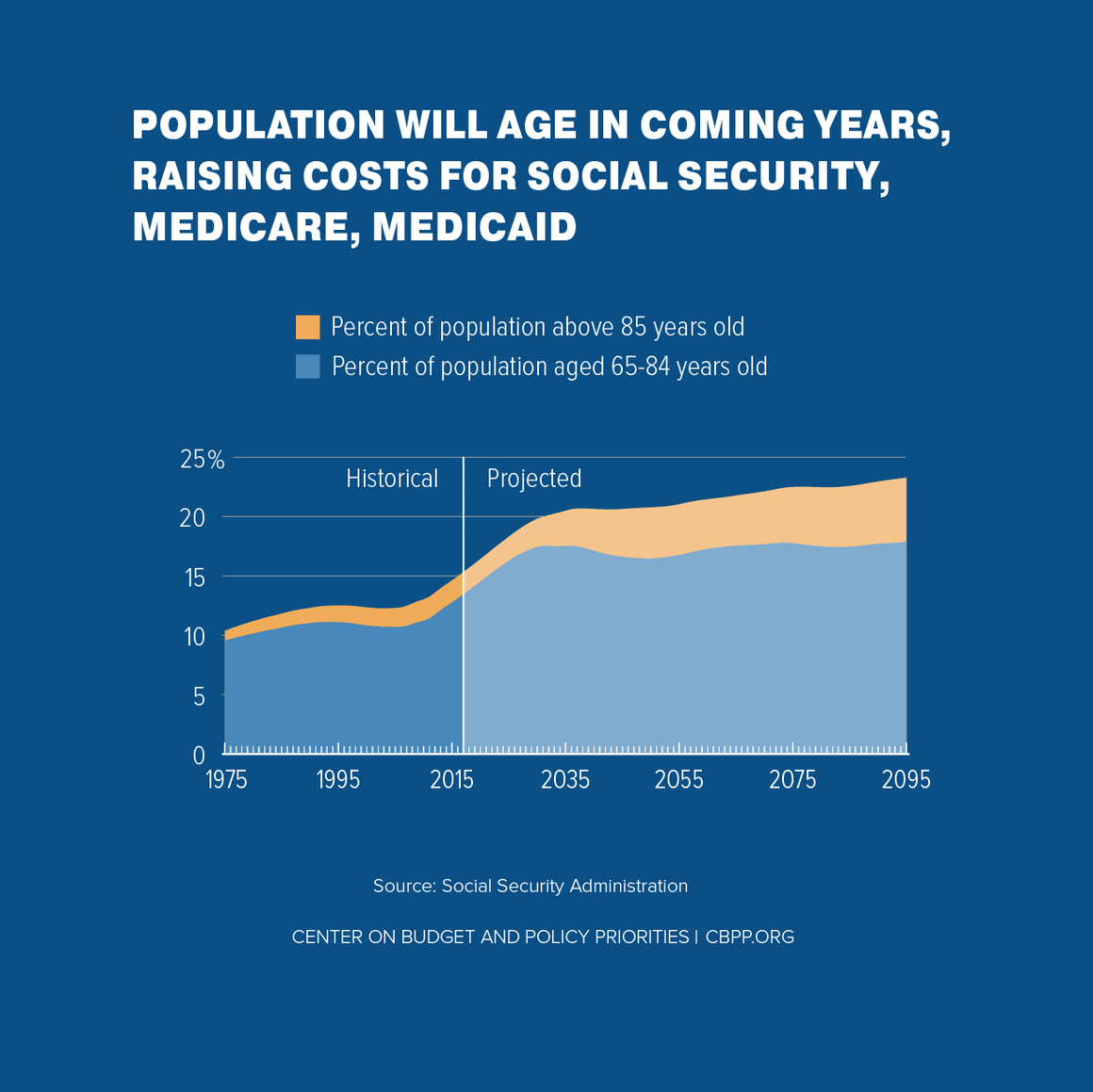

Federal spending will need to rise as a share of gross domestic product over the next few decades due to several factors, most importantly the aging of the population. The oldest baby boomer today is 72 years old and the youngest is 54, so the shares of the population above 65 and above 85 will rise sharply. (See chart 5.) This will significantly increase the budgets of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. Moreover, health care spending — in both the public and private sectors — has long grown faster than the economy and will likely continue doing so, in part due to new procedures, drugs, and treatments that improve health and save lives but also add to costs.

The bottom line is that the revenue path the new tax law sets is simply unsustainable.

3. Invites rampant tax gaming and risks undermining the integrity of tax code.

True tax reform would simplify the tax code and narrow the gaps between how different types of income are taxed so that individuals and businesses base their economic decisions on economics, not taxes. The new law does the opposite, adding complexity to the tax code and introducing new, arbitrary distinctions between different kinds of income.

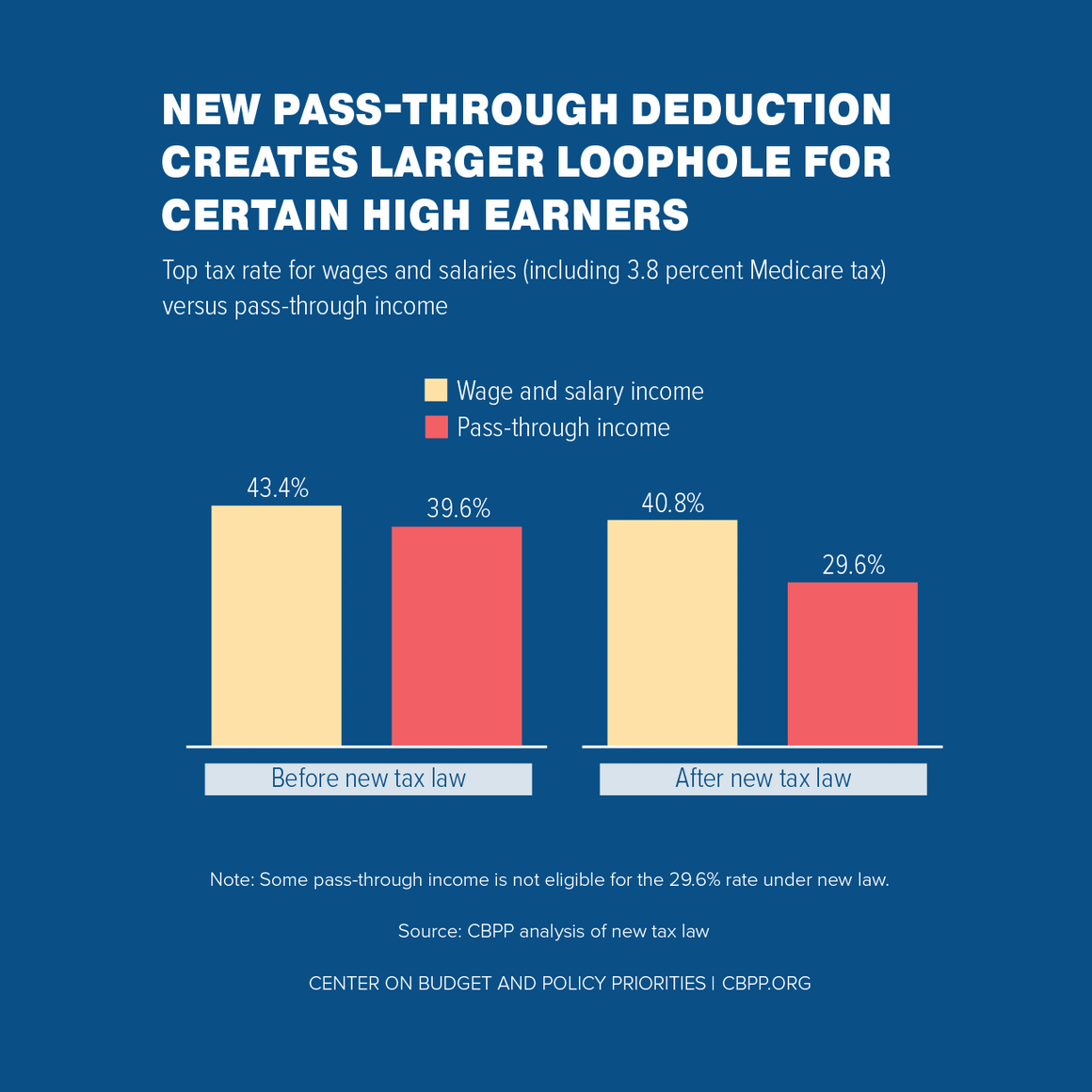

A prime example is the deduction for most forms of pass-through income, as described above. The deduction effectively means that certain pass-through income will face a lower tax rate than wages and salaries, which creates an incentive for high-income individuals to reclassify their salaries as pass-through income. (See chart 6.) While the new law includes complex “guardrails” intended to prevent that abuse, they are poorly designed.

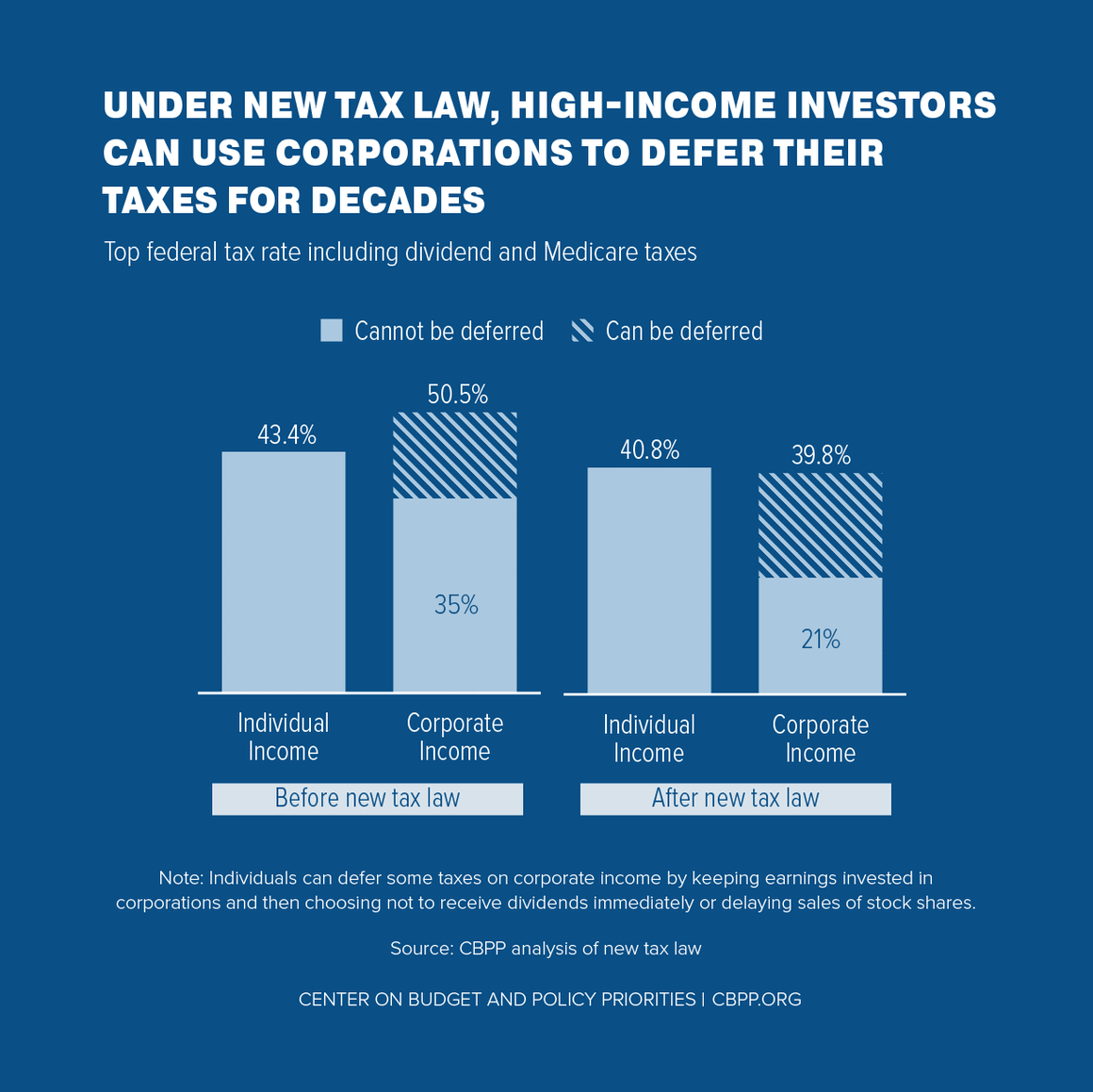

The new law also creates a powerful incentive for wealthy Americans to shelter large amounts of income in corporations by slashing the corporate rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, thereby opening up a wide gap between the top individual tax rate and the corporate rate. An investor with a multi-million-dollar bond portfolio can now place it in a corporation and pay roughly half the tax rate on the interest income that she would pay if she faced the individual tax rates. She might have to pay taxes on dividends or capital gains on the wealth that accrued in the corporation, but she could defer that second layer of tax for decades and even avoid it altogether by passing the corporation that houses her bond portfolio on to her heirs. (See chart 7.)

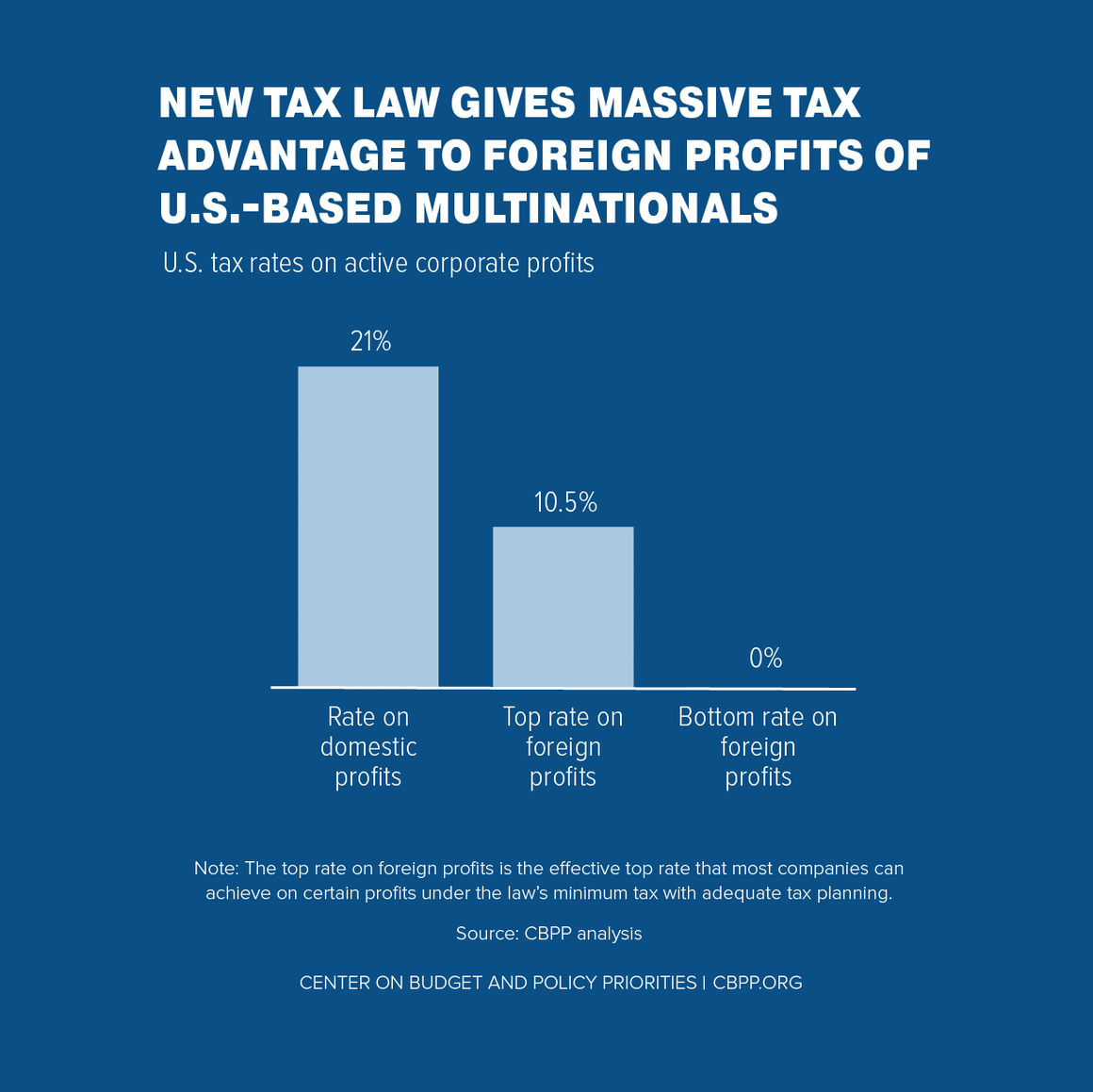

Also, the new law moves U.S international tax rules to a “territorial” system, which largely exempts corporations’ foreign profits from U.S. tax and thereby creates an incentive for multinationals to shift profits and operations overseas. The drafters of the law put in place a minimum tax to limit this incentive, but it is seriously flawed; for example, income subject to the minimum tax is taxed at a 10.5 percent rate, half the rate on domestic corporate profits. (See chart 8.) And the minimum tax may in fact add to incentives to shift both paper profits and real investments and operations overseas since the more such assets are held abroad, the more foreign income a company can shield from the minimum tax.