Protecting Students and Taxpayers

Why the Trump Administration Should Heed History of Bipartisan Efforts

End Notes

[1] Spiros Protopsaltis is a Visiting Associate Professor of Education Policy in the College of Education and Human Development at George Mason University and served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Higher Education and Student Financial Aid at the U.S. Department of Education from March 2015 to January 2017. Libby Masiuk served as a Senior Policy Advisor at the U.S. Department of Education from May 2015 to January 2017.

[2] “Total Student Aid and Nonfederal Loans in 2016 Dollars over Time,” The College Board, 2017. https://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid/figures-tables/total-student-aid-and-nonfederal-loans-2016-dollars-over-time.

[3] Abuses in Federal Student Aid Programs: Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Affairs, United States Senate, 101st Cong., Second Session, February 20, 1990. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED334955.pdf.

David Halperin, “Law Enforcement Investigations and Actions Regarding For-Profit Colleges,” Republic Report, November 6, 2017, https://www.republicreport.org/2014/law-enforcement-for-profit-colleges/;

[4] David Whitman, “Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal,” The Century Foundation, January 24, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/truman-eisenhower-first-gi-bill-scandal/.

[5] Veterans Readjustment Assistance Act of 1952, P.L. 550, H.R. 7656, July 16, 1952, p. 667, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-66/pdf/STATUTE-66-Pg663.pdf.

[6] Letter from Donald Johnson, Administrator at the Veterans Administration to Senator Vance Hartke, Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, September 22, 1971. “The findings and experience of the select committee were utilized in drafting the Korean conflict GI bill (Public Law 550, 82d Congress). History has shown that the Korean program met with marked success and most of the areas of abuse detected in the earlier World War II program were eliminated.” Educational Benefits Available for Returning Vietnam Era Veterans: Hearing before the Committee On Veteran’s Affairs, United States Senate, Ninety-Second Congress, March 23, 1972, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbHo3N0tya29uRjA/view.

[7] Daniel J. Riegel, “Closing the 90/10 Loophole in the Higher Education Act: How to Stop Exploitation of Veterans, Protect American Taxpayers, and Restore Market Incentives to the For-Profit College Industry,” The George Washington Law Review (January 2013), http://www.gwlr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Riegel_81_1.pdf.

[8] Whitman, “Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal.”

[9] Margaret Mattes, “The GOP Has a Long History of Cracking Down on ‘Sham Schools,’” The Century Foundation, January 12, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/gop-long-history-cracking-sham-schools/.

[10] David Whitman, “Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams,” The Century Foundation, February 13, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/vietnam-vets-new-student-loan-program-bring-new-college-scams/.

[12] Robert Shireman, “Colleges Highly Dependent on Federal Aid Should Prove Their Worth,” The Century Foundation, February 27, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/colleges-highly-dependent-federal-aid-prove-worth/.

Meagan Day, “For-profit colleges have been taking advantage of veterans since WWII.” Timeline, May 24, 2016, https://timeline.com/for-profit-colleges-have-been-taking-advantage-of-veterans-since-wwii-344ab3015543.

[13] Shireman, “Colleges Highly Dependent on Federal Aid Should Prove Their Worth.”

[14] “Many Proprietary Schools Do Not Comply with Department of Education’s Pell Grant Program Requirements,” U.S. General Accounting Office, August 20, 1984, http://www.gao.gov/assets/150/142095.pdf.

[15] Robert Shireman, “The Covert For-Profit,” The Century Foundation, September 22, 2015, https://tcf.org/content/report/covert-for-profit/.

[16] David Whitman, “When President George H. W. Bush ‘Cracked Down’ on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, March 9, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/president-george-h-w-bush-cracked-abuses-profit-colleges/.

[17] Abuses in Federal Student Aid Programs: Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Affairs, p. 5. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED334955.pdf .

[18] Other concerns included: a) Schools receiving full disbursements of student loans even if students dropped out within the first few weeks of school; b) falsification of student answers to tests that could be taken in lieu of having received a high school diploma in order to receive federal student aid, also known as “ability to benefit” tests; c) aggressive recruitment of students in exchange for gifts, money, and other incentives for recruiters; d) the Education Department’s inadequate assessment of schools’ financial soundness; and e) the Department’s inadequate program review process and its inability to prohibit poor performing institutions from continuing to receive Title IV aid due to the lack of a recertification process.

[19] “Abuses In Federal Student Aid Programs,” Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, May 17, 1991, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED332631.pdf.

[20] Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, H.R.5835, 101st Cong., (1990), H.Rpt. 101-881, https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/5835.

[21] “National Student Loan Two-year Default Rates,” U.S. Department of Education, 2011, https://www2.ed.gov/offices/OSFAP/defaultmanagement/defaultrates.html.

[22] Whitman, “When President George H. W. Bush ‘Cracked Down’ on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges.”

[23] Whitman, “Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal.”

[24] James Coleman and Richard Vedder, “For-Profit Education in the United States: A Primer,” Center for College Affordability and Productivity, May 2008, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED536281.pdf.

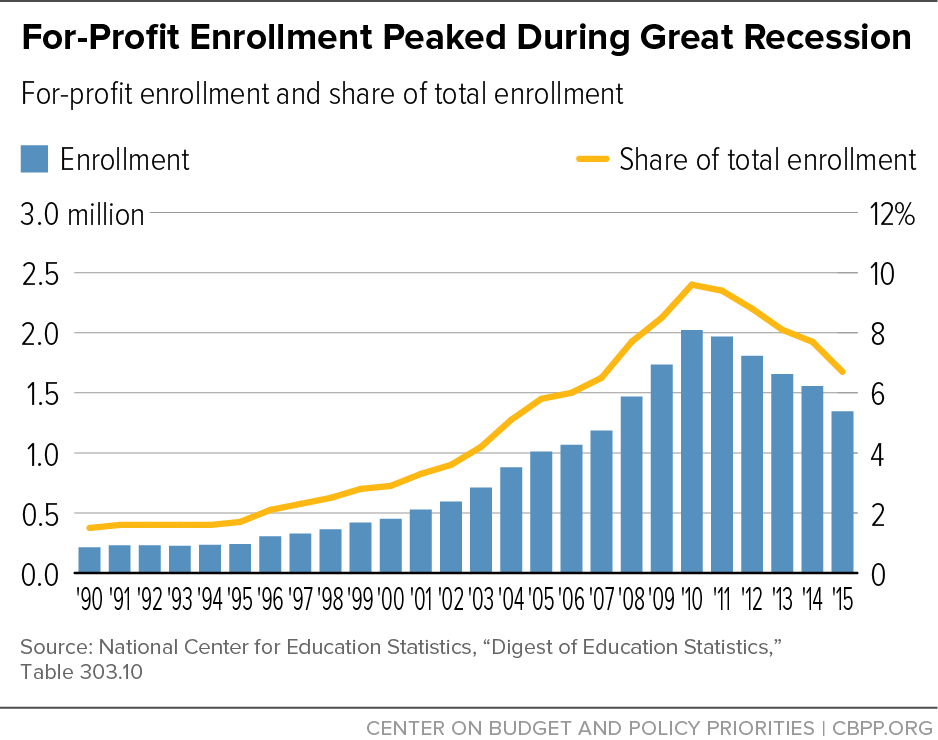

[25] Table 303.10: “Total fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by attendance status, sex of student, and control of institution: Selected years, 1947 through 2026,” National Center for Education Statistics, February 2017. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_303.10.asp.

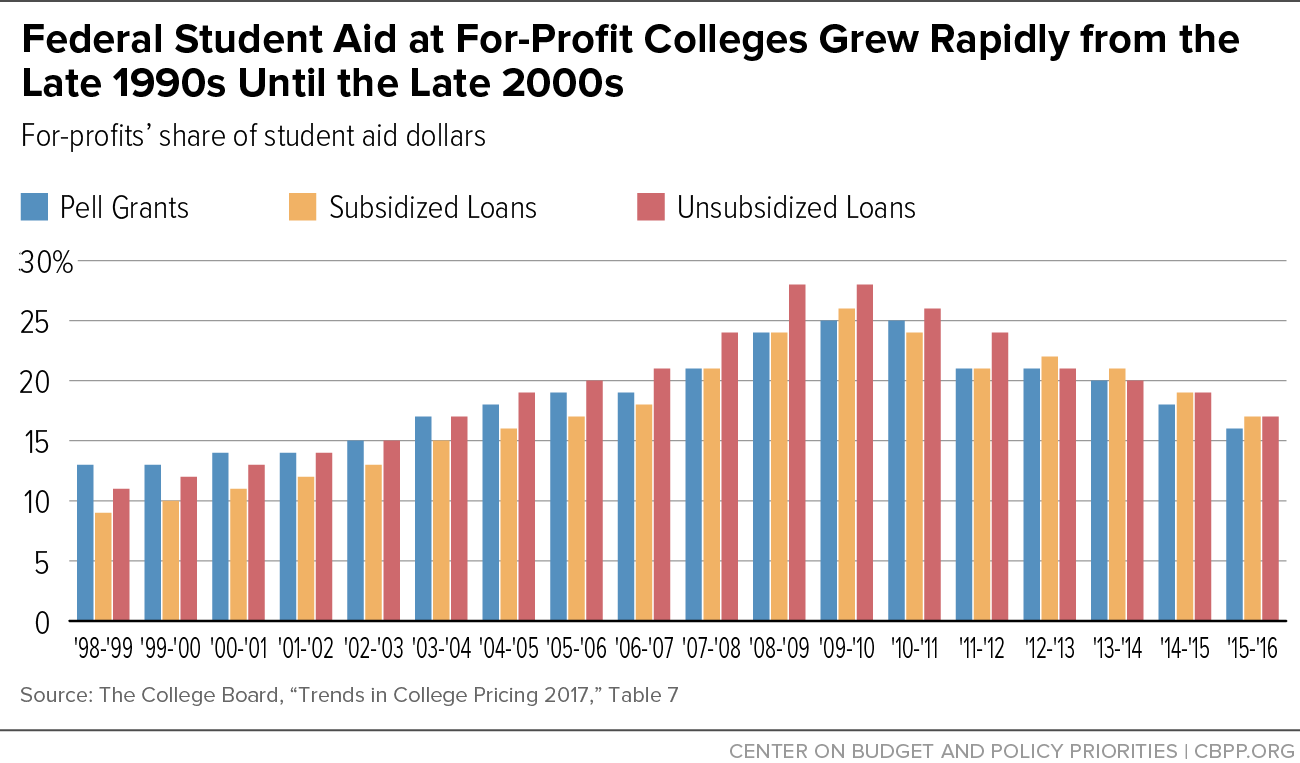

[26] “Percentage Distribution of Federal Aid Funds by Sector over Time,” College Board, https://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid/figures-tables/percentage-distribution-federal-funds-sector-over-time.

[27] “2016-2017 Grant and Loan Volume by School Type,” U.S. Department of Education, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/sites/default/files/fsawg/datacenter/library/SummarybySchoolType.xls.

[28] A. J. Angulo, Diploma Mills: How For-Profit Colleges Stiffed Students, Taxpayers, and the American Dream, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), p. 113.

[29] David Halperin, “Who Owns The Awful Corinthian Colleges? Wells Fargo, Marc Morial, Pension Funds,” Huffington Post, updated February 22, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/davidhalperin/who-owns-the-awful-corint_b_4101323.html.

[30] Executive Summary of “For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success,” Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, United States Senate, July 30, 2012, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/ExecutiveSummary.pdf.

[31] Jorge Klor de Alva and Andrew Rosen, “Inside the For-Profit Sector in Higher Education,” Forum Futures 2012, https://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ff1204s.pdf.

[32] Table 303.20: “Total fall enrollment in all postsecondary institutions participating in Title IV programs and annual percentage change in enrollment, by degree-granting status and control of institutions: 1995 through 2015.” National Center for Education Statistics, February 2017, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_303.20.asp.

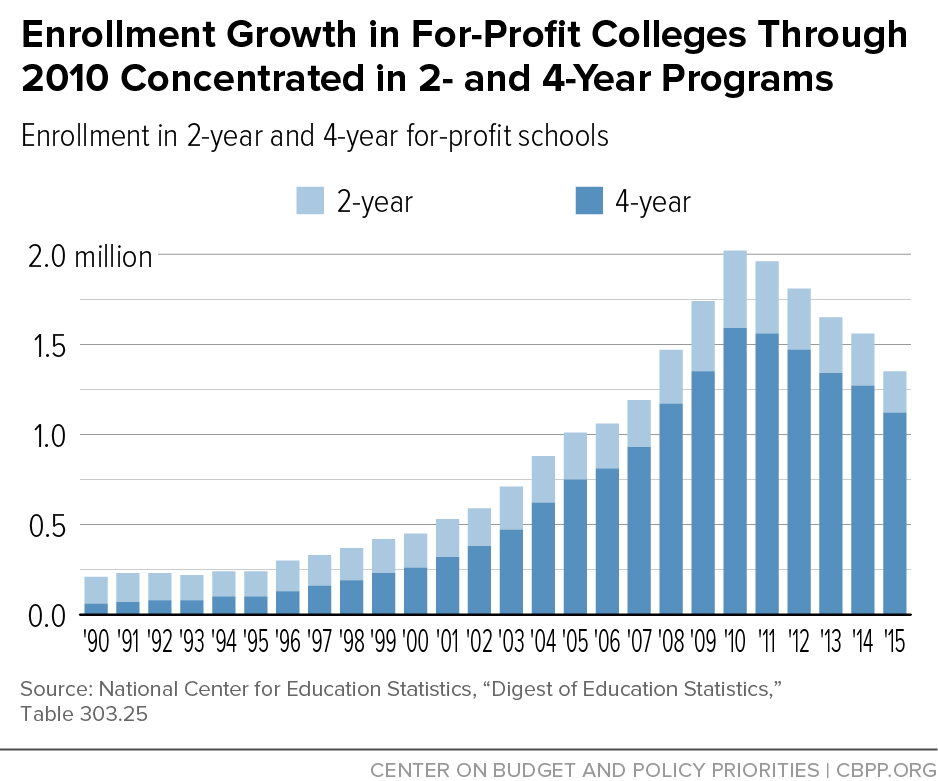

[33] “Table 302.25: “Total fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of institution: 1970 through 2015,” National Center for Education Statistics, February 2017, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_303.25.asp.

[34] Terese Rainwater, “The Rise and Fall of SPRE: A Look at Failed Efforts to Regulate Postsecondary Education in the 1990s,” American Academic, (March 2006), http://co.aft.org/files/article_assets/462D6042-CAA9-E7BB-509EA8C793E87C8D.pdf.

[35] “High-Risk Series: Student Financial Aid,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, February 1, 1997, http://www.gao.gov/products/HR-97-11.

[36] “Number and percentage of students enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by distance education participation, and level of enrollment and control of institution: Fall 2014,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=80; CBO identified “distance education, particularly at for-profit institutions” as one of three factors that accounted for most of the increase in Pell expenditures during the Great Recession. “The Pell Grant Program: Recent Growth and Policy Options,” Congressional Budget Office, September 5, 2013, p. 10, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44448.

[37] “VA Education Benefits: Student Characteristics and Outcomes Vary across Schools,” Government Accountability Office, July 2013, http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/656204.pdf.

[38] “Is the New G.I. Bill Working?: For-Profit Colleges Increasing Veteran Enrollment and Federal Funds,” Health, Education, Labor, and Pension Committee, United States Senate, July 30, 2014, http://static.politico.com/72/22/6167b3b94a2a83bbc73f780180bc/senate-help-gi-bill-report-2014.pdf.

[39] Clifton B. Parker, “The Great Recession spurred student interest in higher education, Stanford expert says,” Stanford News, March 6, 2015, https://news.stanford.edu/2015/03/06/higher-ed-hoxby-030615/.

[40] Bridget Terry Long, “The Financial Crisis and College Enrollment: How Have Students and Their Families Responded?” in How the Financial Crisis and Great Recession Affected Higher Education, eds. Jeffrey R. Brown and Caroline M. Hoxby (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), pp. 209-233, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12862.

[41] Paul Fain, “Recession and Completion,” Inside Higher Ed, November 18, 2014, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/11/18/enrollment-numbers-grew-during-recession-graduation-rates-slipped.

[42] Peter S. Goodman, “In Hard Times, Lured into Trade School and Debt,” New York Times, March 13, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/14/business/14schools.html?pagewanted=all.

[43] Pauline Abernathy, “Drowning in Debt: Financial Outcomes of Students at For-Profit Colleges,” testimony before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, June 7, 2011, https://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pub_files/Abernathy_testimony_June_7_2011.pdf; Robert Shireman, “The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat,” The Century Foundation, January 24, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/profit-college-story-scandal-regulate-forget-repeat/; Lucinda Shen, “For-Profit Colleges Account for a Third of All Federal Student Loan Defaults,” Fortune, September 29, 2016, http://fortune.com/2016/09/29/student-loan-defaults-2/.

[44] David Halperin, “Law Enforcement Investigations and Actions Regarding For-Profit Colleges.” Republic Report. November 6, 2017, https://www.republicreport.org/2014/law-enforcement-for-profit-colleges/.

[45] Goldie Blumenstyk, “Government Investigations and Suits Against For-Profit Colleges: the Grid,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 28, 2014, http://www.chronicle.com/blogs/bottomline/government-investigations-and-suits-against-for-profit-colleges-the-grid/; “Government Investigations and Lawsuits Involving For-profit Schools,” National Consumer Law Center, May 2014, https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/for-profit-gov-investigations.pdf; Halperin, "Law Enforcement Investigations”; James R. Hood, “Attorneys General warn of ‘open season’ on students attending for-profit colleges,” Consumer Affairs, February 23, 2017, https://www.consumeraffairs.com/news/attorneys-general-warn-of-open-season-on-students-attending-for-profit-colleges-022317.html.

[46] Michael Stratford, “Corinthian Closes for Good,” Inside Higher Ed, April 27, 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/04/27/corinthian-ends-operations-remaining-campuses-affecting-16000-students.

[47] “For-Profit College Company to Pay $95.5 Million to Settle Claims of Illegal Recruiting, Consumer Fraud and Other Violations,” The United States Department of Justice, November 16, 2015, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/profit-college-company-pay-955-million-settle-claims-illegal-recruiting-consumer-fraud-and.

[48] Patricia Cohen, “ITT Educational Services Closes Campuses,” New York Times, September 6, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/07/business/itt-educational-services-closes-its-campuses.html.

[49] Paul Fain, “CFPB Penalizes Bridgepoint Over Private Loans,” Inside Higher Ed, September 13, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2016/09/13/cfpb-penalizes-bridgepoint-over-private-loans.

[50] Jim Puzzanghera and Ronald D. White, “Closing of ITT Tech and other for-profit schools leaves thousands of students in limbo,” Los Angeles Times, September 12, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-for-profit-schools-20160912-snap-story.html.

[51] “Department of Education Establishes New Student Aid Rules to Protect Borrowers and Taxpayers,” The U.S. Department of Education, October 28, 2010, https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/department-education-establishes-new-student-aid-rules-protect-borrowers-and-taxpayers.

[52] “[T]he Department believes that the language in section 487(a)(20) of the HEA is clear, and that the elimination of all of the regulatory safe harbors reflected in current Sec. 668.14(b)(22)(ii) would best serve to effectuate congressional intent. The Department previously explained that it was adopting the safe harbors based on a ‘purposive reading of section 487(a)(20) of the HEA.'' 67 FR 51723 (August 8, 2002). Since that time, however, the Department's experience demonstrates that unscrupulous actors routinely rely upon these safe harbors to circumvent the intent of section 487(a)(20) of the HEA. As such, rather than serving to effectuate the goals intended by Congress through its adoption of section 487(a)(20) of the HEA, the safe harbors have served to obstruct those objectives.” “Program Integrity Issues; Proposed Rule,” U.S. Department of Education, June 18, 2010, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-06-18/html/2010-14107.htm.

[53] Title 34: Education, Part 668—Student Assistance General Provisions, Sec. 668.71, Scope and special definitions, November 1, 2016, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/34/668.71.

[54] “The Department believes that in its stewardship of the title IV, HEA programs, it is essential to monitor the claims made by institutions not only to students and prospective students, but also those made to the Department's partners who help maintain the integrity of these programs. While it is likely that other oversight agencies will respond appropriately to any substantial misrepresentations that are made to them, only the Department has the overall responsibility for preserving the propriety of the administration of the title IV, HEA programs.” “Program Integrity Issues; Final Rule,” U.S. Department of Education, October 29, 2010, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-10-29/pdf/2010-26531.pdf.

[55] “Program Integrity Issues; Final Rule.”

[56] “Since accrediting agencies generally require that an institution be legally operating in the State, we are concerned that the checks and balances provided by the separate processes of accreditation and State legal authorization are being compromised.” “Program Integrity Issues; Proposed Rule.”

[57] Doug Lederman, “For-Profit Colleges Open Another Front,” Inside Higher Ed, January 24, 2011, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2011/01/24/for_profit_college_group_sues_education_department_over_new_rules.

[58] Career College Association D/B/A Association Of Private Sector Colleges And Universities v. Secretary Of The Department Of Education Arne Duncan and The Department Of Education, Case: 1:11-cv-00138-RMC, January 21, 2011, http://legaltimes.typepad.com/files/complaint-8.pdf.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Stephen Burd, “For Third Time, APSCU Fails to Get Courts to Strike Down Incentive Compensation Rule,” New America, October 6, 2014, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/third-time-apscu-fails-get-courts-strike-incentive-compensation-rule/.

[61] Paul Fain, “Mixed Decision on Integrity Rules,” Inside Higher Ed, June 6, 2012, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/06/06/us-appeals-court-issues-mixed-decision-profit-challenge-rules.

[62] “U.S. Department of Education Fines Corinthian Colleges $30 million for Misrepresentation,” U.S. Department of Education, April 14, 2015, https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-fines-corinthian-colleges-30-million-misrepresentation.

[63] Gretchen Morgenson, “Corinthian Colleges Used Recruiting Incentives, Documents Show,” New York Times, June 22, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/23/business/corinthian-colleges-used-recruiting-incentives-documents-show.html.

[64] Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis, “A crisis in student loans? How changes in the characteristics of borrowers and in the institutions they attended contributed to rising loan defaults,” Brookings Institute, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/a-crisis-in-student-loans-how-changes-in-the-characteristics-of-borrowers-and-in-the-institutions-they-attended-contributed-to-rising-loan-defaults/.

[65] “The Negotiated Rulemaking Process for Title IV Regulations - Frequently Asked Questions,” U.S. Department of Education, last updated August 25, 2008, https://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/reg/hearulemaking/hea08/neg-reg-faq.html.

[66] “Fact Sheet On Final Gainful Employment Regulations,” U.S. Department of Education, October 30, 2014, https://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/reg/hearulemaking/2012/gainful-employment-fact-sheet-10302014.pdf.

[67] Paul Fain, “Nowhere to Go,” Inside Higher Ed, May 27, 2014, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/05/27/gainful-employment-will-hit-profits-and-their-students-hard-industry-study-finds.

[68] Shaun McAlmont, “Q3 2014 Earnings Call,” presentation at Career Education Corporation Third Quarter 2014 Earnings Conference Call, November 4, 2014, https://seekingalpha.com/article/2639475-lincoln-educational-services-linc-ceo-shaun-mcalmont-on-q3-2014-results-earnings-call-transcript; Scott Steffey, “Q3 2014 Earnings Call,” presentation at Career Education Corporation Third Quarter 2014 Earnings Conference Call, November 6, 2014, https://seekingalpha.com/article/2653235-career-educations-ceco-ceo-scott-steffey-on-q3-2014-results-earnings-call-transcript.

[69] Kelly Field, “For-Profit Colleges Win Major Concessions in Final ‘Gainful Employment’ Rule,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, June 2, 2011, http://www.chronicle.com/article/for-profit-colleges-win-major/127744.

[70] Kaplan University, “Promising and Practical Strategies to Increase Postsecondary Success: the Kaplan Commitment,” U.S. Department of Education, April 30, 2012, http://www2.ed.gov/documents/college-completion/the-kaplan-commitment.pdf; Chadwick Matlin, “The Reform of For-Profit Colleges: Can They Give Up Their Predatory Ways?” The Atlantic, September 20, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/09/the-reform-of-for-profit-colleges-can-they-give-up-their-predatory-ways/279850/.

[71] David Halperin, “Gainful Employment Rule for For-Profit Colleges: Eminently Fixable, Eminently Necessary,” Huffington Post, April 15, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/davidhalperin/gainful-employment-rule-f_b_3084580.html.

[72] Andy Thomason, “Gainful-Employment Rule Survives For-Profit Group’s Court Challenge,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, June 23, 2015, http://www.chronicle.com/blogs/ticker/gainful-employment-rule-survives-for-profit-groups-court-challenge/101079.

[73] Ashley A. Smith, “Reshaping the For-Profit,” Insider Higher Ed, July 15, 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/07/15/profit-industry-struggling-has-not-reached-end-road.

[74] Press Release, “Education Department Releases Final Debt-to-Earnings Rates for Gainful Employment Programs,” U.S. Department of Education, January 9, 2017, https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/education-department-releases-final-debt-earnings-rates-gainful-employment-programs; Erica Perez, “For-profit Career Education Corp. to close 23 campuses after enrollment plummets,” The Hechinger Report, November 14, 2013, http://hechingerreport.org/for-profit-career-education-corp-to-close-23-campuses-after-enrollment-plummets/.

[75] David Halperin, “What For-Profit Colleges Really Think About the Gainful Employment Rule,” Republic Report, January 6, 2017, https://www.republicreport.org/2017/what-for-profit-colleges-really-think-about-the-gainful-employment-rule/.

[76] Pauline Abernathy, “What Does a Failing Program Look Like?” The Institute for College Access & Success, March 7, 2017, http://ticas.org/blog/what-does-failing-program-look.

[77] Andrew Kreighbaum, “Overburdened with Debt,” Inside Higher Ed, January 10, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/10/federal-data-show-hundreds-vocational-programs-fail-meet-new-gainful-employment.

[78] Press Release, “Education Department Releases Final Debt-to-Earnings Rates for Gainful Employment Programs,” U.S. Department of Education, January 9, 2017, https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/education-department-releases-final-debt-earnings-rates-gainful-employment-programs.

[79] Paul Fain, “Nowhere to Go,” Insider Higher Ed, May 27, 2014, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/05/27/gainful-employment-will-hit-profits-and-their-students-hard-industry-study-finds.

[80] Kevin Carey, “DeVos Is Discarding College Policies That New Evidence Shows Are Effective,” New York Times, June 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/30/upshot/new-evidence-shows-devos-is-discarding-college-policies-that-are-effective.html?_r=0.

[81] David J. Deming, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Labor Market Returns to a For-Profit College Education,” NBER Working Paper No. 17710, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17710.pdf.

[82] Stephanie Riegg Cellini and Latika Chaudhary, “The Labor Market Returns to a For-profit College Education,” NBER Working Paper No. 18343, August 2012, http://www.nber.org/papers/w18343.pdf.

[83] Kevin Lang and Russell Weinstein, “Evaluating Student Outcomes at For-profit Colleges,” NBER Working Paper No. 18201, June 2012, http://www.nber.org/papers/w18201.pdf.

[84] David Deming, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence Katz, “For-Profit Colleges,” Future of Children 23, no. 1 (2013), 137-63, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/12553738/11434354.pdf?sequence=1.

[85] Yuen Ting Liu and Clive Belfield, “Evaluating For-Profit Higher Education: Evidence from the Education Longitudinal Study,” Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment, September 2014, http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/capsee-evaluating-for-profit-els.pdf.

[86] Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis, “A crisis in student loans? How changes in the characteristics of borrowers and in the institutions they attended contributed to rising loan defaults,” Brookings Institution, Fall 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/a-crisis-in-student-loans-how-changes-in-the-characteristics-of-borrowers-and-in-the-institutions-they-attended-contributed-to-rising-loan-defaults/.

[87] David J. Deming et al., “The Value of Postsecondary Credentials in the Labor Market: An Experimental Study,” Harvard University, September 2015, http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/lkatz/files/resumeauditstudy_final_092114_dd.pdf.

[88] Rajashri Chakrabarti, Michael Lovenheim, and Kevin Morris, “Who Falters at Student Loan Payback Time?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, September 9, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/09/who-falters-at-student-loan-payback-time.html.

[89] Stephanie Riegg Cellini and Nicholas Turner, “Gainfully Employed? Assessing the Employment and Earnings of For-Profit College Students Using Administrative Data,” National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22287.

[90] Program Review Report of the Title IV Federal Student Financial Assistance at University of Phoenix, U.S. Department of Education, February 5, 2004, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7adHdBE6w3mZWw1U1Z5TEdJNnc/view.

[91] John P. Higgins, Jr., statement before the House Committee on Government Reform, May 26, 2005, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oig/auditrpts/stmt052005.doc.

[92] “Proprietary Schools: Improved Department of Education Oversight Needed to Help Ensure Only Eligible Students Receive Federal Student Aid,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, October 14, 2009, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-127T.

[93] “For-Profit Colleges: Undercover Testing Finds Colleges Encouraged Fraud and Engaged in Deceptive and Questionable Marketing Practices,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, August 4, 2010, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-948T.

[94] “For-Profit Schools: Experiences of Undercover Students Enrolled in Online Classes at Selected Colleges,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, October 2011, http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d12150.pdf.

[95] “Higher Education: Information on Incentive Compensation Violations Substantiated by the U.S. Department of Education,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, February 23, 2010, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-370R.

[96] “Postsecondary Education: Student Outcomes Vary at For-Profit, Nonprofit, and Public Schools,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, December 2011, http://www.gao.gov/assets/590/586738.pdf.

[97] “For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success,” Committee On Health, Education, Labor, And Pensions, United States Senate, July 30, 2012, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CPRT-112SPRT74931/pdf/CPRT-112SPRT74931.pdf.