As is increasingly well known, a growing number of taxpayers will become subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax over the next ten years if relief from the tax (which has been provided by Congress on a year-to-year basis) is not extended. A growing fraction of those affected by the AMT will be middle- or upper-middle class families.

The Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, Citizens for Tax Justice, and others have outlined options for revenue-neutral AMT reform. These proposals would restructure the AMT to bring it closer to its original purpose of targeting high-income taxpayers paying little in income taxes, while exempting most or all middle- and upper-middle income taxpayers.[1]

In contrast, some in Congress have called for outright repeal of the AMT. On January 4, Finance Committee Chair Max Baucus and Ranking Member Charles Grassley introduced a bill that would repeal the tax beginning in 2007. The legislation does not include any offsets to the cost of repeal but, in introducing the bill, Senator Baucus indicated support for the new Congress’s intention to provide tax relief “in a fiscally responsible way." Senator Grassley however stated, “It’s unfair to raise taxes to repeal something with serious unintended consequences like the AMT.”[2]

Repealing the AMT without making up the revenue from other sources would carry a staggering cost.

- According to estimates by the Tax Policy Center, AMT repeal would cost more than $800 billion in lost revenues over the next decade (2008-2017), if the income-tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 are allowed to expireas scheduled at the end of 2010.

- Moreover, if these tax cuts are extended, the cost of AMT repeal would equal more than $1.5 trillion over the next ten years.[3]

Extending the 2001 and 2003 income-tax cuts nearly doubles the cost of AMT repeal because the tax cuts push millions of additional taxpayers onto the AMT, increasing the amount of revenue that the tax collects and raising the cost of eliminating it. (Another way of looking at this is that the AMT masks the true dimensions of the costs of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts because it effectively recaptures a portion of those tax cuts.)[4]

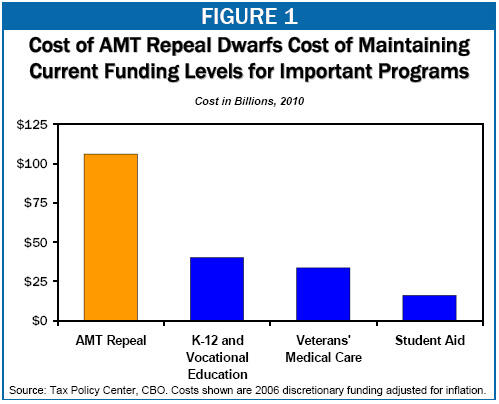

To grasp the magnitude of these revenue losses, it is helpful to compare them to spending on various national priorities. In 2010 alone, AMT repeal is projected to cost $106 billion. These revenue losses dwarf the cost of continuing to fund K-12 and vocational education, hospital and medical care for veterans, or student aid at current levels, adjusted for inflation (see Figure 1).[5]

It may also help to compare the cost of AMT repeal with the cost of other large tax cuts. Repeal of the estate tax, for example, is widely recognized as very expensive and is increasingly regarded as unaffordable. It was rejected by the Senate last year, with many Senators citing cost considerations as the reason for their votes. Yet the cost of estate-tax repeal is less than the cost of AMT repeal over the long run.

- Estate-tax repeal would lose $91 billion in revenues in 2017, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (2017 is the last year for which the Joint Tax estimates are available). If the 2001 and 2003 income-tax cuts expire, the cost of AMT repeal in 2017 would be $106 billion, according to the Tax Policy Center, somewhat more than the cost of estate-tax repeal. In addition, the cost of AMT repeal would grow much more rapidly from year to year than the cost of estate-tax repeal.

- Furthermore, if the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are extended, the cost of AMT repeal in 2017 would be $249 billion, or more than two and a half times the cost of estate-tax repeal in the same year.

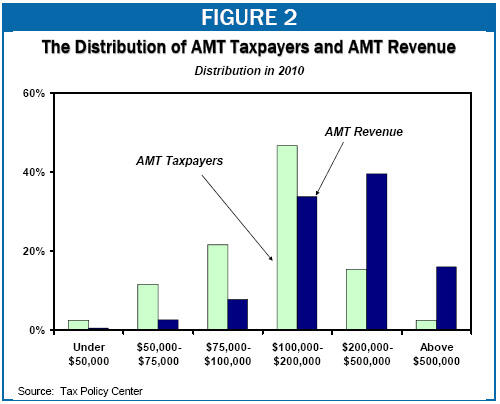

Much of the concern surrounding the AMT has to do with the fact that, over time, an increasing number of middle- and upper-middle income households will be affected by the tax, and these households will make up an increasing fraction of AMT taxpayers. By 2010, if no relief from the AMT were provided — that is, if the AMT relief that expired at the end of 2006 were not extended, a very unlikely scenario — some 80 percent of AMT taxpayers would have incomes under $200,000, about a third would have incomes under $100,000, and 14 percent would have incomes under $75,000. Some supporters of AMT repeal have portrayed it as an urgently needed solution to this “middle-class problem.”

But while most AMT taxpayers have incomes under $200,000, most AMT revenue comes from the 4 percent of households with incomes over $200,000, according to Tax Policy Center estimates (see Figure 2).[6] For this reason, more than half of the benefits of AMT repeal through 2010 would go to the 4 percent of households with incomes over $200,000.[7]

-

In 2010, some 55 percent of the tax-cut benefits from repealing the AMT would go to households with incomes exceeding $200,000.

-

Some 90 percent of the tax-cut benefits would go to the one-sixth of households with incomes over $100,000.

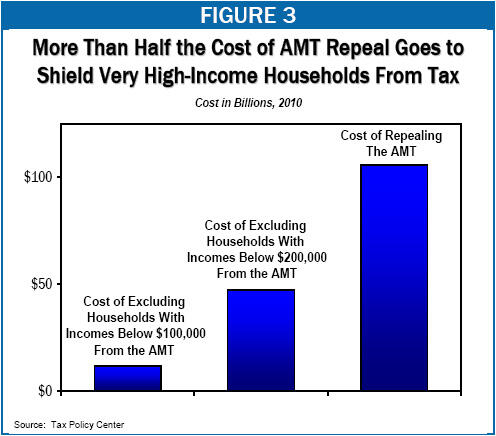

If Congress’s objective is to remove middle- and upper-middle income taxpayers from the AMT, repealing the tax goes far beyond what is needed to achieve that goal. In 2010, for example, it would cost about $11 billion to remove all households with incomes below $100,000 from the AMT and about $47 billion to remove all households with incomes below $200,000. Repeal would cost over $100 billion (see Figure 3).

While removing only middle- and upper-middle income taxpayers from the AMT would be considerably cheaper than repeal, it nevertheless would carry a very high price tag. The solution Congress has adopted so far has been to increase the AMT exemption each year by enough to keep the number of AMT taxpayers from increasing dramatically and to prevent large numbers of additional middle- and upper-middle income households from becoming subject to the tax. Continuing these AMT “patches” for another ten years (2008-2017) would cost more than $500 billion if the 2001 and 2003 income-tax cuts expire, according to the Congressional Budget Office. If these tax cuts are extended, the cost of continuing the annual AMT patches would be more than $1 trillion.

Revenue losses of this magnitude are dangerously large given the nation’s grim long-term fiscal outlook. With the federal government facing escalating budget deficits in future decades, it would be irresponsible to add to these deficits the costs of a massive, unpaid-for AMT fix.

As noted above, the Urban Institute-Brookings Tax Policy Center, Citizens for Tax Justice, and others have outlined various options for revenue-neutral AMT reform. Incoming Ways and Means Committee Chair Charles Rangel has embraced the principle of offsetting the cost of AMT changes. The Bush Administration, as well, has called for dealing with the AMT in a deficit-neutral manner, in the context of fundamental tax reform. These calls should be heeded. If policymakers decide to tackle the task of permanent AMT reform, they should step up to the plate and offset the costs of resolving this matter.