- Home

- Introduction To The Supplemental Securit...

Introduction to the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Program

What Is Supplemental Security Income?

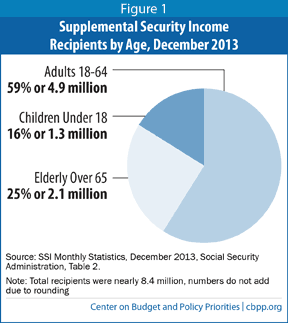

The federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program provides monthly cash assistance to people who are disabled, blind, or elderly and have little income and few assets. In December 2013, nearly 8.4 million people collected SSI benefits (see Figure 1).[1] For nearly three-fifths of recipients, SSI represents their only source of income.[2]

Although run by the same agency, SSI is distinct from the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) programs commonly known as Social Security. Nevertheless, the two programs often overlap. Many SSI recipients have worked long enough to collect Social Security but their Social Security benefit is low enough that they also qualify for SSI. Nearly one-third of adult SSI recipients under age 65, and almost three-fifths of recipients over 65, also get Social Security.

Social Insurance Versus Means-Tested Programs

An important difference between Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security is that the former is a means-tested program, while the latter is a social insurance program:

Means-tested programs are available only to persons with very few resources in the form of income or assets. Typically, recipients must also meet additional criteria; in the case of SSI, they must also be elderly, blind, or disabled. The Social Security Administration describes SSI as “assistance of last resort.” While many SSI recipients also collect Social Security, a work history is not required for SSI. Means-tested programs such as SSI have generally had difficulty in achieving high rates of participation among those eligible.

Social insurance programs protect workers and their families against common risks to their economic security, such as the loss of earnings and the cost of health care. To share these risks as widely as possible, social insurance programs aim to be universal in their coverage. Social Security is the largest U.S. social insurance program. Almost all employment is covered by the program, and benefits reflect the amount of earnings on which a worker has made payroll tax contributions. Anyone who is covered under Social Security can collect Social Security benefits once he or she works enough years and reaches age 62 or becomes disabled. While Social Security benefits vary from person to person, everyone with a work history (or the qualified dependents and survivors of such workers) is eligible to collect from the program. Virtually every eligible person claims his or her benefit.

Who Qualifies for SSI, and What Benefits Do They Receive?

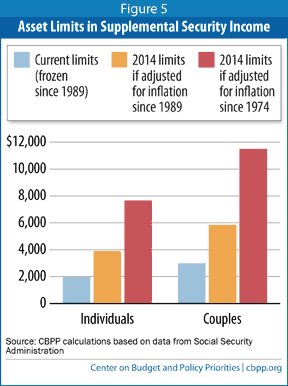

To qualify for SSI, applicants must be aged or disabled and have little or no income and few assets (no more than $2,000 in assets for an individual or $3,000 for a couple, in most cases).

In 2014, the basic monthly SSI benefit is $721 for an individual and $1,082 for a couple.[4] Beneficiaries who live in another person’s household and receive in-kind maintenance and support qualify for one-third less than this amount, while beneficiaries who receive long-term care in a Medicaid-funded institution qualify for $30 per month. Many states supplement the federal SSI benefit, though state budget cuts are crimping those additional payments.

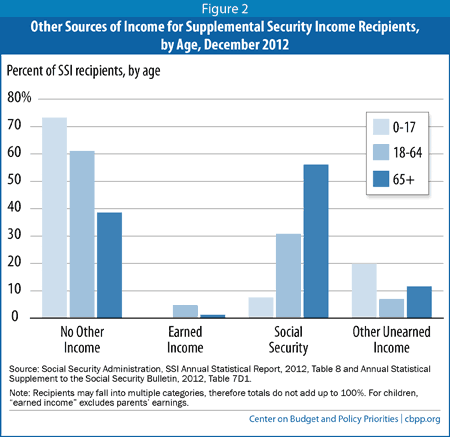

Those benefits, though, are reduced when recipients have other income. In determining a person’s SSI eligibility and benefit levels, SSA exempts the first $20 per month of unearned income, such as Social Security benefits, pensions, interest income, or child support (this is known as the “general income exclusion”) as well as the first $65 per month of earnings (this is known as the “earned income exclusion”).[5] Above those thresholds, each dollar of unearned income reduces SSI benefits by a dollar, while each dollar of earned income reduces SSI benefits by just 50 cents — a provision that is meant to encourage work. SSA also exempts certain work-related expenses when reducing SSI benefits because of earnings. While a small percentage of SSI recipients have some earnings and a somewhat greater percentage have unearned income, most recipients have no other source of income (see Figure 2).

Although the basic monthly SSI benefit for an individual was $710 in 2013, other sources of income reduced the average monthly benefit to only $529 in December 2013.[6]

SSI recipients may also get noncash forms of assistance. In most states, anyone who receives SSI benefits is automatically eligible for Medicaid. About half of SSI recipients also receive food stamps.[7] About one-fourth of recipients live in public housing or receive other housing assistance, such as vouchers.[8]

Individuals may apply for SSI by phone or in person at one of SSA’s field offices. SSA will verify the applicant’s identity, age, work history, and financial qualifications. In the case of disability applications, state agencies called Disability Determination Services (DDSs) screen the medical and related evidence to judge whether the applicant meets the criteria set out in law — basically, whether he or she suffers from a severe impairment that will last at least 12 months or result in death and that makes it impossible to engage in substantial work. (A slightly different definition applies to disabled children under age 18.) If the DDS initially denies the application, individuals have several levels of appeal and may choose to be represented by an attorney.

How Has SSI Changed Over Time?

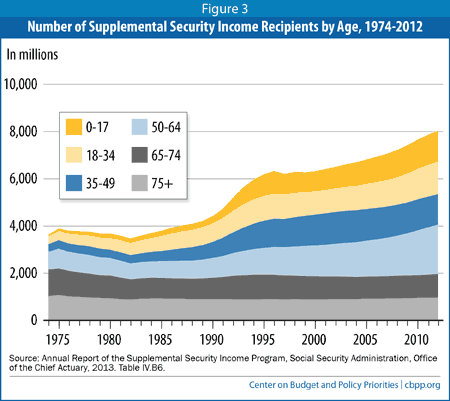

Since 1974, the number of SSI recipients has slightly more than doubled (see Figure 3). Over that time, SSI has changed from a program that mainly supplemented Social Security income for elderly adults to a broader anti-poverty program that aids the disabled of all ages. SSI is an increasingly important program for children and persons with disabilities.

A substantial number of children — 1.3 million in December 2013 — receive SSI benefits. Children with disabilities may be eligible for SSI since a child’s disability can impose additional costs on his or her caregiver. The number of children receiving SSI has gradually increased since 1974 and accelerated dramatically after a 1990 Supreme Court ruling liberalized the disability criteria for SSI children.[9] Reforms enacted in 1984 that expanded benefit eligibility for the mentally disabled (and that took several years to implement) also influenced the surge in children receiving SSI.[10] Congress tightened the SSI eligibility rules for children in the 1996 welfare-reform law, however.

Most children who receive SSI live with a single parent and receive special education; on average, SSI payments provide nearly half of their family’s total income. SSI program rules encourage parents to work; one-third of child recipients in single-parent households, and two-thirds of those in two-parent families, have a working parent.[11]

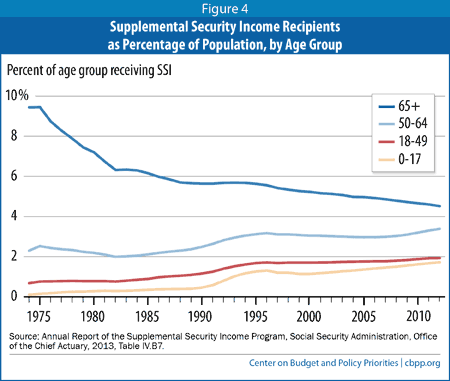

The vast majority — 86 percent — of all SSI recipients in 2012 were eligible because of a disability, and 6 in 10 disabled recipients had a mental disability.[12] The share of SSI recipients who are disabled (rather than elderly) has grown steadily since the program’s creation. Nevertheless, since the mid-1990s, SSI recipients under age 65 have essentially stabilized as a percentage of their respective age group. And the percentage of people 65 and older who receive SSI has continued to fall (see Figure 4), chiefly because of increases in Social Security payments and restrictions on eligibility for legal immigrants who arrived after 1996. Thus, even as the number of recipients continues to rise, SSI is not generally growing faster than population.[13]

How Is SSI Funded?

As an entitlement program, SSI is available to anyone who meets its eligibility requirements. Unlike Social Security (which is financed by dedicated payroll taxes), SSI is funded from general revenues. At a cost of just over $50 billion in fiscal year 2012, SSI constitutes a small portion of the federal budget — 1.4 percent of total spending that year. [14] SSI expenditures were 0.33 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2012 and are expected to decline to 0.23 percent of GDP by 2037.[15]

How Effective Is SSI?

SSI benefits are about three-fourths of the poverty line for a single person and slightly over 80 percent of poverty for a couple.[16] Thus, while SSI alone is not enough to lift someone who lives independently out of poverty, it is instrumental in reducing the number of people in extreme poverty, and it greatly lessens the burden on other family members. An SSA study found that, in 2010, the poverty rate (based on family income) of recipients would be 65 percent without counting SSI payments; the actual rate, including SSI, was 43 percent. Most families with an SSI recipient remained below 150 percent of the poverty threshold.[17]

SSI is highly effective in reducing the aggregate poverty gap — that is, the total amount of money needed to lift families out of poverty — among SSI recipients. In 2010, SSI reduced the aggregate poverty gap by over two-thirds. [18] Still, more than two-fifths of SSI recipients live in families with incomes below the poverty threshold, even after taking their benefits into account, and many more elderly or disabled persons in need of assistance do not get any benefits.[19] The following reforms could increase benefit adequacy and improve SSI participation among eligible people.

- Raise benefit levels. Congress could consider increasing the basic SSI award to the poverty level. If SSI benefits equaled 100 percent of the poverty level, the basic SSI award for individuals would increase from $721 to $973 in 2014 and the basic SSI award for couples would increase from $1,082 to $1,311. Lawmakers could also examine how SSI benefits are adjusted from year to year. Currently, SSI benefits increase with inflation by a cost-of-living adjustment but are never adjusted to reflect real wage growth in the economy. Thus, unlike wages, SSI benefits have remained virtually unchanged in real terms for decades.[20]

- Update the asset limits. The asset limit of $2,000 for individuals and $3,000 for couples may prevent many elderly and disabled persons who are truly in need from qualifying for SSI. These asset thresholds were last updated in 1989 — the only time they have increased since SSI was created in 1972.[21] (Moreover, that increase only partially captured the effects of inflation.) If the asset limits had been indexed to inflation since 1989, they would be almost twice as high as they are today — and if they had been indexed since the program’s 1974 launch, they’d be almost four times as high (see Figure 5).[22] Furthermore, the decline of defined-benefit pension plans and the spread of defined-contribution and similar arrangements has created a pressing need to modernize the treatment of retirement savings in the SSI program. [23]

- Image

Update the limits on other income. Like the asset limit, the general income exclusion and earned income inclusion are in desperate need of adjustments for inflation. The amount of income that SSA disregards when calculating SSI benefits has not changed since 1972. Over time, this failure has increasingly eroded SSI benefits for people on Social Security or those who work.

For example, the $20 general income exclusion was intended in part to ensure that SSI recipients with a significant work history, and who therefore receive Social Security benefits, would have higher total incomes than SSI recipients who had little or no work history. Yet because the exclusion has remained frozen for four decades, the difference in combined SSI and Social Security benefits between recipients with and without significant work history has largely disappeared. Likewise, the $65 exclusion for earned income is so low that its work incentive has greatly diminished.

- Improve treatment of legal immigrants. Until 1996, poor immigrants who were legal permanent residents of the United States generally qualified for SSI on the same basis as U.S. citizens. The 1996 welfare law eliminated most noncitizens’ eligibility for SSI unless they fall into one of three main groups: lawful residents who entered the United States by August 1996; refugees and other humanitarian immigrants who entered after that date (who can receive SSI only on a temporary basis, set at seven years); and ordinary immigrants who entered after August 1996 and have earned 40 quarters of coverage under Social Security. Congress temporarily extended the seven-year limit for refugees to nine years in 2008, but this provision expired in 2010, immediately terminating benefits for several thousand poor refugees who had fled to the United States in order to escape persecution.[24]

A 2002 SSA study simulated how selected SSI program changes would affect program participation and poverty status among the elderly. SSA found that the most effective — though also the most expensive — reform was increasing the income exclusion levels, which raised participation by 20 percent and decreased the aggregate poverty gap among the elderly by 8 percent.[25]

In sum, SSI is an effective anti-poverty program that constitutes a relatively small portion of the federal budget. SSI is critical in reducing extreme poverty among the elderly and disabled. However, policymakers can take a number of steps to make SSI even more effective in helping those who are unable to support themselves because of advanced age or disability.

[5] For someone with no unearned income, the $20 and $65 exemptions are combined, so that the earned income exclusion becomes $85 per month.

[6] SSA, “SSI Monthly Statistics, December 2013.”

[7] Brad Trenkamp and Michael Wiseman, “The Food Stamp Program and Supplemental Security Income,” Social Security Bulletin, 67(4), 2007, p. 71, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v67n4/67n4p71.pdf. California pays SSI recipients an extra cash supplement in lieu of food stamps.

[8] Michelle Stegman Bailey and Jeffrey Hemmeter, Characteristics of Noninstitutionalized DI and SSI Program Participants, 2010 Update, Social Security Administration Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, Research and Statistics Note 2014-02, February 2014, Table 9, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/rsnotes/rsn2014-02.html.

[9] SSA Office of Policy, Trends in the Social Security and Supplemental Security Income Disability Programs, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/disability_trends/sect04.html.

[10] United States General Accounting Office, Social Security: Rapid Rise in Children on SSI Disability Rolls Follows New Regulations, September 1994, http://archive.gao.gov/t2pbat2/152512.pdf.

[11] , Kalman Rupp, et al., “A Profile of Children with Disabilities Receiving SSI: Highlights from the National Survey of SSI Children and Families,” Social Security Bulletin, 66(2), 2006, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v66n2/v66n2p21.pdf; Kathy Ruffing and Donna Pavetti, SSI and Children with Disabilities: Just the Facts, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 14, 2012; https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3875.

[12] SSA, SSI Annual Statistical Report 2012, Highlights 2012.

[13] SSA Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT), Annual Report of the Supplemental Security Income Program, June 2013, http://www.ssa.gov/oact/ssir/SSI13/ssi2013.pdf.

[14] The total cost of SSI in fiscal year 2012 ($50.7 billion) includes $3.6 billion for administrative costs, which are subject to annual appropriation. See The Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2014, p. 1189, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2014/assets/ssa.pdf .

[15] SSA OCACT, Annual Report, Table IV.D1.

[16] Based on Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) poverty guidelines, which differ slightly from thresholds used by the Census Bureau to determine the number of people living in poverty. See http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/index.cfm for HHS poverty guidelines. See http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/index.html for Census Bureau poverty thresholds.

[17] SSA, Characteristics, February 2014, Table 13.

[18] SSA, Characteristics, February 2014, Table 14.

[19] See Eileen P. Sweeney and Shawn Fremstad, Supplemental Security Income: Supporting People with Disabilities and the Elderly Poor, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 17, 2005,

.[20] SSI cost-of-living adjustments have tracked inflation every year since 1975; only in 1983 did the benefit adjustment exceed inflation, as policymakers enacted a small across-the-board increase as part of that year’s Social Security Amendments. Therefore, there has been only a tiny real increase in the basic SSI award since 1974. See SSA OCACT, SSI Federal Payment Amounts, http://www.ssa.gov/oact/COLA/SSIamts.html for SSI cost-of-living adjustments since 1974.

[21] Robert M. Ball, “Social Security Amendments of 1972: Summary and Legislative History,” Social Security Bulletin, March 1973, http://www.ssa.gov/history/1972amend.html.

[22] Kathy Ruffing, “Rich Man, Poor Man: Lawmakers Should Raise and Index the SSI Asset Limits,” Off the Charts Blog, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 17, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/rich-man-poor-man-lawmakers-should-raise-and-index-the-ssi-asset-limits/.

[23] Zoe Neuberger and Robert Greenstein, “Changing Medicaid and SSI Rules to Encourage Retirement Saving,” Retirement Security Project Policy Brief, September 2008,

.[24] Kathy Ruffing, Thousands of Poor Refugees Face Loss of SSI Benefits, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 15, 2010,

.[25] Paul S. Davies, et al., “Modeling SSI Financial Eligibility and Simulating the Effect of Policy Options,” Social Security Bulletin, 64(2), 2002, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v64n2/v64n2p16.pdf.

End Notes

[1] Social Security Administration, “SSI Monthly Statistics, December 2013,” http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_monthly/2013-12/index.html, Table 1.

[2] SSA, SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2012, July 2013, Highlights 2012, http://www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2012/ssi_asr12.pdf.

[3] SSA, SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2012, p. 1 .

[4] Social Security Administration, “Fact Sheet: 2014 Social Security Changes,” http://www.ssa.gov/pressoffice/factsheets/colafacts2014.pdf.