BEYOND THE NUMBERS

With President Trump and Congress boosting overall non-defense discretionary funding for 2018 and 2019, they now must use some of these funds for the fast-approaching 2020 census. The President’s latest request for 2018 funding for the census moves in the right direction but remains below what outside experts believe is needed to ensure an accurate census count, and it omits funds for contingencies that Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has recommended. The President's 2019 request also falls well below what the Commerce Department projects is needed.

The decennial census count, mandated in the Constitution, supports our electoral system and much public- and private-sector decision-making. The 300-million-plus Americans must be counted accurately to ensure that each state has fair representation in Congress, enable fair redistricting within states, and guide the allocation of federal funding for programs from Medicaid to economic development and child care. Moreover, the census forms the statistical foundation for many annual and monthly surveys, including crucial surveys on unemployment, education, health, and commuting. Businesses use this information to understand markets and plan their locations, and governments use it to plan everything from locating schools and roads to funding disaster relief and setting interest rates.

Yet funding problems over the last several years — due in part to tight annual caps on overall non-defense discretionary funding — have hamstrung census preparations. Low and delayed funding forced the Census Bureau to cancel key field tests in 2017 and 2018 and slowed progress on basic communications and outreach strategies to encourage the public to fill out the census.

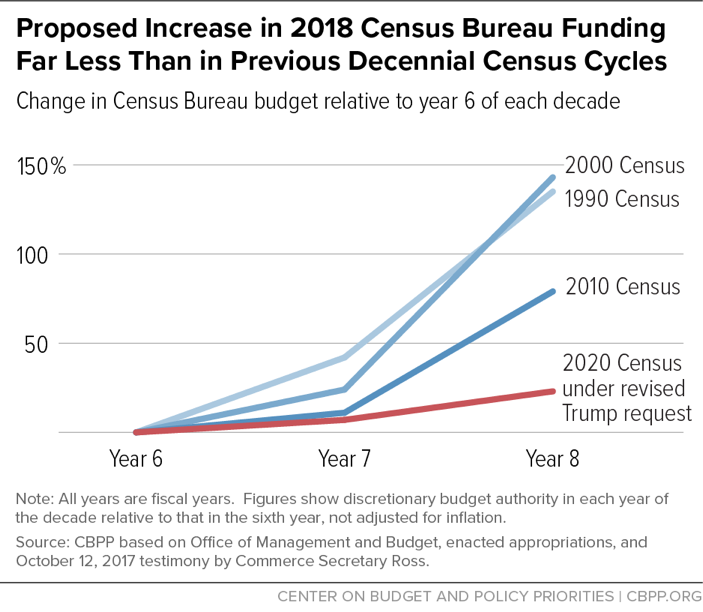

To ensure a successful census, final Census Bureau 2018 funding should be well above what the House ($1.507 billion) and Senate appropriators ($1.521 billion) approved earlier this year. The President, who originally requested slightly less than those amounts, subsequently increased his official request by $187 million to $1.684 billion. Even this higher level, however, represents just a 23 percent increase over 2016 funding. At this point in the decennial census cycle — just two years before the census is conducted, when critical field preparations and a final “dress rehearsal” must be completed — funding should be ramping up significantly more. The President and Congress have traditionally provided far larger increases in funding at a similar stage in past decades, including increases of 79 percent from 2006 to 2008, 143 percent from 1996 to 1998, and 135 percent from 1986 to 1988. (See figure.)

While the President’s revised request reflected a recognition that his initial request was far too low, outside experts estimate that the Census Bureau needs at least $1.848 billion for 2018 to be ready for 2020 and avoid cuts in other important areas of the bureau’s budget. That would include funding to complete planned communications work and hire 200 partnership staff to engage with local faith groups, local officials, and others who can help build trust in the census, as well as $50 million that Secretary Ross recommended last October for the first installment of a contingency fund to address natural disasters such as wildfires and other concerns.

The President’s request for 2019, $3.8 billion, is also low. It falls well short of giving the Census Bureau the strong ramp-up in funds that a December Census Bureau cost estimate said the 2020 census program would need in 2019.

The 2020 census faces particular challenges that make strong preparation even more critical. Among them is the plan to offer an online response option for the first time ever, which the Census Bureau hopes more than 2 in 5 households will use to complete the census. While that should make participating easier, improve response rates, and lower Census Bureau costs for households with online access, it will require careful system testing in advance. The online option also risks disproportionately undercounting those without Internet access. Avoiding a “digital divide” in census undercount rates will require significant outreach and follow-up to rural, low-income, and other populations that are less likely to have reliable broadband or Internet access, making the final two years of research and deployment of advertising and outreach strategies vital.

A poorly funded, poorly executed census would likely depress the overall count and leave some places and population groups more undercounted than others. The 1990 census is a case study of a relatively large undercount; 12.2 percent of American Indians on reservations were missed, the highest undercount rate for any racial group, followed by high rates for the non-black Hispanic population (5.0 percent) and black population (4.6 percent). Whites experienced far less undercounting overall, but rural white renters were also undercounted at a high rate (5.3 percent). While the 2000 and 2010 census both lowered the overall net undercount and generally narrowed the gaps between groups, underfunding for 2020 could erase these improvements — potentially leaving undercounted groups with less representation in Congress and statehouses, lower federal resources, and less attention to their needs.

In addition, policymakers must ensure that the Census Bureau doesn’t add a citizenship status question to the 2020 census. The Justice Department asked the Census Bureau in December to add such a question — an alarming, last-minute move that would likely depress immigrant participation and lead to “bad Census data,” according to four past Census Bureau directors who served in Republican and Democratic administrations.