- Home

- Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenses For Medic...

Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenses for Medicaid Beneficiaries Are Substantial and Growing

Key Findings

Federal and state officials are discussing possible ways to reduce Medicaid expenditures. One commonly mentioned proposal is to increase the copayments that poor Medicaid beneficiaries must pay when receiving medical care. A related proposal would reduce the benefits that Medicaid covers for some groups.[1] A rationale offered for these changes is that Medicaid policies are outdated and have not kept pace with changes in the private market.[2]

Many assume that because cost-sharing in Medicaid is limited, low-income Medicaid beneficiaries pay almost nothing and bear little financial responsibility for their health care. The analysis presented here shows, however, that the amounts that Medicaid beneficiaries pay out-of-pocket for medical care already are substantial and are growing twice as fast as their incomes. The data also indicate that out-of-pocket expenses have been growing significantly faster for poor adults on Medicaid than for people with private health insurance.

Medicaid policies that further increase cost-sharing significantly or reduce the benefits that Medicaid covers will shift more costs to low-income Medicaid beneficiaries. Such costs are likely to affect access to health care for significant numbers of low-income people. The risks from such policy changes would be most serious to those in the poorest health, since they need the most health care services and thus could face more copayment charges or the loss of more services.

Using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys, we examined the out-of-pocket medical expenses both of poor Medicaid beneficiaries and of people at higher income levels who had private health insurance. (The Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys are a series of nationally representative surveys conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.) The out-of-pocket expenses examined include the amounts that people pay as copayments, deductibles, and coinsurance, as well as the amounts paid for medical services not covered under insurance policies.[3] The key findings are as follows:

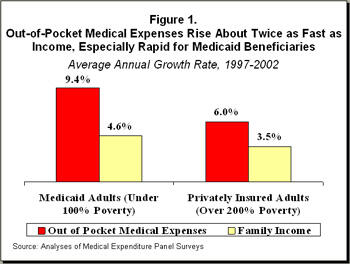

- Out-of-pocket medical expenses for adult Medicaid beneficiaries who are not elderly or disabled and have incomes below the poverty line (about $16,090 for a family of three in 2005) grew by an average of 9.4 percent per year from 1997 to 2002, the most recent year for which these data are available. The out-of-pocket medical expenses of these beneficiaries rose twice as fast as their incomes, which grew 4.6 percent per year.[4]

- Out-of-pocket medical expenses also grew for non-elderly, non-disabled adults who are not low income and have private health insurance, but at a slower pace. For privately insured adults with incomes above 200 percent of the poverty line (more than $32,180 for a family of three), out-of-pocket medical expenses increased an average 6 percent per year from 1997 to 2002.

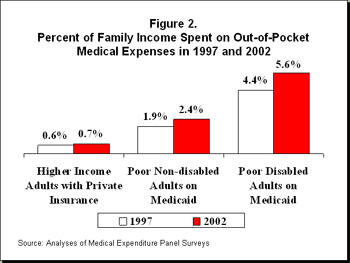

- Expressed as a percentage of income, the out-of-pocket medical expenses that adult Medicaid beneficiaries bear are substantially larger than those borne by non-low-income adults with private insurance. Poor adult Medicaid beneficiaries spent 2.4 percent of their incomes on out-of-pocket medical expenses in 2002. Privately insured adults with incomes exceeding twice the poverty line spent 0.7 percent of their incomes. ("Adult" as used here and later in this paper refers to adults who are not elderly or disabled, except as otherwise noted.)

- People with serious health problems bear heavier burdens. Out-of-pocket medical expenses were especially high for poor disabled Medicaid beneficiaries, consuming an average of 5.6 percent of the incomes of these beneficiaries in 2002.

- Out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs have been rising especially rapidly. Between 1997 and 2002, out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs rose 14 percent per year for adult Medicaid beneficiaries who are not elderly or disabled, 17 percent per year for adult Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities, and 10 percent per year for people with private insurance.

Increases in Medicaid Cost-sharing in Recent Years

Because Medicaid is designed to make health care coverage affordable for low-income people, it limits cost-sharing charges and does not impose cost sharing on vulnerable populations such as children and pregnant women. Within the permissible limits, increases in Medicaid copayments — as well as reductions in the scope of the health care services that Medicaid covers — have been common in recent years.

- According to the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, four states raised Medicaid copayments in 2002, seventeen states increased them in 2003, twenty states raised them in 2004, and nine states plan to do so in 2005.

- Similarly, nine states reduced the scope of Medicaid benefits in 2002, eighteen states lowered benefit coverage in 2003, nineteen states did so in 2004, and nine states plan restrictions in 2005.[5] Examples of Medicaid benefit reductions include: ending dental or vision care for adults, reducing the number of prescription drugs covered in a month, reducing the number of physician visits authorized in a year, or limiting coverage of medical equipment, such as crutches.

- Both copayment increases and benefit reductions affect out-of-pocket expenses. For example, if the Medicaid copayment for a prescription rises from $1 to $3, the expenses of a person who uses five prescriptions a month would rise from $60 per year to $180 per year. If a state Medicaid program stops offering dental care for adults, a Medicaid beneficiary must pay the full price for dental care, unless he or she can find a dentist who offers free or reduced price services. If a state reduces the authorized number of prescriptions from six per month to five, a person who needs six medications must pay out-of-pocket for the sixth prescription or do without. Since those who are in poorer health are more likely to use multiple medications and need more health care services, they are more likely to be harmed by higher copayments and benefit reductions.

Medical research has consistently shown that cost-sharing has more serious consequences for low-income people than for those with higher incomes. Higher copayments cause some low-income people to forgo health care services, including essential services, which can lead to costly consequences such as increases in emergency room care. Higher copayments also can impair the health of low-income beneficiaries who forgo necessary medical care because of the cost.[6]

How Much Do Medicaid Beneficiaries Pay?

Many people mistakenly assume that Medicaid beneficiaries pay almost nothing for their health care. Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys show, however, that poor adult Medicaid beneficiaries paid an average of $210 in 2002 for out-of-pocket medical expenses.[7] Non-low-income adults with private insurance paid an average of $548. Because the average income of a poor adult Medicaid beneficiary is about one-ninth the average income of privately insured adults who are not low income, Medicaid beneficiaries pay substantially more as a share of income than middle- and upper-income people do. Moreover, because poor people have far less discretionary income (after paying for basic needs like food and rent) than people with higher incomes, the effective burden that out-of-pocket medical expenses impose is greater for people on Medicaid than these statistics portray.

We also analyzed the out-of-pocket expenses of disabled Medicaid beneficiaries who receive Supplemental Security Income benefits and have incomes below the poverty line.[8] Disabled SSI beneficiaries on Medicaid bear heavier out-of-pocket costs. Due to their more serious health problems, they require more health care and incur greater expenses, including more copayments. In 2002, poor disabled SSI beneficiaries covered by Medicaid spent an average of 5.6 percent of their incomes on out-of-pocket medical expenses, more than twice the percentage of income that non-disabled adult Medicaid beneficiaries paid, and about eight times the percentage of income paid by non-low-income adults with private insurance.

When Medicaid imposes cost-sharing, people with disabilities and those with chronic health problems tend to bear the highest burdens.[9] Restrictions on the needed services that Medicaid covers also have a disproportionate impact on those who have more serious health problems.

| Changes in Average Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenses for Poor Adults on Medicaid and higher-income Adults with Private Health Insurance, 1997 to 2002 | |||

|

| 1997 | 2002 | Average Annual Growth, 1997-2002 |

| Non-Disabled Medicaid Adults with Incomes Below Poverty |

|

| |

| Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenses |

|

|

|

| Total | $134 | $210 | 9.4% |

| Prescription drugs | $62 | $120 | 14.1% |

| Other Services | $72 | $90 | 4.5% |

| Family Income | $7,071 | $8,846 | 4.6% |

| Out-of-Pocket Expenses as Percent of Income | 1.9% | 2.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Disabled SSI Medicaid Adults with Incomes Below Poverty Line |

|

| |

| Out-of-Pocket Expenses |

|

|

|

| Total | $323 | $441 | 6.4% |

| Prescription Drugs | $141 | $308 | 16.9% |

| Other Services | $182 | $133 | -6.1% |

| Family Income | $7,265 | $7,819 | 1.5% |

| Out-of-Pocket Expenses as Percent of Income | 4.4% | 5.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Privately-Insured Adults with Incomes Over 200 Percent of Poverty |

| ||

| Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenses |

|

|

|

| Total | $409 | $548 | 6.0% |

| Prescription Drugs | $105 | $173 | 10.4% |

| Other Services | $304 | $375 | 4.3% |

| Family Income | $67,747 | $80,325 | 3.5% |

| Out-of-Pocket Expenses as Percent of Income | 0.6% | 0.7% |

|

| Note: Analyses of Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys for adults 19 to 64 years old. Out-of-pocket medical expenses include deductibles, copayments, and expenses not reimbursed by insurance. Insurance coverage determined by source of coverage for the majority of the year. | |||

Conclusion

Contrary to common assumptions, the out-of-pocket medical expenses that Medicaid beneficiaries pay are significant, and they have been growing rapidly in recent years. Proposals to increase Medicaid cost-sharing significantly or to reduce the scope of covered benefits could accentuate these problems and create larger burdens for poor Medicaid beneficiaries, making it harder for many to access needed care. The consequences could be especially harsh for people who have disabilities or other serious health problems.

Technical Notes

These data are based on the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys (MEPS), a series of nationally representative surveys conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. We focused on out-of-pocket medical expenses by non-elderly adults (19 to 64 years old) and compared adults on Medicaid who have incomes below the poverty line[10] to those who have private health insurance and have incomes greater than 200 percent of the poverty line. Out-of-pocket medical expenses include cost-sharing amounts, such as copayments, deductibles or coinsurance, as well as medical expenses not covered by insurance. Consumers’ payments for monthly health insurance premiums are not included as out-of-pocket medical expenses, nor are payments for over-the-counter medications. In MEPS, we cannot distinguish between cost-sharing amounts and uncovered medical expenses.

To define those who were on Medicaid or private insurance, we selected individuals who were covered by either type of insurance for a majority of the year, seven months or longer. As a check, we replicated the 1997 and 2002 analyses using a stricter criterion of coverage for all 12 months of the year and produced equivalent results. Using a full-year criterion, out-of-pocket medical expenses for poor non-disabled adult Medicaid recipients rose an average of 10.2 percent per year from 1997 to 2002, and out-of-pocket medical expenses comprised 1.7 percent of this group’s income in 1997 and 2.2 percent in 2002. Results for the privately-insured and those on SSI also were consistent using either a majority-of-year or full-year criterion. Thus, the trends reported here are not materially affected by medical expenses that are incurred in months when a person is not covered by Medicaid or private insurance. We base insurance coverage on the majority of a year because it increases sample size and increases the stability of estimates.

We also examined data from the 1999 MEPS and found patterns consistent with those observed in 1997 and 2002. For example, poor Medicaid beneficiaries spent a larger percentage of their incomes on out-of-pocket medical expenses than did non-low-income privately-insured people in 1999, just as was true in 1997 and 2002. We did not include these data for the sake of brevity.

End Notes

[1] Robert Tanner, “U.S. Governors Consider Medicaid Reform: U.S. Governors May Have Poor Pay Larger Share of Health Care Bills as Part of Medicaid Reform,” AP story carried in ABCNews.com, April 24, 2005. Robert Pear, “States Proposing Sweeping Change to Trim Medicaid,” New York Times, May 9, 2005.

[2] For example, see Vern Smith and Greg Moody, “Medicaid in 2005: Principles and Proposals for Reform,” Health Management Associates, report prepared for the National Governors Association, Feb. 2005.

[3] The survey does not include data on the amounts paid as monthly insurance premiums.

[4] This report focuses on adults because children are generally exempt from Medicaid cost-sharing under federal law. The people subject to Medicaid copayments are primarily adults. Federal law also exempts pregnant women and people who are institutionalized (e.g., in nursing homes) from copayments.

[5] Vernon Smith, et al. “The Continuing Medicaid Budget Challenge: State Medicaid Spending Growth and Cost Containment in Fiscal Years 2004 and 2005,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Oct. 2004.

[6] This body of research is summarized in Leighton Ku, “The Effect of Increased Cost-sharing in Medicaid: A Review of the Research,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 2005.

[7] The MEPS data do not distinguish copayments or other cost-sharing from expenses for medical care not covered by insurance. The average $210 in out-of-pocket expenses paid by Medicaid beneficiaries includes both types of expenses.

[8] Our main analyses contrast the expenses of non-disabled adult beneficiaries and those who are privately insured in order to make the groups more comparable. A person with permanent disabilities is much less likely to be on private insurance than on Medicaid and has much higher expenses.

[9] Bruce Stuart and Christopher Zacker, “Who Bears the Burden of Medicaid Drug Copayment Policies?” Health Affairs, 18(2):201-12, 1999

[10] Most adult Medicaid beneficiaries have incomes below the poverty line. The majority of adult beneficiaries with incomes above poverty are pregnant women who are generally exempt from copayments under Medicaid.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: