- Home

- Social Security

- Aid To The Aged, Blind, And Disabled

Policy Basics: Aid to the Aged, Blind, and Disabled

Puerto Rico’s Aid to the Aged, Blind, and Disabled (AABD) program provides valuable aid to low-income adults who are elderly, blind, or disabled, helping them afford basic needs. But its benefits are a fraction of those that Supplemental Security Income (SSI) — itself a very modest cash-assistance program — provides to residents of the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Puerto Rico residents don’t have the same access to federal assistance programs as people in the mainland United States. For instance, key nutrition assistance and health coverage programs exist in limited form in Puerto Rico, providing substantially lesser benefits and services than in the rest of the country due to funding constraints. Moreover, Puerto Rico has yet to recover from a recession that began in 2006, as well as two devastating hurricanes, a historic bankruptcy, powerful earthquakes, and the COVID-19 health and economic crises. As a result, Puerto Rico’s poverty rate of 43.5 percent far exceeds the 10.5 percent average for the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Puerto Rico’s unequal access to federal programs is particularly harmful given the island’s high disability rate. Nearly 1 in 6 Puerto Rican residents (15.1 percent) are disabled, according to the Census Bureau, compared to 8.6 percent of the general U.S. population. This follows the pattern in the states, where disability benefit receipt tends to be higher among populations that are less educated, older, and have fewer immigrants. Moreover, the factors contributing to Puerto Rico’s high poverty rate have disproportionately affected the disabled community. Nearly half of the island’s disabled residents live in poverty — twice the U.S. average.

How Does AABD Differ From SSI?

Federal policymakers created SSI in 1972 to replace the patchwork system of federal grants to states for aid to people who are aged, blind, or disabled. But they did not extend SSI to Puerto Rico, which instead continued to receive matching grants to operate its AABD program. AABD, established in Puerto Rico by the Public Welfare Amendments of 1962, is administered by the Department of Family Socioeconomic Development (Administración de Desarollo Socioeconómico de la Familia, or ADSEF. The federal government funds 75 percent of the program’s benefit costs and 50 percent of its administrative costs.

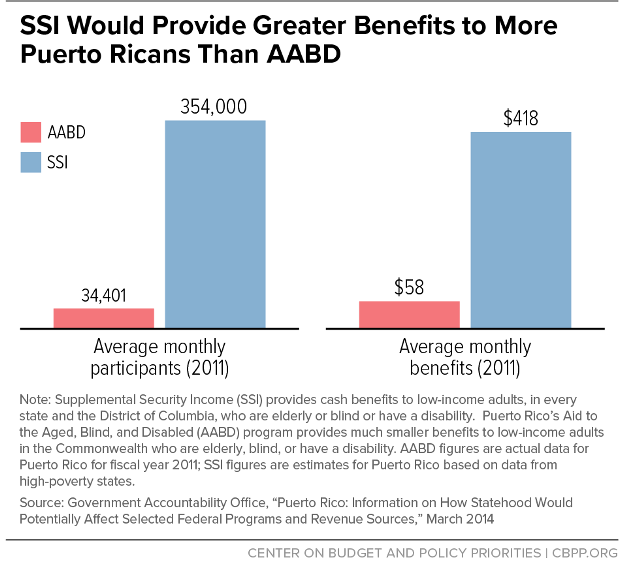

Unlike SSI, which operates as an entitlement — meaning that anyone who meets the eligibility criteria is entitled to draw benefits — the number of AABD beneficiaries is limited by its annual funding. Federal law caps the cumulative funding that Puerto Rico and the other territories receive annually for a variety of adult assistance programs, including AABD. Puerto Rico’s cap is roughly $36 million for adult assistance, foster care, adoption assistance, and AABD; this figure is not indexed to inflation and hasn’t changed since fiscal year 1997. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that in 2011, federal spending on AABD was less than 2 percent of what it would have been if Puerto Ricans received full SSI benefits. GAO also estimated that monthly benefits for an individual, which averaged only $58 under AABD in 2011, would have been $418 under SSI. (See graphic.)

A lawsuit moving through federal courts seeks to extend full SSI benefits to Puerto Rican residents under the Equal Protection guarantee of the Constitution. A U.S. court of appeals ruled in April 2020 that SSI must be fully extended to Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories, but the Trump Administration has appealed the case to the Supreme Court. Extending SSI to Puerto Rico would greatly increase benefits and eligibility, helping hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans at a cost of roughly $2.6 billion a year once fully phased in, according to estimates for 2018 from the Puerto Rico-based Center for a New Economy.

Who Qualifies for AABD and What Benefits Do They Receive?

Puerto Rico’s eligibility standards for AABD are limited by the modest size of the block grant and differ from SSI in some key ways. Notably, children under age 18 are ineligible for AABD but eligible for SSI, which is the only income support for children with disabilities. This difference is particularly notable given Puerto Rico’s high child poverty rate of 57 percent.

AABD’s disability criteria are subtly different from SSI’s. Rather than requiring a recipient to be “suffering from a severe, medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is expected to last 12 months or result in death,” AABD requires a recipient to have a “physical or mental impairment that will likely not improve and which prevents them from performing their previous job or any other paid work.” Thus, people who can do some work — even if not enough to support themselves — or whose disability will likely improve after 12 months are ineligible for AABD.

Similarly, AABD’s asset and income criteria largely follow SSI’s but with a few differences. Under both programs, recipients must have less than $2,000 in assets, including cash, bank accounts, stocks and bonds, life insurance, and farms or other property (but excluding their primary residence and a car). But unlike SSI, AABD does not raise this limit to $3,000 for married couples; this failure creates a higher “marriage penalty” for would-be AABD recipients, since the total asset limit for a couple if both receive AABD is $4,000 if they aren’t married but just $2,000 if they are married.

AABD benefits comprise a “basic benefit” of up to $64 a month and a “secondary benefit” equaling 50 percent of actual shelter costs up to $100 per month. (By comparison, SSI’s maximum federal monthly benefit in 2021 is $794.) Like SSI, AABD reduces benefit amounts for recipients who have other sources of income. Specifically, for people who are aged or have disabilities, both programs exempt (or “disregard”) the first $20 per month of earnings plus one-half of the next $60 per month but then subtract any earnings above that disregard dollar-for-dollar from their benefits. (For people who are blind, the disregard is the first $85 of earnings plus one-half of the next $85.) These rules dramatically limit eligibility for AABD for people with other sources of income, since a person with countable income over $64 a month doesn’t qualify.

Who Participates in AABD and How Much Does the Program Cost?

Roughly 37,000 people participated in AABD in an average month in 2015 (the latest year available) and received benefits averaging $75, including the basic benefit and shelter costs. Some 55 percent of AABD participants are disabled, while 44 percent are seniors and 1 percent are blind.

Federal spending on AABD was $26.5 million in 2015, with $25.2 million for benefit payments and $1.3 million for administrative costs. Based on this data, Puerto Rico’s spending was an estimated $9.7 million, with $8.4 million for benefits and $1.3 million for administration. Thus, combined expenditures were an estimated $36.2 million, with $33.6 million for benefits and $2.6 million for administration.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.