States can expand opportunity and build stronger, more prosperous, and inclusive communities by reducing the incarceration of children and young adults and increasing the use of sensible alternatives that advance equitable outcomes. The number of youth being arrested and incarcerated has fallen dramatically over the past two decades, giving states an opportunity to close youth prisons and invest the savings into community-based approaches that nurture children and young adults while building stronger communities.[1] These policy improvements would particularly benefit communities of color since young people of color are still much more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers.

Youth justice reforms have already saved states millions of dollars and improved outcomes for young people without putting the public at risk.[2] Even as states have arrested and incarcerated fewer youth, crime rates for young people have continued to fall, and are now at historical lows.[3] And many young people in the justice system are there for low-level, technical violations.[4] Appropriate juvenile justice reforms can help a young person access the services and supports they need as they transition to adulthood. In boosting young residents’ prospects, these reforms are also enabling states to unleash their people’s full potential, setting up their economies to be stronger, and fairer, down the road.

Black and Indigenous youth are persistently incarcerated and sentenced at higher rates than white youth — a disparity that persists as overall youth detainment is declining.[5] Across the country, as of 2019, over 36,400 children — disproportionately young people of color — remain in youth facilities on any given night.[6] Often these young people come from low-income and disinvested communities where a lack of resources diminishes the opportunities to fully recover from being in confinement.

Locking up children and young adults is expensive and can cause serious harm to youth who are separated from their family and community, sometimes by hundreds of miles and with few ways to stay connected.[7] The separation, often compounded by abusive practices within the facilities, can cause lasting physical and mental health issues for these children.

States should stop placing youth in confinement and should adopt antiracist policies that make strides toward more equitable outcomes, such as reforming youth justice systems and reinvesting in solutions for young people to thrive. Though much work remains, several states have made such reforms over the last 15 years to reduce youth incarceration, including by closing youth prisons and shifting to community-based approaches.

State lawmakers can make even greater strides both in the short- and long-term to ensure youth justice and equitable outcomes for them and their communities. They can:

- Produce racial equity impact analyses for juvenile justice bills;

- Require an independent analysis of the costs and benefits of incarcerating youth versus investing more in community-based services; and

- Meet with community advocates and justice-involved children and young adults to inform youth justice reform policies.

Reducing incarceration for children and young adults and investing in community-based solutions and other investments in the communities most harmed by the justice system would help right historical wrongs, reduce inequities, and foster more widespread opportunity.

Tens of thousands of young Americans are incarcerated without being convicted or for low-level offenses. In 2017, nearly 1 in 3 young people who were incarcerated — about 13,500 — were being held for low-level offenses, non-violent offenses, and posed little risk to public safety, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.[8] Another 7,000 have not been found guilty and are awaiting trial.[9]

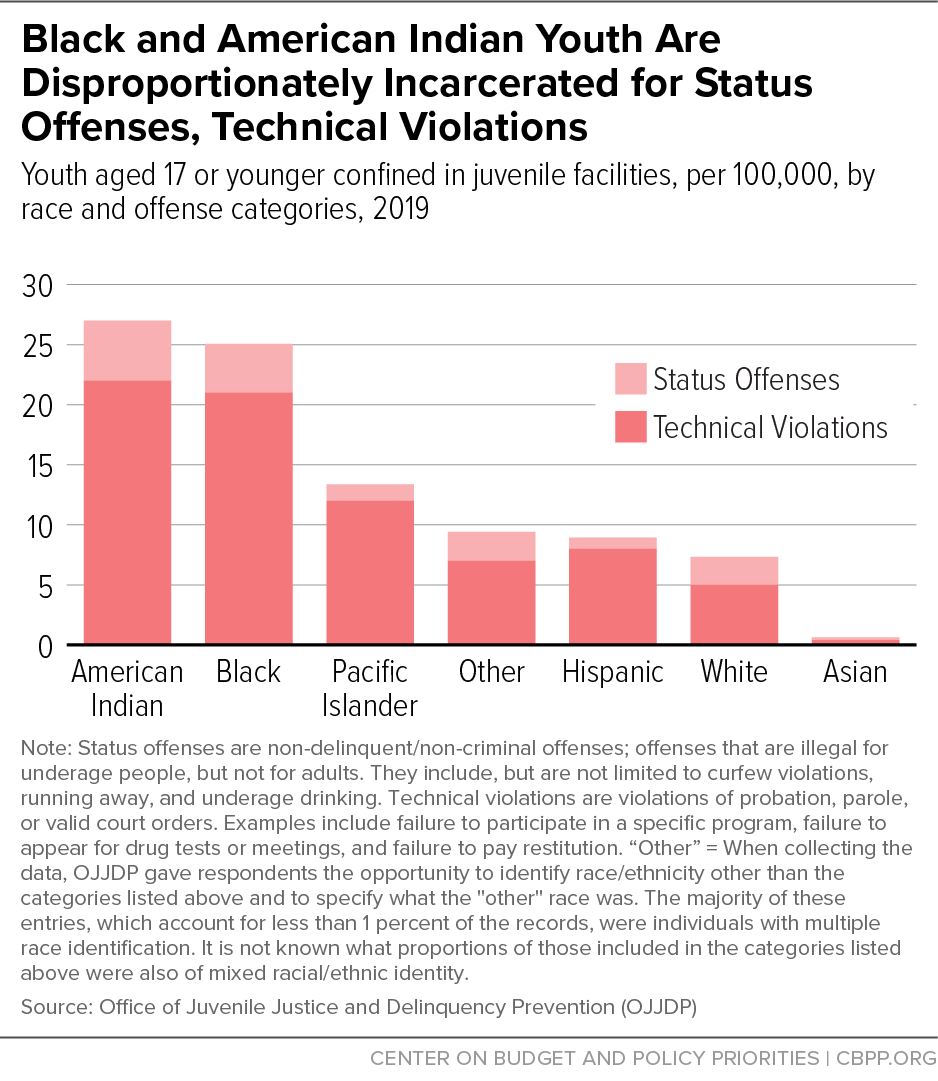

Young people of all races are harmed by these policies, but young people of color are disproportionately affected. They are overrepresented in juvenile facilities due to systemic racism, implicit bias, and related barriers to opportunity such as overly aggressive policing tactics, poorly resourced schools, and fewer community supports and employment opportunities than their white peers. (See Figure 1.) Among racial and gender groups, Black boys, Black girls, and American Indian girls, in particular, are disproportionately locked up.[10] American Indian girls are four times more likely than white girls to be incarcerated, and the rates for Black girls are nearly as high.[11]

While boys are much more likely to be locked up than girls, girls are particularly likely to be incarcerated for status offenses such as truancy, running away, or out-of-control behavior.[12] Girls comprise one-third of all youth incarcerated for status offenses, despite representing just 15 percent of the juvenile justice population.[13] As a result of poor policies and a lack of reinvestment, the share of Black girls in confinement continues to increase, and they are put in residential placements at higher rates than their white peers for low-level offenses or minor technical violations such as missing a parole officer meeting.

LGBTQ youth are more likely to be arrested, sentenced, and physically harmed while in confinement than their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers.[14] Further, incarcerated young people who identify as LGBTQ or gender non-conforming are disproportionately youth of color.[15]

These trends deepen racial inequalities and derail the futures of many young people of color, preventing them from reaching their potential and contributing more fully to their communities as adults.

Incarcerating young people costs state taxpayers across the nation billions of dollars each year while doing little to rehabilitate those who are locked up or reduce crime.[16] In fact, young people who have been incarcerated are more likely to be arrested again, and face barriers in obtaining an education and stable employment.[17] Lawmakers must prioritize closing youth prisons because the act of incapacitation is simply illegitimate to make sure youth and young adults are able to reach their fullest potential – it only constrains the resources and tools to invest in young people’s lives.

It now costs states an average of $214,620 a year to incarcerate one child in their most expensive confinement facilities, the Justice Policy Institute (JPI) estimates, a rise of 44 percent from 2014.[18] These costs don’t account for the longer-term effects of youth incarceration, which could cost taxpayers between $8 billion to $21 billion a year in the public costs of recidivism, lost future earnings and tax revenue, additional public health care spending, and the public costs of sexual assault on confined young people, JPI estimates.[19]

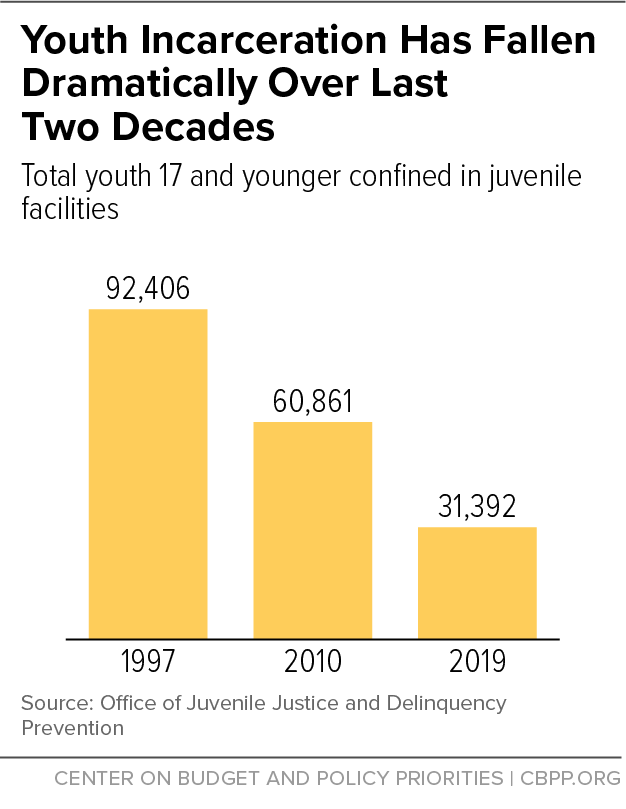

Youth incarceration has fallen dramatically over the last two decades. (See Figure 2.) In 1997, 92,406 youth were confined in state and local facilities; that dropped to 31,392 youth in 2019.[20] During roughly the same period, about half of all juvenile justice facilities closed — a drop from 3,047 facilities in 2000 to 1,510 in 2018.[21]

Nevertheless, states still devote an estimated $5 billion annually to youth prisons.[22] This is both costly and ineffective. States could achieve significant savings by continuing to close youth facilities, decreasing the number of beds for out-of-home placements for those youth so that their use is limited to extreme cases and for the shortest time possible, and reinvesting dollars from the youth justice system to community-based programs for justice-involved youth.[23]

Many youth facilities have policies and practices similar to the adult system, where youth are not allowed outside of their rooms without handcuffs or in public places without foot shackles[24] and sometimes placed in solitary confinement for days at a time or subject to physical and chemical restraints.[25] For example, youth facilities may give antipsychotic drugs often prescribed for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia to young people regardless of whether they have been diagnosed with a mental illness.[26]

Often youth experience sexual abuse by other youth, correctional officers, and other staff, which can lead to a host of mental health issues that often go unaddressed, resulting in long-term harm.[27] Research suggests that people who are sexually abused or assaulted at a young age experience years of trauma, find it hard to have interpersonal relationships, and require mental health services well into their adulthood.[28] As a result of these traumatic experiences, youth in prison are often at high risk of dying by suicide.[29]

Individuals incarcerated during adolescence are more likely to be reincarcerated in their 20s and early 30s, to develop alcohol dependency, and to need assistance to meet their everyday needs than their peers who have never been incarcerated.[30] Incarceration during adolescence and early adulthood has also been shown to have long-term adverse impacts on individuals’ health.[31] Youth who enter juvenile justice facilities often leave worse off physically and mentally, creating lasting impacts.[32]

Policy Reforms Can Reduce Incarceration, Free Up Funds for More Effective Solutions

Locking up young people is an ineffective one-size-fits-all model. Dollars currently spent on youth incarceration could be better spent on community-based alternatives, education, and work training programs that could help young people and their communities thrive. A diverse set of community- and school-based solutions to address youth justice would be more effective, research finds.[33]

Many of these alternatives are less expensive approaches that can hold a young person accountable while better addressing what the child needs to secure a brighter future through schooling, vocational training, or treatment. As states shift from an incarceration-based approach to alternatives, they should prioritize effective and efficient, culturally relevant, and responsive community-based reforms.[34] In taking this approach, states should employ a “continuum of care” model, an array of non-residential community-based programs, supports, resources, and services designed to meet the individual needs of young people and their families in their homes.[35]

For example, Black girls are more likely to be reincarcerated on technical violations or receive longer sentences for repeated offenses after they are released from youth facilities in part due to racism and because they typically have little access to community-based alternatives that are gender-appropriate in their community.[36] The compounding effect of poor policies and lack of community-based resources often means Black girls are systemically set up to fail instead of given opportunities for services that keep them in their community and out of prison. Community-based programming helps address the underlying causes for repeated offenses and helps youth stay out of youth justice facilities.

Community-based services not only help youth avoid jail and prison; they also help youth and their families and communities to thrive. Effective alternatives to incarceration can include access to mental health services, to public services for the affected youth or family, and to restorative justice services within communities.[37] For example, Youth Advocates Programs, Inc. provides wraparound services for the youth, young adults, and their families such as access to part-time employment, transportation to attend court, and assistance navigating the child welfare system.[38] These services can advance racial and ethnic equity as well by taking into account the whole person and their well-being instead of focusing only on the offense they committed, making long-term success more likely.

These services are often best administered by community-based nonprofit organizations with deep roots in the most affected communities. States and localities should work to develop close relationships with such organizations and the communities in which they work and look to them for policy advice and program development.

States should fund programs that focus on racial and gender identity and should provide adequate resources for these services so they can meet individual needs and challenges equitably. States can provide funding to create community-led and based programs and support groups that are already providing these services to children and young adults. Community-based programs should be culturally responsive to the needs of the youth and their community, conscious of the racial history of juvenile policies, and understand the existing relationships between communities of color and the criminal justice system. Advocates should, when available, share common identities with young people: they live in the same neighborhoods, speak the same language, and may share race, ethnicity and interests. States should encourage programs that take a thoughtful and responsive approach to gender issues, since gender plays a key role in shaping the experiences of youth with the criminal legal system.[39]

Policymakers taking this approach would ideally increase the total amount of funds devoted to relevant programs and departments, but states and localities also have the option to redirect existing spending at the department or agency level, specifically to shift dollars away from locking up youth and into community-based approaches. For instance, after North Carolina enacted criminal justice reforms in 2011, policymakers shifted $16 million into community-based treatments by drawing on resources that were already in the Department of Public Safety’s budget but would no longer be needed for corrections costs. One drawback to this approach is that reinvestment may only occur within the formal justice system. Other important investments in education, employment services, and health care may go unfunded because they are not under the purview of state juvenile justice or correction systems.

Several states have already adopted reforms to reduce youth incarceration, including closing youth prisons and shifting to community-based approaches.

- In 2013, in an effort to reform the youth and criminal justice system, Georgia enacted a series of policies estimated to save the state $85 million over five years and reduce recidivism.[40] House Bill 242 created a grant program in four counties that reduced the number of committed youth, shifted $30 million to community-based alternatives, and closed several juvenile facilities.[41]

- Through its Redeploy program, Illinois gives resources to counties to implement community-based programming for youth who would otherwise be placed in state-run facilities. An oversight board monitors and evaluates the program, and counties that receive program funds must reduce the number of youth incarcerated by 25 percent relative to the previous three years, or pay a penalty to the state.

- In 2018, Tennessee committed $4.5 million per year to expand community-based services and provide juvenile justice courts with more treatment options, particularly targeting low-income and rural areas in the state. The Juvenile Justice Reform Act includes policy recommendations that are aimed at reducing the number of youth being incarcerated and reinvest money into community-based services as primary alternatives for low-level and non-violent offenses.[42]

- Under Wisconsin’s Youth Aids program, the state incentivizes community-based alternatives to incarceration by charging counties for most of the cost of each youth placed in state correctional facilities, and provides funding for each county to pay for community-based programming and services for justice-involved youth.[43]

Three states in particular have shown how smart juvenile justice reforms can reduce incarceration and expand opportunity, without additional risks to public safety.

Reforms to youth confinement in Connecticut over the last 15 years have dramatically reduced the number of young people the state locks up. In 2005, state lawmakers approved a bill prohibiting youth detention for violating court orders in cases arising from a status offense such as truancy, running away, or out-of-control behavior. Additional legislation enacted in 2007 called for non-judicial handling of virtually all status offense cases and authorized a new network of support centers that provide targeted services for such youth including screening and assessment, crisis intervention, family mediation, mental health treatment, and educational options.[44] As a result, the number of youth detained for status offenses dropped from 493 in 2006-07 to zero in 2008-09, and the share of status offense referrals processed in court fell from 50 percent of all referrals filed in 2006 to 4.5 percent in 2010 and 2011.[45] The state also raised the age to 18 to charge an adult for a crime, which resulted in 16- and 17-year-old people leaving adult prisons.[46]

Additional reforms followed. In 2016, Connecticut eliminated the use of pretrial detention for cases where the court deemed that a child was a risk to themselves or in an unsafe environment.[47] In 2017, lawmakers removed minor status offenses from the court system entirely, instead diverting affected youth to holistic community programs. State policymakers also closed the last two secure facilities for juveniles: the Pueblo Unit (for girls, closed in 2016) and the Connecticut Juvenile Training School (for boys, closed in 2018).[48]

Such policy and practice changes contributed to significant reductions in the state’s court docket of minor criminal or vehicle offenses committed by young people; these cases were nearly 30 percent lower over the course of the state’s 2018 budget year than over the same timespan a decade earlier.[49]

Despite such reforms, juvenile detentions remained disproportionately high among youth of color, falling more sharply for white youth than their Black and brown peers. Referrals to juvenile court fell by 30 percent for white youth from 2015 to 2019, versus 25 percent for Black youth and only 16.5 percent for Hispanic youth. And, in 2019, Connecticut admitted 465 Black youth and 432 Hispanic youth to its juvenile detention facilities, compared to only 177 white youth.[50]

Although the state has saved money from its efforts to reduce incarceration, policymakers have underinvested in constructive alternatives. In 2016, for example, prior to closing the Juvenile Training School, the Department of Children and Families saved $20.6 million by downsizing staffing at the facility, but funding for community-based programs meant to divert youth from incarceration still fell by 25 percent due to budget cuts to the state’s judicial branch. The following year, Connecticut’s removal of minor status cases from the courts generated $4 million in annual savings, yet legislators transferred less than $650,000 to the new programs established to handle those cases.[51] And while the Connecticut Juvenile Training School is closed, there are no plans to repurpose the facility, which is critical to keeping it from reverting to a place for confinement.

In 2016, Kansas lawmakers enacted major juvenile justice reforms that marked a significant shift in state policy. The legislation, Senate Bill 367, set case- and probation-length limits for misdemeanors and certain felonies, restricting how long a youth can be under the courts’ jurisdiction. It also began phasing out facilities and out-of-home placements with more than 50 beds and limited the use of secure facilities only to the highest-risk youth or youth with high-level felonies.

Since the implementation of SB367, Kansas has cut the number of young people in confinement by over 50 percent and closed two youth prisons, saving the state millions of dollars.[52] However, racial and ethnic disparities persist, and the cost for locking up one child at the Kansas Juvenile Correctional Complex is as high as $134,000 per year.

SB367 made other changes to support reform, including by directing an estimated $72 million in savings over the first five years into the Juvenile Justice Improvement Fund (JJIF). The JJIF, which the oversight committee helps protect from being raided, is used to pay for community-based alternatives. Any money shifted into the JJIF can be used only for the purposes intended. Lawmakers can shift savings from the JJIF into the state’s general fund, but the JJIF and the protections in the legislation enable advocates and community groups to provide feedback and could encourage lawmakers to reconsider actions that could harm reinvestment.

In 2019, the state reinvested $12 million in high-quality community-based programs and other services as an alternative to incarceration. In 2020, despite the budget challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee asked the state legislature to continue to prioritize youth justice reform; the state allocated $11 million to statewide community programs, public services, and a range of other services for youth justice reform.[53] While some of the funds went back into the justice department, most were directed to community-based programs at the state or local level and services that the oversight committee prioritized, such as treatment programs.

The JJIF protections and oversight advisement only worked until the 2021 legislative session, however. Earlier deep tax cuts and the pandemic-induced recession caused significant revenue shortfalls, and pressures on the state budget were enough for lawmakers to shift $21 million of the account’s $42 million out of the JJIF.[54] This underscores the importance of protecting funds that are designated for community-based programs and other alternatives to youth incarceration.

RECLAIM Ohio gives local courts incentives to engage youth in community-based programming. Every Ohio county is eligible to receive support under RECLAIM, and funds are distributed based on a formula. How much a locality receives depends on several factors, including how much money is appropriated for the program in each year, the average number of felony adjudications over a previous number of years, and the number of days youth spend in state or community correctional facilities.[55] As a result, when counties send fewer youth in state facilities for confinement and redirect them into community-based alternatives like RECLAIM Ohio, they are saving money, reducing recidivism, and reinvesting in more efficient ways of youth rehabilitation.

A highly targeted extension effort of RECLAIM Ohio directs funding to six counties that historically committed the most youth to the state’s correctional system. The effort reduced youth prison admissions in these counties by about 80 percent over the span of a decade, from 989 youth in 2009 to just over 200 in 2019.[56] Enrolled youth are significantly less likely to reoffend upon release compared to their counterparts housed in youth prisons, according to a 2018 evaluation.[57] Estimates suggest the program costs about $9,800 per youth per year, at a total state appropriation of $6.4 million in the 2020 budget year.[58]

Another statewide intervention, the Behavioral Health/Juvenile Justice Initiative, targets assistance to youth with mental health and substance use disorders in community treatment instead of youth prisons, at an average cost of $5,170 per enrollee and average program length of six months.[59] A 2018 study of the program found that fewer than 4 percent of participants were sent to a youth prison and, over the course of enrollment, participants exhibited better educational outcomes, reduced trauma symptoms, and decreased substance use.[60]

With Ohio’s youth prison population having already fallen sharply over the last two decades, the next sensible step would be to shutter the state’s three remaining youth prisons, shift the remaining 500 detainees to other community-based housing arrangements, and redirect the savings toward proven solutions that can help affected children reenter society and thrive, while still protecting public safety. Savings from closing these facilities would include both the $96 million annual cost of running the prisons — including staff payroll, food, equipment, and supplies — as well as recouped funds from selling the buildings, equipment, and land, according to the 2021 Policy Matters report.[61]

States can reduce spending and generate revenue by closing a facility. Maintaining open facilities, even with a dwindling incarcerated population, uses funds that could be spent elsewhere, including in community-based alternatives to incarceration. Once states close facilities, they can repurpose those funds, along with the land and facilities themselves, to provide useful services to the community. States may also raise revenue by selling the buildings and land for more productive purposes.[62]

Community stakeholders, including families that have been most affected, should be included in discussions about how to repurpose youth facilities with an eye to boosting the local economy, creating high-quality, local jobs, and delivering needed services that haven’t been easily accessible. Several states and local governments have made such changes, as a recent Urban Institute report detailed:[63]

- Arizona: In 2015, the state closed the Apache County Juvenile Detention Center, which had an average of one to two youth confined per day and cost the state $1.2 million a year to operate. In 2017, the facility was converted into the LOFT Teen Community Center to offer high-school-aged youth a communal space with free internet, a music room, and other entertainment — supports that were missing from this small rural community. The costs were minimal and the effort involved help from in-house probationary staff and renovation ideas from several high school students.

- California: The Fred C. Nelles School, the longest-running youth correctional facility in California and an historic landmark, closed in 2004, making 74 acres of land available to be repurposed. In 2009, Brookfield Residential won the bid for the property to transform it into commercial space and hundreds of homes to address a local housing shortage. This development was anticipated to produce $1 million in net city revenue and boost the city economy.

- Michigan: THRIVE Collaborative won the 2017 land bid for Washtenaw County Juvenile Detention Center, closed in 2003, with plans to repurpose the area into a sustainable mixed-income housing community with zero net carbon emissions. The plan sets aside 40 percent of the homes for affordable housing, and the developers are using an environmental and equity framework by adding solar energy and community gardens.

- Texas: In 2014, the Texas legislature mandated the repurposing of the land housing the Al Price Juvenile Correctional Facility, closed in 2011, for public use. The Beaumont Dream Center in Jefferson County was created to provide social services, housing, and recovery support after the state paid millions of dollars on maintenance in the years after the youth prison was closed. In partnership with the Harbor House Foundation, the Dream Center bought the property and will absorb all maintenance and renovation costs after an initial grace period, saving the state money to reinvest into youth services.

State and local policies often result in young people, especially young people of color, being incarcerated and harmed. That harm extends to their families and communities and adds to the many barriers young people of color face due to bias and discrimination. States and localities should reevaluate their policies of incarcerating youth and of maintaining youth detention facilities, and chart new paths that can save public dollars, allow for new investments in youth and their communities, and repurpose vacant facilities to boost communities’ long-term economic and social health and well-being.

Enacting these smart reforms is just a start. While states can reform their juvenile justice systems and use the savings productively, they can also increase broader public investments in schools, transit, parks and recreation, libraries, and other services targeted particularly to youth of color, their families, and their communities. These broader investments, often neglected in low-income communities of color, are needed to produce the sort of environment that will allow all children to thrive. Additionally, states can create oversight committees or advisory boards dedicated to creating new laws, policies, and practices that ensure young people are not involved in the criminal justice system and have the opportunity to reach their full potential in a community that is well-resourced and able to meet their needs.

This report, the first product published by CBPP solely focused on youth justice reform and reinvestment, was made possible by the generous contributions of individuals and coalitions across the country who support justice reform. The author would like to thank her State Fiscal Policy team colleagues for their feedback and assistance in the drafting of this report, as well as reviewers from the Youth First Initiative, The Sentencing Project, Urban Institute Justice Policy Center, and Prison Policy Initiative. Also, thank you to the staff of Connecticut Voices for Children, Kansas Action for Children and their partner Kansas Appleseed, and Policy Matters Ohio, and their partners working on youth justice reforms in those states. Finally, thank you to the CBPP communications team for their thoughtful edits, graphics, and getting this published.