- Home

- Poverty And Inequality

- Bolstering Family Income Essential To He...

Policy Brief: Bolstering Family Income Essential to Help Children Emerge From Current Crisis

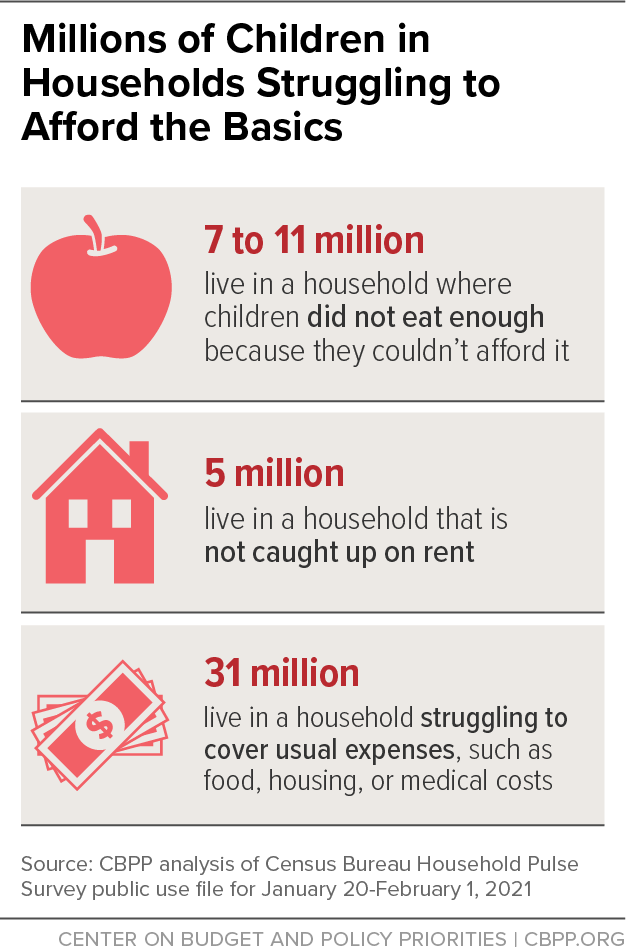

Tens of millions of people, especially in households with children, are struggling to put food on the table, make rent, or cover basic expenses. At least 10 million children have a family member who is unemployed or who lacks paid work because of the pandemic. Children’s alarming rates of food and housing hardship risk inflicting sustained harm to the well-being and potential of a generation, but a strong package of income support policies can lower this risk and help more children realize their potential. While relief measures enacted last year have helped, it is clear that throughout the crisis millions of families with children have struggled and that without more help, hardship will remain high for months to come.[1]

Rates of household hardship are high for children in all racial and ethnic groups: nearly 31 million children (43 percent of them) live in a household that reported difficulty covering usual expenses such as food, housing, and medical expenses. (See Figure 1.) But due largely to structural racism and discrimination in education, housing, employment, and health care, among other factors, hardship rates are far higher for some households than others. Some 6 out of 10 children in Black households and in Latino households live in ones having difficulty covering these expenses, compared to 3 in 10 children in Asian and in white households (based on the race or ethnicity of the adult respondent in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, the source of the data).

Hardship and Financial Strain Can Take a Lasting Toll on Children

A large body of research links hardships such as inability to afford adequate food or housing to worse child outcomes. The effects of such hardships, which range from nutrient deficiency to disrupted schooling when families move frequently from home to home, can have lifelong consequences.

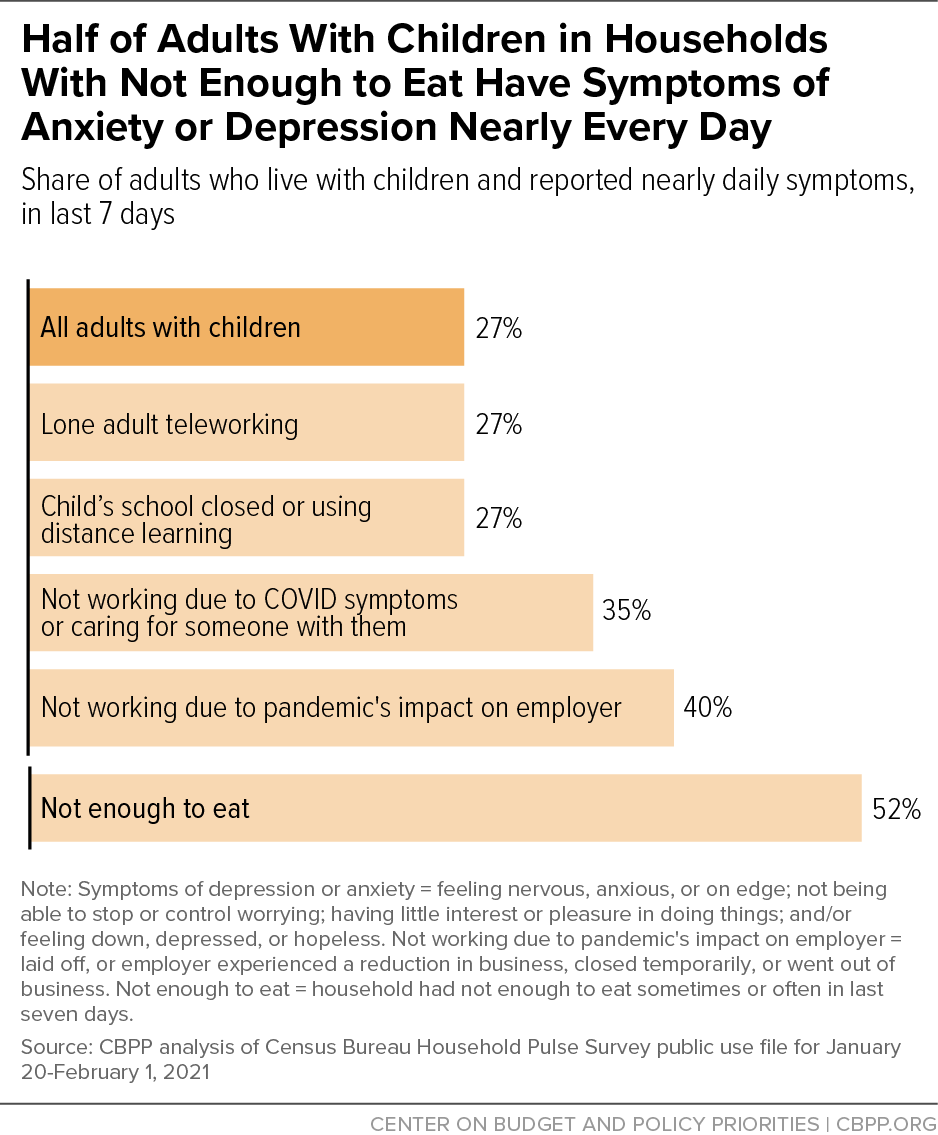

Part of what makes these and similar hardships dangerous for children, experts say, is stress. Intense worry about meeting a family’s urgent needs can preoccupy parents or other caregivers, hindering them from giving the kind of steady and reassuring parenting that helps children thrive.

When a parent’s stress is strong and sustained early in their child’s life or even during pregnancy, it may result in what is known as “toxic stress” for the child, which is associated with measurable changes in brain structure and later cognitive damage and reduced health. “[The] results show that when caregivers feel stress and uncertainty about paying their bills and providing the basics for their families, negative emotional effects cascade downstream to their children,” say researchers who have been tracking stress among adult caregivers throughout the pandemic.

The connection between economic hardship and worse mental health stands out even at a time when families are experiencing many strains (and the pandemic has often made it more difficult to access or afford mental health care). In households that include children and that did not have enough to eat sometimes or often in the last seven days, fully half (52 percent) of Pulse adults said they felt symptoms of anxiety and depression “nearly every day.” While many factors are at play, this rate was high even compared with other potential challenges of the pandemic. (See Figure 2.)

Poverty-Reducing Interventions Can Help Children’s Future Opportunities

Providing more food, housing, income, and other relief is linked with a range of long-term positive outcomes for children.

More Food Assistance: A Promising Strategy to Boost Children’s Lifetime Health, Earnings

Studies link food insecurity among children with reduced intake of some key nutrients, health problems such as iron deficiency (which is linked with long-term neurological damage), and behavioral issues and mental health conditions. These problems, in turn, can lower children’s test scores, their likelihood of graduating from high school, and their earnings in adulthood.

Interventions that provide access to affordable food and reduce food insecurity have been linked to better health for young children as well as long-term improvements in health and longevity; greater high-school completion; and higher earnings and self-sufficiency in adulthood, whether by improving nutrition or reducing harmful stress. For example, a study of the introduction of food stamps (later renamed the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP) found that children from disadvantaged families that had access to food stamps in utero or early childhood had better health outcomes as adults and were more likely to graduate from high school than their peers in counties that had not yet implemented food stamps.

Housing Assistance Can Provide Stability at Home and in School

Loss of housing often causes families with few resources to move into crowded housing with family or friends, to different communities that require their children to change schools, or, for those with the fewest resources, to experience homelessness. Children who live in crowded homes or move frequently have been found to score lower on reading tests, complete less schooling, have difficulty concentrating in school, and experience learning gaps.

Rental assistance can reduce housing instability, overcrowding, and poverty, and in turn may help children avoid the adverse effects these problems have on their health, development, and education. Housing assistance can also prevent homelessness, which leaves children more likely than other low-income children to drop out of school, repeat a grade, or perform poorly on tests.

Income and Other Economic Supports Could Provide Lasting Gains for Next Generation

Evidence links stronger assistance with healthier birthweights, lower maternal stress (measured by reduced stress hormone levels in the bloodstream), better childhood nutrition, higher school enrollment, higher reading and math test scores, higher high school graduation rates, higher rates of college entry, and other benefits.

Particularly compelling evidence comes from a series of cross-program comparisons of several anti-poverty and “welfare-to-work” pilot programs in the United States and Canada in the 1990s. When programs provided more generous income assistance, the comparisons consistently showed better academic performance among young children starting school.

Investing in families and children through income supports benefits society as a whole. Researchers studied the impact of increasing the Child Tax Credit to $3,000 ($3,600 for children younger than 6) and making the full credit available to families with low or no incomes. By boosting the future earnings and tax payments of child beneficiaries, improving the health and longevity of parents and children, and reducing health care, child protection, and criminal justice costs, the Child Tax Credit expansion would likely provide large and lasting gains for the next generation, the researchers project. (See Figure 3.)

Children in Distress Due to Increased Hardship: An Interview With Dr. Philip A. Fisher

Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships

End Notes

[1] The full version of this report is available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/bolstering-family-income-is-essential-to-helping-children-emerge.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise