The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Department of State (DOS) have proposed radical changes in immigration rules related to “public charge” determinations.[1] The changes, currently on hold, would likely cause large numbers of individuals to be denied lawful permanent residence status or the ability to extend their stay or enter the United States, despite extensive research on the benefits of immigration to the country and immigrants’ demonstrated upward mobility.[2]

Under longstanding immigration law, certain individuals can be denied entry to the United States or permission to remain here if they are determined likely to become a public charge. For decades, a public charge has been defined as a person who primarily depends on the government for public cash assistance such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or long-term institutional care through Medicaid. Under the new rules’ reformulation of the “public charge” definition, individuals who are determined “more likely than not” to receive even modest assistance from a far broader set of benefits — including benefits that help many workers, like SNAP (formerly food stamps) and Medicaid — at any point over their lifetime could be denied entry or permission to remain as permanent residents. Immigration officials will look at many factors to determine the likelihood of benefit receipt, including whether the immigrant’s current family income is above 125 percent of the federal poverty level.

The new rules will so radically change the public charge definition that about half of all U.S.-born citizens would likely be deemed a public charge — and by implication, considered a drag on the United States — if this definition were applied to them. While the new rules do not apply to U.S. citizens, it is instructive to consider the share of U.S.-born citizens whom the rules would characterize as a public charge when considering the reasonableness of the standard.

- In a single year, 1 in 4 U.S.-born citizens receive a benefit included in the rules’ public charge definition, data for 2016 show.

- An estimated 41 to 48 percent of U.S.-born citizens received one of the benefits in the rules’ public charge definition at some point over the 20-year period from 1997 to 2017.

- If data allowed us to look at U.S.-born citizens over the course of their lifetime, we estimate that it would show that about half of them receive one of the benefits in the rules’ public charge definition at some point.

Further evidence of the breadth of the new rules’ public charge definition is the fact that 15 percent of all individuals working in the United States, regardless of citizenship status, receive one of the benefits included in the new rules in just a single year. Our economy relies on these workers.

The current, longstanding definition of public charge is far narrower. In a single year, just 5 percent of U.S.-born citizens and 1 percent of individuals working in the United States meet the current benefit-related criteria in the public charge determination.

The new rules’ public charge criteria are not only broad but will also discriminate against individuals from poorer countries regardless of their talents, because the incomes of the vast majority of people from many countries fall below the new 125 percent-of-poverty threshold included as a consideration in the public charge determination under the new rules. This criterion will also have racially disparate impacts, as people from countries with low incomes are disproportionately people of color. While immigrants seeking to rejoin family in the United States can count their family’s income towards the 125-percent test, the test will remain hard for those joining family of modest means because the arriving individual will have income on their home country’s wage scale.

The DHS and DOS public charge policies were scheduled to take effect on October 15, 2019, but five federal courts have issued preliminary injunctions stopping the DHS rule and DOS is delaying implementation until it updates its corresponding forms and the Foreign Affairs Manual, which provides guidance to its consultant and embassy staff. (DOS has not indicated that it would delay implementation as long as the DHS rule is enjoined, however.) Nonetheless, many families that include immigrants already have forgone needed services due to extensive media coverage about the Administration’s pursuit of these policy changes.[3] Additional Administration actions have added to the atmosphere of fear and confusion, such as the President’s October 4 proclamation requiring that certain people seeking to immigrate to the United States have health insurance. (This policy has also been halted by a federal court.[4])

DHS and DOS Rules Significantly Expand Definition of Public Charge

Under federal law back to the late 1800s, immigration officials can turn down people seeking to enter the United States and/or become lawful permanent residents (also known as green card holders) if officials determine that they are, or are likely to become, a “public charge.” Longstanding federal policy considers someone a public charge if they receive more than half of their income from cash assistance programs, such as TANF or SSI, or receive long-term care through Medicaid.

The new rules significantly expand the definition of public charge in two major ways.

- They broaden the list of public benefit programs considered in a public charge determination to include, food assistance through SNAP, and housing assistance under the Housing Choice Voucher, Project-Based Rental Assistance, and Public Housing programs. Medicaid receipt when someone is 21 or older is also considered, with some exceptions (such as receipt during pregnancy and immediately after childbirth).

-

Instead of looking at whether more than half of a person’s income comes (or would likely come in the future) from cash assistance tied to need, as they do now, immigration authorities will determine, using several enumerated factors, whether the person is “more likely than not at any time in the future to receive one or more public benefits” for a certain time period —even if the benefits reflect only a small share of an immigrant’s total income.

The rules’ definition of public charge does not include benefit program receipt lasting fewer than 12 months in aggregate in a 36-month period. (Under the rules, receipt of two benefits in one month would count as two months.) Thus, an immigration official should disregard projected program participation if the official believes its duration would fall below the 12-month threshold. But officials will have difficulty applying the threshold. To do so, they would need to determine: (a) which benefit programs an individual immigrant might receive in the future, which would require in-depth knowledge of program eligibility rules and predictions about the income and characteristics of an immigrant’s future household members; and (b) how long they are likely to receive that benefit, requiring still finer-toothed predictions of someone’s future circumstances.

This would be so difficult that as a practical matter, officials probably will only determine the likelihood of receiving benefits for any period of time. Thus, any projected future receipt will likely result in a person being deemed “likely to become a public charge.”

The rules’ new criteria for determining whether an individual is likely to become a public charge include an “income test,” under which having family income below 125 percent of the poverty line — currently about $31,375 for a family of four — would count against an individual as the immigration official seeks to predict their future benefit receipt. Many low-wage workers have earnings below this level and could be deemed “likely to become a public charge” under the rules, even if they receive no benefits. And many seeking admission to the United States from a poorer country will not have current earnings (in their home country) above this level, given the wage levels in that country.

The breadth of the new rules’ expansive definition of public charge becomes clear when one calculates the share of U.S.-born citizens who would be considered a public charge if the new rules’ definition were applied to them. While data limitations preclude measuring the share of U.S.-born citizens who receive one of the rules’ named benefits over their lifetime, we can look at the share receiving these benefits both in a single year (using Census data for 2017) and over a 20-year period (using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics [PSID], a longitudinal data set, for 1997-2017).

In a single year, 24 percent — nearly 1 in 4 — of U.S.-born citizens receive one of the main benefits in the new rules’ definition. In contrast, only about 5 percent of U.S.-born citizens meet the current benefit-related criteria in the public charge determination.[5]

Looking at benefit receipt at any point over a 20-year period, approximately 41 to 48 percent of U.S.-born citizens received at least one of the main benefits in the public charge definition.[6] (The lower figure does not adjust for survey respondents’ well-known tendency to underreport receipt of benefits; [7] the higher figure does.) Also, for the 1997-2017 period, the PSID only provides data on benefit receipt for most programs every other year, so the PSID dataset lacks any measure of participation in alternate years for some programs such as Medicaid. If we were able to capture more years and a higher share of people’s childhoods (when benefit receipt is higher) with data that correct for underreporting, we estimate that about half of the U.S.-born population receives one of the main benefits in the public charge definition at some point in their lives. The PSID data make this clear. They show that 51 percent of children born during 1999-2017 in non-immigrant PSID households received SNAP, TANF, SSI, or housing assistance during that time period.

The figures presented here do not reflect the impact of the new rules’ 12-months-in-36 threshold due to data limitations. However, as noted, immigration officials trying to determine whether a non-citizen is likelier than not to receive benefits at some point in the future probably cannot predict the person’s length of future benefit receipt with any precision.

Another way to examine the breadth of the new rules’ public charge definition is to apply it to all individuals working in the United States, regardless of citizenship status. If all U.S. workers were subjected to a public charge determination, a significant share would be considered a public charge under the new rules. Looking at just one year of program participation shows that 15 percent of U.S. workers participate in one of the main benefits in the new rules’ definition. In comparison, just 1 percent of U.S. workers meet the current benefit-related criteria in the public charge determination.

The reality of the current U.S. labor market is that many workers must combine earnings with government assistance to make ends meet. As Table 1 shows, a significant share of workers in all major industry groups would be defined as a public charge if the definition were applied to them, despite their important role in these industries and the economy as a whole.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Percent using benefits under current definition |

Percent using benefits under new definition |

|---|

| All workers |

1% |

15% |

| Leisure and hospitality |

1% |

25% |

| Other services (repair and maintenance, private household workers, etc.) |

1% |

20% |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting |

4% |

19% |

| Wholesale and retail trade |

1% |

18% |

| Construction |

1% |

17% |

| Transportation and utilities |

1% |

15% |

| Educational and health services |

1% |

14% |

| Professional and business |

1% |

14% |

| Manufacturing |

0% |

13% |

| Information (publishing, broadcasting, telecommunications, etc.) |

0% |

10% |

| Financial activities |

0% |

9% |

| Public administration |

0% |

8% |

| Mining |

0% |

7% |

Most immigrants who receive benefits like SNAP or Medicaid work or are married to someone who works, a sign that they are not “dependent.” Our analysis of Census data shows that 77 percent of working-age immigrants — those who are foreign-born and between ages 18 and 64 — who received one or more of the benefits listed in the rules during 2017 also worked during the year or were married to a worker. More than 60 percent of working-age immigrants receiving benefits worked year-round (that is, 50 weeks of the year or more).[8]

Over time, immigrants who receive benefits like SNAP or Medicaid typically have even higher employment rates. Longitudinal survey data collected in 1999 through 2015 from the PSID show that,[9] among adults aged 18-44 in immigrant families who received any of the benefits covered by the public charge rules at any point during those years, the large majority were also employed a majority of the time, and even more were either employed or had an employed spouse:[10]

- Some 77 percent were themselves employed in a majority of the observed years (that is, five or more of the nine years observed in our PSID sample). This finding reflects both the frequently temporary nature of program participation and the common overlap between assistance and work within any given year.

- At least 93 percent were either employed in the majority of the observed years or married to someone who was.

- At least 87 percent were either employed themselves at the time of the final interview in 2015 or married to someone who was.

The new rules create a variety of new criteria and standards for immigration officials to use when evaluating whether an individual will likely become a public charge. Particularly concerning is a new income criterion. Under this “income test,” having family income below 125 percent of the poverty line — about $31,375 for a family of four, or more than twice what full-time work at the federal minimum wage pays in the United States[11] — would not be favorable in the public charge determination.

Many U.S. workers are paid below this level and could be deemed “likely to become a public charge” under the new rules, even if they receive no public benefits. This test will likely prevent individuals with low or modest incomes from being granted status adjustment or lawful entry/re-entry to the United States.

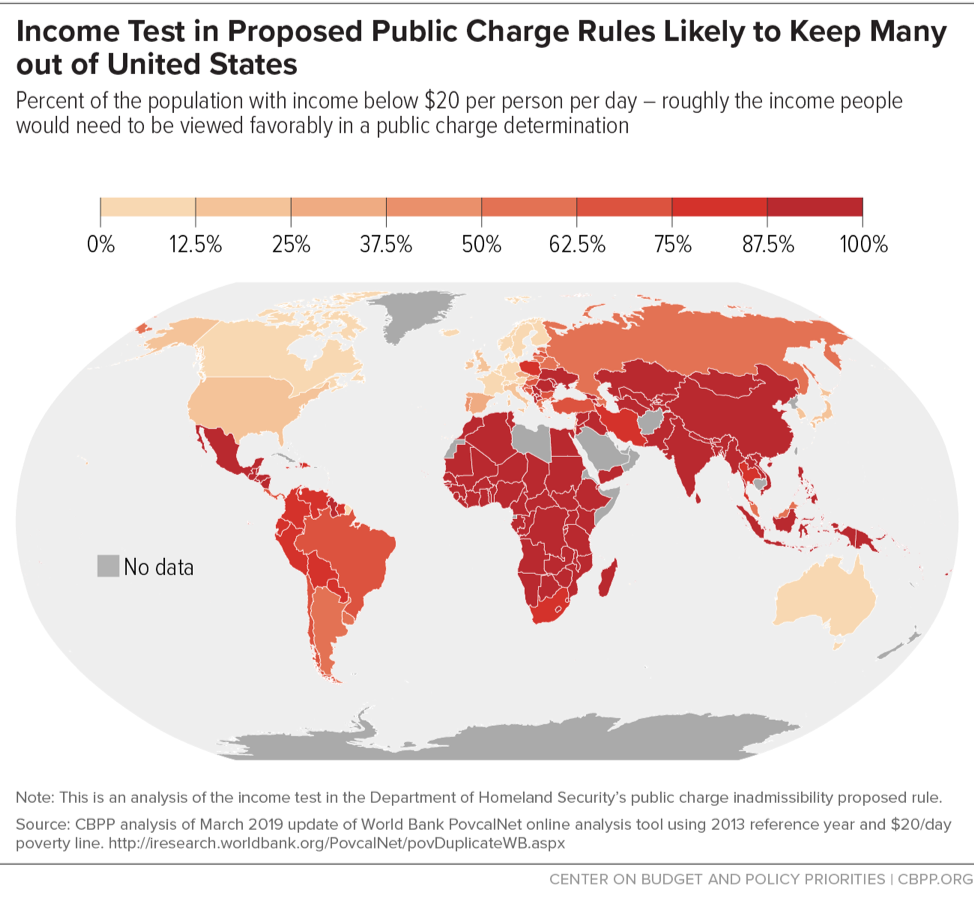

That standard also is likely out of reach for many people seeking to enter from a country where incomes generally are much lower than in the United States. The 125-percent test would disproportionately affect immigrants from poor countries (especially those whose families are not already living and working in the United States) and immigrants of color. According to a World Bank online data tool that allows users to estimate the share of the population from various countries that’s below different poverty thresholds,[12] 13 percent of the U.S. population is below the $20 per-person, per-day poverty line, which is approximately 125 percent of the U.S. poverty line. If we apply that $20-a-day threshold to the rest of the world, many individuals would fall below the threshold, including:

- 81 percent of the world population;

- 99 percent of the population of South Asia;

- 99 percent of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa; and

- 79 percent of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Of course, the figures are much different in wealthy countries. Just 14 percent of people in countries the World Bank defines as “high income” would fall below the 125-percent threshold.

The map below color-codes countries based on the percent of their populations with income below the $20 per-person, per-day poverty line. (These calculations use the March 2019 update of 2013 data because they are available for more countries. Currently, the World Bank tool includes 2015 data for a more limited number of countries.)

The above data show that applying the 125-percent threshold to potential immigrants living abroad likely would significantly affect who could be allowed to come to the United States lawfully. To be sure, many immigrants will be seeking to rejoin family in the United States who also have income that can count toward this 125-percent test. The test will remain hard, however, for those joining family of modest means, because the arriving individual will have income on their home country’s wage scale.

A country’s low wage rates say nothing about a potential immigrant’s core traits and skills or their ability to develop skills and succeed in the United States. Indeed, poor immigrants have achieved significant upward mobility for themselves and their children, helping strengthen the nation and its middle class, its industries, and its innovation sector. For example, as the data above show, few adults living in Africa earn above 125 percent of the U.S. poverty line. But, once in the United States, employed immigrant men from Africa earned an average of $63,101 in 2012 — enough to lift a family of four above 250 percent of the poverty line.[13]

By denying such a broad group of non-citizens the ability to legally enter or remain in the country, the Administration’s rules ignore not only the contributions of immigrants themselves, but also the contributions that immigrants’ children would make to the nation’s long-term strength, further weakening the economic case for the rules. Studies have long found that children of immigrants tend to attain more education, have higher earnings, and work in higher-paying occupations than their parents. “Even children of the least-educated immigrant origin groups have closed most of the education gap with the children of natives,” economist David Card observed in 2005.[14] Similarly, the National Academy of Sciences’ 2015 immigration study concluded that second-generation members of most contemporary immigrant groups (that is, children of foreign-born parents) meet or exceed the schooling level of the general population of later generations of native-born Americans.[15]

Even for immigrants without a high school education, the overwhelming majority of their children graduate from high school. In 1994-96, 36 percent of immigrants who had been in the country for five years or less lacked a high school education; two decades later, only 8 percent of the U.S.-born children of immigrants lacked a high-school education.[16] College completion rates also are higher among the children of immigrants. Some 42 percent of U.S.-born young adult children of immigrants (that is, children now in their 30s) had a four-year college degree as of March 2018 — well above the 32 percent figure for immigrants in, roughly speaking, their parents’ generation (immigrants in their 50s).[17]

The United States remains a country with one of the world’s largest and most dynamic economies. Immigrants contribute to the U.S. economy in many ways.[18] They work at high rates and make up more than a third of the workforce in some industries. Their geographic mobility helps local economies respond to worker shortages, smoothing out bumps that could otherwise weaken the economy. Immigrant workers support the aging native-born population, improving the worker- retiree ratio and bolstering the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. And the upward mobility of children born to immigrant families promises future gains not only for their families, but for the U.S. economy overall. Given the inevitable inaccuracies in immigration officials’ predictive capabilities, removing individuals or keeping them out of the country based on an extremely broad definition of “public charge” would cost the United States many needed workers, including those who care for children and seniors, build homes, start businesses, go to college, and have children who become teachers, inventors, and business leaders. Forfeiting this talent would weaken local communities and the nation as a whole.

To calculate the percent of U.S.-born citizens who have participated in a single year in programs now included in the Administration’s rules, we used the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. Our calculations include receipt of SNAP, TANF, SSI, housing assistance,[19] state and local General Assistance programs, and receipt of Medicaid for those 21 years or older. We do not count Medicaid participation for those under age 21 since the rules do not count such receipt in the definition of a public benefit.[20] We correct for underreporting of SNAP, TANF, and SSI receipt in the Census survey using baseline data from the Transfer Income Model, version 3 (TRIM3). The TRIM3 figures are for 2016, the latest year for which these corrections are available.

TRIM3 is a comprehensive microsimulation model that simulates the major governmental tax, transfer, and health programs that affect the U.S. population and can produce results at the individual, family, state, and national levels. TRIM3 was developed and is maintained at the Urban Institute under primary funding from the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (HHS/ASPE).

Our estimates conservatively understate the share of U.S.-born citizens who participate in a single year in programs included in the new definition of public charge because we do not correct for the underreporting of Medicaid. While there are a number of causes for the underreporting of the receipt of Medicaid benefits — such as memory gaps, embarrassment, or confusion about the program (e.g., Medicaid versus Medi-Cal versus Obamacare), no corrections for Medicaid underreporting are publicly available. Correcting for underreporting of Medicaid would increase the estimated share of U.S.-born citizens who participate in these programs: 74 million individuals participated in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in an average month in 2016,[21] according to HHS, but the CPS data used for this analysis only find 62 million people participated in Medicaid or CHIP in 2016.

Our estimates of benefit receipt among U.S.-born citizens over time are based on the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). Since 1968, the University of Michigan’s Institute of Social Research has followed about 5,000 families (and the families that branched off from the original survey respondents) annually.

The PSID shows that 21 percent of the U.S.-born population interviewed in 2017 recently participated in SNAP, TANF, SSI, or housing assistance at any age or participated in Medicaid at age 21 or later.[22] This estimate is lower than the single-year estimate of 24 percent cited in this report because the PSID data are not corrected for underreporting.

The PSID-based figures undoubtedly would have been higher if we could have corrected for underreporting. The CPS/TRIM-based estimate of the share of individuals who participated in one of the benefit programs in 2016 is about 1.15 times as large as the PSID-based estimate.[23] We use this adjustment factor to estimate that as many as approximately 48 percent of U.S.-born citizens participated in one of the programs listed in the rules for at least one year over the 1997-2017 period.[24]

Underreporting is just one reason that the 41-48 percent estimate described in this paper is likely lower than the actual share of U.S.-born citizens who received benefits in at least one year over this period. For the 1997-2017 period, the PSID only provides data on benefit receipt for most programs every other year. The PSID dataset thus lacks any measure of participation in alternate years for some programs such as Medicaid.

Under the new rules, immigration authorities are tasked with predicting whether someone will receive one of the benefits included in the public charge definition over the course of their lifetimes. While using PSID data for 1997-2017 is an important improvement over using a single year of data, it only captures a portion of most respondents’ lifetimes and significantly underestimates the share of U.S.-born citizens who receive a benefit at some point during their lives.