Arizona’s Medicaid program, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS), has been one of the nation’s most innovative programs since its creation in 1982, taking full advantage of the expansive flexibility Medicaid provides. It’s also highly efficient, using managed care to help provide low-cost, high-quality care to 1.9 million beneficiaries.[1] Both of the bills most recently under discussion in the Senate — the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) and a bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) without replacing it — would put AHCCCS at risk by ending the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, thereby jeopardizing coverage for nearly 400,000 Arizonans.

In addition, the BCRA would radically restructure Medicaid financing through a per capita cap. This bill as a whole would cost Arizona $7.1 billion in federal funding between federal fiscal years 2018 and 2026, according to preliminary estimates from the state Medicaid agency.[2] To compensate, Arizona would likely have to implement harmful policies that go beyond those the state imposed due to the Great Recession, such as enrollment freezes and benefit cuts.

Repealing the ACA without replacing it — or moving forward with the BCRA — would jeopardize AHCCCS’ success in providing high-quality, affordable care to low-income Arizonans. Instead of putting thousands of Arizonans at risk, Congress should use Arizona as a model as it considers bipartisan ways to strengthen both Medicaid and marketplace coverage.

Arizona was the last state to implement Medicaid, doing so in 1982 using demonstration authority under section 1115 of the Social Security Act. Using this authority, or “waiver,” Arizona was the first state to enroll most beneficiaries in managed care on a mandatory basis. Today, more than 75 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide are enrolled in managed care.[3] AHCCCS has continued to innovate and improve quality of care for the 1.9 million low-income Arizonans it now serves by:

- Implementing managed long-term care. In 1989, Arizona expanded managed care to seniors and people with disabilities by creating the Arizona Long Term Care System program, an approach that many other states are just adopting. The program provides the same medical services that non-elderly, non-disabled beneficiaries receive, as well as home- and community-based services that allow seniors and people with disabilities to stay in their homes rather than an institution. When renewing its Medicaid waiver last year, Arizona added dental coverage to the program and restored podiatry services, which it had cut in 2010.

- Expanding coverage to adults without children. Arizona has also been a leader in expanding coverage to low-income residents. Before the ACA, non-disabled adults without children were generally ineligible for Medicaid, but in 2000, Arizonans voted to expand AHCCCS (through its waiver) to adults without children with incomes at or below the federal poverty line. Unlike some other state coverage expansions for adults, Arizona didn’t limit coverage to just a few services — it provided the same benefits to this group as to other AHCCCS beneficiaries.

- Testing new payment models to improve quality of care. Arizona continues testing new models to improve quality of care for AHCCCS beneficiaries while lowering costs. AHCCCS is moving away from paying providers based on the volume of care they provide, and towards value-based care, which links provider payments to quality of care. For example, AHCCCS required health plans in its managed long-term care program to have at least 25 percent of their provider payments in 2016 in value-based models, such as incentivizing primary care or bundling payments for one episode of care (like knee surgery); this threshold rises to 35 percent in 2017.[4]

- Integrating programs and state resources. Over the past several years, Arizona has taken steps to improve coordination of care by better integrating services. For example, the state has worked with county jails to help enroll inmates transitioning back to the community before they’re released, helping to enroll over 1,000 individuals since 2014.[5] To improve coordination for AHCCCS beneficiaries also enrolled in Medicare, Arizona requires managed care plans serving this group to participate in Medicare’s managed care program, Medicare Advantage.

AHCCCS has also worked to improve the delivery of care to people with mental illness by better connecting them to providers that can treat both their physical and mental illnesses. This integration of physical and behavioral health services has improved care coordination, reduced fragmentation between providers by improving communication, and improved beneficiaries’ overall health and well-being.[6] Finally, Arizona recently completed its merger of the state’s mental health agency into AHCCCS, ensuring full integration of physical and behavioral health care management and oversight at the state level.

The Senate bill’s drastic Medicaid cuts would have harsh consequences for Arizona, including its economy. Over 400,000 Arizonans would likely lose the coverage they gained through the expansion of AHCCCS, most of whom work in jobs that pay low or moderate wages but are crucial for the state’s economy.[7] The Senate bill would also cap federal funding on a per-beneficiary basis, with funding set to grow at a rate that wouldn’t keep pace with health care costs. The resulting shortfalls would force Arizona to implement cuts in eligibility, benefits, and provider payments much greater than those instituted in 2010 and 2011, when the state faced significant budget deficits due to the Great Recession.

The Senate bill would end Medicaid’s federal-state financing partnership in which the federal government pays a fixed percentage of state Medicaid costs; Arizona’s regular matching rate is 69 percent today for most populations and services. Instead, beginning in 2020, federal funding would be capped at a set amount per beneficiary. This “per capita cap” would equal the state’s past federal Medicaid spending per beneficiary, adjusted each year at a slower rate than current projections for growth in Medicaid per beneficiary spending. That would cut federal Medicaid funding for the state, with the cuts growing each year.[8] Arizona would see a 17 percent cut in federal funding by 2026 and a 35 percent cut by 2036, the health care consulting firm Avalere estimates — figures consistent with the state’s own projection of a $7.1 billion reduction by 2026.[9]

To compensate for these cuts, states would have to raise taxes, cut other budget areas like education, or — as is far likelier — cut their Medicaid spending. But AHCCCS is already highly efficient, thanks to the numerous cost-containment measures discussed above, making eligibility, benefit, and provider rate cuts likely.[10] Funding shortfalls would be even greater if health care costs grow more quickly than anticipated due to a costly new prescription drug, or due to changing demographics such as the aging of the senior population.

The Senate bill also would effectively end the Medicaid expansion, jeopardizing coverage for nearly 400,000 Arizonans.[11] This is because starting in 2020, states would have to pay growing amounts to cover expansion enrollees as the federal share of expansion costs shrinks. For example, Arizona would have to spend $243 million more of its own funding in 2021 — an increase of 77 percent — to maintain the expansion. By 2024 the state’s added cost would rise to $773 million, meaning the expansion would cost the state three times what it would under current law. This large cost-shift would force most states to end their expansions. Moreover, Arizona is one of the nine states with a “trigger” law that ends their Medicaid expansions automatically or nearly automatically if the federal matching rate for expansion enrollees falls.[12] AHCCCS expects that this trigger would be pulled in 2022.

The Senate bill would also penalize Arizona immediately for its voter-driven decision to expand AHCCCS coverage to adults without children back in 2000. That’s because the Senate bill lowers the Medicaid match rate for expansion enrollees starting in 2018, from 91.59 percent under the ACA to 89.18 percent. The difference between what Arizona would receive under the ACA and under the Senate bill would grow each year, to over 20 percentage points by 2024. (See Table 1).

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Year |

Federal Match Under Affordable Care Act |

Federal Match

Under BCRA |

|---|

| 2017 |

89.85% |

89.85% |

| 2018 |

91.59% |

89.18% |

| 2019 |

93.00% |

88.38% |

| 2020 |

90.00% |

85.98% |

| 2021 |

90.00% |

81.98% |

| 2022 |

90.00% |

77.98% |

| 2023 |

90.00% |

73.98% |

| 2024 and beyond |

90.00% |

69.89% |

The Senate bill risks harming Arizona residents in a number of ways, including:

- Forcing AHCCCS to eliminate coverage for thousands of residents. Nearly 400,000 low-income adults covered by Arizona’s Medicaid expansion would risk losing Medicaid coverage.

- Penalizing AHCCCS for being efficient. The Senate bill doesn’t account for AHCCCS’s efficiency, including its extensive use of managed care. Arizona has lower Medicaid spending per-beneficiary than other states ($5,821, versus a national average of $7,766) and one of the lowest costs in the nation for seniors due to its expanded use of HCBS.[13] AHCCCS Director Tom Betlach notes that the bill, by locking in states at their past funding levels, would penalize Arizona relative to other states “for being a good steward of taxpayer funds.”[14] Former Governor Jan Brewer agrees: “I don’t know how you could deliver that population [AHCCCS beneficiaries] any more services better, more cheaply, than what we’ve already done here.”[15]

- Penalizing Arizona for having a large senior population. The bill’s per capita cap doesn’t address Arizona’s rapidly aging population, which would increase future per-beneficiary spending.[16] Arizona is one of five states with the highest projected growth among seniors over 85. Because each state’s cap per senior beneficiary would effectively be based on its past spending for this group, it wouldn’t take into account the significant increase in health care costs as seniors move from “young-old age” to “old-old age.” Seniors aged 85 and older incurred average Medicaid costs in 2011 that were more than 2.5 times higher than seniors aged 65 to 74, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data show.

- Weakening AHCCCS’s managed care program by cutting payments to health plans. Arizona’s current payment rates for Medicaid health plans are “actuarially sound,” meaning they are adequate to provide all covered services, promote program goals such as quality of care and improve health, and encourage providers to participate in AHCCCS. The per capita cap would undermine this system by cutting federal funding by growing amounts over time, forcing the state to cut health plan payments by growing amounts as well. Moreover, because per capita cap funding per beneficiary would be fixed, it wouldn’t allow states to adjust rates year to year or over the course of the year if care proved more expensive than anticipated. Finally, the federal funding cuts would stymie Arizona’s ongoing efforts to test new payment and service models to improve the delivery of high-quality care while reducing costs.[17]

-

Forcing AHCCCS to cut services that help keep aging Arizonans in their homes. Arizonans who retain AHCCCS coverage under the Senate bill would likely face increasingly severe benefit cuts due to the loss of federal funding from the per capita cap. Cuts could include many of the home- and community-based services that the managed long-term care program provides, which enable people with serious health problems — including children with disabilities and special health care needs — to remain in their homes by helping them with daily living activities like bathing and dressing.

Arizona has made significant progress in this area in recent years: the proportion of Arizona’s long-term care beneficiaries who stay in their own homes has risen from 49 to 68 percent since 2009, while the proportion in institutions has fallen from 31 to 14 percent.[18] The Senate bill would place these gains at risk, as HCBS are a likely target for cuts because they are optional for states and generally comprise over half of state spending on optional services.[19] This is especially true in Arizona, which spends more on HCBS as a percentage of its total Medicaid long-term spending than any other state except Minnesota, New Mexico, and Oregon.[20]

- Stopping further state innovations. For example, CMS recently approved Arizona’s proposal to use upfront federal dollars for incentive payments to providers to better coordinate physical and behavioral health care for children, adults, and people transitioned from a criminal justice facility. The Senate bill’s capped federal funding would make it harder for Arizona to move forward with innovative initiatives like this, particularly those requiring up-front federal investments.

Arizonans with Marketplace Coverage Stand to Lose, Too

The Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) would also harm Arizonans in the health insurance marketplace by raising premiums and eliminating ACA cost-sharing subsidies that reduce deductibles, copays, and coinsurance for lower-income consumers.

Many people would face a difficult choice: higher deductibles or higher premiums. The Senate bill would cut tax credits across the board by linking them to less generous, higher-deductible coverage. To avoid large increases in deductibles, people would pay higher premiums than they do today. For example, under current law a 45-year-old Arizonan with income of about $20,000 can enroll in a plan with a premium of about $900 and a deductible of less than $1,000. But under the Senate plan, she would need to choose between keeping the same premium for a plan with a deductible of $6,000 or more, or paying double the premium for a plan with a $3,600 deductible.

Older people would face especially high premiums — even for plans with dramatically higher deductibles. The BCRA would allow insurers to charge older people five times more than younger people, and would require older people to spend a larger share of their income on premiums before the premium tax credit kicks in (while lowering the share of income at which the premium credit for younger people kicks in). As a result, many older people would pay both higher deductibles and higher premiums. Consider a 60-year-old Arizonan with income of $40,000. In 2020, she would have to pay $1,500 more in premiums for a plan with a $6,000 deductible, twice as high as today’s. To lower her deductible, she’d have to pay even higher premiums.

The BCRA also would punish middle-income Arizonans, in particular, by cutting off premium tax credits at a lower income level: $44,000 instead of $50,000 in 2020. This change would hit people in higher-cost states like Arizona especially hard. For example, a 60-year-old Arizonan with income of $45,000 would lose nearly $11,000 in tax credits and would face premiums of $21,000.

The Senate bill would also seriously disrupt Arizona’s market in the near term. Arizona’s market is now stabilizing under the ACA after experiencing the largest marketplace rate increases in the nation last year as insurers corrected for previous underpricing — though the ACA’s premium subsidies largely shielded enrollees from the increases. Centene, one of the state’s two marketplace insurers, has said its financial performance in Arizona is in line with its strong financial performance in the ACA marketplaces nationwide.a Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona, the state’s other insurer, saw significant improvement in its individual market financial performance in 2016, and a company vice president recently commented, “we are starting to see some signs of stability” as “premiums in Arizona are [now] more in line with the underlying claims.”b

For consumers, these improvements in insurer financial performance should translate into lower premium increases and more insurer competition going forward. Consistent with that, the Arizona Blue Cross Blue Shield vice president predicted, “It is safe to say that rate increases will not be at the significantly high levels that you have seen the past couple of years.” But the Senate bill puts these gains at risk. CBO estimates that the bill would increase individual market premiums by 20 percent compared to current law for 2018 and would substantially reduce individual market enrollment — even before its major cuts to tax credits and cost sharing reductions would take effect in 2020.

Arizona’s experience closing large budget deficits during the last recession, when it had to make hard decisions about whom and what to cover in AHCCCS, provides clues to the likely impact of the Senate bill. It also offers lessons to other states of what’s at stake if Medicaid expansion ends and states receive increasingly inadequate federal funding under a per capita cap.

One way Arizona addressed its past shortfall was by freezing enrollment for children and adults. On December 21, 2009, Arizona stopped processing new applications for its KidsCare program, which covers children in families with incomes just above Medicaid eligibility thresholds. While children who turned in their annual renewal paperwork on time retained coverage, those who didn’t or whose family incomes rose but then fell back below KidsCare eligibility couldn’t re-enroll. As a result, enrollment in KidsCare fell by more than 60 percent, from roughly 47,000 children in December 2009 to 18,000 in July 2011.[21]

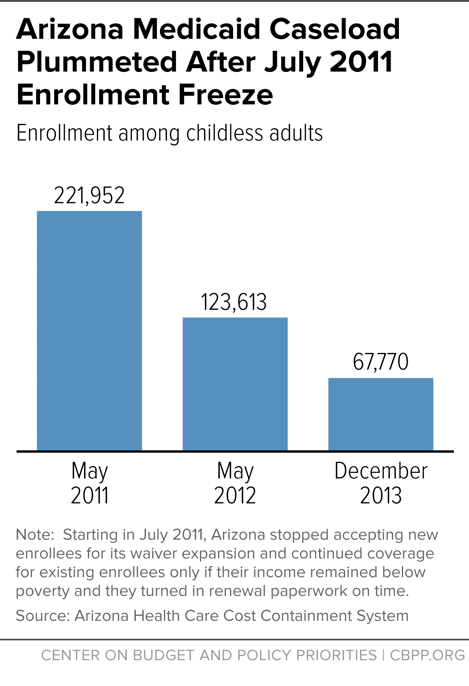

Similarly, a significant number of low-income adults lost coverage when Arizona froze enrollment for adults enrolled in its waiver expansion beginning in July 2011. CMS required Arizona to implement some safeguards, such as notifying all low-income adults about the freeze and checking whether adults about to lose coverage were eligible for other AHCCCS coverage groups (such as low-income parents or pregnant women) before disenrolling them. Despite these safeguards, enrollment fell dramatically — by nearly 45 percent within a year and by almost 70 percent by December 2013, two and a half years after the freeze took effect (see Figure 1). Arizona’s experience is consistent with a 2011 study showing fewer than half of low-income adults are continuously eligible for Medicaid over the course of a year.[22]

Arizona also cut optional Medicaid services during the last recession, including coverage for well exams, emergency dental care, and certain types of organ transplants.[23] Arizona projected that restricting transplant coverage would affect about 100 people and save $4.5 million a year. But it had devastating effects on people’s lives: a father of six died before he could receive a bone marrow transplant, a father of four with Hepatitis C lost the opportunity to get a new liver, and a self-employed plumber who had a pre-existing heart condition and couldn’t get coverage anywhere else was denied his heart transplant.[24]

Repealing the ACA would jeopardize coverage for thousands of Arizonans. AHCCCS is one of the nation’s most efficient and innovative Medicaid programs, but the BCRA doesn’t take this into account and would essentially penalize Arizona for delivering high-quality care while lowering costs. It would also penalize AHCCCS starting next year by cutting its funding for Medicaid expansion. Facing large and growing cuts in federal funding, Arizona would likely have to relive the painful cuts of its past by reducing eligibility and benefits for its AHCCCS beneficiaries.