- Home

- Losing Out: States Are Cutting 1.2 To 1....

Losing Out: States Are Cutting 1.2 to 1.6 Million Low-Income People from Medicaid, SCHIP and Other State Health Insurance Programs

Summary

States have been in the midst of the most severe state budget crisis in recent memory. This past year, state legislatures adopted changes to close state budget gaps totaling $78 billion for state fiscal year 2004.

Driven by flagging revenues and deep budget deficits, states reduced expenditures in Medicaid and other health insurance programs, such as the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). Actions related to these programs taken by states include cuts in eligibility (or reductions in caseloads through other approaches), freezes or reductions in payment rates to health care providers, prescription drug cost containment, reductions in the health services that are covered, and increases in co-payments or other cost-sharing by low-income patients.

This analysis examines policies that were implemented last year (state fiscal year 2003) or are being implemented this year (state fiscal year 2004) and that cause low-income children or adults to lose health insurance coverage. These policies are reducing the number of low-income people enrolled in public health insurance programs such as Medicaid, SCHIP or similar state-funded health programs (like MinnesotaCare or Washington’s Basic Health program) by 1.2 to 1.6 million.

Almost half of those losing health insurance coverage (490,000 to 650,000 people) are children. Substantial numbers of low-income parents, seniors, people with disabilities, childless adults and immigrants also are losing coverage. Cutbacks of this depth in health insurance coverage for low-income families and individuals are unprecedented.

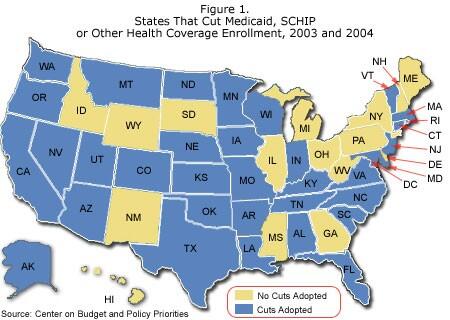

Thirty-four states, in every region of the country, have adopted cuts that are causing low-income families and individuals to lose health insurance. Two states that illustrate the types of cuts taken are:

- Texas . The LoneStarState has adopted deep cutbacks in its SCHIP program that will cause about 160,000 children — one-third of its total SCHIP caseload — to lose coverage. In addition, when children are enrolled in SCHIP, they now must wait three months until they can use medical services. The state also has lowered the income eligibility limit for pregnant women in Medicaid (making more women ineligible for prenatal care and delivery), eliminated its “medically needy” program (which serves people who have gross incomes modestly above the regular Medicaid income limit but also have substantial medical costs that reduce their disposable income below the income limit) and eliminated Medicaid coverage for TANF beneficiaries who have been sanctioned. These changes are causing about 34,000 adults to lose coverage. Finally, the state postponed adopting 12-month “continuous eligibility” for children in Medicaid and adopted measures to increase other application barriers; these steps could cause 150,000 to 300,000 fewer children to be served than would otherwise have been the case. All told, Texas is eliminating coverage for between 344,000 and 494,000 children and adults. Census data showed that, even before these changes, the percentage of people who were uninsured was higher in Texas than in any other state.

- Florida . The state has stopped enrolling children in the state’s SCHIP program. As of early December, there were about 71,000 eligible children on the waiting list (about 44,000 are children on the waiting list due to a general freeze on SCHIP enrollment imposed in July 2003, while the rest are immigrant and other children who are on a similar waiting list due to a more targeted freeze imposed earlier). Last year, the state reduced the Medicaid income eligibility limit for aged and disabled beneficiaries, terminating coverage for about 3,400 people.

States have used different policy approaches to reduce enrollment in the health care programs. Some states have scaled back the Medicaid or SCHIP eligibility criteria. Other states have adopted policies that do not directly limit eligibility but nonetheless result in lower enrollment among eligible people by making it more difficult for eligible people to enroll or to remain enrolled. While such policies are less overt, they, too, cause needy individuals to lose coverage. The types of policies being adopted by various states that cause low-income individuals to lose or be denied coverage include:

- Direct Eligibility Cuts. A number of states reduced Medicaid or SCHIP eligibility limits. For example, Missouri eliminated Medicaid coverage for parents whose incomes fall between 77 percent and 100 percent of the poverty line (between $11,750 for a family of three and $15,260). Connecticut reduced income limits for parents with incomes between 100 and 150 percent of the poverty line (between $15,260 and $22,890 for a family of three). Texas lowered the Medicaid income limit for pregnant women from 185 percent to 158 percent of the poverty line. Alaska reduced the eligibility limit for children in SCHIP from 200 percent of the poverty line to 175 percent and froze the limit so it will not keep pace with inflation in the future (and thus will fall below 175 percent of the poverty line in future years). Oklahoma, Oregon and Texas eliminated their Medicaid “medically needy” programs. Nebraska and North Carolina cut back health coverage for people who have worked their way off welfare by scaling back transitional Medicaid coverage from 24 months after leaving welfare for employment to 12 months.

- Increased Enrollment Barriers. Many states have adopted policies that make it more difficult for applicants to enroll in Medicaid or SCHIP or harder to stay enrolled once admitted. In many cases, these changes cancelled policies that had been adopted to simplify the enrollment process and make the programs more consumer-friendly, especially for working poor families. For example, several states — Arizona, Connecticut, Indiana, Nebraska and Texas — rescinded policies that enroll children for 12-month periods and now instead require reapplications or reviews at least every six months. California, Minnesota and Washington made similar changes with regard to families or parents.

- Higher Monthly Premiums . Several states instituted or increased monthly premiums that participants in SCHIP, state-funded health insurance programs, or selected categories of Medicaid must pay. Research has found that when premiums are imposed or increased, participation by low-income beneficiaries falls. In many states, an individual who misses just two months’ premium payments is dropped from coverage and prohibited from reenrolling for several months. Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts and Vermont instituted or increased premiums for children in SCHIP or Medicaid. Minnesota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont and Wisconsin increased premiums for adults or families. After Oregon increased premiums in its Medicaid program, enrollment fell by 40,000 people or more than one-third. After Maryland imposed premiums on SCHIP children with incomes between 185 and 200 percent of the poverty line, about half of the children in this income range — 3,000 — were disenrolled.

- Enrollment Freezes . Six states have frozen or capped enrollment for children on SCHIP (Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Montana and Utah). In addition, Tennessee has imposed a freeze on enrollment of children in its Medicaid waiver program. When such freezes or caps are imposed, eligible children who apply are barred from enrolling. In some of these states, they are not even permitted to place their names on a waiting list. Florida currently has a waiting list of about 71,000 children who are eligible but uninsured. Colorado’s freeze will result in 15,600 fewer children being insured by the end of this year. Colorado also has frozen enrollment of pregnant women with incomes between 133 percent of the poverty line and 185 percent. New Jersey has frozen enrollment of low-income parents whose incomes fall between the limits for welfare (about 25 to 37 percent of the poverty line) and 200 percent of the poverty line.

Cuts like these will cause the number of Americans without health insurance coverage to rise. This loss in public insurance coverage comes on top of the loss of private health insurance coverage that has occurred across the nation in recent years.

The depth of the Medicaid cuts could have been still greater. The $20 billion in fiscal relief for states that Congress passed earlier this year temporarily increased the federal Medicaid matching rate (so that states pay a smaller share of total Medicaid costs) and provided additional grants to states. This fiscal relief helped numerous states avert or reverse deeper Medicaid or SCHIP cutbacks. For example, Ohio and New Jersey each used fiscal relief funds to avert planned cutbacks of Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults that would have reduced caseloads by about 60,000 in each state. Montana opened SCHIP enrollment to 1,300 eligible children who were on a waiting list. In contrast to the large number of Medicaid cutbacks that states approved earlier in the year, few states took steps to cut Medicaid caseloads after the fiscal relief funds became available. (Note: A number of states did not use the fiscal relief in this manner, in part because the federal legislation was not enacted until after a majority of state legislatures had completed action on their annual state budgets. In some states, the fiscal relief funds may still be available to help support health insurance programs and to reverse cutbacks already enacted or to avert future reductions.)

The temporary increase in federal Medicaid matching rates is currently scheduled to expire on July 1, 2004, after which states will once again have to pay a larger share of total program costs. This will intensify pressures on state budgets for state fiscal year 2005, which begins on July 1 in most states. States are projected to face deficits of $40 billion to $50 billion in the upcoming fiscal year, despite the recent uptick in the economy. As a result, there are likely to be proposals to cut Medicaid or SCHIP further in many states in the coming year. For example, newly-elected Governor Schwarzenegger of California already has proposed to freeze enrollment in SCHIP and other health programs, beginning on January 1, 2004; these proposals would lead an estimated 114,000 children and 78,000 immigrants who are eligible for health insurance to fail to receive it next year.

In addition, problems with federal SCHIP funding policies will cause about nine states to exhaust their federal SCHIP funds in fiscal year 2005. These states will be under pressure to reduce the number of children insured by SCHIP. In 2006 and 2007, a larger number of states are expected to encounter this problem. Finally, proposals to cap federal funding for Medicaid, such as the block grant proposal that the Bush Administration offered earlier this year, could increase states’ budget difficulties and ultimately could lead to further reductions in the number of people whom Medicaid covers.

Unless the federal and state governments take steps to shore up the health insurance programs, there are likely to be further cuts that will further increase the ranks of the uninsured and place greater pressure on the health care safety net.

Medicaid, SCHIP and Public Health Insurance Enrollment Cutbacks

Because of record state budget deficits, states have implemented substantial cuts in their Medicaid programs. Recent reports have shown the depth and variety of the budget cuts that states have approved to reduce costs in their Medicaid programs in 2003 and 2004. [1] State policies have restricted eligibility or enrollment in the program, reduced the scope of benefits, increased cost-sharing by beneficiaries, taken steps to contain prescription drug costs and reduced or frozen health care provider payments.

The most serious cutbacks are those that cause low-income people to lose health insurance coverage. Earlier this year, we presented data aboutproposals for Medicaid, SCHIP or other health cutbacks being considered in 22 states. [2] This new analysis provides information about the size of approved enrollment cutbacks in Medicaid, SCHIP and other state-funded health insurance program, based on actions adopted for state fiscal years 2003 and 2004, with information on all 50 states and the District of Columbia. [3] The analysis encompasses both policies enacted by state legislatures and administrative policies adopted by state agencies. In some states, policies have been blocked or delayed because of legal challenges, court-ordered injunctions or settlements. Our estimates are adjusted to account for the current status of injunctions or settlements, to the best of our knowledge.[4]

Our estimates of the size of enrollment reductions are based primarily on official state sources, such as budget estimates made when the legislation was being considered or state data concerning caseload reductions that have occurred since the changes were adopted. In some cases, we also use estimates from independent analysts. The state-specific policy changes and estimates of the reductions are listed in the Appendix.

Such estimates have inherent limitations. It can be difficult to predict the impact of new policies. In some states, there has not been enough post-implementation experience to know if the state budget projections are reliable. In addition, states are not consistent with each other in how they estimate caseload changes. To compensate, in some cases we provide a range of estimates that includes the state’s budget estimate as well as a more conservative estimate of the projected impact.

In some cases, we use data about enrollment reductions that have occurred since a policy was implemented. These data are likely to underestimate the policies’ impacts, since they account only for actual reductions in enrollment from one period in time to another and do not take account of the caseload growth that likely would have occurred in the absence of policy changes, especially a period during which the job market continues to be weak. [5] Our estimates are also limited by circumstances in which no estimates are available from a state concerning the number of people who will lose coverage because of new policies; we have no estimates in those states.

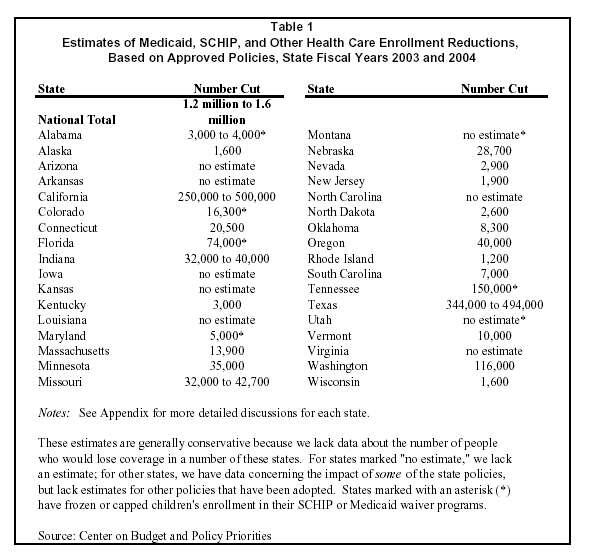

Table 1 summarizes the estimates of the magnitude of enrollment cutbacks in each state. The Appendix provides more detailed information about the policies and estimates in each state. In total, we estimate that states have adopted policies that will lower enrollment in Medicaid, SCHIP and state-funded health programs (like MinnesotaCare or Washington’s Basic Health program) by approximately1.2 million to 1.6 million people [6] Given the number of states for which no estimate of the number being cut is available, our estimate of 1.2 to 1.6 million losing coverage should be considered conservative.

States have adopted many different types of policies to reduce enrollment:

- Direct Eligibility Restrictions.[7] Some states reduced the eligibility limits for the programs. For example, Connecticut eliminated Medicaid coverage for parents with incomes between 100 and 150 percent of the poverty line. Missouri lowered the Medicaid income limit for parents from 100 percent to 77 percent of the poverty line. Texas lowered the income eligibility limit for pregnant women in Medicaid from 185 percent to 158 percent of the poverty line. Alaska reduced the income eligibility limit for children in SCHIP from 200 percent of the poverty line to 175 percent and froze the limits at 175 percent the 2003 poverty line. Texas, Oklahoma and Oregon eliminated their “medically needy” programs, which serve people who have gross incomes above the regular Medicaid income limit but whose high medical expenses leave them with disposable income below the regular income limit. Nebraska and North Carolina reduced health coverage for people who left welfare by scaling back their transitional Medicaid benefits from 24 months to 12 months.

- Increased Enrollment Barriers. Many states have adopted policies that make it more difficult for applicants to enroll in Medicaid or SCHIP or harder to stay enrolled once admitted. In many cases, these changes cancelled policies that had been adopted within the past few years to simplify enrollment and to make the programs more consumer-friendly. For example, several states (Arizona, Connecticut, Indiana, Nebraska and Texas) rescinded policies that provide 12 months of continuous eligibility for children and instead require reapplications or reviews at least every six months. California, Minnesota and Washington made similar changes affecting the enrollment of families or parents. (See box.)

- Increased Monthly Premiums . Several states instituted or increased monthly premiums that participants in SCHIP, state-funded health insurance programs or certain categories of Medicaid must pay. When premiums are imposed or increased, participation falls. [8] Requiring low-income people to pay a monthly fee causes some people currently on the program to drop off and discourages some new applicants from joining. In many states, an individual who misses even two months’ premiums will be dropped from coverage and prohibited from reenrolling for several months. After Oregon increased premiums in its Medicaid program, enrollment fell by more than one-third (40,000 people). After Maryland imposed premiums for SCHIP children with incomes between 185 percent of the poverty line and 200 percent, about half (3,000) of the children in this income range were disenrolled.

Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Vermont and Washington [9] are increasing premiums for children in SCHIP or Medicaid. Minnesota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont and Wisconsin have increased premiums for adults or families.

- Enrollment Freezes . Six states have frozen or capped enrollment in SCHIP and are not allowing new applicants to enroll (Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Montana and Utah; Tennessee also has a freeze on enrollment of children into its Medicaid waiver program, which is essentially the same as an SCHIP freeze).[10] As of mid-November, Florida had a waiting list of about 71,000 children eligible for SCHIP who are not covered. About 44,000 of these children are on the waiting list due to a general SCHIP freeze adopted in July 2003. The rest are immigrant and other children who are on a related waiting list due to an earlier, more targeted enrollment freeze. In some other states, waiting lists are not kept and eligible children are simply turned away and told to reapply when enrollment is reopened. Colorado, for example, does not maintain a waiting list and projects that 15,600 fewer children will be served by the end of the year. In some cases, enrollment caps are being used to reduce caseloads below the prior levels of enrollment. Alabama expects to lower enrollment by 3,000 to 4,000 below the caseload levels that existed before the freeze was imposed.

Enrollment Barriers Are Cuts

Most states made major strides in the past several years in streamlining Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment of children or families and helping those already enrolled to maintain coverage, such as by making it simpler to enroll by mail or phone, simplifying applications, reducing paperwork requirements or offering 12 months of continuous eligibility.a States took these steps to improve access for low-income working families.

In addition, research showed that large numbers of eligible low-income children were going uninsured because their families lacked awareness of the programs or found it too complicated to enroll. Simplification efforts have been shown to help address this problem. Such efforts have the virtue of increasing the enrollment of eligible people without significant increases in the participation of ineligible people. Studies in Maryland, Michigan and Ohio have shown that reducing paperwork requirements related to verification did not result in high error rates.b

Once enrolled, many families encounter challenges to maintaining enrollment. A survey conducted by the National Academy of State Health Policy found that almost half the families whose children’s enrollment had lapsed said it was too difficult to obtain the documents required to complete the renewal process.c Loss of coverage occurred even though families were eligible and wanted to remain enrolled. For example, making families submit paperwork on a more frequent basis reduces the number of eligible children who are enrolled, promotes “churning” in the program, increases administrative burdens, and disrupts the continuity of health care. These barriers can be eased by enrolling children and families for longer periods (such as 12-month periods), requiring less frequent redeterminations, and reducing paperwork burdens.

Due to budget pressures, however, some states have begun to rescind their simplification efforts and to reinstitute policies that impose barriers to enrollment by eligible children and families. Policy officials sometimes perceive that policies that create enrollment barriers are less harsh than direct eligibility cuts. To the extent that the barriers such policies create cause eligible people to lose health insurance, the policies are equally harmful.

a Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, “Preserving Recent Progress on Health Coverage for Children and Families: New Tensions Emerge,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, July 2003.

b Studies cited in ibid.

c T. Riley, C. Pernice, M. Perry and S. Kannel. Why Eligible Children Lose or Leave SCHIP, Portland, ME: National Academy of State Health Policy, Feb. 2002.

Some states have also frozen or capped enrollment for certain categories of adults in SCHIP or state-funded health insurance programs. Colorado has frozen enrollment of pregnant women with incomes between 133 percent and 185 percent of the poverty line. New Jersey has frozen enrollment of low-income parents in NJ FamilyCare and no longer admits parents whose incomes are between the welfare income limits (25 to 37 percent of the poverty line) and 200 percent of the poverty line. Washington has reduced the enrollment cap in its Basic Health program and plans to lower caseloads by about 36,000.[11]

The Wide Range of Beneficiaries Losing Coverage

The cutbacks that states adopted affect diverse types of low-income beneficiaries: children, parents, seniors, the disabled, pregnant women, childless adults and immigrants. Children. Almost half of those losing coverage — 490,000 to 650,000 people — are children in Medicaid or SCHIP. The state with the deepest cuts in children’s coverage is Texas. Many other states, including Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, and Washington, also have reduced children’s coverage. A few states have directly reduced their eligibility criteria for children (e.g., Alaska reduced income limits in SCHIP and Texas imposed an asset test in SCHIP). The bulk of the cuts are attributable to the institution or reinstitution of enrollment barriers, premium increases or enrollment caps.

One early sign of changes in children’s enrollment is the fact that SCHIP enrollment, which had been growing at double digit rates each year through 2002, slowed substantially in 2003. National enrollment of children in June 2003 was just 7 percent higher than in the year before. This is a modest increase given the rising needs for public coverage caused by the continued erosion of private health insurance for children and the still weak job market. In many states, SCHIP enrollment failed to grow or fell. [12] (Comparably recent data on Medicaid enrollment for children are not available.)

Parents. The next largest group losing coverage is low-income parents. Some states have lowered the eligibility criteria for low-income working parents. Connecticut scaled back the income eligibility limit for parents from 150 percent of the poverty line to 100 percent, ending coverage for about 19,000 adults. Missouri lowered eligibility from 100 percent of the poverty line to 77 percent and made other related changes, affecting between 32,000 and 42,700 parents. Nebraska cut eligibility for about 12,750 parents by modifying a variety of eligibility rules.

Each of these states encountered legal challenges. So far, the courts have found that families who lose eligibility when “family coverage” standards are reduced must be offered transitional Medicaid benefits that can continue coverage for up to one year. Although the courts’ affirmation of the requirement for transitional Medicaid is vital, these parents will lose Medicaid coverage when the transitional period ends.

More recently, states have sought to reduce parents’ coverage by creating enrollment barriers, such as by requiring eligibility reviews every six months or making verification requirements more cumbersome. Actions in California, Minnesota, Washington and Wisconsin exemplify this trend. These policies may cause substantial numbers of people to lose coverage because a large number of eligible parents are unable to complete the necessary paperwork.

Seniors and the Disabled. Oregon and Oklahoma terminated their “medically needy” programs, which aid low-income people whose high health care expenses cause their disposable incomes to fall below the Medicaid income limits. Florida reduced its Medicaid income eligibility limits for the aged and disabled from 90 percent of the poverty line to 88 percent, ending coverage for about 3,400 people. Washington ended a state-funded SSI supplemental benefit program, which also resulted in the loss of Medicaid coverage for about 3,000 people. Last year, Tennessee greatly modified its Medicaid waiver program, TennCare. One change had a particularly large effect on people with disabilities and others with chronic health problems. Previously, TennCare admitted “uninsurable” people — those with chronic diseases who had been rejected by private insurance companies — even if their incomes were above the poverty line, although these beneficiaries were required to pay substantial premiums for TennCare coverage. Now, the state will no longer serve uninsurable people with incomes above the poverty line and has tightened the criteria needed to be determined uninsurable. Other states have made changes in eligibility for the aged or disabled by narrowing eligibility criteria for the disabled (Massachusetts), modifying methods of computing the “spend down” amount for the medically needy (Louisiana and Missouri), and tightening policies relating to assets and the amounts that a spouse can retain (Kentucky and Wisconsin).

In addition, many of the Medicaid benefit reductions or co-payment increases that states have adopted affect the aged and disabled more severely than child or adult beneficiaries. Since seniors and those with disabilities have greater health care needs and use services more intensively, they are more heavily affected when health services are cut or made more costly to use

Pregnant Women . Texas lowered the Medicaid income eligibility limit for pregnant women from 185 percent of the poverty line to 158 percent, ending coverage for about 8,100 women each month. Colorado covers pregnant women with incomes between 133 percent and 185 percent of the poverty line in its SCHIP program; the state has frozen SCHIP enrollment so that pregnant women with incomes in this range who applied after April 2003 are not being accepted for coverage.

Childless Adults. Coverage of adults do not have children or whose children are no longer minors is particularly vulnerable when state budgets are being cut. Unless a state has a Medicaid or SCHIP waiver that allows it to cover non-disabled, non-elderly childless adults, the state costs in covering these people are not eligible for federal matching assistance no matter how poor the people being covered may be. Minnesota eliminated MinnesotaCare and general assistance medical care coverage for childless adults with incomes above 75 percent of the poverty line and reduced benefits for those with incomes below this level. Those with incomes between 75 and 175 percent of the poverty line will be permitted to “buy into” a limited insurance plan (which lacks hospital coverage), but few are expected to purchase this coverage because of its high cost and limited benefits. In total, Minnesota expects about 16,600 low-income childless adults to lose coverage. Broader cuts made in TennCare and, more recently, in Washington’s Basic Health program, also are expected to result in substantial reductions in coverage for childless adults.

Immigrants. Since the 1996 welfare law barred Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility for recent legal immigrants, coverage of immigrants has become more vulnerable, as no federal matching funds are involved. Massachusetts recently eliminated health care coverage for about 10,000 legal immigrants. New Jersey has terminated coverage of recent legal immigrant adults. Connecticut has stopped enrolling new legal immigrant applicants unless they qualify for federal matching. Long before it instituted an across-the-board enrollment cap on children in SCHIP, Florida had capped enrollment of immigrant children in SCHIP, and tens of thousands of such children have been on waiting lists since that time. In addition, Colorado approved a plan to eliminate Medicaid eligibility for about 3,500 legal immigrants who are eligible for federal matching assistance. Implementation of Colorado’s policy has been delayed, pending the outcome of a legal challenge.

Expansions. This paper focuses on Medicaid, SCHIP and related policies that result in lower enrollment. Some states, however, have managed to expand coverage or improve enrollment procedures in the past year. Noteworthy examples of states that have expanded coverage are Illinois (which continued to expand coverage for low-income parents under its Medicaid/SCHIP waiver program and expanded eligibility for children in SCHIP), Wyoming (which expanded children’s eligibility for its SCHIP program) and Missouri (which expanded Medicaid income eligibility for seniors and people with disabilities). Virginia streamlined enrollment procedures and substantially increased coverage of low-income children in Medicaid and SCHIP.

Some states also continued to simplify enrollment procedures. For example, Alabama, Georgia, Maryland, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina and Utah eliminated the requirement for face-to-face interviews when parents renew their Medicaid coverage. The scope of these expansions pales, however, in comparison to the size of the cutbacks.

Federal Fiscal Relief

In May, Congress passed and the President signed legislation that provided about $20 billion in fiscal relief for states: $10 billion through increases in the federal Medicaid matching rate (known as the FMAP or federal medical assistance percentage) for the period from April 2003 to June 2004, and $10 billion through fiscal relief grants covering fiscal years 2003 and 2004. In a large number of states, the fiscal relief funds proved critical in helping to avert more serious Medicaid cutbacks. [13]

Examples of how fiscal relief funds enabled states to avert deeper cuts include the following:

- Ohio averted a planned cutback of eligibility for parents with incomes between 80 percent and 100 percent of the poverty line, maintaining coverage for 60,000 low-income parents.

- Missouri rejected a cutback that had initially been approved by the legislature and would have eliminated eligibility for 13,000 parents with incomes between 60 and 77 percent of the poverty line.

- New Jersey did not institute a cutback in eligibility for low-income parents and childless adults. The state earlier stopped accepting new adult applicants into its NJ FamilyCare program, but maintained coverage of (or “grandfathered”) those who had already applied. The proposed cut would have ended coverage for the grandfathered adults, affecting about 60,000 people.

- Massachusetts restored coverage for the long-term unemployed, a group whose coverage had been terminated in the spring. The restored program will serve up to 36,000 adults.

- Minnesota was able to avert proposed cutbacks that would have eliminated coverage for about 30,000 additional low-income people, including significant numbers of pregnant women and parents.

- South Carolina avoided cutbacks in its SCHIP program and in Medicaid eligibility for the aged and disabled. The state had been considering lowering the income eligibility limit for seniors and the disabled from 100 percent of the poverty line to 85 percent.

- Montana used a portion of its fiscal relief funds to serve about 1,300 children who were on the waiting list for its SCHIP program.

- Alabama’s governor proposed cutting Medicaid income eligibility for seniors and disabled people in nursing homes after the state failed to pass a state tax referendum and the state was forced to adopt an austerity budget. This proposal could not be adopted because it would have violated a provision of the federal fiscal relief legislation that prevents a state from qualifying for the increased federal matching funds if the state restricts Medicaid eligibility between September 2, 2003 and June 30, 2004.

- Maine plans to use a large portion of its fiscal relief funds to help finance the first year of its innovative Dirigo Health Plan, which will expand health insurance coverage. The state hopes to cover about 31,000 low-income uninsured people in the first year of operations.

In short, federal fiscal relief stemmed the tide of Medicaid enrollment cutbacks in states that completed their budgets after the fiscal relief legislation was enacted on May 28. In comparison to the large number of states that cut Medicaid, SCHIP or other health programs earlier in 2003, relatively few states approved cutbacks for health care enrollment after fiscal relief was enacted. [14] It seems likely that fiscal relief also helped to avert cuts in states like Oregon and California, which had protracted budget debates, but we do not have information about specific cuts that these states declined to adopt as a result of the availability of fiscal relief funds. [15]

States also used the fiscal relief funds to avert cutbacks in the medical benefits covered by these insurance programs or to restore payments levels for health care providers. For example, Mississippi and Oklahoma are using the funds to avoid reducing the number of prescriptions that Medicaid beneficiaries can receive each month and to increase reimbursement levels for some health care providers, in order to enhance providers’ willingness to serve Medicaid patients. In other cases, the higher federal matching rate reduced or eliminated the risk of Medicaid budget shortfalls later in the fiscal year. For example, Wisconsin used the fiscal relief funds to plug an expected shortfall in its Medicaid budget, reducing the need for subsequent cuts.

One factor that affected state policies is the fact that a majority of state legislatures had already completed their budget deliberations for state fiscal year 2004 by the time the federal fiscal relief was enacted on May 28. [16] These states were unable to factor the availability of fiscal relief funds into their budget decisions. A few other states, like Texas, were just a few days from ending their legislative sessions by that date. Texas legislators essentially had already made their budget decisions and were unwilling to make last-minute adjustments to the cuts they were adopting.

Since a majority of states received fiscal relief after their budgets were approved, some states have held fiscal relief funds in reserve. Despite the tough budget environment that states continue to face, the National Conference of State Legislatures has found that states’ aggregate budget reserves for 2004 are higher than those for 2003, because some states have not yet used their fiscal relief funds. [17] In some cases, states still have the opportunity to use the federal fiscal relief funds to reverse health insurance cutbacks already approved and to avoid further cuts. In other states, the fiscal relief funds have been used to plug other aspects of state budget deficits, reducing the need for other budget cuts. Many state officials have expressed concern, however, that, after the increased federal Medicaid matching rates expire on June 30, 2004, states will again face serious budget pressures.

Conclusion

State budget crises have forced states to reduce Medicaid, SCHIP or other state health insurance coverage by approximately 1.2 to 1.6 million people. Close to half of those losing coverage are low-income children. States also have reduced benefits, increased co-payments and taken other actions that limit access to services for some of those who remain covered by these programs. The situation could have been worse. If federal fiscal relief had not been made available, the number of people losing coverage likely would have been substantially higher.

Furthermore, for every dollar that a state trims from its own Medicaid budget, it loses between one and four federal matching dollars. Similarly, each state dollar cut in SCHIP funding causes the loss of two to seven federal dollars. The combined reductions have consequences both for low-income beneficiaries, who lose services, and health care providers, who lose revenue.

There also are broader economic implications for states. Research shows that state and federal contributions to Medicaid generate a substantial amount of economic activity and employment in the states. One study estimated that a $100 million state investment in Medicaid expenditures generates about $340 million in economic activity in an average state and about 3,700 jobs, primarily in the health sector. [18] Kevin Concannon, the director of Iowa’s Department of Human Services, recently stated, “Medicaid brings $1.5 billion into this state. It’s a major economic contributor.” [19]

Moreover, reductions in Medicaid or SCHIP coverage spur greater demand for uncompensated health care, as uninsured low-income patients turn to safety-net hospitals and clinics to obtain basic and emergency health services. [20] In that regard, Medicaid and SCHIP cuts shift costs from the state and federal Medicaid accounts to other state and local government agencies and to non-profit and other health care providers. For example, reductions in enrollment in Oregon’s Medicaid program, which were caused by premium increases, have been followed by a sharp increase in emergency room use by uninsured patients at the state university medical center. [21]

Recent data from the Census Bureau and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that the number of uninsured Americans has been rising because of the weak job market and losses in private health insurance coverage. [22] The major factor that kept the number of uninsured Americans from increasing more than it did in the past two years was growth in Medicaid and SCHIP coverage. The percentage of low-income children who are uninsured actually declined in 2002, despite the poor economy, as a result of the growth in Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment. The cuts in Medicaid, SCHIP and other health programs that are being instituted, however, will increase the number of uninsured Americans. And progress in reducing the number of uninsured children could be partially reversed because of the cuts.

Of particular concern at the present time, states are beginning to develop budget options for further reductions in Medicaid, SCHIP and other health programs for state fiscal year 2005 or, in some cases, for the remainder of state fiscal year 2004. For example, California’s newly-elected Gov. Schwarzenegger recently proposed freezing enrollment in the state’s SCHIP program and capping funding for state-funded programs for immigrants, as well as further reducing health care provider payments, effective January 1, 2004. These cuts would lower enrollment of children by a projected 114,000 and of immigrants by about 78,000. Although the economy shows some signs of recovery in some parts of the country, state budget pressures continue to loom, because of continuing deficits in many states and because the federal fiscal relief expires next summer.

Adding to these problems, a number of states are at risk of no longer receiving adequate federal SCHIP funds to maintain their SCHIP enrollment levels. Under the current federal SCHIP funding formula, nine states —Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey and Rhode Island — will exhaust their federal SCHIP funds in 2005 and either have to cut their programs or come up with additional state funds to supplement the shortfall in federal funds. [23] The likely result is that SCHIP caseloads will fall. Moreover, the number of states that will exhaust their federal SCHIP funds will grow with each succeeding year unless steps are taken to bolster federal SCHIP funding. If no changes to federal SCHIP funding formula are made, the federal funding limits will cause SCHIP enrollment to be about 200,000 lower by 2007 than in 2003.

Finally, federal Medicaid funding could be at risk if caps are imposed on federal Medicaid funding for the states, as would be the case under the Medicaid block grant the Bush Administration proposed earlier this year. Such caps could increase states’ budget difficulties by limiting the amount of federal funding available for Medicaid in the future, in contrast to the more flexible funding structure that Medicaid now enjoys as an entitlement program.[24] Ultimately, states could find themselves in double jeopardy — limited on one hand by a shortfall in state funds due to budget deficits and constrained, on the other hand, by a cap on federal funds because of the block grant. A block grant could over time lead to deeper Medicaid cuts than those we have recently witnessed.

The most recent Census data show that more than one in four low-income Americans with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line — 27 percent — lacked health insurance coverage in 2002. Unless the federal government and states take steps to shore up resources for Medicaid and SCHIP, we are likely to see further reductions in publicly-funded health insurance coverage for low-income children, families, seniors and people with disabilities, particularly in the year ahead. This would further swell the already large number of low-income Americans who are uninsured.

Appendix . List of State Policies for 2003 and 2004

Note: The dates shown are the state fiscal years in which the policies were implemented or are scheduled to be implemented. That is, a policy approved by the legislature in spring 2003 for implementation in state fiscal year 2004 is shown as a 2004 policy. Our estimates are primarily drawn from official state estimates of the number of people losing enrollment, on data on changes in enrollment levels that have occurred after policies were implemented, or on estimates by other independent analysts.

Alabama . 2004: Children. Capped SCHIP enrollment. Plan to use attrition to reduce caseload by 3,000 to 4,000.

Alaska . 2004: Children. Reduced the SCHIP eligibility limit from 200 percent of the poverty line to 175 percent and removed the inflation adjustment in the income limit, so the level will fall below 175 percent of the poverty line in the future. Estimated reduction: 1,300 children in 2004. Pregnant women. Eliminated future inflation adjustments for the Medicaid income eligibility limit. Estimated reduction: 300 women in 2004. Aged/disabled. Removed inflation adjustments for the SSI income limit used in determining Medicaid eligibility for those in institutions. No estimate of reduction.

Arizona . 2004: Medicaid Children, Parents, SSI Aged and Disabled and Childless Adults: Eliminated 12 month certification period and required redetermination every 6 months. No estimate of reduction. Children: Have announced plans to increase premiums for children with incomes between 150 and 200 percent of the poverty line. No estimate of reduction.

Arkansas . 2003: Disabled Children. Added a monthly premium for certain disabled children in a special Medicaid waiver program who are using home and community-based care but who would otherwise be institutionalized. No estimate of reduction.

California . 2004: Parents. The state added a mid-year reporting requirement in Medicaid, so that enrolled parents must report changes in their incomes or other family information twice a year. This will cause some families to lose coverage if they are unable to submit the paperwork in time or if their family circumstances have changed slightly. Another measure imposed standards on local agencies concerning the timely redetermination of Medicaid eligibility; agencies that do not meet the standards will lose administrative funding. This is intended to expedite Medicaid disenrollment of parents whose certification periods have lapsed. When this legislation was passed, the state assumed that mid-year reporting would reduce caseloads by about 100,000 and the new performance standards would result in caseloads being reduced by about 400,000, suggesting a caseload reduction of about 500,000. However, the final impact of these changes is not clear because of uncertainties in how the legislation will be implemented by state and local agencies. To be conservative, we provide a lower-bound estimate that assumes the actual cuts are half as large as those budgeted; this indicates a Medicaid caseload reduction of 250,000 to 500,000. . Finally, the state reduced eligibility for transitional Medicaid coverage, so that those leaving welfare for work only get 12 months of Medicaid coverage, not 24 months, as they did before. (California also has continued to delay implementing a federally-approved SCHIP expansion that would extend coverage to parents with incomes between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty line; this delays coverage for about 275,000 uninsured parents. In addition, Gov. Schwarzenegger has proposed freezing enrollment for children in SCHIP beginning on January 1, 2004; this would reduce enrollment by an estimated 113,800 children next year. The new governor has also proposed freezing enrollment in state-funded health care provided to immigrants, which would affect an estimated 77,900 people. None of the three items mentioned in parentheses are included in our estimates of approved cuts.)

Colorado . 2003: Immigrants. Eliminated Medicaid coverage for legal immigrants who have been in the United States for more than five years. Estimated reduction: 3,500 people. Currently blocked under a temporary injunction. Pregnant women: Froze enrollment of pregnant women in SCHIP. This effectively reduces the income eligibility limit of pregnant women who apply from 185 percent of the poverty line (the level under SCHIP) to 133 percent of poverty (the level under Medicaid). Estimate of reduction: 700. 2004: Children. Capped enrollment for SCHIP children. Estimate of reduction: 15,600.

Connecticut . 2003: Children. Eliminated 12-month Medicaid continuous eligibility. No estimate of reduction. Parents: Reduced Medicaid income limit from 150 percent of the poverty line to 100 percent. Estimate of reduction: 19,000. There is a temporary injunction to maintain coverage and to assure provision of transitional Medicaid benefits, but all of these individuals will lose coverage when their transitional benefits expire. 2004: Children. Eliminated “presumptive eligibility,” a policy used to expedite enrollment of children who apply for Medicaid when they get care at clinics or hospitals. Estimate of reduction: 1,500. Immigrants. Froze enrollment of legal immigrants not eligible for coverage financed in part with federal funds because they are immigrants. No estimate of reduction. (Children and Parents: The legislature has authorized imposing premiums on children and parents enrolled in Medicaid. An initial proposal for premium increases made by Gov. Rowland would lead to the disenrollment of about 86,000 people, two-thirds of them children, but a waiver must be submitted to HHS and approved before this policy can be implemented. Because of the early nature of this policy, we do not count it as an approved policy, even though it has legislative authorization.

Florida . 2003: Aged and Disabled. Reduced income eligibility limit from 90 percent of the poverty line to 88 percent. Estimate of reduction: 3,400 persons. 2004: Children. Enrollment cap in SCHIP. About 71,000 children on waiting list as of mid-November 2003, of whom 44,000 were children added to the waiting list since the general cap was imposed on July 1, 2003 and 27,000 were children who were on a similar waiting list because they were subject to an earlier cap on state-funded immigrant children, children of state employees and 19-year olds.

Indiana . 2003: Eliminated 12-month continuous eligibility for Medicaid children and shifted to 6-month renewal periods. Estimate of reduction: 32,000 to 40,000 children. 2004: Aged and Disabled. Modified method of computing “spend down” amount for the “medically needy” component of Medicaid. No estimate of reduction. Currently blocked by legal challenge.

Iowa . 2004: Disabled. Increased premiums for disabled workers who receive medical benefits under Medicaid. No estimate of reduction.

Kansas . 2003: Parents: Tightened requirements to retain transitional Medicaid. No estimate of reduction.

Kentucky . 2003: Parents. Medicaid eligibility is ended if parents do not comply with TANF work requirements. No estimate of reduction. 2004: Children. Instituted premiums for SCHIP children with incomes between 150 percent and 200 percent of the poverty line. Estimate of reduction: 3,000 children. Parents. Imposed premiums for second six months of transitional Medicaid. Aged/Disabled. For nursing home and long-term care Medicaid eligibles, lower the limits on allowable assets and reduce the income limits for a spouse. No estimate of reduction.

Louisiana . 2003: Aged and Disabled. Modified methods of accounting for “spend-down” in “medically needy” eligibility. No estimate of reduction.

Maryland . 2004: Children. Imposed monthly premiums for SCHIP children with incomes between 185 percent and 200 percent of the poverty line. Estimate of reduction: 3,000 children, about half of those in this income range who had been enrolled. One-year freeze in the enrollment of new SCHIP children in families with incomes between 200 and 300 percent of the poverty line, although children in that income range who are already enrolled are grandfathered. Estimate of reduction: 2,000 children.

Massachusetts . 2003: Childless Adults. Eliminated coverage for certain long-term unemployed workers in Medicaid waiver program. Estimate of reduction: 36,000 terminated in April 2003. The state is establishing a new insurance program for the long-term unemployed in 2004. The new program has an income limit of 100 percent of the poverty line and caps enrollment at 36,000. The net result is that a large number of adults lost coverage at least temporarily, and many probably will not regain coverage, but the net impact is difficult to estimate at this time. Other. Increased monthly premiums for individuals in certain other Medicaid expansion categories. Estimate of reduction: 4,000. 2004: Children. Increased premiums. Estimate of reduction: 900. Parents/Adults. Added new restrictions to the asset test and imposed an enrollment cap. Estimate of reduction: 1,300 due to the assets restriction. Disabled. Tightened disability criteria. Estimate of reduction: about 2,000. Immigrants. Eliminated coverage of certain state-funded immigrant adults. Estimate of reduction: 10,000.

Minnesota . 2004: Children. Reduced automatic Medicaid eligibility for newborns whose mothers were enrolled in Medicaid from 24 months to 12 months. Estimate of reductions for newborns: 4,412. Children with incomes from 150 percent of the poverty line to 170 percent were shifted from Medicaid to SCHIP. Childless Adults. Eligibility limits in state-funded MinnesotaCare or General Assistance Medical Care have been reduced. Those with incomes below 75 percent of the poverty line will receive reduced benefits and face higher cost-sharing. Those with incomes between 75 percent and 175 percent of the poverty line will lose coverage, but will be able to purchase a new insurance benefit limited to physician and outpatient benefits. Those with incomes over 175 percent of the poverty line will lose eligibility completely. Estimate of reductions for childless adults: 16, 559. Other. Miscellaneous changes that affect coverage of parents, children and immigrants. Estimate of reductions: 3,600.

Missouri . 2003: Parents/Adults . Reduced Medicaid income limit for parents from 100 percent of the poverty line to 77 percent. Eliminated coverage of non-custodial parents. Reduced the scope of transitional Medicaid coverage for those leaving welfare for work. Previously those with incomes up to 300 percent of the poverty line could get up to 24 months of coverage beyond the mandatory federal 12 months offered; now there are only 12 months of additional coverage beyond the federal minimum, and these additional months of coverage are offered only to those with incomes below the poverty line. Estimate of reduction: 32,000 to 42,700 parents. Because of a legal challenge, transitional Medicaid coverage was retained for about 17,000 parents, but these parents will lose coverage when their transitional benefits expire. (Recent Mothers: Reduced length of eligibility for extended Medicaid coverage of family planning and related services for postpartum mothers from 24 to 12 months. Estimate of reduction: 12,800 women. Since these women were not receiving full Medicaid benefits, we do not include them in our estimates of those losing coverage.)

Montana . 2003: Children: The state authorized an enrollment cap for SCHIP. In late October, the state used fiscal relief funds to authorize coverage to about 1,300 children who were on the waiting list, but reestablished the cap after that brief opening. No estimate of reduction.

Nebraska . 2003 : Children and Parents. Reduced Medicaid “earnings disregard” from 20 percent of earnings to a flat $100. Tightened methods to determine income and household composition. Reduced transitional Medicaid from 24 months to 12 months. For children, reduced 12-month continuous eligibility to 6 months. Estimate of reduction: 12,600 children and 12,750 parents. Because of an injunction, transitional benefits are being provided to the majority of people affected by these changes, but these people will lose coverage when their transitional benefits expire. 2004: Children. Ended Medicaid presumptive eligibility for children. Estimate of reduction: 340 per month. Eliminate Medicaid coverage for poor 19 and 20 year olds. Estimate of reduction: 3,400.

Nevada . 2003: Stopped disregarding unemployment insurance benefits when computing Medicaid eligibility. Estimate of reduction: 2,900.

New Jersey . 2003: Parents. Froze enrollment of parents into Medicaid/SCHIP waiver program, NJ FamilyCare, for those with incomes between the TANF income standard (between 25 and 37 percent of the poverty line) and 200 percent of the poverty line; grandfathered coverage for those who had already applied. No estimate of reduction, but the eventual reduction through attrition will be large. 2004: Adults. Terminated coverage of state-funded immigrant adults and certain grandfathered adults with higher incomes. Estimate of reduction: 1,900.

North Carolina . 2003: Aged/Disabled. Imposed transfer-of-asset penalties on persons receiving personal care services in home. Included real property held under a life estate or tenancy in common as a countable asset when determining Medicaid eligibility. No estimate of reduction. 2004: Children and Parents: Essentially reduced transitional Medicaid benefits from 24 months to 12 months. Preliminary data indicate that 51,000 children and parents will no longer have transitional Medicaid coverage, but some will still retain Medicaid coverage using another eligibility category so the net reduction in enrollment is not yet clear.

North Dakota . 2003: Parents. Restricted Medicaid eligibility for low-income working families with two parents by barring families in which a parent works more than 100 hours per month. Estimate of reduction: 2,400. Aged/Disabled. Modified disregards of certain income used in determining eligibility. Estimate of reduction: 256. 2004: Aged. Modified spousal asset limit. No estimate of reduction.

Oklahoma . 2003: Eliminated medically needy coverage in Medicaid. Estimate of reduction: 800 children, 6,500 parents, 1,000 seniors.

Oregon . 2003: Aged/Disabled. Eliminated Medically Needy Program. Narrowed eligibility for Medicaid long term care services. No estimate of reduction. Parents/Adults. Eliminated retroactive eligibility for OHP Standard (the state’s Medicaid program for adults who are not eligible under traditional Medicaid rules, including many with incomes below the poverty line) effective March 1, 2003. Required OHP Standard applicants to be uninsured for 6 months before being eligible. Instituted and increased premiums in OHP Standard. Estimate of reduction: OHP standard enrollment down by 40,000, primarily due to premiums. 2004: Adults/Others. Repealed plans to expand OHP eligibility above 100 percent of the poverty line. No estimate of reduction.

Rhode Island . 2003: Children and Parents. Increased monthly premiums for those with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line. Estimate of reduction: 670 families completely lost coverage due to nonpayment, and 1,100 were disenrolled for 4 months due to nonpayment.

South Carolina . 2003: Parents. Imposed Medicaid gross income standard at 185 percent of the TANF standard. Estimate of reduction: 7,000. Children. Tightened paperwork requirements to renew children’s eligibility. Other. Tightened enrollment and verification procedures for certain types of applicants. No estimates of reductions.

Tennessee . 2003: All. Major changes in eligibility and enrollment policies were instituted when a new TennCare waiver was implemented in July 2002. About 600,000 beneficiaries were required to reapply for benefits; of that group, about 40,000 applied but were determined ineligible, and another 160,000 who did not complete the proper paperwork on time and were disenrolled. In March 2003, Governor Bredesen agreed to a “grace period” during which the 160,000 who had lost coverage because they did not complete the necessary paperwork on time could reapply. More recently, there was a legal settlement as a result of which the 40,000 who were determined ineligible also are being provided a grace period to reapply. As of September 2003, however, only about 15,000 of the 160,000 had reapplied under the grace period and had their coverage restored. A conservative estimate of the impact of the total enrollment loss is that at least 150,000 have lost coverage and will remain uncovered, after accounting for the grace periods. Other policy changes have also reduced access. Children. The state is only admitting children with incomes below 185 percent of the poverty line for infants, 133 percent of the poverty line for children one to five and 100 percent of the poverty line for children six and above, which are among the most restrictive entry standards for children in the nation. Other/Aged/Disabled. Before the new waiver, TennCare covered “uninsurable” people who had been rejected for private insurance coverage without regard to income, although they had to pay income-related premiums. Now, TennCare enrolls only those “uninsurable” people who have incomes below the poverty line. The state has also tightened the criteria used to determine who is uninsurable.

Texas . 2004: Children. The state added an asset test to SCHIP eligibility for children with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line, increased monthly SCHIP premiums and lowered the SCHIP enrollment period from 12 months continuous eligibility to 6 months. Estimate of reduction: about 160,000 SCHIP children. In addition, SCHIP benefits were scaled back: a child will be unable to get medical services during the first 90 days of enrollment, and the range of health services offered under SCHIP was reduced. In Medicaid, the state is postponing the implementation of a shift from 6-month to 12-month continuous eligibility for children and also is expanding the use of face-to-face verification of children’s eligibility. Compared to the baseline of expected caseload growth (due to population increases and procedural simplifications), the state assumes these changes will reduce program growth by about 330,000 children by 2005. (On the other hand, the newly budgeted caseload levels are only slightly below actual 2003 enrollment.) Estimate of reduction: Because of uncertainties in the state’s estimates for the baseline and the new legislated policy, we conservatively estimate that this will lead to a reduction of between 150,000 and 300,000 in Medicaid enrollment of children, as compared to enrollment level projected under previously enacted policies. Pregnant women. Reduced Medicaid income limit reduced from 185 percent of the poverty line to 158 percent. Estimate of reduction: 8,142 pregnant women each month. Parents. Eliminated the medically needy program for parents, which served those with incomes somewhat above the TANF eligibility level or whose medical expenses let them spend down into coverage. (Texas did not have a medically needy program for the aged.) Estimate of reduction: about 9,300 parents. Also established a policy to terminate Medicaid coverage for parents who lost TANF due to work-related sanctions. Estimate of reduction: 17,000 parents. In addition, the state plans to disenroll Medicaid parents who lose TANF due to non-work related sanctions (e.g., children do not have proper school attendance, family fails to get health check-ups); this is currently being blocked under a temporary injunction. If this policy is implemented, another 2,200 parents would lose coverage.

Utah . 2004: Children. CHIP enrollment currently closed due to enrollment cap. No estimate of reduction.

Vermont . 2004: Parents/Adults . Ended 6-month guaranteed eligibility for certain Medicaid managed care enrollees. No estimate of reduction. Adults. Plan to replace co-payments with premiums for the certain categories of adults as of January 1, 2004. Estimate of reduction: 10,000 will lose medical benefits due to premiums. Children and working disabled. Selected premium increases for this population also. Estimate of impact: 300 children and a small number of disabled. Aged. Increased premiums for those receiving prescription drugs under waiver program. Estimate of reduction: 4,000 seniors lose drug coverage. (The 4,000 are not included in our estimates of cuts, since these individuals only get prescription drugs, not full insurance coverage.)

Virginia . 2004: Parents/Adults. Eliminated transitional Medicaid for welfare participants leaving welfare for reasons other than increased earnings or child support (the state’s welfare waiver expired). No estimate of reduction. Other. Froze medically needy income limits for one year. No estimate of reduction.

Washington . 2003: Parents/Adults. Imposed premiums on adults in second six months of transitional Medicaid benefits. No estimate of reduction. Aged and Disabled. Cut state SSI supplement, which caused a loss of Medicaid coverage. Estimate of reduction: 2,000. Immigrants. Eliminated eligibility for state-funded Medicaid services for recent legal immigrants. Estimate of reduction: 29,000. 2004: Parents and Children: Ended 12-month Medicaid continuous eligibility and now requires six-month reviews. Other verification efforts added. Estimate of reduction: 25,000. Children. The state enacted legislation to increase Medicaid and SCHIP premiums for children with incomes greater than the poverty line. Pending federal approval of a federal waiver required to allow the state to implement the legislation, the state has announced it will implement this policy in February 2004. Estimate of reduction: 24,000. (Gov. Locke has just proposed eliminating the planned premiums for some children and reducing them for others. If this is approved by the legislature, substantially fewer children would lose coverage due to premiums.) Adults. Basic Health program caseload caps revised down and premiums increased. Estimate of reduction: 36,000.

Wisconsin . 2004: Parents. Required verification of health insurance and wages for employed BadgerCare applicants. Increase premiums for those with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line. Estimate of reduction: 1,200 due to verification efforts and 439 due to increased premiums. Aged. Revised policy for counting the value of annuities as assets in determining eligibility and will count the value based on the market value of the annuities. Tightened policies related to transfers to community spouse. Increased annual enrollment fee for SeniorCare from $20 to $30. No estimate of reduction.

End Notes

[1] Vernon Smith, et al., “States Respond to Fiscal Pressure: State Medicaid Spending Growth and Cost Containment in Fiscal Years 2003 and 2004,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Sept. 2003.

[2] Melanie Nathanson and Leighton Ku, “ Proposed State Medicaid Cuts Would Jeopardize Health Insurance Coverage for 1.7 Million People: An Update ,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised March 21, 2003.

[3] In addition to communications with dozens of state officials and experts in non-profit organizations around the country, we used information from the report of Vernon Smith and his associates, op cit., and we acknowledge the help of Victoria Wachino of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

[4] If there is a temporary injunction blocking a cut, we do not tabulate that cut, even though the lawsuit may eventually be resolved in favor of the state and the cut may be instituted. If a lawsuit has been filed but has not resulted in an injunction, we count the cut. If there is a settlement, we include an estimate of its impact.

[5] For example, if the number of enrollees was 100,000 before a policy was adopted and 80,000 several months later, our approach estimates the caseload reduction at 20,000. If, in reality, caseloads would have grown an additional 10,000 if the policy had not been adopted, the true impact of the policy would be a 30,000-person reduction.

[6] This does not mean that Medicaid enrollment will be 1.2 to 1.6 million lower in 2004 than in 2003. Because of the weak economy, elevated unemployment, erosion of private insurance and population growth, “baseline” enrollment in these programs would grow in the absence of policy changes. A better interpretation of our estimates is that Medicaid, SCHIP, and other health program caseload levels will be about 1.2 to 1.6 million lower than they would have been if the policies had not been adopted.

[7] The federal fiscal relief legislation enacted by Congress in May 2003 provided fiscal relief by temporarily increasing the federal Medicaid matching rate. The legislation also provided that states that directly restricted eligibility in Medicaid during the period September 2, 2003 through June 30, 2004 would not receive the increased Medicaid matching rate. This policy has helped forestall additional eligibility reductions.

[8] Leighton Ku, “Charging the Poor More for Health Care: Cost-sharing in Medicaid,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 7, 2003.

[9] On December 18, Gov. Locke of Washington proposed eliminating the planned premiums for some children and reducing them for other children. If this proposal is approved by the legislature, the number of children losing coverage in Washington would be substantially smaller.

[10] Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, “ Out in the Cold: Enrollment Freezes in Six States’ State Children’s Health Insurance Programs Withhold Coverage from Eligible Children ,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Dec. 10, 2003.

[11] The pregnant women served in Colorado and the parents served in New Jersey were covered under SCHIP waivers. Washington’s Basic Health is a state-funded program that serves people not eligible for Medicaid.

[12] Vernon Smith and David Rousseau, “SCHIP Program Enrollment: June 2003 Update.” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, December 2003.

[13] Vernon Smith, op cit. included the following comments from state Medicaid officials: “The federal relief has allowed us to step back from the brink”; “The eligibility cut has been prevented by the new FMAP”; “FMAP was a godsend to us.”

[14] The states that cut eligibility or enrollment after fiscal relief generally did so in state-funded health programs or SCHIP but not Medicaid. New Jersey and Massachusetts approved reductions in state-funded coverage of immigrants. Alabama adopted its SCHIP enrollment cap after the governor’s tax referendum failed and the state had to adopt an austerity budget. Connecticut and Wisconsin approved changes in Medicaid enrollment policies — as distinguished from Medicaid eligibility criteria — that lead to modest enrollment reductions.

[15] The California legislature reduced Medicaid enrollment before fiscal relief was enacted.

[16] Twenty-four states had already ended their regular legislative sessions by May 28 and a few others had completed their budgets by that date.

[17] Corinna Eckl, National Conference of State Legislatures, presentation at National Health Policy Forum, September 2003.

[18] Families USA, “Medicaid: Good Medicine for State Economies,” Jan. 2003. There have also been at least twelve state-specific studies conducted by economists and other researchers that produced similar findings.

[19] Clark Kauffmann, “Human Services Budget Envisions Cuts for Ill, Aged,” Des Moines Register, Nov. 20, 2003.

[20] Lynn Blewett, "Demonstrating the Link between Uncompensated Care and Public Program Participation," presented at National Academy of State Health Policy conference, Portland, OR, Aug. 5, 2003. Forthcoming in Medical Care Research and Review.

[21] David Steves, “40,000 Poor Lose Coverage: Since Requiring Premiums, State Has Cut a Third of One Program’s users,” Eugene Register Guard, October 26, 2003.

[22] Leighton Ku, “ CDC Data Show Medicaid and SCHIP Played a Critical Counter-cyclical Role in Strengthening Health Insurance Coverage During the Economic Downturn ,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised Oct. 8, 2003.

[23] Our analyses are based on the Center’s SCHIP expenditure model, which is adapted from the model used by the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and is updated to include more recent program trends and legislation.

[24] Cindy Mann, Melanie Nathanson and Edwin Park, “ Administration’s Medicaid Block Grant Proposal Would Shift Fiscal Risks to States,” Georgetown University and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised April 22, 2003.

More from the Authors