- Home

- Pension Conference Agreement Makes Retir...

Pension Conference Agreement Makes Retirement Tax Cuts Permanent But Fails To Offset Their Cost

The conference agreement on pension legislation would make permanent provisions enacted in the 2001 tax-cut law to expand tax-preferred retirement and education savings accounts. The conference agreement makes these tax cuts permanent without offsetting their cost.

According to Joint Committee on Taxation estimates, making these tax cuts permanent would cost $52.6 billion between 2007 and 2016. Moreover, the bulk of the ten-year cost occurs only in the last six years, because the higher contribution limits to 401(k)s and IRAs — the most costly provisions being extended — do not expire until the end of 2010. Extending these tax cuts would contravene the principle, laid out by former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan among others, that expiring tax cuts should be extended only if offset.

Of particular concern from a fiscal standpoint is that making these 2001 tax cuts permanent without offsetting their cost could initiate a process by which many provisions of the 2001 and 2003 tax-cut legislation (and other expiring tax cuts) are made permanent in a piecemeal fashion over several years. If various tax cuts are each extended separately, less consideration likely will be given to their combined effect on long-term deficits. But making all expiring provisions permanent would add $3.3 trillion to deficits and debt over the next decade.

Rushing to extend the higher contribution limits to tax-preferred retirement savings accounts in advance of their 2010 expiration is particularly troubling for two additional reasons:

-

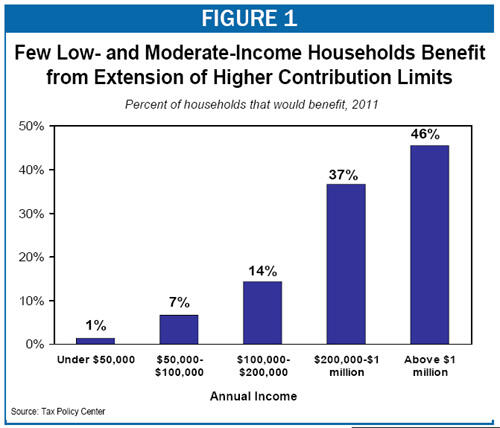

First, these provisions primarily benefit high-income households and provide little or no assistance to low- and moderate-income taxpayers attempting to save for retirement. According to the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, only 6 percent of all households — and only 1 percent of households with incomes below $50,000 — would benefit at all from the extension of these provisions. In contrast, nearly half of the households with incomes above $1 million would benefit (see Figure 1.)

Overall, about three-quarters of the tax benefits would go to taxpayers who have incomes over $100,000 a year. Yet this group accounts for fewer than one sixth of all taxpayers.

-

Second, although the purported goal of raising the contribution limits for tax-preferred savings accounts is to increase personal saving, there is no evidence that the higher contribution limits actually have this effect. The data needed to assess the impact of the 2001 pension tax cuts on saving is not yet available. Moreover, as the Congressional Research Service recently reported, broader research on tax-preferred savings accounts has found that such accounts “appear to be relatively ineffective in inducing new saving,” and that when their effects in increasing the budget deficit are taken into account, “the long-term effect on national savings and economic growth is likely negative.” [1] In acting now to extend the 2001 provisions, Congress would be spending billions of dollars to make these tax cuts permanent without waiting for evidence on their effects, and in the face of evidence that other, similar provisions have proven to be ineffectual.

It should be noted that among the pension-related tax provisions that the conference agreement makes permanent is the saver’s credit. This credit is the sole provision in the 2001 tax-cut law that was intended to boost savings among low- and moderate-income households. In contrast to the provisions that increase the contribution limits for IRAs and 401(k)s — the primary effect of which appears to be to induce high-income households to shift money they already are saving from taxable investment vehicles to tax-preferred retirement accounts — there is evidence that savings incentives targeted to low- and moderate-income households do result in increased saving. The conference agreement also indexes the income limits in the saver’s credit to inflation, thereby addressing a flaw in the credit’s original design. The conference agreement does not, however, index the saver’s credit contribution limits for inflation, so the value of the maximum allowable contribution will erode over time. In contrast, under the conference agreement, both the income and the contribution limits for savings accounts benefiting higher-income households would be indexed for inflation.

For a more detailed discussion of these issues, see Robert Greenstein and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Pension Bill Conference Report May Make Some 2001 Tax Cuts Permanent Without Offsetting Their Costs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 17, 2006 .

End Notes

[1] Thomas Hungerford, “Saving Incentives: What May Work, What May Not,” Congressional Research Service, June 20, 2006.

More from the Authors