Elementary and high schools are receiving less state funding than last year in at least 37 states, and in at least 30 states school funding now stands below 2008 levels – often far below. These cuts are attributable, in part, to the failure of the federal government to extend emergency fiscal aid to states and school districts and the failure of most states to enact needed revenue increases and instead to balance their budgets solely through spending cuts. The cuts have significant consequences, both now and in the future: They are causing immediate public- and private-sector job loss, and in the long term are likely to reduce student achievement and economic growth.

Our review of budget documents finds that, of 46 states that publish education budget data in a way that allows historic comparisons:

- 37 states are providing less funding per student to local school districts in the new school year than they provided last year.

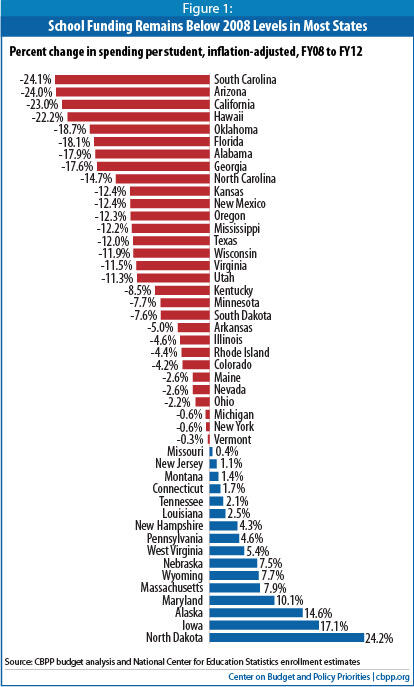

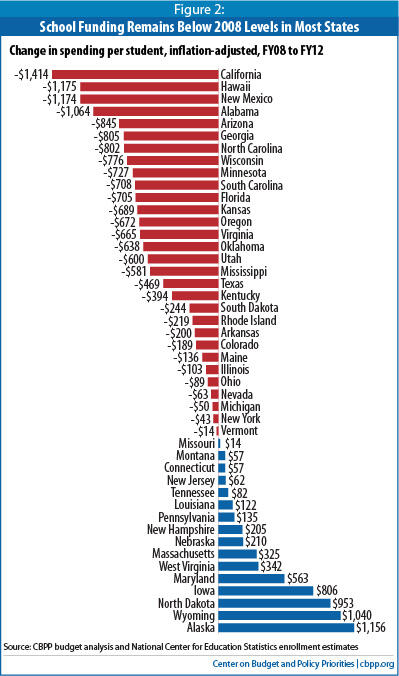

- 30 states are providing less than they did four years ago..

- 17 states have cut per-student funding by more than 10 percent from pre-recession levels.

- Four states— South Carolina, Arizona, California, and Hawaii — each have reduced per student funding to K-12 schools by more than 20 percent. (These figures, like all the comparisons in this paper, are in inflation-adjusted dollars and focus on the primary form of state aid to local schools.)

State-level K-12 spending cuts of this magnitude have serious consequences for the nation.

- State-level K-12 cuts have large consequences for local school districts. Some 47 percent of total education expenditures in the U.S. come from state funds (the share varies by state). Cuts at the state level mean that local school districts have to either scale back the educational services they provide, raise more revenue to cover the gap, or both. In particular, cuts in state aid may particularly affect school districts with high concentrations of children in poverty. States typically distribute general education aid through formulas that target additional funds to school districts with large shares of low-income and other high-need children and/or with lower levels of taxable wealth. As a result, reductions in "formula" funding may result in particularly deep cuts in general state aid for less-wealthy, higher-need districts unless a state goes out of its way to protect them.

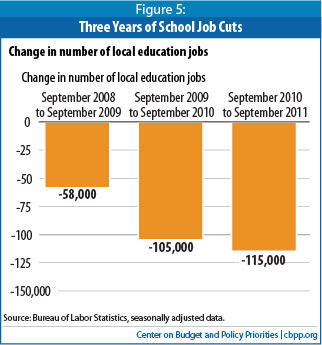

- The cuts have extended the recession and slowed the recovery. Federal employment data show that school districts began reducing the overall number of teachers and other employees in September 2008, when the first round of budget cuts began taking effect. The job losses have accelerated in the last year as the cuts have deepened; by September 2011, local school districts had cut 278,000 jobs nationally compared with 2008. These job losses have reduced the purchasing power of workers’ families, in turn reducing overall consumption in the economy and thus extending the recession and slowing the pace of recovery.

- A further negative economic consequence of the cuts is that they counteract and sometimes undermine education reform and more generally hinder the ability of school districts to deliver high-quality education, with long-term negative consequences for the nation's economic competitiveness. Many states and school districts have undertaken important school reform initiatives to prepare children better for the future, but deep funding cuts hamper their ability to implement many of these reforms, particularly in areas like teacher training and early childhood education. At a time when the nation is trying to produce workers with the skills to master new technologies and adapt to the complexities of a global economy, large cuts in funding for basic education threaten to undermine a crucial building block for future prosperity.

- Local school districts typically have little ability to replace lost state aid on their own. Given the sorry state of many of the nation's real estate markets, it is difficult for many school districts to raise more money from the property tax without raising rates, and rate increases are often politically very difficult. As a result, property tax and other local revenues were actually lower in the 12- month period ending in June 2011 than they were the previous year. However, at least some localities are considering and in some cases enacting property tax increases — a sign of the challenges that schools face.

State and federal aid are major sources of funding for K-12 schools. On average, some 47 percent of total education expenditures in the U.S. come from state funds; the share varies by state. States typically distribute most of this funding through formulas that allocate money to school districts, with some funds often targeted to districts that have higher levels of student need (e.g. more students from low-income families) and less ability to raise funds from local property taxes and other local revenues.

Another important source of funds is federal aid. With state budgets under extreme pressure since the 2007-09 recession, the federal government has provided emergency education aid to states. Under the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund established by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009, states received $39 billion in federal aid targeted at K-12 and higher education funding. And through the Education Jobs Fund enacted by Congress in August 2010, states received an additional $10 billion in federal aid aimed at saving education jobs in schools, colleges, and universities.

States distributed most of the portion of this funding that went to K-12 school districts using the same formulas they normally use to distribute state education funding. Indeed, both ARRA and the Education Jobs Fund generally required states to distribute the funding in this way. [1]

Both ARRA and the Education Jobs Fund required states to maintain their K-12 education spending at certain levels, to assure that the federal aid was used as intended to help states sustain their education systems during the recession.[2]

ARRA also provided states with much more narrowly targeted forms of federal education aid. For example, ARRA provided $13 billion in targeted, additional aid for schools with a large share of low-income students (Title I schools), and $12 billion in aid targeted to help schools sustain education programs for disabled students. These funds are targeted to particular student populations and hence typically are not distributed through the funding formulas used to distribute general state aid.

Cuts to state formula funding often have very large consequences for local school districts. Cuts at the state level mean that local school districts have to either scale back the educational services they provide, raise more revenue to cover the gap, or both. In addition to the funding distributed through general aid formulas, states may or may not use separate allocations to fund items such as pupil transportation, contributions to school employee pension plans, and teacher training; some of those allocations also have been cut.

Moreover, since states typically distribute general education aid through formulas that target additional funds to school districts with large shares of low-income and other high-need children, reductions in "formula" funding may result in particularly deep cuts in general state aid for districts with high concentrations of low-income students. ARRA's additional federal aid for Title I schools and for schools serving disabled students helped soften the blow of the recession on the children in these schools. But with the federal aid now expiring, reductions in state formula funding may be pulling in the opposite direction by reducing funding disproportionately for districts with high concentrations of low-income students. (A number of states, such as New Jersey, are under court order to avoid cuts that hurt high-poverty districts, in which case middle-income districts may be hit harder.)

For 46 states, the necessary data are available to compare state K-12 formula funding in the current school year with funding in earlier years. [3] (The other four states – Delaware, Idaho, Indiana, and Washington State – publish education funding data in ways that make it difficult to make accurate historical comparisons). The 46 states included in this analysis are home to 95 percent of the nation's schoolchildren.

Based on the data available in these 46 states, cuts to state education formula funding since the start of the recession have been widespread and very deep. This survey finds that, after adjusting for inflation:

- Almost two-thirds of states — 30 of the 46 states surveyed — are providing less per-student funding for K-12 education in the current 2012 fiscal year than they did in fiscal year 2008.

- In well over one-third or 17 of the 46 states, per student funding is 10 percent or more below pre-recession levels.

- The four states with the deepest cuts —Arizona, California, Hawaii and South Carolina — each are reducing per student funding by more than 20 percent from pre-recession levels.

While most states are cutting spending on education, as the figures in this analysis show, a few states are boosting it. A few states such as Alaska, Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming have significant oil and gas revenues and therefore have not suffered the same level of economic problems as other states, and thus they have enacted fewer budget cuts. In other states, the growth in spending reflects policymakers' prioritization of education funding in the face of fiscal stress. For example, Maryland was already embarking on a program of increased state aid for local school districts when the recession hit, and chose largely to maintain that program. Massachusetts' and Iowa's spending growth reflects lawmakers' decisions to maintain education funding even as these states cut programs in other areas. Maryland and Massachusetts also raised significant amounts of revenue after the onset of the recession, which lessened the need to scale back education funding.

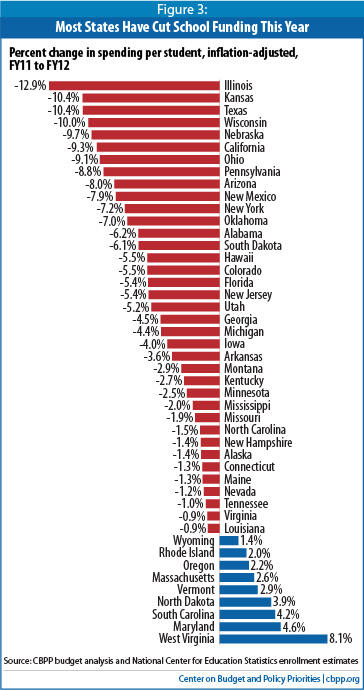

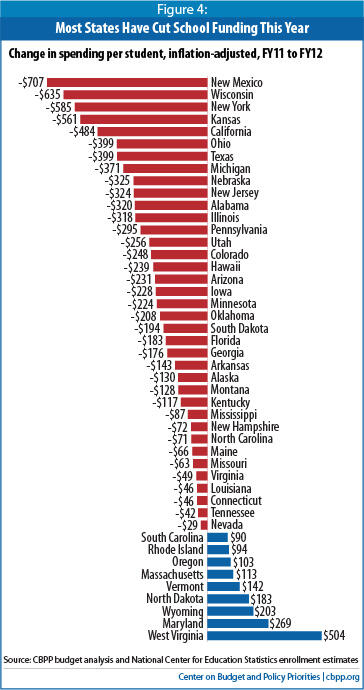

Some of the deepest reductions to K-12 formula funding since the onset of the recession have occurred in the past year, as federal aid intended to sustain state education spending has expired, rainy day funds have been exhausted, and states have resisted raising additional taxes to offset the need for cuts. After adjusting for inflation between last year (fiscal year 2011) and the current 2012 fiscal year:

- The great majority of states — 37 of the 46 states for which data are available — have cut per student education funding.

- At least 27 states have cut per student funding by more than two percent.

- At least 19 states have cut per student funding by more than five percent.

- Four states -- Illinois, Kansas, Texas, and Wisconsin – have cut spending by 10 percent or more since last year.

These cuts are occurring at a time when schools face demands from parents, employers and civic leaders to bring more and more students to higher levels of academic proficiency, in large part because workers will increasingly need higher levels of educational attainment to thrive in the workforce.

It is not just K-12 education that is being cut. States are cutting funding for higher education, for health care, for human services, and a range of other areas of spending.[4] States have enacted these cuts primarily because the recession caused state revenue to decline sharply as costs increased. In addition, the federal government has not offered additional emergency fiscal aid and few states raised new revenue this year.

- Revenues remain depressed. The recession of 2007-09 and the slow recovery continue to affect state budgets and schools. With unemployment still high and housing values still depressed, people have both less income and purchasing power. So states are receiving less income and sales tax revenue, which are the main sources of revenue states use to fund education and other services. Roughly three out of four states project that they will have less state revenue in 2012 (after adjusting for inflation) than they did in fiscal year 2008, when the recession began. States on average balanced their budgets based on fiscal year 2012 revenue projections that were seven percent lower than before the recession, after adjusting for inflation.[5] While state revenues are starting to improve across the country, the rate of growth is generally not nearly sufficient to make up for multiple years of revenue loss.

- Costs are rising. The cost of meeting people's needs has increased since the recession began, due to inflation, demographic changes and to the recession. For example, in the current school year, the U.S. Department of Education estimates that there are about 260,000 more K-12 students and another 1.5 million more public college and university students than there were in 2007-08, for example. [6] Some 5.6 million more people are projected to be eligible for subsidized health insurance through Medicaid in 2012 than were enrolled in 2008, as employers have cancelled their coverage and people have lost jobs and wages. [7]

- Few states raised new revenue this year. States could have minimized the cuts to education this year by balancing their budget with a combination of cuts and revenue increases, rather than just cutting. But while more than 30 states raised revenue to help close their budget shortfalls earlier in the recession, this year few states raised new revenue. Most depended entirely on spending cuts to resolve their budget problems for the current year, and in fact several states allowed previously enacted tax increases to lapse and/or enacted new tax cuts, worsening the budget problems. [8]

- Emergency federal aid is mostly depleted. States used emergency fiscal relief from the federal government (including both education aid and other forms of state fiscal relief) to cover about one-third of their budget shortfalls through the 2011 fiscal year, which ended on June 30 in most states. Only about $6.7 billion in fiscal relief remains for the current 2012 fiscal year, a year in which states faced shortfalls totaling at least $103 billion. That is, the remaining fiscal relief covers less than seven percent of state budget shortfalls for the fiscal year that just began.

Nearly all the aid remaining is explicitly targeted to education, but it is mostly depleted. Based on U.S. Department of Education data, entering the current school year only about $2 billion of the $39 billion in education aid under ARRA's State Fiscal Stabilization Fund remained available for school districts to spend, and only about $4 billion of the $10 billion from the Education Jobs Fund remained. [9] In total, then, only about $6 billion or roughly 13 percent of the federal aid targeted explicitly to supporting general state education funding remains.[10] Since this education aid is intended to help states sustain both their K-12 systems and their higher education institutions, not all of the remaining education funds will go to K-12 schools.

Not only is emergency federal aid largely depleted, federal policymakers are planning to make state budget problems worse by cutting the amount of ongoing federal funding to states. The recent debt limit deal likely will lead to over $400 billion in cuts in "non-security discretionary" funding over the next decade. Fully one-third of this category of federal spending flows through state governments in the form of funding for education, health care, human services, law enforcement, infrastructure, and other services that states and localities administer. Large cuts in federal funding to states would force states to make still deeper cuts in their budgets.[11]

Congress could spare aid to states while taking all the required savings from purely federal areas of spending, like the FBI and the National Institutes for Health. But that's extremely unlikely, since the resulting cuts in those areas would be prohibitively large.

Federal aid to states will be cut even more, starting in 2013, if the 12-member Congressional committee charged with recommending further deficit reduction measures targets such programs, or if the committee's efforts fall short of the statutorily required levels of deficit reduction and thus lead to automatic reductions in federal appropriations including aid to states.

States' large cuts in spending on education have serious consequences for the economy, both in the short and long term. Not only do they directly impact jobs, but they also counteract and sometimes undermine important state education reform initiatives, and put upward pressure on local property taxes.

State education budget cuts are deepening the recession and slowed the pace of economic recovery by reducing overall economic activity. The spending cuts have forced school districts to lay off teachers and other employees, reduce pay for the education workers who remain, and cancel contracts with suppliers and other businesses. All of these steps remove consumer demand from the economy, which in turn discourages businesses from making new investments and hiring.

Local school districts already have eliminated 278,000 jobs nationally since September 2008, federal data show. In addition, education spending cuts have cost an unknown but probably very large number of additional jobs in the private sector as school districts cancel or scale back private-sector purchases and contracts (for instance, purchasing fewer textbooks). These job losses shrink the purchasing power of workers’ families, which in turn affects local businesses and slows recovery. While it is not possible to calculate directly the additional loss of jobs resulting from state education budget cuts, it appears very likely that school districts will continue to cut jobs and also to cut funding for some private-sector jobs, negating some of the job growth that otherwise would occur in the economy as a whole.

The just-ended school year was the worst yet for school district layoffs, with a net reduction in local education employment (mostly K-12) totaling 115,000 nationally — more than triple the total in the previous year (Figure 5). (Normally, local education employment grows each year in large part to keep pace with an expanding student population.) The spending cuts described in this paper are likely to cause additional job losses throughout the current school year.

[12]In the long term the savings from today's cuts may cost states much more in diminished economic growth. To prosper, businesses require a well-educated workforce. The deep education spending cuts states have enacted will weaken that workforce in the future by diminishing the quality of elementary and high schools. At a time when the nation is trying to produce workers with the skills to master new technologies and adapt to the complexities of a global economy, large cuts in funding for basic education undermine a crucial building block for future prosperity.

State education cuts are counteracting and sometimes undermining reform initiatives that many states are undertaking with the federal government's encouragement, such as supporting professional development to improve teacher quality, improving interventions for young children to heighten school readiness, and turning around the lowest-achieving schools, to name just a few. As U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has said, "It is very difficult to improve the quality of education while losing teachers, raising class size, and eliminating after school and summer school programs." [13]

Some education reforms have moved forward despite reductions in state education funding, in part because ARRA required states to agree to certain reforms before they could receive the aid provided through the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund,[14] and because ARRA offered additional funds to help states innovate through the competitive "Race to the Top" program.

But deep cuts in state spending on education counteract and sometimes undermine reform initiatives both by limiting the funds generally available to improve schools, and by cutting specific reform initiatives. For example:

- Research suggests that teacher quality is the most important school-based determinant of student success, and it is a major emphasis of the "Race to the Top" program. [15] For that reason recruiting, developing, and retaining high-quality teachers is widely thought to be critical to improving student achievement. But these tasks are more difficult when school districts are cutting their budgets. Since teacher salaries make up a large share of public education expenditures, funding cuts inevitably restrict districts' ability to expand teaching staffs and supplement wages. Indeed, numerous school districts have reduced teacher wages through furloughs since the start of the recession and have resorted to hiring freezes. Teacher training has also suffered; for example, the state of Washington as well as a number of school districts in other states have cut funding for professional development.

- There is evidence to suggest that smaller class sizes can boost achievement, especially in the early grades. Yet small class sizes are difficult to sustain when schools are cutting teaching positions while enrollments increase. [16] Indeed, a survey of school administrators found that 57 percent of respondents increased class sizes for the 2010-11 school year, and 65 percent anticipate doing so for the 2011-12 school year. [17]

- Many education policy experts believe that more student learning time can improve achievement. [18] In a number of states and school districts, however, budget cuts are making it more difficult to extend instructional opportunities. For example, funding cuts in Georgia will mean shortening the pre-kindergarten school year from 180 to 160 days for 86,000 four-year- olds. New Jersey's funding cut for afterschool programs will limit structured learning time, and in a 2009 survey of California parents, 41 percent of respondents reported that their child's school was cutting summer programs.[19]

Moreover, reductions in the education workforce make it less likely that schools will have adequate personnel to teach and supervise students for additional periods of time or to give additional attention to students who are having difficulty learning, despite state and federal goals to lessen disparities among achievement levels. Cuts that limit student learning time are likely to intensify in the coming year. The school administrators' survey mentioned above found that 17 percent of respondents were considering shortening the school week to four days for the 2011-12 school year and 40 percent were considering eliminating summer school programs.[20] - As of the 2009-10 school year, 40 states provided pre-kindergarten or pre-school programs, serving 1.3 million children.[21] A number of studies conclude that such programs can improve cognitive skills, especi ally for disadvantaged children.[22] Since the start of the recession, however, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Texas and other states have cut funding from early education programs to help close their budget shortfalls. This year, Texas eliminated state grants for pre-K expansion programs that serve around 100,000 mostly at-risk children, or more than 40 percent of the state's pre-kindergarten students.

Impact on Property Taxes and Other Local Revenues

State budget cuts are also placing upward pressure on property taxes and other local revenues, because increasing these revenues is one of the few ways school districts can compensate for the loss of state funding.

Given the precipitous decline in property values since the start of the recession and in many places the political and/or legal difficulty of raising property taxes, raising significant additional revenue through the property tax will likely be very difficult for school districts in the coming years. Indeed, property tax collections were lower in the 12-month period ending in June 2011 than in the previous 12 months. [23]

Despite the obstacles to raising local revenues, however, there are at least a few districts that are considering, or implementing property tax increases. For example, the Granite School District and the Davis School District, two of the three largest school districts in Utah, recently raised property tax rates by six percent and nine percent respectively to compensate for cuts in state funding and growing enrollments. [24] The city of Chicago is raising property taxes to the maximum allowed by law to fund city schools, in part in response to cuts in state education funding.[25] The Eagle County School District in Colorado will ask voters to approve a $6 million increase in property taxes, in part to make up for declines in state aid, this coming November. [26]

Beyond increasing local revenues, school districts' options for preserving education services are very limited. Some localities could divert funds from other local services to shore up school district budgets. But this would sustain education spending at the expense of services like police and fire protection.

The education funding totals presented in this paper reflect the funding distributed through states' major education funding formulas. These funds include the federal funds distributed through these formulas from ARRA's State Fiscal Stabilization Fund and the Education Jobs Fund. In a few cases, the funding totals also include more narrowly targeted forms of federal education aid in ARRA such as Title I funding.

In cases where we had sufficient data, we attributed federal funds to the year in which they were used by school districts. In other cases, we attributed this aid to the year in which it was distributed to school districts by the state.

The numbers do not include any local property tax revenue or any other source of local funding.

Additional adjustments were made to reflect the following state-specific policies or data limitations:

- California's numbers reflect General Fund Proposition 98 spending for K-12 education and exclude child care funding which was removed from Proposition 98 spending in FY2012.

- Hawaii's numbers do not include federal Education Jobs Fund money. Hawaii operates a single statewide school district with essentially no local funding.

- Maryland's numbers include funding for the state's foundation program as well as funding for compensatory education, aid for local employee fringe benefits, formula programs for specific populations, and limited English proficiency programs.

- Minnesota has withheld (or delayed) $2.2 billion in payments to school districts, reducing the amount of state formula aid provided to districts in fiscal year 2010, 2011 and 2012. The state is expected to reimburse school districts for these withheld payments in the future, but no specific repayment plan has been set forth, so we did not include those withheld/delayed funds in our totals Minnesota's numbers represent formula funding for a dozen or so different programs including special education, compensatory aid (to help schools with high concentration of low-income children), Limited English Proficiency aid, operating capital, etc.

- In Nebraska, $58.6 million in Education Jobs Federal aid was accepted by the state and distributed to the school districts through the state's funding formula in fiscal year 2011. The school districts were encouraged to carry these amounts forward for use in 2012, and there is evidence that school districts generally did so. For this reason, we have counted the entire amount as 2012 spending.

- New York's numbers reflect school districts' fiscal years (which end June 30), rather than the state's fiscal year (which ends March 31).

- Ohio's numbers include line items for state and stimulus funded foundation funding, as well as school district property tax replacement funds that are also considered to be part of the school funding formula.

- South Carolina's numbers do not include federal aid.

- South Dakota received federal Education Jobs funds in fiscal year 2011 but also passed legislation to encumber an equivalent amount ($29.3 million), of already appropriated state funds, requiring that amount to be held over for use in 2012 rather than 2011. For this reason, we have subtracted that amount from 2011 budgeted expenditures and added it to 2012.

- Wisconsin's numbers include aid to high-poverty districts.